Can't Do Your Assigned Job Due to Illness? You Might Still Be Owed Wages: Japan's Katayama Gumi Landmark

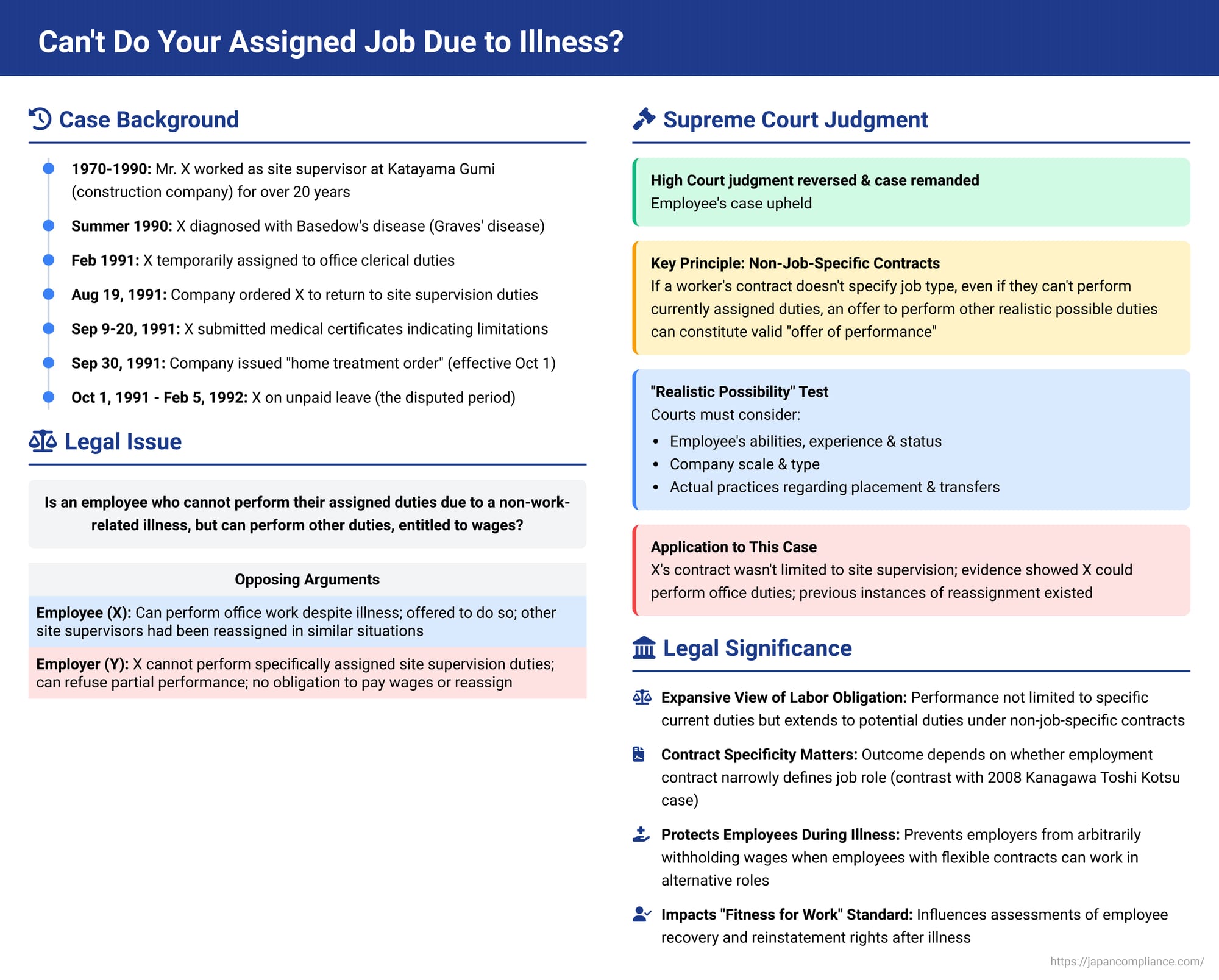

When an employee is unable to perform their assigned duties due to a non-work-related illness or injury (私傷病 - shishōbyō), it raises complex questions about their employment status and entitlement to wages. If the employee cannot work at all, the situation is often governed by sick leave policies or, in their absence, the principle of "no work, no pay." But what happens if the employee, while unable to perform their specific current tasks, is capable of performing other types of work within the company? The Supreme Court of Japan's decision in the Katayama Gumi case on April 9, 1998, provided crucial clarification on this issue, particularly for employees whose employment contracts do not restrict them to a narrowly defined job role.

The Katayama Gumi Dispute: Illness, Site Work, and a Home Treatment Order

The plaintiff, Mr. X, had been employed by Y (Katayama Gumi, a construction company) since March 1970. For over two decades, his primary role had been as a site supervisor on various construction projects. In the summer of 1990, Mr. X was diagnosed with Basedow's disease (Graves' disease), referred to in the case as "the illness."

From February 1991, while awaiting his next site assignment, X was temporarily assigned to perform office-based clerical duties, such as drafting, at Y's head office. On August 19, 1991, Y issued a work order for X to commence site supervision duties at a Tokyo metropolitan housing project ("the project site") starting the next day. Upon receiving this order, X informed Y that he was unable to perform on-site work due to his illness. His union branch, the A Union Branch (of which X was the executive committee chairman), also submitted a formal inquiry to Y, asking if the company would agree to X working under specific conditions: no on-site work, limited working hours (8 AM to 5 PM, with overtime only until 6 PM), and designated holidays (Sundays, national holidays, and bi-weekly Saturdays).

At Y's request, X submitted a doctor's certificate on September 9, 1991, which stated he was "currently under medication and requires careful follow-up observation." When Y sought further clarification, X provided a self-written statement on September 20, describing symptoms such as "severe fatigue, heart palpitations, sweating, insomnia, diarrhea, and anemia due to side effects of medication," and reiterating the need for the working conditions requested by his union.

In response, on September 30, 1991, Y issued a formal directive, "the home treatment order," instructing X to remain at home and focus on treating his illness, effective from October 1, for an indefinite period. X contended that he was still capable of performing office duties and, on October 12, submitted another doctor's note which stated, "Heavy labor should be avoided; desk work level of labor is considered appropriate." However, because this note did not explicitly state that X could perform site supervision duties, Y maintained the home treatment order.

The situation persisted until early 1992. During a court hearing for a provisional disposition filed by X seeking wage payments, X's attending physician stated that as of January 1992, X's symptoms "did not hinder work, and he could engage in sports similar to a normal person." Following this testimony, Y, on February 5, 1992, ordered X to report to the project site to perform site supervision duties, which X subsequently did.

For the period from October 1, 1991, to February 5, 1992 ("the non-working period"), Y had treated X as being on leave of absence and did not pay his wages, also reducing his year-end bonus. X sued Y to recover these unpaid wages and the deducted portion of his bonus. The lower courts, including the Tokyo High Court, ruled in favor of Y. The High Court reasoned that if an employee is partially unable to perform their duties due to a private illness, the employer can generally refuse this partial performance and is thereby relieved of the obligation to pay wages, unless principles of good faith would make it appropriate for the employer to accept the limited work the employee can offer. The High Court found no such good faith obligation in X's case and concluded that his inability to perform the assigned site supervision meant his performance of the labor obligation was effectively impossible. X appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's 1998 Landmark Ruling: Redefining "Offer of Performance"

The Supreme Court overturned the High Court's decision and remanded the case for further consideration, laying down a significant principle regarding an employee's offer of performance in cases of partial incapacity due to private illness.

The Core Principle for Non-Job-Specific Contracts:

The Court stated: "In cases where a worker has concluded a labor contract without specifying their job type or work content, even if they cannot fully provide labor for the specific duties they are currently ordered to perform, if, in light of their ability, experience, status, the scale and type of the said enterprise, and the actual conditions and difficulty of worker placement and transfers within the said enterprise, it is recognized that there is a realistic possibility of the said worker being assigned to other duties, and they are capable of providing labor for such other duties and have offered to do so, then it is appropriate to construe that they have still made an offer of performance in accordance with the true aim and purpose of the obligation (債務の本旨に従った履行の提供 - saimu no honshi ni shitagatta rikō no teikyō)."

Rationale for the Principle:

The Court reasoned that a contrary interpretation would lead to unreasonable outcomes. If two employees in the same company, under similar non-job-specific contracts, experienced similar physical limitations, their entitlement to wages could arbitrarily depend solely on their currently assigned task, irrespective of their overall capabilities, experience, or status within the company. This would be unfair.

Application to X's Case:

The Supreme Court found that:

- Although X had worked as a site supervisor for Y for over 21 years, his employment contract was not found to have limited his role exclusively to site supervision duties.

- Even if X's own description of his symptoms was somewhat exaggerated, he was demonstrably capable of performing office-based work at the time the home treatment order was issued, and he had, in fact, offered to perform such duties.

- Given these facts, the lower court could not immediately conclude that X had failed to offer performance in line with the "true aim and purpose of the obligation."

- The case needed to be re-examined to determine whether there were other duties at Y Construction to which X could have been realistically assigned, taking into account his abilities, experience, status, Y's company size and type, and Y's actual practices regarding employee placement and transfers. The Supreme Court specifically noted X's assertion that there were past instances where site supervisors unable to perform site duties due to illness or injury had been reassigned to other departments, a point the lower court had not adequately investigated.

"Realistic Possibility of Assignment" – A Key Condition

The Supreme Court's ruling does not grant an employee an automatic right to be assigned any other work they claim they can do. The principle is qualified by the crucial condition of a "realistic possibility" of assignment to other suitable tasks. This involves a multi-faceted assessment by the court, considering:

- The employee's specific abilities, experience, and status within the company.

- The employer's size, type of business (industry).

- The employer's actual, established practices regarding personnel placement and internal transfers, including the ease or difficulty of making such reassignments.

If, after considering these factors, it is determined that no such "realistic possibility" of assignment to alternative duties existed, then an employee's offer to perform such non-assignable tasks might not be considered a valid offer of performance under their contract. The Supreme Court remanded the case for the lower court to make these specific determinations.

It's noteworthy that upon remand, the Tokyo High Court found in favor of X. It determined that reassigning site supervisors to office-based roles was not unheard of at Y Construction, citing several past instances where employees unable to continue site work due to illness or injury were moved to different roles. The court concluded that suitable office work existed which X, with his long experience, could have performed, and thus there was a realistic possibility of reassigning him. Y's subsequent appeal of this remand decision to the Supreme Court was not accepted.

Implications for Employers and Employees

The Katayama Gumi decision has significant implications:

- For Employers (with non-job-specific employment contracts):

- An employer cannot automatically assume there is no obligation to pay wages if an employee, due to private illness, cannot perform their currently assigned specific tasks.

- If the employee's contract doesn't limit their role to that specific task, the employer must consider whether the employee is capable of performing other work to which they could realistically be assigned within the company.

- If the employee makes a credible offer to perform such alternative suitable work, and the employer refuses this offer without legitimate justification (e.g., by insisting on the original task or maintaining a home treatment order when alternative work is feasible), the employer may be considered in "creditor's default" (under Article 536, Paragraph 2 of the Civil Code). This could render the employer liable for the employee's wages for the period, even though the originally assigned work was not performed.

- For Employees (with non-job-specific employment contracts):

- If an employee becomes partially incapacitated for their current role due to a non-work-related illness but is capable of performing other suitable tasks within the company, they should proactively inform the employer and offer to perform those alternative duties.

- Importance of Contract Specificity: The ruling underscores the critical importance of how job roles and responsibilities are defined in employment contracts. If an employment contract specifically and narrowly defines the employee's job (e.g., "taxi driver"), then an inability to perform that specific job due to illness would generally mean the employee cannot offer valid performance, and the employer would not typically be obliged to find or accept alternative work like office duties, unless they choose to do so (as seen in the Kanagawa Toshi Kotsu case, a Supreme Court decision from 2008).

- Link to Reinstatement After Sick Leave: The Katayama Gumi judgment has significantly influenced how courts assess "recovery" or "fitness for work" for the purpose of an employee's reinstatement after a period of sick leave, particularly under non-job-specific contracts. The ability to perform some suitable work to which the employee could realistically be assigned within the company, even if it's not their exact pre-leave job, can be a key factor in determining that the employee is "cured" and eligible for reinstatement.

Conclusion

The Katayama Gumi Supreme Court decision provides vital guidance on the rights and obligations of employers and employees when a worker, under a non-job-specific employment contract, is unable to perform their currently assigned duties due to a non-work-related illness but remains capable of undertaking other tasks within the company. It establishes that a genuine offer to perform such realistically assignable alternative work can constitute a valid "offer of performance in accordance with the true aim and purpose of the obligation," potentially entitling the employee to wages even if the employer refuses the alternative work. The ruling champions a nuanced approach that considers the flexibility inherent in non-job-specific contracts, the employee's capabilities, the employer's operational realities, and the overarching principles of good faith in the employment relationship.