Canceling Long-Term Service Contracts in Japan: Supreme Court Voids Language School's Punitive Refund Math

Judgment Date: April 3, 2007

Many consumers are attracted to long-term service contracts—such as those for foreign language schools, gyms, or beauty salons—by the promise of discounted rates for bulk purchases or extended commitments. However, circumstances can change, leading a consumer to seek mid-term cancellation. A critical issue then arises: how should the refund for unused services be calculated? Can a business retroactively apply a higher, non-discounted unit price to the services already consumed, thereby significantly reducing the refund amount? The Supreme Court of Japan tackled this precise question in a landmark decision on April 3, 2007 (Heisei 17 (Ju) No. 1930), concerning a foreign language conversation school. This ruling provided crucial interpretation of Japan's Act on Specified Commercial Transactions (SCTA), reinforcing consumer protection in such contracts.

The Language School's "Point System," Tiered Pricing, and the Controversial Refund Clause

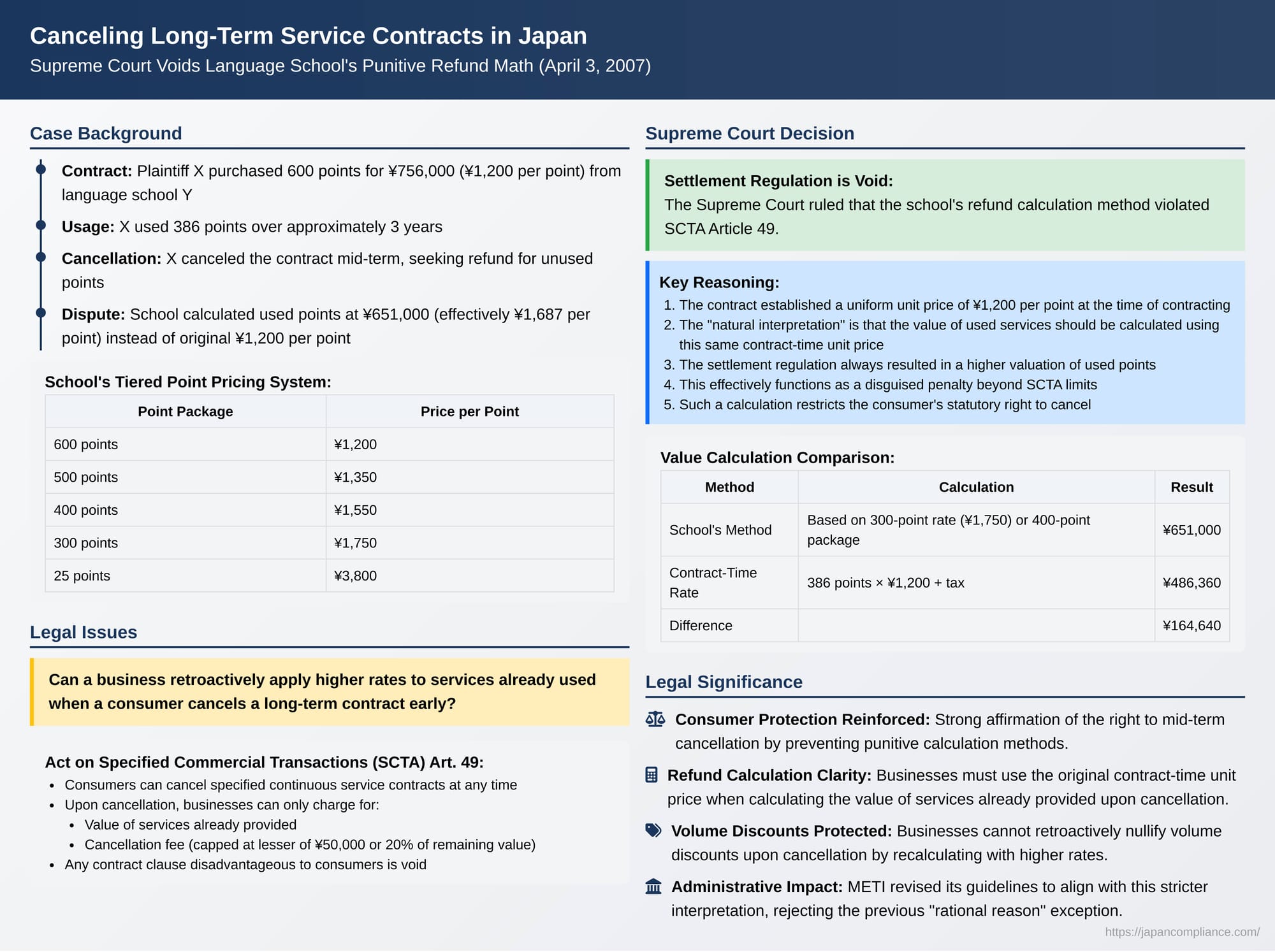

The defendant, Y, operated a chain of foreign language conversation schools. To receive lessons, students were required to pre-pay tuition to register for "points," with each point typically entitling the student to one lesson. Y's fee structure ("the Fee Regulation" - 本件料金規定) featured a tiered system for the unit price per point: the more points a student purchased upfront, the lower the per-point (and thus per-lesson) cost. For example:

- 600 points: ¥1,200 per point

- 500 points: ¥1,350 per point

- 400 points: ¥1,550 per point

- 300 points: ¥1,750 per point

- ...and so on, with the highest unit price for the smallest block of 25 points being ¥3,800 per point.

The plaintiff, X, entered into a contract with Y, paying ¥756,000 (including consumption tax) to register for 600 points. This established a "contract-time unit price" (契約時単価 - keiyakuji tanka) of ¥1,200 per point for X.

Approximately three years later, X decided to cancel the contract mid-term. By this time, X had used 386 of the 600 registered points. The dispute centered on how Y calculated the value of these 386 used lessons for the purpose of determining X's refund. Y's contract included a "Settlement Regulation" (本件清算規定) for mid-term cancellations, which stipulated a complex calculation method:

- Refund Amount: Y would refund the total tuition paid, minus the "value of used points," a mid-term cancellation fee, and other applicable deductions.

- Calculating "Value of Used Points": Instead of using the student's actual contract-time unit price, this clause stated that the value of used points would be calculated by multiplying the number of used points by the unit price corresponding to the closest registered point block that was less than or equal to the number of points actually used.

- Proviso: If the amount calculated under step 2 exceeded the total tuition fee for the next higher registered point block that was closest to the number of points actually used, then that higher block's total tuition fee would be deemed the "value of used points."

- Mid-term Cancellation Fee: This was set at 20% of the remaining balance after deducting the value of used points (as calculated above), capped at ¥50,000.

Following its Settlement Regulation, Y calculated the value of X's 386 used points not at X's contract-time unit price of ¥1,200, but as follows:

- The closest registered point block less than or equal to 386 points was the 300-point block, which had a unit price of ¥1,750. (386 points x ¥1,750 + tax = ¥709,275).

- However, under the proviso, the closest registered point block exceeding 386 points was the 400-point block. The total tuition for 400 points (400 points x ¥1,550/point ) plus tax was ¥651,000.

- Since the first calculation (¥709,275) exceeded the cost of the 400-point block (¥651,000), Y asserted that the value of X's 386 used points was ¥651,000.

X contested this, arguing that the Settlement Regulation violated the SCTA and was therefore void. X maintained that the value of the 386 used points should be calculated using the contract-time unit price of ¥1,200 per point, resulting in a value of ¥486,360 (386 x ¥1,200 + tax). X sued Y for a refund based on this significantly lower valuation of consumed services.

The first instance court and the Tokyo High Court both ruled in favor of X. The High Court reasoned that when calculating the value of services already provided upon mid-term cancellation, the contract-time unit price should, in principle, be used. Employing a different unit price without a "rational reason" was deemed contrary to the spirit of SCTA Article 49, Paragraph 2. The High Court found no such rational reason for Y's Settlement Regulation and thus held it void. Y appealed this decision to the Supreme Court.

The Legal Framework: SCTA Article 49 and Consumer Protection

The Act on Specified Commercial Transactions (特定商取引に関する法律 - Tokutei Shō Torihiki ni Kansuru Hōritsu, or SCTA) plays a crucial role in regulating certain types of business transactions prone to consumer disputes. Foreign language schools, along with other services like aesthetic salons, private tutoring, and cram schools, that offer services over an extended period (typically exceeding two months for language schools) for a significant fee (exceeding ¥50,000) are designated as "Specified Continuous Service Contracts" (特定継続的役務提供契約 - tokutei keizokuteki ekimu teikyō keiyaku) under SCTA Article 41.

Article 49 of the SCTA provides consumers with important protections for these contracts:

- Right to Mid-Term Cancellation (Art. 49(1)): Even after any statutory cooling-off period has passed, consumers have the right to cancel these contracts at any time, prospectively (i.e., for the future).

- Limitation on Charges Upon Cancellation (Art. 49(2)): When a contract is cancelled after services have commenced, the business operator cannot demand payment from the consumer exceeding the sum of:

- (a) An amount equivalent to the consideration for the Specified Continuous Services already provided (提供された特定継続的役務の対価に相当する額).

- (b) An amount for damages or penalties associated with the cancellation, which is statutorily capped. For foreign language schools, this cap is the lower of ¥50,000 or 20% of the value of the remaining contract services.

- Voidness of Non-Compliant Clauses (Art. 49(7)): Any special contract clause that is disadvantageous to the consumer and contravenes the provisions of Article 49 (including the limits in Paragraph 2) is void.

These provisions were introduced to address widespread problems where consumers were subjected to high-pressure sales tactics for long-term contracts, often with insufficient information about service quality or unclear and unfair cancellation terms, leading to forfeiture of substantial prepayments or imposition of excessive penalties.

The Supreme Court's Decision: Contract-Time Unit Price Must Be Used for Refund Calculation

The Supreme Court dismissed Y's appeal, thereby upholding the decisions of the lower courts in favor of X. The Court's reasoning provided a definitive interpretation of SCTA Article 49(2)(i)(a) concerning the calculation of the "value of services already provided."

- Uniform Value Agreed at Contract Time: The Supreme Court began by analyzing Y's own Fee Regulation. It observed that when X entered into the contract for 600 points, a single, uniform unit price of ¥1,200 per point was established for all lessons X would receive under that specific contract. There was no indication in the Fee Regulation that different individual lessons taken under this 600-point agreement would be valued differently at the time of contracting.

- The "Natural" Method of Calculation: Given this uniform contract-time unit price, the Court found it "natural to interpret" (自然というべきである - shizen to iu beki de aru) that the value of the 386 points X had already used should also be calculated based on this same ¥1,200 per-point contract-time unit price.

- Settlement Regulation as a Disguised Penalty: The Supreme Court then scrutinized Y's Settlement Regulation. It noted that the value of used points calculated according to this regulation would always result in a higher amount than if calculated using the student's original contract-time unit price. Since the Fee Regulation (the basis of the original contract) established a uniform per-lesson value, the Settlement Regulation—which imposed a separate, higher valuation applicable only in the event of mid-term cancellation—was, in substance and effect, a liquidated damages or penalty clause (損害賠償額の予定又は違約金の定め - songai baishōgaku no yotei mata wa iyakukin no sadame) in disguise. It was not a genuine reflection of the agreed-upon value of the individual lessons X had consumed.

- Restriction of the Statutory Right to Cancel: By making mid-term cancellation significantly more costly for the consumer (by artificially inflating the value attributed to consumed services), this disguised penalty effectively discourages and restricts the consumer's statutory right to freely cancel the contract under SCTA Article 49(1). This, the Court found, runs contrary to the protective purpose of Article 49.

- Violation of SCTA Article 49(2)(i) and Voidness: The Supreme Court concluded that Y's Settlement Regulation, by seeking to make the consumer effectively pay an amount for consumed services that was higher than their agreed contract-time value (and thus reducing the refundable amount), was a mechanism to claim monies beyond the limits permitted by SCTA Article 49, Paragraph 2, Item 1. Specifically, it improperly inflated component (a) of the SCTA calculation – the "amount equivalent to the consideration for the services already provided." Therefore, the Settlement Regulation was void under SCTA Article 49, Paragraph 7. The correct method for determining the "amount equivalent to the consideration for the services already provided" in X's case was to use the contract-time unit price of ¥1,200 per point.

Analyzing the Impact and Rationale of the Supreme Court's Ruling

This Supreme Court decision was a significant victory for consumer protection in Japan concerning long-term service contracts.

- Robust Protection of the Right to Cancel: The ruling strongly affirms the consumer's statutory right to mid-term cancellation under the SCTA by preventing businesses from using convoluted or punitive refund calculation methods that effectively penalize cancellation beyond the SCTA's explicit caps on damages and penalties.

- Addressing Information Asymmetry and Unfair Terms: The SCTA itself, and this judgment interpreting it, targets common problems in these types of contracts, such as information asymmetry, unclear terms, and the imposition of unfair burdens on consumers who wish to exit contracts that may no longer meet their needs or that were entered into under pressure.

- Distinction Between Legitimate Volume Discounts and Illegitimate Cancellation Penalties: The case effectively clarifies that while businesses can legitimately offer volume discounts (i.e., a lower unit price for a larger upfront commitment), they cannot retroactively nullify these discounts upon a consumer's statutory mid-term cancellation by re-valuing the services already consumed at a higher, non-discounted rate, if this was not the per-unit value agreed upon at the time of contract formation. The discount is for the commitment to the volume, not a conditional benefit that can be clawed back through creative accounting upon early termination in a way that circumvents SCTA limits.

- Revision of Administrative Guidance: The impact of this judgment was immediate and significant. The Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI), which oversees the SCTA, promptly revised its administrative guidelines to align with the Supreme Court's stricter interpretation. This rejected the previous, more lenient stance (which some lower courts, including the initial ones in this case, had followed) that allowed businesses to use a different (higher) unit price upon cancellation if they could show a "rational reason" for it. The Supreme Court's ruling effectively closed this "rational reason" loophole for SCTA-regulated services.

- Scope of Application: It's important to understand that this ruling's direct application is to "Specified Continuous Service Contracts" as defined and regulated by the SCTA. These contracts have specific characteristics: they are often long-term, involve pre-payment, the quality or outcome of the service is often uncertain at the outset, and they have historically been associated with aggressive sales practices. The ruling's direct extension to other types of contracts with volume discounts or early termination fees (e.g., certain telecommunication plans, season tickets for transport or entertainment, if not covered by specific SCTA provisions) is not automatic and would depend on the specific terms of those contracts and any other applicable laws. The SCTA provides a particular level of protection for the designated service types due to their inherent risks to consumers.

From an equity perspective, the judgment is also seen as reasonable. Businesses offering these long-term, pre-paid services gain a considerable upfront cash flow advantage, often for services whose ultimate benefit to the consumer is uncertain. Allowing them to then penalize early cancellation through punitive refund calculations would further tilt the balance unfairly. While businesses might argue that those who cancel early shouldn't benefit from the best bulk rates, the SCTA's framework for cancellation (allowing recovery for services provided plus a capped damage/penalty fee) already provides a mechanism for businesses to recoup reasonable costs and some compensation for the early termination.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's April 2007 decision in the foreign language school case firmly established that for long-term service contracts regulated by Japan's Act on Specified Commercial Transactions, any contract clause that re-calculates the value of services already consumed using a higher unit price upon mid-term cancellation—different from the unit price agreed upon at the time of contract formation for a bulk purchase—is generally void. Such clauses are viewed as disguised penalties that unlawfully restrict the consumer's statutory right to cancel. Refunds for unused services must therefore be calculated based on the per-service value as established by the original contract terms, ensuring that consumers are not unduly penalized for exercising their right to terminate contracts that no longer serve them. This ruling reinforces a key principle of consumer protection: clarity in pricing and fairness in cancellation.