Can You Insult a Corporation? A Deep Dive into a Landmark Japanese Supreme Court Ruling

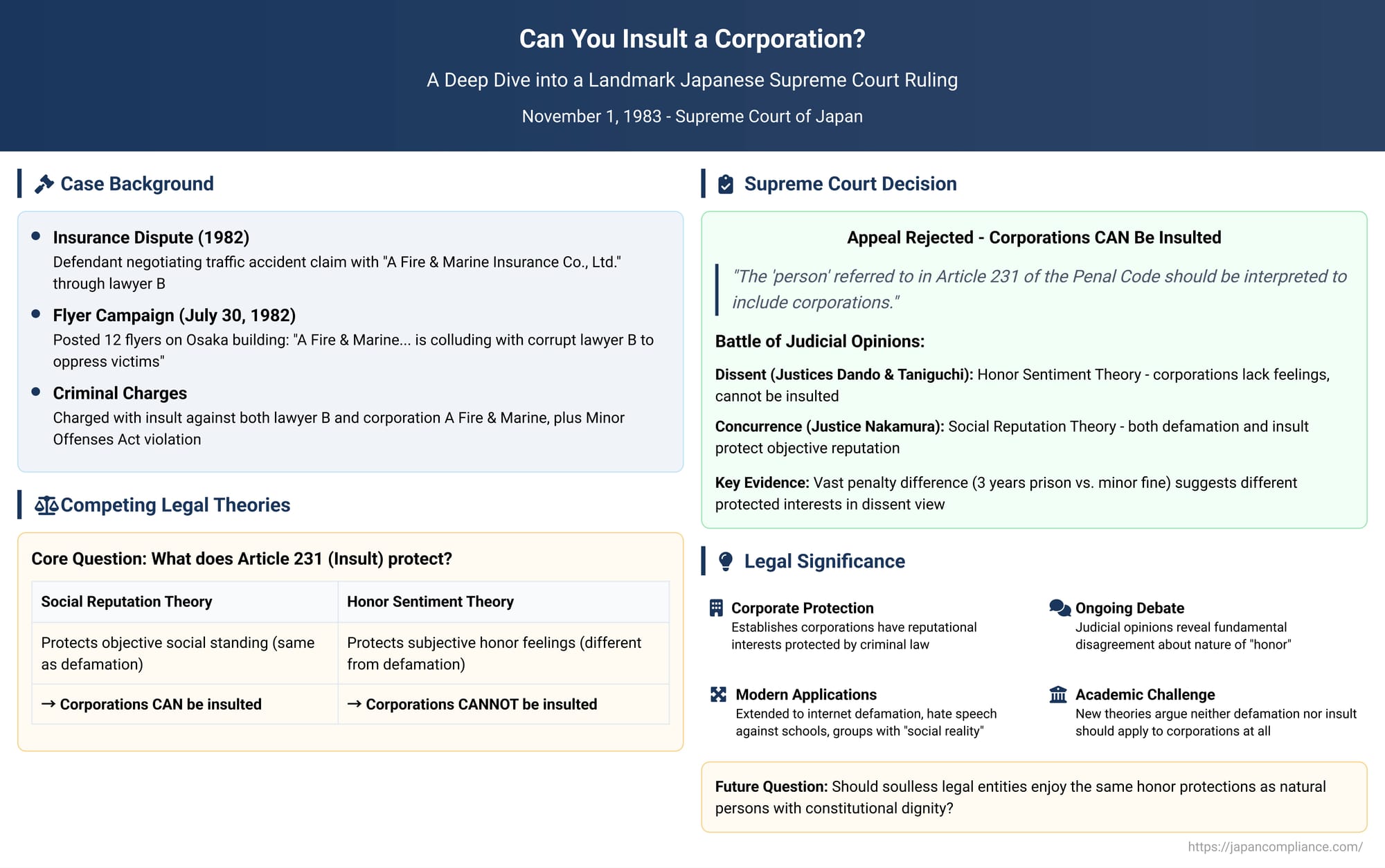

Can a corporation—an entity of legal fiction without consciousness or feelings—be the victim of the crime of "insult"? This question, which probes the very nature of reputation and the purpose of laws designed to protect it, was the subject of a pivotal, though deeply divided, decision by the Supreme Court of Japan on November 1, 1983. The case, involving angry flyers posted by a man in a dispute with an insurance company, produced a terse majority ruling that affirmed corporations can indeed be insulted.

However, the enduring legacy of the decision lies not in its brief conclusion, but in the detailed and conflicting judicial opinions attached to it. These opinions lay bare a fundamental debate in Japanese criminal law: does the crime of insult protect a person's objective social standing, or their subjective sense of honor? The answer determines whether a soulless legal entity can have a reputation worthy of the law's protection against abstract insult.

The Facts: The Angry Flyers and the Insurance Company

The case originated from a dispute between the defendant and an insurance company, "A Fire & Marine Insurance Co., Ltd.," over a traffic accident claim. The defendant was negotiating on behalf of an acquaintance with the company's consulting lawyer, B. Seeking to pressure the company and its lawyer, the defendant, along with several accomplices, took action in the early morning hours of July 30, 1982. They pasted twelve flyers on a building pillar in Osaka, which read:

"A Fire & Marine, a related company of D Marine, is colluding with the corrupt lawyer B to oppress victims. Both companies must take responsibility!"

This act was done without the permission of the building's manager and led to the defendant being charged with violating the Minor Offenses Act, as well as the crime of insult against both the lawyer B and the corporation, A Fire & Marine. The lower courts found him guilty on all counts, and the case was appealed to the Supreme Court on the question of whether the insurance company could legally be a victim of insult.

The Core Legal Question: What Does the Crime of "Insult" Protect?

The case hinged on the interpretation of Article 231 of the Japanese Penal Code, which defines the crime of insult. Unlike the crime of defamation (Article 230), which involves stating specific facts, insult typically involves expressing abstract contempt or derision without specific factual allegations. The central question for the Court was defining the "protected legal interest" (hogo hōeki) of this crime. Two competing theories were at the forefront:

- The Social Reputation Theory: This theory holds that the crime of insult, just like defamation, protects a "person's" objective social reputation—their standing and evaluation in the eyes of society.

- The Honor Sentiment Theory (The "Distinction Theory"): This theory argues for a distinction between the two crimes. While defamation protects objective social reputation, insult protects a person's subjective "honor sentiment" (meiyo kanjō)—their internal feelings of self-worth and dignity.

The choice between these theories is decisive. If insult protects objective reputation, a corporation, which indisputably has a social and commercial reputation, can be a victim. If it protects subjective honor sentiment, a corporation, lacking feelings, cannot.

The Supreme Court's Terse Ruling

The majority of the Supreme Court issued a very brief decision, rejecting the appeal and upholding the conviction. It stated simply and authoritatively:

"The 'person' referred to in Article 231 of the Penal Code should be interpreted to include corporations."

In support, the Court cited a 1926 precedent from the pre-war Great Court of Cassation, which had recognized in an obiter dictum that organizations with legal personality could be victims of defamation and insult. With that, the majority considered the matter settled.

The Heart of the Matter: The Battle of the Justices' Opinions

The true intellectual substance of the ruling is found in the lengthy separate opinions written by the justices, which passionately argued the two opposing viewpoints.

The Dissenting View (The "Honor Sentiment" Camp)

Justices Dando and Taniguchi wrote a powerful dissent, arguing that a corporation cannot be insulted. Their reasoning followed the "Honor Sentiment Theory":

- Difference in Penalties: They argued that the enormous difference in statutory penalties between defamation (which can lead to up to three years in prison) and insult (which is punishable only by minor detention or a small fine) cannot be explained simply by the presence or absence of a factual allegation. This vast gap, they contended, must be rooted in a fundamental difference in what is being protected. The former protects objective reputation, while the latter protects the less tangible, subjective "honor sentiment".

- The Nature of Corporations: A corporation is a legal fiction. It can have a reputation, but it cannot have feelings, dignity, or a sense of self-worth in the human sense.

- Conclusion: Since the crime of insult protects honor sentiment, and corporations lack this sentiment, they cannot be victims of the crime.

The Concurring View (The "Social Reputation" Camp)

Justice Nakamura wrote a detailed concurring opinion to rebut the dissent and provide a robust defense of the majority's conclusion. His argument is the classic articulation of the "Social Reputation Theory":

- A Unified Protected Interest: He argued that the protected interest for both defamation and insult is objective social reputation. There is no compelling reason, he wrote, to believe the law carves out subjective honor sentiment as a separate interest protected by the crime of insult.

- Statutory Clues: The fact that both crimes require the act to be done "publicly" and are distinguished only by the presence of a factual allegation strongly suggests they share a common protected interest: social reputation.

- The Reality of Modern Society: In contemporary society, corporations are distinct social entities with their own activities, identities, and reputations that deserve legal protection. Their reputation is not merely about their credit rating or financial stability; it encompasses a broader social evaluation that can be harmed by public insult, and this harm is not adequately covered by other crimes like obstruction of business or discrediting.

Aftermath and the Evolving Debate

The majority opinion in the 1983 case became the definitive law in Japan, establishing that corporations can be the victims of both defamation and insult. Subsequent case law has built upon this foundation, applying it to new contexts like internet defamation against a franchise company and, significantly, to hate speech directed at a school corporation. A 2011 High Court case concerning hate speech notably suggested that formal legal personality is not even the decisive factor; rather, a group can be a victim of insult if it possesses a distinct "social reality".

However, the academic debate has continued to evolve. In recent years, a new and influential school of thought has emerged, arguing that neither defamation nor insult should apply to corporations at all. Proponents of this view argue that:

- The concept of "honor" is derived from the inherent dignity of the natural person, as guaranteed by Japan's Constitution, and should not be automatically extended to artificial legal entities.

- Corporations are primarily economic actors, and their reputational harms are economic in nature. These should be protected by civil law or by specific economic crimes like discrediting (which requires proof of falsehood), not by general defamation and insult laws that can punish true statements or abstract opinions.

Conclusion

The 1983 Supreme Court decision remains a landmark ruling in Japanese criminal law. It officially confirmed that corporations have a reputation that can be criminally "insulted," cementing the view that the crime protects objective social standing. Yet, the decision's true value lies in the profound debate it exposed through its separate opinions—a debate over the very meaning of honor and reputation in modern society. While the law is settled for now, the arguments raised by the dissent and the emergence of new academic theories ensure that the question of how, and why, we protect the "honor" of a soulless corporation will continue to be a vital topic of legal and philosophical discussion.