Can You Consent to Forgery? A Japanese Supreme Court Ruling on Signing a Friend's Name

Imagine a friend asks you to sign a document on their behalf. With their full knowledge and permission, you sign their name. In most everyday situations, this is a perfectly acceptable and legal act of agency. But what if the document is not a simple letter or contract, but a confession statement on a traffic ticket being issued by a police officer? Can a person's consent transform an act of impersonation into an authorized signature, or are there certain documents so personal in nature that no one else can sign them without committing a crime?

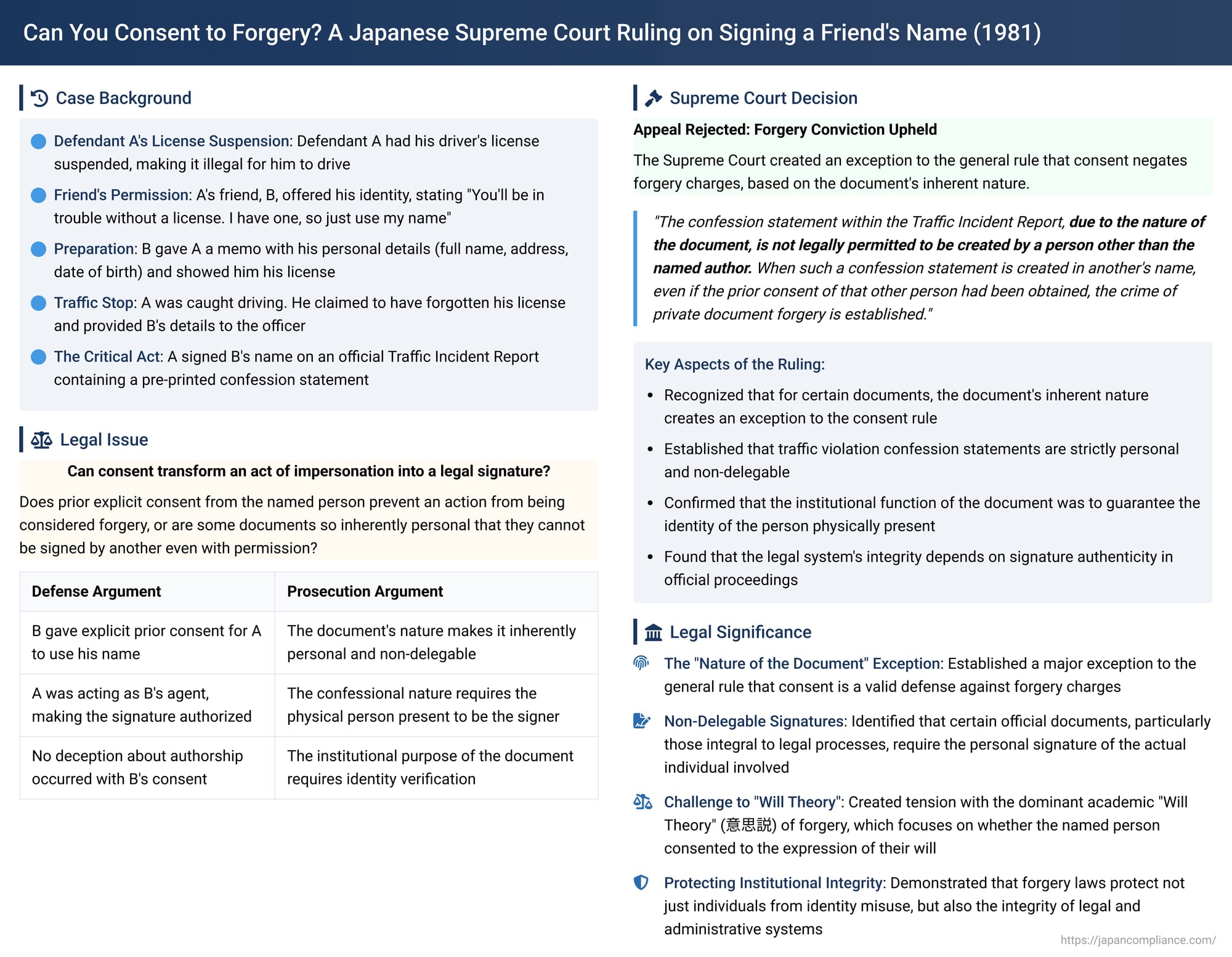

This fascinating question—pitting the principle of personal consent against the integrity of the legal process—was the subject of a landmark decision by the Supreme Court of Japan on April 8, 1981. The ruling established a crucial exception to the general rule that consent from the named party negates the crime of forgery, clarifying that for certain documents, their very "nature" makes a signature non-delegable.

The Facts: The Traffic Stop and the Friend's Favor

The case began with a simple arrangement between two business partners, whom we will call Defendant A and Friend B.

- The Arrangement: Defendant A had his driver's license suspended. Knowing this would be a problem, his friend, B, offered a solution. B told A, "You'll be in trouble without a license. I have one, so just use my name." To facilitate this, B showed A his own license and gave him a handwritten memo with his full name, legal address, date of birth, and other personal details. The lower court found that B had given A prior consent to sign B's name on his behalf.

- The Incident: Subsequently, A was caught driving while his license was suspended. When the police officer asked for his license, A claimed he had forgotten it at home and proceeded to give the officer his friend B's name and details.

- The Forged Document: The officer then filled out a "Traffic Incident Report" (kōtsū jiken genpyō). This official report included a section with a pre-printed confession statement, such as "I do not dispute that I committed the above violation." This confession statement is legally considered a private document concerning the proof of a fact. At the bottom of this statement, in the space for the violator's signature, Defendant A signed the name "B" and submitted the document to the police officer.

The Legal Question: Forgery, or an Authorized Signature?

The defendant was charged with Forgery of a Signed Private Document. His defense was straightforward: he had B's explicit, prior consent to use his name. In essence, he was acting as B's agent. Since the signature was authorized by the person whose name was being used, there was no criminal deception about the document's authorship, and therefore, no forgery. The lower courts rejected this argument and convicted him, prompting an appeal to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Ruling: The "Nature of the Document" Exception

The Supreme Court rejected the appeal in a brief but powerful decision. It carved out a major exception to the general rule that consent from the named person is a valid defense against a forgery charge. The Court held:

"The confession statement within the Traffic Incident Report, due to the nature of the document, is not legally permitted to be created by a person other than the named author. When such a confession statement is created in another's name, even if the prior consent of that other person had been obtained, the crime of private document forgery is established."

This ruling was a significant moment in Japanese forgery law, confirming that for certain classes of documents, the consent of the named party is legally irrelevant.

Analysis: When Consent is Not a Defense

The Supreme Court's decision hinges entirely on the phrase "due to the nature of the document." But what is it about the "nature" of a traffic violation confession that makes it so personal that the right to sign it cannot be delegated, even with consent?

- Institutional Function: The key is the document's role in the legal system. The Traffic Incident Report and its confession statement are designed for the simple, rapid, and massive-scale processing of routine violations. The entire system relies on the assumption that the person signing the confession on the spot is the same person who was physically apprehended by the officer. The signature serves as the primary, and often only, piece of evidence creating an undeniable link between the physical individual at the scene and the legal admission of the offense. Its purpose is to guarantee the identity of the confessor.

- A Non-Delegable Act: Because of this critical institutional function, the act of signing is considered strictly personal and non-delegable. Allowing one person to stand in for another would undermine the entire administrative and evidentiary basis of the traffic enforcement system.

This ruling poses a challenge to the dominant "Will Theory" (ishi setsu) of forgery in Japanese academia. This theory holds that the author of a document is the person whose will or idea is expressed in it. Under a strict application of this theory, since B factually consented to the act, the signature could be seen as an expression of B's will, meaning B would be the author and no forgery would have occurred.

To reconcile the Supreme Court's decision with legal theory, some scholars have proposed a more nuanced interpretation.

- The "Qualified Author" View: This perspective argues that the true "author" of this specific document is not just "Person B," but more precisely, "Person B, as the violator identified by the police officer at the scene." Since Defendant A, not B, was the person physically present and identified as the driver, A could never be this "qualified" person. Therefore, even with B's consent, a discrepancy in personality exists between the actual creator (A) and the required, qualified author. This interpretation, however, has been criticized for blurring the line between tangible forgery (faking an identity) and intangible forgery (faking the content, i.e., who was actually driving).

Ultimately, the most straightforward understanding of the Court's position is that it has carved out a policy-based exception for a specific class of documents. The institutional need for a strict identity match in legal proceedings like a traffic stop outweighs the general principle of private autonomy that allows one person to consent to another using their name.

Conclusion

The 1981 Supreme Court decision is a crucial lesson in the limits of consent in criminal law. It established that for certain documents—particularly those integral to the functioning of public administrative and legal systems—the "nature" of the document itself can render a signature non-delegable. In these situations, signing another person's name constitutes forgery, and the consent of the named individual is no defense. The ruling affirms that the crime of forgery protects not only individuals from the misuse of their identity but also the integrity of the critical processes that rely on the authentic, personal verification of facts.