Can International Customary Law Create Direct Claims Against the State? A Japanese Supreme Court Case on Post-War Compensation

Date of Judgment: March 13, 1997

Supreme Court of Japan, First Petty Bench

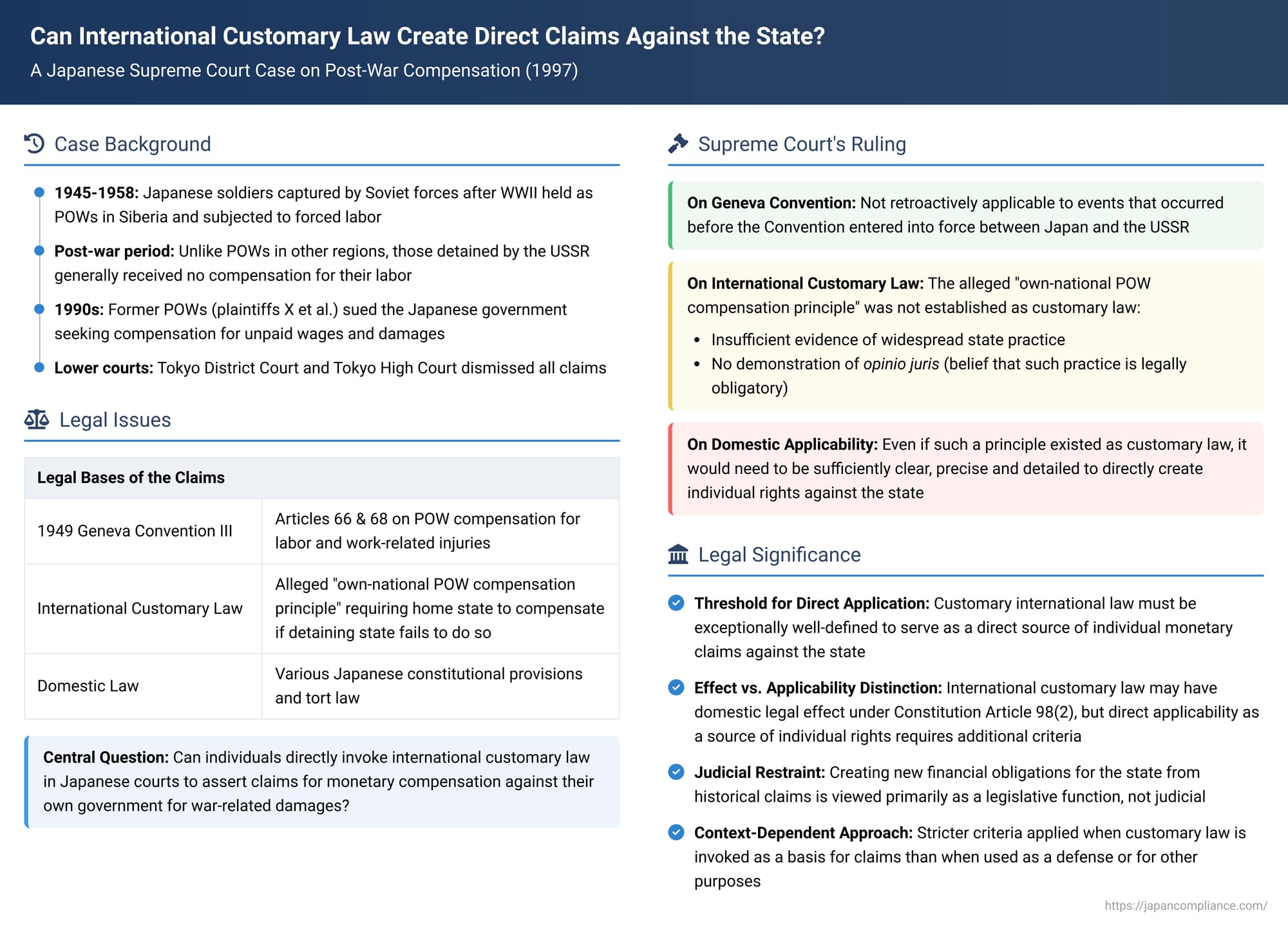

Article 98, paragraph 2 of the Constitution of Japan provides that "treaties concluded by Japan and established laws of nations shall be faithfully observed." This incorporates international law into Japan's domestic legal order. However, the extent to which individuals can directly invoke international customary law in Japanese courts to assert claims against the State, particularly for monetary compensation, has been a subject of legal debate. A significant Supreme Court decision on March 13, 1997, in a case brought by former Japanese prisoners of war (POWs) detained in Siberia after World War II, shed light on the judiciary's approach to the domestic applicability of alleged principles of international customary law.

The Factual Background: A Tragic Legacy of WWII

The case was initiated by X et al. (plaintiffs), former Japanese soldiers who were captured by the Soviet Union at the end of World War II.

- Following Japan's surrender in August 1945, Soviet forces disarmed Japanese troops and interned them as POWs in numerous camps, primarily in Siberia.

- These POWs were subjected to forced labor under harsh conditions. Their repatriation to Japan was significantly delayed, with the final returns occurring around 1958, nearly 12 years after most POWs held by other Allied nations had returned.

- Unlike some POWs returning from other regions who received certificates for credit balances for their labor, those detained by the Soviet Union generally did not receive such documentation or payment for their work during captivity.

- X et al. filed a lawsuit against Y (the State of Japan), seeking various forms of compensation. Their claims were based on several grounds, including:

- The 1949 Geneva Convention III (relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War), specifically Articles 66 (settlement of accounts upon release) and 68 (compensation for work accidents). A key issue here was the convention's retroactivity, as Japan and the USSR ratified it after the POW status of most plaintiffs had ended.

- An alleged principle of international customary law referred to as the "own-national POW compensation principle." The plaintiffs argued that under this principle, the POW's home state (Japan) had an obligation to compensate its own nationals for unpaid labor wages, injuries, and other damages suffered during captivity if the detaining state (Soviet Union) failed to do so.

- Various provisions of the Japanese Constitution and domestic laws related to state redress, tort, and breach of a duty of care.

The Tokyo District Court (first instance) and the Tokyo High Court (second instance) dismissed all of X et al.'s claims. The plaintiffs then appealed to the Supreme Court. This blog post will focus on the Supreme Court's treatment of the arguments related to international customary law.

The Supreme Court's Key Findings on International Law Claims

The Supreme Court ultimately dismissed the appeal. Its reasoning regarding the international law claims was as follows:

1. 1949 Geneva Convention III Not Retroactively Applicable:

The Supreme Court affirmed the High Court's finding that the 1949 Geneva Convention could not be applied retroactively to events and legal relationships that had concluded before the Convention entered into force between Japan and the Soviet Union. The Convention itself did not contain explicit provisions mandating such retroactive application for the specific claims being made.

2. The Alleged "Own-National POW Compensation Principle" Not Established as International Customary Law:

This was a central part of the plaintiffs' international law argument.

- Definition of International Customary Law: The Supreme Court endorsed the High Court's articulation of the two essential elements for the formation of a rule of international customary law:

- Widespread and consistent state practice among a significant majority of states, including major powers.

- Opinio juris sive necessitatis: A belief among these states that such practice is followed because it is legally obligatory.

- No Such Customary Principle Found: The Supreme Court upheld the High Court's detailed analysis. The High Court had examined the drafting history of the 1949 Geneva Conventions and historical state practice concerning POW compensation. It concluded that:

- Articles 66 and 68 of the 1949 Geneva Convention did not merely codify a pre-existing customary law principle obliging a home state to compensate its own POWs for the detaining state's failures.

- At the time of the plaintiffs' detention by the Soviet Union, there was no established general state practice, supported by opinio juris, that formed an international customary law principle of "own-national POW compensation" as alleged by the plaintiffs. While customary international law regarding the basic humane treatment of POWs was evolving and solidifying, a specific rule mandating home-state compensation for unpaid labor or injuries due to the detaining state's actions had not crystallized into customary law.

3. Domestic Applicability of International Customary Law (and the High Court's More Detailed Reasoning):

The Supreme Court itself dealt with this point very briefly in its judgment. Because it found that no relevant rule of international customary law (the "own-national POW compensation principle") actually existed, it stated that any alleged errors by the High Court concerning the general theory of domestic applicability of customary law would not affect the outcome of the case.

However, the High Court's prior reasoning on this point (which the Supreme Court did not overturn in its theoretical aspects) is considered significant by legal commentators and provides insight into Japanese judicial thinking:

- Domestic Effect vs. Domestic Applicability: The High Court distinguished between the "domestic effect" of international law and its "domestic applicability." It acknowledged that established international customary law, like treaties, has domestic legal effect in Japan under Article 98, paragraph 2 of the Constitution, generally without requiring specific implementing legislation by the Diet.

- Criteria for Direct Domestic Applicability: However, the High Court posited that for an international customary law norm to be directly applicable by domestic courts to create specific rights for individuals or impose obligations on the state, especially if such application would lead to public expenditure or necessitate harmonizing with existing domestic legal frameworks, the content of that customary norm must be sufficiently clear, precise, and detailed. It would need to clearly define the conditions for the creation of rights, their substance, effects, and procedural requirements for their exercise, and demonstrate consistency with Japan's existing legal systems.

- The High Court found that the alleged "own-national POW compensation principle" was too general and abstract to meet these demanding criteria for direct domestic applicability as a source of individual monetary claims against the Japanese government. The first instance court had framed this in terms of "self-executing force" (自動執行性 - jidō shikkōsei), arguing that the principle lacked the necessary clarity and detail to be self-executing.

Significance and Commentary Insights

This "Siberian Internees" case is highly significant for its discussion (particularly at the High Court level, implicitly not rejected by the Supreme Court on this theoretical point) of the conditions under which international customary law might be directly applied by Japanese courts to found individual claims against the State:

- Judicial Caution on Direct Application of Customary Law for Individual Monetary Claims Against the State: The case demonstrates a cautious approach by the Japanese judiciary. While international customary law is an integral part of Japan's legal order, its direct invocation by individuals to establish monetary claims against the government, especially for historical grievances not covered by specific domestic legislation, faces a high threshold. Courts will scrutinize whether the alleged customary norm is sufficiently clear, precise, and detailed to be directly applied as a source of individual rights and state obligations.

- The Role of Domestic Legislation: The underlying sentiment is that creating new financial obligations for the state, especially for widespread historical claims, is primarily a matter for the legislature, which can consider broader policy implications, budgetary constraints, and the overall framework of national compensation schemes. Courts are generally reluctant to step into this legislative domain by creating such rights directly from general principles of international customary law unless those principles are exceptionally well-defined and clearly intended to create such individual entitlements directly.

- Distinction from Other Contexts of Customary Law Application: As pointed out by legal commentators like Professor Koh, the stringency of the criteria for direct applicability of customary law may vary depending on the context. The requirements might be different when customary law is invoked as a defense (e.g., the principle of sovereign immunity, which is a well-established customary rule directly applied by courts), or when it underpins state actions in international relations (e.g., rights over the continental shelf), compared to when it is asserted as the direct source of an individual's right to claim monetary compensation from their own government for harms caused by third states or historical events.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 1997 decision in the Siberian Internees case affirmed that claims for compensation from the Japanese government based on alleged breaches of the 1949 Geneva Conventions (applied retroactively) or a purported international customary law principle of "own-national POW compensation" were unfounded. More broadly, the case (especially through the reasoning of the lower courts which was not disturbed on its general theoretical points regarding applicability) highlights the cautious approach of Japanese courts when asked to directly apply general principles of international customary law to create new financial obligations for the State in the absence of clear domestic legislation. While international customary law is part of Japan's domestic law, its direct application to establish individual monetary claims against the government requires a high degree of clarity, precision, and specificity in the customary norm itself—a standard that the principles invoked by the plaintiffs in this tragic case were found not to meet. The resolution of such large-scale historical claims, the courts suggest, generally lies within the domain of legislative policy rather than direct judicial creation of rights from customary international law.