Can 'Holdover' Directors Be Sued for Dismissal? A Japanese Supreme Court Ruling on Continuing Duties and Shareholder Actions

Case: Action for Dismissal of a Director

Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench, Judgment of February 26, 2008

Case Number: (Ju) No. 1443 of 2007

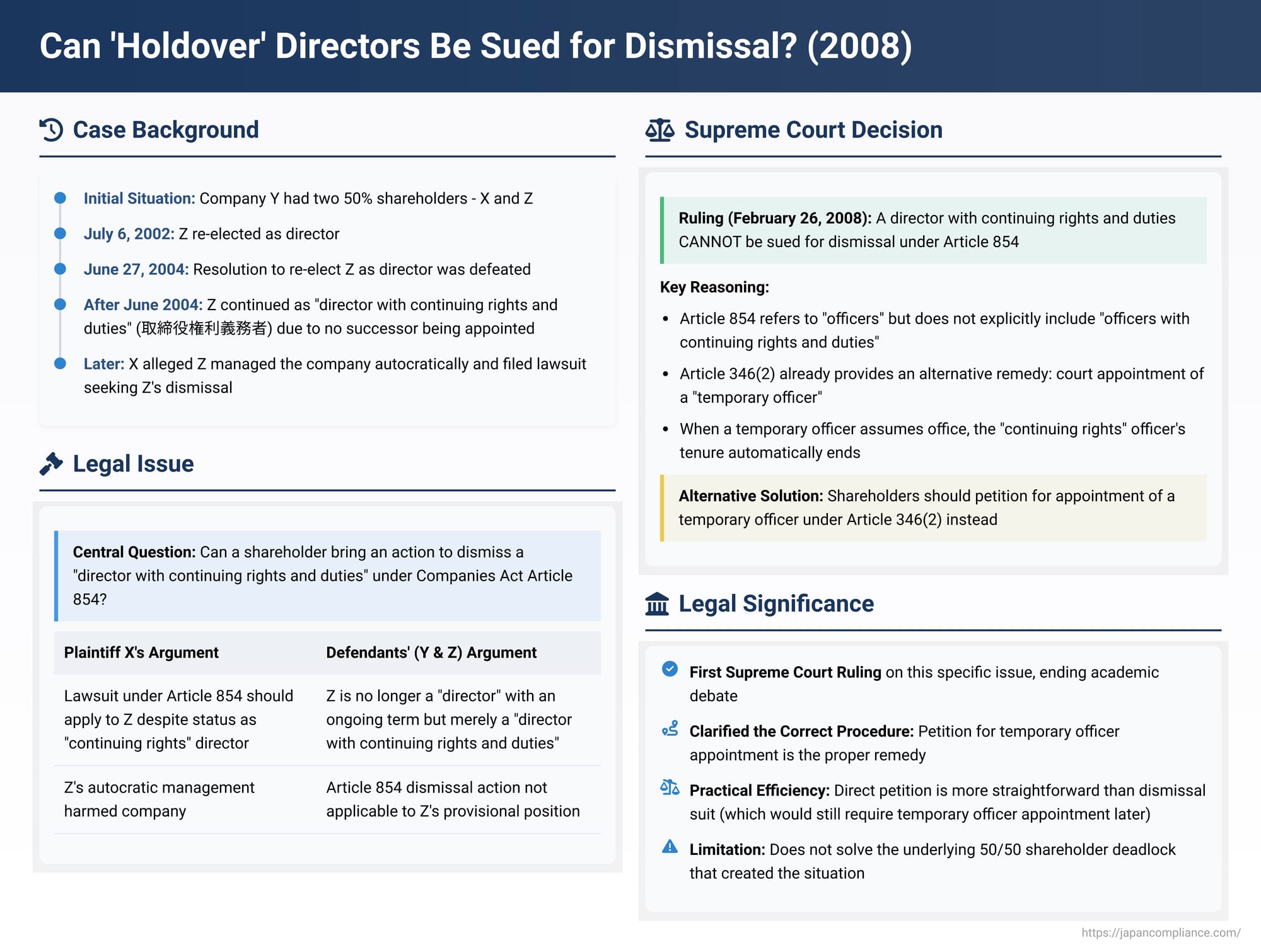

Japanese company law provides a mechanism for directors whose terms have expired or who have resigned to continue exercising their rights and duties if a successor has not yet been appointed, particularly if their departure would leave the company below the legally required number of directors. This "director with continuing rights and duties" (取締役権利義務者 - torishimariyaku kenri gimu sha), as per Article 346, Paragraph 1 of the Companies Act, ensures that a company is not left without leadership. But what happens if such a 'holdover' director engages in misconduct, and shareholder deadlock prevents the appointment of a new director? Can shareholders then resort to a lawsuit to dismiss this director under Article 854 of the Companies Act? The Supreme Court of Japan addressed this precise issue in a significant judgment on February 26, 2008.

Deadlock and a Director's Lingering Role: Facts of the Case

The dispute arose within Company Y, a closely-held family company. X, a shareholder, held exactly half of Company Y's 560 issued shares (280 shares). Z, another individual, held the other half (also 280 shares). Z had been re-elected as a director of Company Y at a shareholders' meeting on July 6, 2002. However, at a subsequent shareholders' meeting held on June 27, 2004, a resolution to re-elect Z as a director was defeated.

Despite this defeat, because a successor was not appointed (presumably due to the 50/50 deadlock between X and Z preventing any resolution to elect a new director), Z continued to perform directorial duties. Z did so under the status of a "director with continuing rights and duties" as stipulated by Article 346, Paragraph 1 of the Companies Act.

X alleged that Z, in this continuing capacity, was managing Company Y in an autocratic and arbitrary manner, detrimental to the company. Consequently, X filed a lawsuit against Company Y and Z, seeking Z's dismissal from the position of director pursuant to Article 854 of the Companies Act. This article allows shareholders, under certain conditions (such as when a resolution to dismiss a director is rejected by shareholders despite misconduct), to sue for a court-ordered dismissal.

The defendants, Company Y and Z, contested this. Their primary argument was that Z was no longer, strictly speaking, a "director" whose term was ongoing. Instead, Z was merely a "director with continuing rights and duties," a status that arose precisely because his term had effectively ended with the failed re-election. They argued, therefore, that an action for the dismissal of a director under Article 854 was not applicable to someone in Z's provisional position.

The Lower Courts' View: Not a "Director" for Dismissal Purposes

The court of first instance sided with the defendants and dismissed X's lawsuit as improper. It reasoned that Article 854, providing for a shareholder lawsuit to dismiss a director, was not intended to apply to individuals holding the merely provisional status of a "director with continuing rights and duties." The court also found it contradictory to seek to "dismiss" someone who had, in effect, already retired from their formal term.

X appealed, but the High Court upheld the first instance court's decision, leading X to appeal to the Supreme Court, which accepted the case for review.

The Supreme Court's Decision: No Direct Dismissal Suit Allowed

The Supreme Court, in its judgment of February 26, 2008, dismissed X's appeal, thereby affirming the lower courts' conclusions that a direct lawsuit under Article 854 to dismiss a "director with continuing rights and duties" is not permissible.

Reasoning of the Apex Court: Statutory Interpretation and Alternative Remedies

The Supreme Court provided three main reasons for its decision:

- Statutory Language of Article 854: The Court noted that Article 854 of the Companies Act, which outlines the shareholder's suit for dismissal of an officer, refers to the target of such a suit simply as an "officer" (yakuin). The provision does not explicitly state that the term "officer" in this context includes "officers with continuing rights and duties" (yakuin kenri gimu sha).

- Availability of an Alternative Remedy – Appointment of a Temporary Officer: The Court highlighted Article 346, Paragraph 2 of the Companies Act. This provision empowers a court, upon the petition of an interested party, to appoint a "temporary officer" (kari yakuin) to carry out the duties of an officer if the court deems it necessary. The Supreme Court reasoned that if an officer with continuing rights and duties (like Z) engages in misconduct or other serious wrongful acts, and if it's impossible to elect a new officer (for instance, due to shareholder deadlock, as in this case), then shareholders can petition the court for the appointment of a temporary officer. Such a situation would qualify as one where a temporary officer is "necessary."

- Effect of Temporary Officer Appointment on the "Continuing Rights" Officer: Crucially, Article 346, Paragraph 1 itself states that an officer with continuing rights and duties shall continue to hold such rights and duties "until a newly elected officer assumes office." The Supreme Court pointed out that the term "newly elected officer" as used here is understood to include a "temporary officer" appointed by the court under Article 346, Paragraph 2. Therefore, even if there isn't a specific statutory mechanism to "dismiss" an officer with continuing rights and duties via an Article 854 lawsuit, shareholders have an effective means to remove such an individual from their position: by successfully petitioning for the appointment of a temporary officer. Once a temporary officer assumes office, the tenure of the "officer with continuing rights and duties" ends.

Given these points, the Supreme Court concluded that a shareholder lawsuit seeking the dismissal of an officer with continuing rights and duties under Article 854 is not a procedure contemplated by the Companies Act.

Analysis and Implications: Navigating Governance Gaps

This 2008 Supreme Court decision was the first by Japan's highest court on this specific and important issue, offering significant clarification for both legal theory and practice.

- The Nature of "Officers with Continuing Rights and Duties":

This status under Article 346, Paragraph 1 is a statutory safeguard designed to prevent a vacuum in corporate governance when an officer's term ends (or they resign) and a successor is not immediately appointed. Although the formal mandate (delegation relationship under Article 330) between the company and the officer has technically concluded, the law extends their rights and duties to ensure continuous operation, akin to a receiver's duty under the Civil Code to manage affairs after the termination of a mandate.

Ordinarily, if such an officer engages in misconduct, the standard corporate response would be to elect a successor (thereby terminating the continuing duties of the problematic officer) and then pursue any necessary liability claims. The problem, as starkly illustrated by this case, arises when shareholder deadlock makes the election of a successor impossible. This practical impasse led shareholder X to attempt the novel application of Article 854. - Context of Previous Jurisprudence and Academic Views:

It's a general principle that a lawsuit for an officer's dismissal under Article 854 is a formative action aimed at terminating their legal status for the remainder of their term. Consequently, if an officer's term has already expired, a suit to dismiss them typically lacks the "interest to sue" (a necessary condition for maintaining a lawsuit).

Before this Supreme Court ruling, some lower courts had touched upon similar issues. A 1985 Tokyo High Court decision (in a case concerning a provisional disposition rather than a full dismissal suit) indicated that a director whose term had passed, even if continuing duties, was no longer a "director" in the sense of being a target for a dismissal suit. A 1986 Nagoya District Court decision directly dismissed a shareholder's attempt to sue for the dismissal of a "director with continuing rights and duties," citing the lack of explicit legal provision and the provisional nature of the status, suggesting shareholders should instead focus on electing a new director.

Academic opinion was divided:- The majority negative view (which the Supreme Court ultimately endorsed) argued that the "continuing rights and duties" status is conferred by statute and cannot be revoked by a shareholder resolution or a dismissal suit. Proponents of this view emphasized that the appropriate remedy was to petition for the appointment of a temporary officer. They also pointed to the conceptual difficulty of "dismissing" an officer who has, in a sense, already retired from their fixed term.

- A minority affirmative view argued that Article 854 should be applied, at least by analogy. Their reasons included the practical difficulty of electing successors in deadlocked companies, the potential for a dismissal suit (and related interim measures like suspension of duties) to offer a quicker way to remove a misbehaving "continuing rights" officer, and the argument that a full dismissal lawsuit provides a better opportunity for the officer in question to be heard on the merits of the allegations compared to the typically non-contentious procedure for appointing a temporary officer.

- Evaluation of the Supreme Court's Reasoning:

Some commentators have suggested that the Supreme Court's first and third stated reasons (that Article 854 doesn't explicitly mention "officers with continuing rights and duties," and therefore the law doesn't intend for such a suit) are somewhat formalistic. It could be argued that the term "officer" in Article 854 might be interpreted broadly enough to include individuals exercising identical rights and duties, or that Article 854 could be applied by analogy.

Thus, the most substantive and compelling reason provided by the Court is the second one: the existence and effectiveness of the alternative remedy through the appointment of a temporary officer under Article 346, Paragraph 2. - Due Process Considerations:

The affirmative view (favoring the dismissal suit) had raised concerns about the "continuing rights" officer's opportunity to be heard, suggesting a full lawsuit was more appropriate. However, the 2005 Companies Act (which was in effect at the time of this judgment, though the events leading to Z's status began under the old Commercial Code) included an important clarification in Article 346, Paragraph 1. It explicitly states that the "newly elected officer" whose assumption of office terminates the tenure of the "officer with continuing rights and duties" includes a temporary officer appointed under Paragraph 2. This was not as explicit in the old Commercial Code. This clarification significantly bolstered the argument that the legislature itself considers the temporary officer appointment process sufficient to oust a "continuing rights" officer, thereby weakening a key argument of the affirmative view. - Practical Efficiency:

Beyond strict statutory interpretation, practical considerations likely played a role. If a dismissal suit against a "continuing rights" director were allowed and succeeded, it would simply recreate a vacancy. In a deadlocked company like Company Y, electing a true successor would remain impossible. The only viable next step would then be to... petition for the appointment of a temporary officer. Thus, allowing a dismissal suit only to be followed by a temporary officer application would be a circuitous, time-consuming, and costly process. Petitioning directly for a temporary officer is a more straightforward and efficient path to removing a problematic "holdover" director. - A Potential Hurdle for the Dismissal Suit Route Anyway:

Even if Article 854 were deemed applicable, a common prerequisite for shareholders to bring such a suit is that a resolution to dismiss the officer in question must have first been put to a shareholders' meeting and rejected. In a 50/50 deadlocked company, it might be impossible to even get such a resolution formally rejected (or passed), potentially creating a practical barrier to using Article 854, a point some proponents of its applicability had themselves acknowledged. - The Unresolved Deadlock:

While the Supreme Court's decision clarifies the correct procedure for dealing with a misbehaving "director with continuing rights and duties," it does not, and cannot, resolve the underlying shareholder deadlock that prevents the appointment of a proper successor. For intractable situations like that in Company Y, more fundamental remedies, such as a negotiated share buyout between X and Z, or even a court-ordered dissolution of the company (under provisions like Article 471, Item 6 and Article 833, Paragraph 1, Item 1 of the Companies Act), might be the only ultimate solutions. - Conditions for Appointing a Temporary Officer:

Article 346, Paragraph 2 states that a temporary officer can be appointed when the court "deems it necessary." This is generally understood to apply when the "continuing rights" director is unsuitable for their role due to reasons like absence, prolonged illness, or, critically, misconduct. The Supreme Court's reasoning in this judgment suggests that a situation where an officer with continuing rights and duties has engaged in misconduct and a new officer cannot be elected due to deadlock would meet this "necessity" requirement. While some might argue this phrasing could be seen as adding a restrictive condition (requiring both misconduct and inability to elect), in practice, these two elements often coincide in the types of disputes where the appointment of a temporary officer to oust a "holdover" director is sought.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's February 26, 2008, judgment provides a clear directive: shareholders cannot use the statutory lawsuit for dismissal of an officer (Article 854) against an individual who is serving as an "officer with continuing rights and duties" under Article 346, Paragraph 1. Instead, the appropriate legal avenue for removing such an officer, particularly in cases of alleged misconduct where shareholder deadlock prevents the election of a successor, is to petition the court for the appointment of a "temporary officer" under Article 346, Paragraph 2. The appointment of this temporary officer will then terminate the tenure of the "officer with continuing rights and duties." This ruling emphasizes the specific statutory framework designed to handle such interim governance situations and directs aggrieved shareholders towards a more efficient, albeit different, remedial path.