Can Creditors Undo a Company Split? Japanese Supreme Court Affirms Avoidance Action for "Abusive Splits"

Judgment Date: October 12, 2012

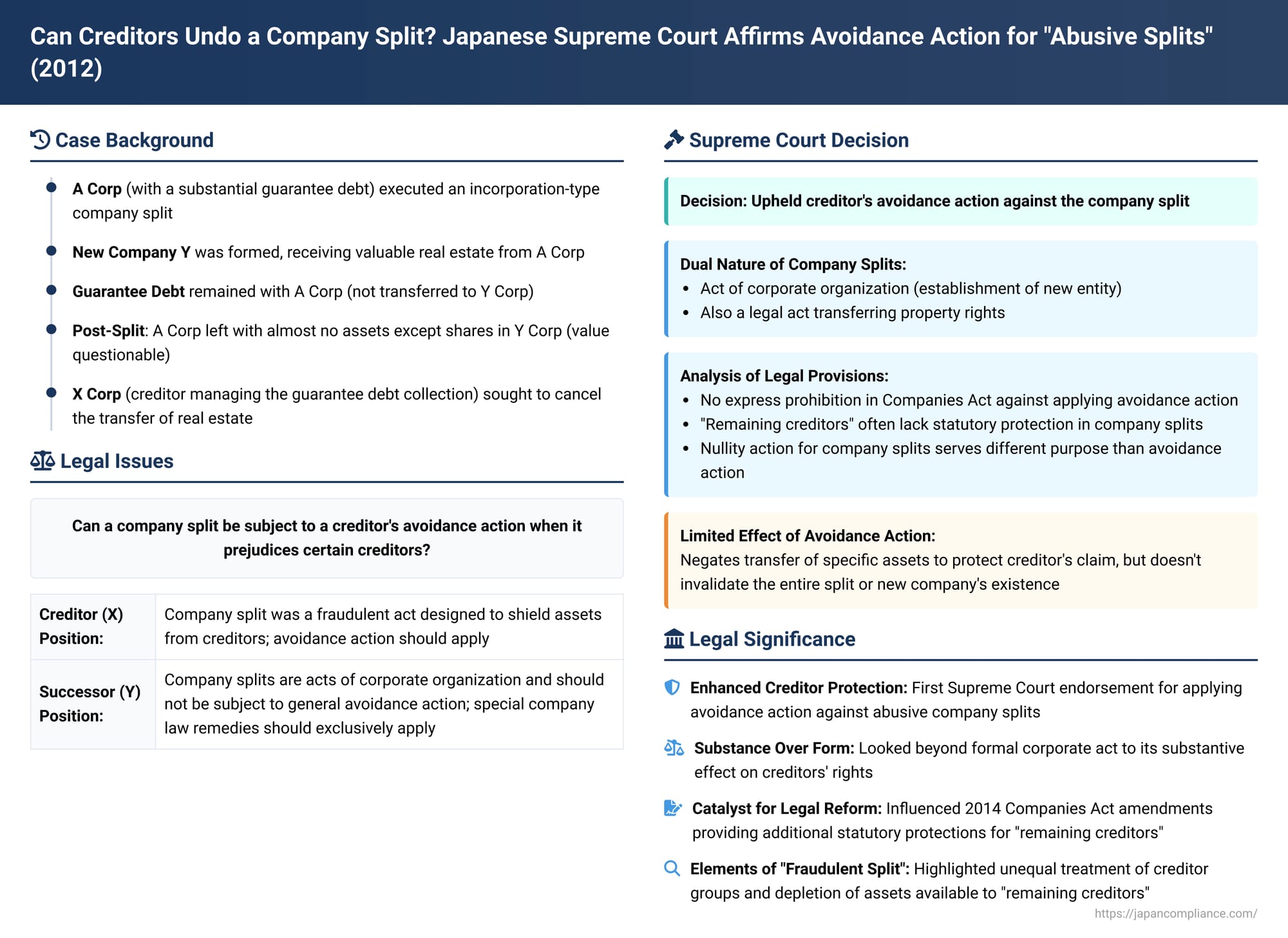

Company splits (会社分割 - kaisha bunkatsu), a form of corporate demerger or division in Japan, are versatile tools for restructuring businesses, allowing companies to separate and transfer parts of their operations to new or existing entities. While often used for legitimate strategic reasons, concerns have arisen about their potential misuse—specifically, "abusive company splits" designed to shield valuable assets from creditors by transferring them to a new entity while leaving significant debts with an effectively hollowed-out original company. A landmark 2012 Supreme Court of Japan decision addressed a critical question in this context: can such a company split be challenged and partially undone by a creditor using the general civil law remedy of a "creditor's avoidance action" (詐害行為取消権 - sagagai kōi torikeshi ken, akin to a fraudulent conveyance action)?

The Anatomy of the Disputed Company Split

The case involved A Corp, a company that was liable under a guarantee obligation ("the Guarantee Debt"). X Corp, a debt collection company (servicer), was entrusted with the management and collection of the claim related to this Guarantee Debt.

A Corp undertook an "incorporation-type company split" (shinsetsu bunkatsu), a process where a company carves out a portion of its business and transfers it to a newly established company.

- The Split: A Corp established a new entity, Y Corp. In this split, A Corp transferred certain rights and obligations, including specific valuable real estate ("the Real Estate"), to the newly formed Y Corp. In return for these assets, Y Corp issued all of its shares to A Corp.

- The Fate of the Guarantee Debt: Crucially, the substantial Guarantee Debt owed by A Corp (and managed by X Corp) was not among the liabilities transferred to Y Corp. This debt remained an obligation of A Corp. While some other debts of A Corp were transferred to Y Corp (with A Corp also providing a joint and several undertaking for those specific transferred debts), the Guarantee Debt was left behind.

- A Corp's Financial State Post-Split: At the time of the split, A Corp possessed no significant assets other than the Real Estate that could serve as security or a source of repayment for its debts. Following this split to Y Corp, and another incorporation-type split effected immediately thereafter (creating a B Corp), A Corp was left in a precarious financial position, holding virtually no assets apart from the shares it received in Y Corp and B Corp. These shares, given the circumstances, were likely of questionable and illiquid value.

The Creditor's Challenge: Alleging a Fraudulent Act

X Corp, faced with an asset-stripped A Corp still liable for the large Guarantee Debt, initiated legal proceedings against Y Corp (the recipient of the Real Estate). X Corp argued that A Corp's transfer of its primary asset, the Real Estate, to Y Corp through the company split constituted a fraudulent act detrimental to A Corp's creditors, particularly "remaining creditors" like X Corp whose debts were not assumed by the new, asset-rich entity.

X Corp sought the following remedies based on the creditor's avoidance action:

- The annulment (cancellation) of the portion of the company split agreement that pertained to the transfer of the Real Estate from A Corp to Y Corp.

- The cancellation of the registration of the ownership transfer of the Real Estate to Y Corp, which had been effected on the grounds of the company split.

The lower courts (Osaka District Court and Osaka High Court) both ruled in favor of X Corp, finding that the company split, in these circumstances, was indeed subject to the creditor's avoidance action. Y Corp appealed this decision to the Supreme Court. Y Corp's arguments included contentions that a company split, being an act of corporate organization, should not be subject to the general avoidance action, that doing so would conflict with the specific procedures in the Companies Act for challenging company splits (such as an action for nullity of the company split, which has strict standing requirements and short statutes of limitations), and that it would unfairly grant "remaining creditors" (those whose debts are not transferred) greater protection than "succeeding creditors" (those whose debts are transferred and who have statutory objection rights during the split process).

The Supreme Court's Landmark Decision

The Supreme Court, in its judgment dated October 12, 2012, dismissed Y Corp's appeal and upheld the lower courts' decisions, affirming that an incorporation-type company split can, under appropriate circumstances, be subject to a creditor's avoidance action.

The Court's reasoning was multi-layered:

- Dual Nature of Company Splits: The Supreme Court acknowledged that an incorporation-type company split is a complex legal act with a dual nature:

- It is undeniably an act concerning company organization, as it involves the establishment of a new corporate entity.

- Simultaneously, it is a legal act aimed at transferring property rights from the splitting company to the newly established company.

The Court reasoned that because a split involves the transfer of property rights, it cannot be automatically excluded from the scope of a creditor's avoidance action simply by virtue of also being an act of corporate organization. It cited a 1918 Daishin-in (pre-war Supreme Court) precedent where the formation of a company was subject to avoidance. However, the Court also cautioned that the organizational aspect means a split cannot automatically be presumed to be subject to avoidance either. A more detailed examination of the relevant provisions in the Companies Act and other laws is necessary.

- Analysis of Relevant Company Law Provisions:

- No Explicit Prohibition: The Court found that there are no express provisions in the Companies Act or other statutes that prohibit the application of the creditor's avoidance action to company splits.

- Need for Creditor Protection – The Gap for "Remaining Creditors": The Companies Act does provide certain creditor protection procedures for company splits (e.g., Article 810, allowing creditors whose debts are being transferred to the new company to object). However, the Court highlighted that "remaining creditors" – those creditors whose debts are not assumed by the newly established company and who can, in theory, still claim against the original splitting company – are generally not entitled to participate in these statutory objection procedures (unless specific exceptions apply, such as in a "split in which the splitting company is a human resource company" or certain other types of splits). For these remaining creditors, if they are harmed by the split (e.g., if the splitting company is left with insufficient assets), the creditor's avoidance action may be a necessary means of protection.

- Avoidance Action vs. Nullity Action for Company Splits: The Companies Act provides a specific, exclusive action for seeking the nullification of a company split (e.g., Article 828, Paragraph 1, Item 10). This action has strict requirements for standing and short time limits for filing, designed to ensure legal stability regarding the company's organization. Y Corp argued that allowing a general avoidance action would undermine this specific company law regime. However, the Supreme Court distinguished the two:

The effect of a creditor's avoidance action against a company split does not impact the validity of the new company's establishment itself. It targets the transfer of specific assets. An action for nullity, on the other hand, challenges the validity of the entire split, potentially affecting the existence of the new company. Given this difference in effect, the Court concluded that the existence of the nullity action does not preclude the application of the avoidance action when necessary for creditor protection.

- The Core Holding on Applicability of Avoidance Action:

Based on this reasoning, the Supreme Court held that:

In a case where an incorporation-type company split establishing a new stock company has occurred, a creditor of the original splitting company whose debt was not assumed by the newly established company, and who was also not entitled to object to the split under the statutory creditor protection procedures (i.e., a typical "remaining creditor"), can exercise the creditor's avoidance action pursuant to the provisions of the Civil Code (then-Article 424).

In such a case, the creditor can negate the legal effect of the transfer of rights (e.g., specific assets) to the newly established company, but only to the extent necessary for the preservation of their claim.

In essence, the split itself (and the new company's existence) remains valid, but the transfer of specific assets that prejudices the remaining creditor can be "clawed back" for the benefit of that creditor. In this particular case, it meant that the transfer of the Real Estate to Y Corp could be annulled to the extent needed to satisfy X Corp's claim against A Corp, and the property registration could be ordered to be reversed.

Justice Sudo's Concurring Opinion: The Unequal Impact on Creditors

Justice Masahiko Sudo, in a concurring opinion, further elaborated on the harm caused to creditors like X Corp. He pointed out that before the split, all of A Corp's general creditors (including those whose debts would later be transferred to Y Corp and those whose debts would remain with A Corp) had recourse to the entirety of A Corp's general assets, including the net value of the Real Estate. The company split fundamentally altered this:

- Remaining Creditors (like X Corp): Their pool of executable assets (the "security property") effectively shrank dramatically. They lost recourse to the Real Estate and were left primarily with a claim against A Corp, which now held only the (likely low-value and illiquid) shares of Y Corp and B Corp.

- Succeeding Creditors (whose debts were transferred to Y Corp): Their recourse effectively shifted to the assets transferred to Y Corp, including the Real Estate.

Justice Sudo noted that A Corp was already in a state of effective insolvency even before accounting for the large Guarantee Debt, with the Real Estate being its main valuable asset. Given that the Guarantee Debt was substantial, the shares A Corp received from Y Corp (capitalized at only ¥1 million) were likely worth very little compared to the lost value of the Real Estate as an asset available to X Corp. He described the situation metaphorically: a substantial asset of around ¥33 million (the Real Estate's net value) available to a large group of "remaining claims" was reduced to an asset of around ¥1 million, while a smaller group of "succeeding claims" continued to have recourse to that ¥33 million asset via Y Corp. This, he argued, resulted in a significant inequality between different classes of A Corp's original creditors.

Analysis and Implications

This 2012 Supreme Court decision was a landmark for creditor protection in the context of Japanese company splits:

- Affirmation of Avoidance Rights Against Abusive Splits: It provided the first clear Supreme Court endorsement for applying the general creditor's avoidance action to company splits designed to improperly shield assets from "remaining creditors." This was particularly important because the statutory creditor protection mechanisms in the Companies Act were often insufficient for these creditors.

- Focus on Substantive Harm, Not Just Corporate Form: The decision looks beyond the formal nature of a company split as an "organizational act" and focuses on its substantive effect as a transfer of property that can harm creditors.

- Limited Effect of Avoidance: The ruling carefully delineates the effect of the avoidance: it targets the asset transfer, not the existence of the new company. This maintains a degree of corporate stability while providing a remedy for the prejudiced creditor. The usual remedy under avoidance is restitution in kind (return of the specific asset), as affirmed here. However, if restitution in kind is impractical (e.g., assets are transformed or sold), monetary compensation is generally also a possibility, and the Supreme Court's ruling doesn't preclude this.

- Context of "Remaining Creditor" Vulnerability: The decision highlights the vulnerability of creditors whose debts are not transferred in a split, especially if the splitting company is left undercapitalized. They typically lack formal objection rights during the split process because, in theory, the splitting company receives shares of the new company as consideration, maintaining its net asset value. This theory often breaks down in abusive scenarios where the received shares are of little practical value.

- Impact of Subsequent 2014 Companies Act Amendments: In 2014, the Companies Act was amended to provide new protections for remaining creditors. For example, Article 764, Paragraph 4 now allows remaining creditors to make a direct claim against the successor company (up to the value of the assets it received) if the splitting company effected the split with the knowledge that it would harm these remaining creditors.

A question arose whether this new statutory remedy would supersede the general creditor's avoidance action. The prevailing view among commentators is that both remedies likely coexist. They have different aims (avoidance primarily seeks restoration of assets to the debtor's estate; the new direct claim provides a monetary claim against the successor) and different effects (e.g., avoidance can often be exercised by a bankruptcy trustee, while the direct claim might be personal to the creditor). The Supreme Court's 2012 reasoning, emphasizing the need for avoidance due to then-existing gaps in statutory protection, might be read in light of these subsequent amendments, but the distinct nature of the remedies suggests the avoidance action likely remains available. - Elements of a "Fraudulent" Split (Sagai-sei): The Supreme Court did not delve into the specific elements constituting the "fraudulent act" in this case, as that was not the focus of the appeal. Following 2017 amendments to the Civil Code's provisions on avoidance actions (which now categorize different types of voidable acts, similar to bankruptcy law), how an abusive company split fits into these categories (e.g., an act reducing the debtor's total assets, an act where equivalent consideration is received but is harder for creditors to reach, or an act that is effectively a preference for certain creditors) is a subject of ongoing legal analysis. Justice Sudo's opinion, focusing on the unequal treatment of creditor groups, leans towards viewing the split as having a preferential effect.

Conclusion

The October 12, 2012, Supreme Court decision firmly established that company splits, despite their nature as acts of corporate organization, are not immune from the creditor's avoidance action (fraudulent conveyance claims). When a company structures a split in such a way that valuable assets are transferred to a new entity while significant liabilities are left with the original, now asset-depleted, company, and "remaining creditors" are prejudiced without adequate statutory means to object, those creditors can seek to annul the asset transfer to the extent necessary to protect their claims. This ruling significantly bolstered creditor protection against abusive company restructurings in Japan, emphasizing substance over form and providing a crucial remedy where specific company law protections were found wanting.