Can Creditors Sue a Debtor Company Under a Payment Prohibition Order? A 1962 Japanese Supreme Court Ruling

Date of Judgment (A4): March 23, 1962 (Showa 37)

Case Name (A4): Claim for Payment on Promissory Note

Court (A4): Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench

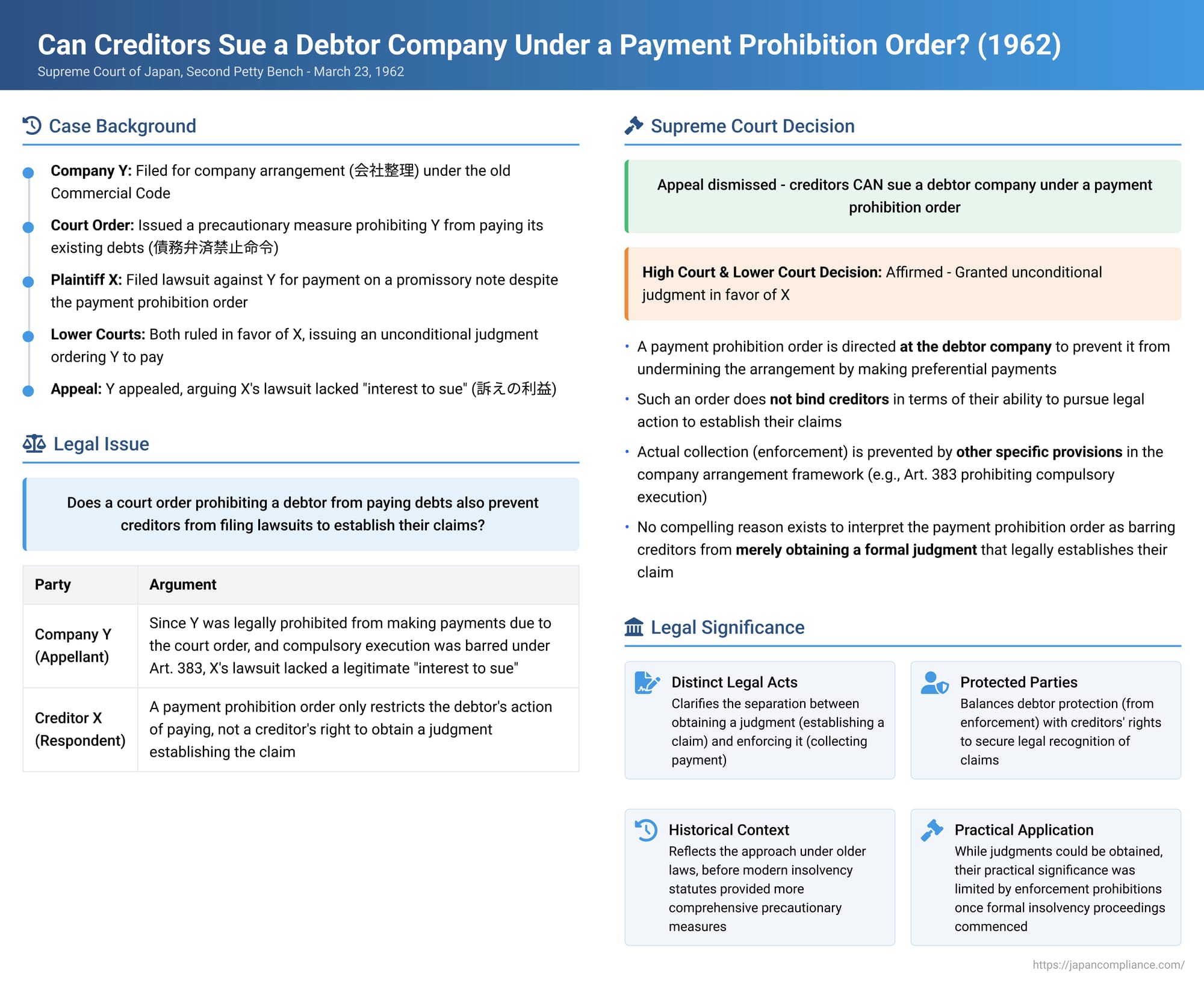

This blog post delves into a 1962 Supreme Court of Japan decision (referred to as A4 based on the provided source material). The case addressed a fundamental question in pre-insolvency situations: if a company is subject to a court-ordered precautionary measure prohibiting it from paying its debts, can a creditor still initiate a lawsuit against that company to obtain a formal judgment for payment?

Facts of the Case (A4)

The plaintiff, X (respondent before the Supreme Court), was the holder of a promissory note issued by company Y (appellant before the Supreme Court). X filed a lawsuit demanding payment from Y based on this promissory note.

Prior to X initiating this suit, Y had already filed for "company arrangement" (会社整理 - kaisha seiri), an older form of corporate restructuring procedure under the Japanese Commercial Code. In connection with Y's application for company arrangement, the court had issued a precautionary measure (保全処分 - hozen shobun) specifically prohibiting Y from making payments on its existing debts (a "debt payment prohibition order" - 債務弁済禁止命令, under Article 386, Paragraph 1, Item 1 of the old Commercial Code, a provision now deleted). Subsequently, Y's company arrangement proceedings had formally commenced.

Despite the payment prohibition order, both the court of first instance and the appellate court (second instance) ruled in favor of X, issuing an unconditional judgment ordering Y to pay the amount due on the promissory note. Y appealed this decision to the Supreme Court. Y's main argument was that since it was legally prohibited from making payments due to the court order, and because compulsory execution against its assets was also barred under the company arrangement provisions (old Commercial Code Art. 383), X's lawsuit lacked a legitimate "interest to sue" (訴えの利益 - uttae no rieki).

The Supreme Court's Decision (A4)

The Supreme Court dismissed Y's appeal, affirming the lower courts' decisions to grant the payment judgment to X .

The Court's reasoning was as follows:

- Purpose and Scope of the Payment Prohibition Order:

The Supreme Court clarified that a precautionary order prohibiting debt payment, issued under provisions like Article 386, Paragraph 1, Item 1 of the old Commercial Code in the context of company arrangement proceedings, is primarily directed at the company as the debtor. Its purpose is to prevent the company from acting in a way that would undermine the objectives of the arrangement, for example, by making preferential payments to certain creditors while neglecting others. - Order Does Not Directly Bind Creditors' Right to Sue:

Crucially, such a payment prohibition order does not directly bind the company's creditors in terms of their ability to pursue legal action to establish their claims. It does not strip them of the right to file a lawsuit and obtain a title of indebtedness (such as a court judgment) against the company. - Prevention of Actual Collection Handled by Other Provisions:

The Court noted that the actual collection of debts by creditors (e.g., through enforcement measures) is sufficiently prevented by other specific provisions within the company arrangement framework, such as Article 383 of the old Commercial Code, which explicitly prohibited compulsory execution, provisional attachment, or provisional disposition against the company's assets once arrangement proceedings were underway. - No Grounds to Prohibit Obtaining a Judgment:

Given that the payment prohibition order is aimed at the debtor's actions (making payments) and that separate provisions prevent creditors from enforcing claims, there is no compelling reason to interpret the payment prohibition order itself as also barring creditors from merely obtaining a formal judgment that legally establishes their claim and its amount.

Therefore, the Supreme Court concluded that the lower courts did not err in law by granting an unconditional judgment for payment in favor of X, even though Y was subject to a debt payment prohibition order.

Commentary and Elaboration

1. Context: Precautionary Measures in Insolvency Proceedings

Before formal insolvency proceedings (like bankruptcy, civil rehabilitation, or corporate reorganization) are officially commenced, there is often a critical "gap" period. During this period, there's a risk that the financially distressed debtor might try to dissipate assets, make preferential payments to favored creditors, or otherwise act in a way that harms the collective body of creditors. To mitigate these risks, Japanese insolvency laws allow courts to issue various "precautionary measures" (保全処分 - hozen shobun) upon or after the filing of an insolvency petition but before the main proceedings start (e.g., Bankruptcy Act Article 28, Paragraph 1; Civil Rehabilitation Act Article 30, Paragraph 1; Corporate Reorganization Act Article 28, Paragraph 1). A common and important precautionary measure is an order prohibiting the debtor from making payments on existing debts, as was issued in the A4 case.

2. The Target and Effect of a Debt Payment Prohibition Order

The prevailing legal understanding, with which the Supreme Court's decision in A4 aligns, is that a debt payment prohibition order is primarily addressed to the debtor. It restricts the debtor's capacity to dispose of assets by making payments. It does not, in itself, extinguish the creditor's underlying claim, nor does it directly strip creditors of their right to take legal steps to have their claim recognized, such as filing a lawsuit and pursuing it to judgment. The primary aim is to freeze the debtor's payment activities to preserve the status quo for the benefit of a potential future collective proceeding.

3. Limited Practical Significance of Obtaining a Judgment Under Such an Order

While the Supreme Court in A4 affirmed the legality of a creditor obtaining a payment judgment against a debtor under a payment prohibition order, the commentary points out that the practical significance of such a judgment can be limited, especially once formal insolvency proceedings commence. This is because:

- Stay of Enforcement: Upon the commencement of formal insolvency proceedings, new attempts at compulsory execution by individual creditors are typically prohibited (e.g., Bankruptcy Act Article 42, Paragraph 1; Civil Rehabilitation Act Article 39, Paragraph 1; Corporate Reorganization Act Article 50).

- Suspension of Litigation: Pending lawsuits against the debtor are often suspended (e.g., Bankruptcy Act Article 44; Civil Rehabilitation Act Article 40; Corporate Reorganization Act Article 52).

- Lapse of Existing Enforcement: Even enforcement actions already underway might be stayed or lose their effect against the debtor's estate.

So, while a creditor might obtain a judgment, their ability to individually enforce it and collect the debt is severely curtailed or eliminated once formal insolvency proceedings are in full swing. The claim generally must then be dealt with within the collective insolvency process.

4. Modern Insolvency Law and More Comprehensive Protective Measures

The commentary notes that current Japanese insolvency laws provide a more comprehensive toolkit for managing creditor actions and protecting the debtor's estate, even in the period leading up to the formal commencement of proceedings. Beyond simple payment prohibition orders, courts can issue:

- Specific Stay Orders: These can halt ongoing litigation, compulsory execution procedures, provisional attachments, or provisional dispositions (e.g., Bankruptcy Act Article 24, Paragraph 1, Items 1 & 3; Civil Rehabilitation Act Article 26, Paragraph 1, Items 2 & 3; Corporate Reorganization Act Article 24, Paragraph 1, Items 2 & 4).

- Comprehensive Prohibition Orders: These are broad injunctions that can forbid all creditors from engaging in execution, attachments, etc., against the debtor's property, effectively creating a more complete "freeze" (e.g., Bankruptcy Act Article 25, Paragraph 1; Civil Rehabilitation Act Article 27, Paragraph 1; Corporate Reorganization Act Article 25, Paragraph 1).

These modern tools can be used proactively to prevent a "race to the courthouse" by creditors and to stop them from obtaining judgments or levying execution even before a formal bankruptcy, rehabilitation, or reorganization order is issued. This contrasts with the older framework where the primary shield against enforcement often only became fully effective upon the formal commencement of proceedings, as highlighted by the A4 case's focus on the effect of the payment prohibition itself versus the separate execution prohibition.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 1962 decision in case A4 established an important principle under the then-existing legal framework: a court order merely prohibiting a debtor company from making payments as a precautionary measure during company arrangement proceedings did not, in itself, prevent creditors from suing that company to establish the validity and amount of their claims and obtain a formal judgment. The Court distinguished between the debtor's obligation not to pay and the creditor's right to seek legal recognition of a debt. While the practical ability to enforce such a judgment would be significantly limited by other insolvency rules, the right to obtain the judgment itself was upheld. This ruling reflects a specific balance struck under older commercial laws. Modern Japanese insolvency statutes now offer a more extensive array of precautionary measures to manage creditor actions and preserve the debtor's estate comprehensively from the early stages of financial distress.