Can Creditors Pursue Fraudulent Conveyance Claims After a Debtor's Bankruptcy Discharge?

Date of Judgment: February 25, 1997 (Heisei 9)

Case Name: Claim for Avoidance of Fraudulent Act, etc.

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench

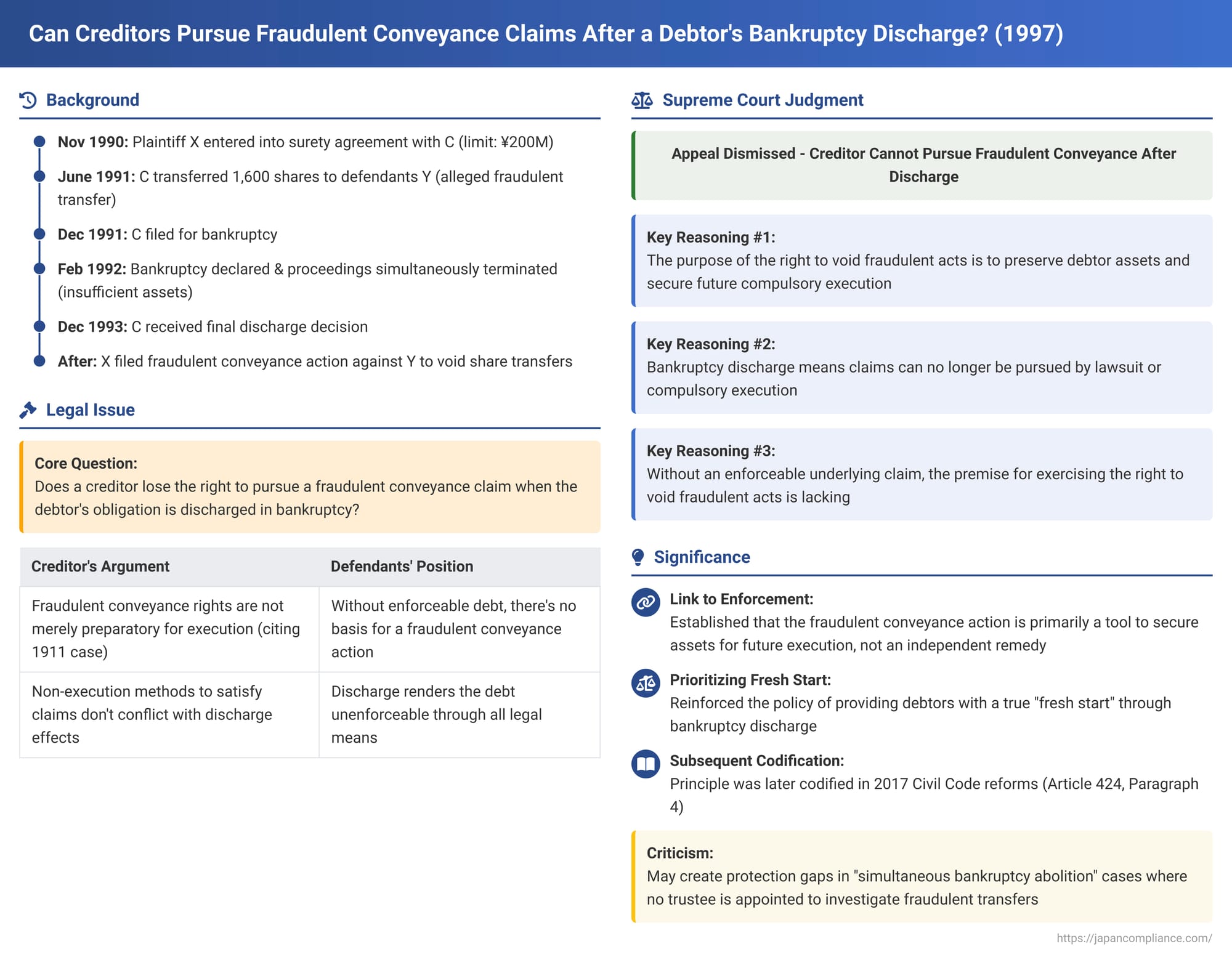

This blog post delves into a 1997 Supreme Court of Japan decision that addressed a significant question at the intersection of bankruptcy discharge and creditor remedies: if a debtor receives a discharge from their debts in bankruptcy, can a creditor whose claim has been discharged still exercise the right to void a fraudulent transfer of assets made by the debtor before the bankruptcy?

Facts of the Case

The plaintiff, X (appellant before the Supreme Court), was a creditor. On November 30, 1990, X entered into a basic transaction agreement with company A and its representative director, B. Concurrently, X entered into a continuing suretyship agreement with C, where C guaranteed the debts arising from A's transactions with X, up to a limit of 200 million yen. As of June 1991, X held a claim of 200 million yen against C under this suretyship agreement.

On December 11, 1991, C filed for personal bankruptcy. On February 17, 1992, C received a bankruptcy declaration (破産宣告 - hasan senkoku, now bankruptcy commencement decision) and, simultaneously, a decision for the abolition of bankruptcy proceedings (同時破産廃止決定 - dōji hasan haishi kettei, often issued when there are insufficient assets for distribution). Subsequently, C applied for and was granted a discharge decision (免責決定 - menseki kettei) on December 7, 1993, which became final and conclusive.

The core of X's claim was that in June 1991 (before C's bankruptcy filing), C, knowing it would harm X as a creditor, transferred a total of 1600 shares in D Co., Ltd. (which C owned) to Y1 through Y6 (the defendants/appellees, collectively "Y") at an unjustly low price. X filed a lawsuit against Y, seeking the avoidance (cancellation) of these share transfer agreements based on the creditor's right to void fraudulent acts (詐害行為取消権 - saghai kōi torikeshi-ken, similar to a fraudulent conveyance action) and demanding the return of the share certificates or payment of their equivalent monetary value. C's discharge decision became final while X's lawsuit against Y was pending in the first instance court.

Lower Court Rulings

The Tokyo District Court (court of first instance) dismissed X's claim. X appealed. The Tokyo High Court (appellate court) also dismissed the appeal, reasoning that since a debt for which a debtor has received a bankruptcy discharge cannot be enforced through compulsory execution, the right to void a fraudulent act—which serves as a preparatory step for such execution—also cannot be exercised.

X appealed to the Supreme Court, arguing, among other things, that established case law (dating back to a Daishin-in (Great Court of Cassation) judgment of Meiji 44 (1911).3.24) did not position the right to void fraudulent acts merely as a preparatory step for compulsory execution, and that satisfying a claim through means other than compulsory execution does not conflict with the effect of a bankruptcy discharge.

The Supreme Court's Decision

The Supreme Court dismissed X's appeal .

The Court reasoned as follows:

- The creditor's right to void a fraudulent act is a right granted to creditors to preserve the debtor's assets (which would otherwise be available to satisfy debts) and to secure future compulsory execution .

- In this case, C (the guarantor debtor) had received a final and conclusive discharge decision under the Bankruptcy Act for the suretyship debt owed to X .

- As a result of this discharge, X's right to claim performance of the suretyship obligation from C could no longer be pursued by lawsuit, nor could its compulsory realization be sought (referencing Article 366-12 of the old Bankruptcy Act, equivalent to current Article 253) .

- Consequently, the premise for exercising the right to void a fraudulent act—an enforceable underlying claim—was now lacking .

- Therefore, X could not exercise the right to void fraudulent acts with respect to asset dispositions C made before filing for bankruptcy, based on the now-discharged suretyship claim .

The Supreme Court found the High Court's judgment, which reached the same conclusion, to be justifiable and affirmed it. The Court also stated that its decision did not conflict with the precedents cited by X and that there was no illegality in the High Court's judgment .

Commentary and Elaboration

1. Significance of the Decision

This Supreme Court decision established that once a debtor's bankruptcy discharge becomes final, a creditor whose claim was subject to that discharge cannot subsequently exercise the creditor's right to void a fraudulent act (a fraudulent conveyance action) using that discharged claim as the underlying protected interest. This conclusion is derived from two interconnected legal understandings:

- The effect of a bankruptcy discharge: It makes the discharged debt unenforceable through compulsory execution.

- The purpose of the fraudulent conveyance action: It is primarily a tool to secure assets for future compulsory execution.

2. The Effect of Bankruptcy Discharge

- The bankruptcy discharge system was introduced into Japanese law in 1952 to enable the economic rehabilitation of individual bankrupts. Article 366-12 of the old Bankruptcy Act (the provision applicable in this case, with similar content now in Article 253, Paragraph 1 of the current Bankruptcy Act) defined the effect of discharge.

- There have been several interpretations of this effect:

- Liability Extinguishment Theory (責任消滅説 - sekinin shōmetsu-setsu) / Natural Obligation Theory (自然債務説 - shizen saimu-setsu): This has been the prevailing view. It posits that discharge extinguishes only the debtor's liability for the debt, while the debt itself continues to exist as a "natural obligation." This interpretation allows for the debtor to make voluntary repayments on the discharged debt if they choose to do so.

- Debt Extinguishment Theory (債務消滅説 - saimu shōmetsu-setsu): An influential opposing view argues that the debt itself is extinguished by the discharge. This would logically preclude voluntary repayment, as no debt remains. (The practical differences in outcomes between these two theories are often considered minor).

- Debtor Extinguishment Theory (主体消滅説 - shutai shōmetsu-setsu): Another theory, aiming for consistency with situations where a corporate debtor is dissolved after bankruptcy, suggests that a discharged debt becomes a "debt without a debtor."

- The Supreme Court's wording in the present judgment (and in subsequent related rulings) appears more aligned with the prevailing "liability extinguishment" theory.

- Regardless of these theoretical distinctions, there is broad academic consensus that a discharged bankruptcy claim cannot be enforced through legal action or compulsory execution. In this respect, the Supreme Court's understanding of the effect of discharge in this case was uncontroversial.

3. The Purpose of the Fraudulent Conveyance Action

- The creditor's right to void fraudulent acts was historically governed by Articles 424 to 426 of the old Civil Code (prior to the 2017 reforms), supplemented by a body of case law, including a landmark Daishin-in judgment from 1911.

- This case law was characterized by:

- The "eclectic theory," allowing a creditor to simultaneously seek the voiding of the fraudulent act and the restitution of the improperly transferred property.

- The "relative effect" of voiding, meaning the cancellation of the fraudulent act is effective only between the voiding creditor and the transferee of the asset, not erga omnes.

- While academic views on the precise nature of this right varied, most scholars, regardless of their support for the specific case law doctrines, agreed that the fundamental purpose of the fraudulent conveyance action was to preserve or recover assets for the ultimate purpose of satisfying the creditor's claim through subsequent compulsory execution.

- Some older case law had permitted creditors exercising this right to demand direct payment of the value of the avoided assets to themselves, which could result in a de facto priority payment over other creditors. This led some scholars to theorize the fraudulent conveyance action as a debt collection mechanism independent of compulsory execution.

- The appellant X in this case emphasized this potential for direct recovery. However, the Supreme Court in this 1997 judgment reaffirmed the traditional position that the fraudulent conveyance action is primarily a means to prepare for or facilitate future compulsory execution. The Court noted that prior case law had not explicitly endorsed a de facto priority recovery by the voiding creditor.

- Subsequent Civil Code Reform (2017): The 2017 amendments to the Civil Code codified this understanding. The new Article 424, Paragraph 4 explicitly states that a creditor cannot exercise the right to void a fraudulent act with respect to a claim that cannot be realized through compulsory execution. This legislative change aligns directly with the conclusion reached by the Supreme Court in the present case.

4. Concerns Regarding Creditor Protection

The Supreme Court's decision has faced criticism, particularly from the perspective of creditor protection, especially in "simultaneous bankruptcy abolition" (dōji haishi) cases.

- In dōji haishi cases, a bankruptcy trustee is not appointed, usually because the debtor lacks sufficient assets to cover the costs of bankruptcy administration. The argument is that if a trustee were appointed, they would investigate the debtor's pre-bankruptcy conduct, potentially uncover fraudulent transfers, and exercise the trustee's strong avoidance powers (否認権 - hinin-ken). The trustee might also find grounds to object to the debtor's discharge. In a dōji haishi scenario, these creditor-protective mechanisms, typically wielded by a trustee, are absent.

- Critics argued that allowing individual creditors to pursue fraudulent conveyance actions even after a discharge (especially in dōji haishi cases) could serve as a necessary compensatory measure for this lack of trustee action.

- Countervailing Trends and Existing Mechanisms:

- In practice, there has been a trend towards appointing trustees even in cases with relatively small assets, through procedures like "small-sum trusteeship" (少額管財 - shōgaku kanzai), which can help address this concern by ensuring some level of investigation.

- Furthermore, if a debtor's fraudulent acts are discovered after a discharge decision has become final (though this was not the fact pattern in the present case), the Bankruptcy Act itself provides a remedy: if the bankrupt is subsequently convicted of a bankruptcy crime like fraudulent bankruptcy (Bankruptcy Act Article 265), the discharge decision can be revoked (Bankruptcy Act Article 254, Paragraph 1), causing the original discharge to lose its effect (Article 254, Paragraph 5). The adequacy of these existing mechanisms is ultimately a matter for legislative policy.

- Allowing post-discharge fraudulent conveyance actions, as suggested by critics, would also raise fundamental questions about whether doing so would undermine the rehabilitative purpose of the bankruptcy discharge system.

5. Scope of the Judgment (Extrapolation)

The reasoning in this Supreme Court decision is likely to have broader implications:

- Rehabilitative Proceedings: Similar conclusions might be reached regarding the effect of discharge in rehabilitative insolvency proceedings, such as Civil Rehabilitation (Civil Rehabilitation Act Article 178, Paragraph 1) and Corporate Reorganization (Corporate Reorganization Act Article 204, Paragraph 1), which also render covered claims unenforceable through compulsory execution.

- Creditor's Subrogation Right: The reasoning could also extend to the creditor's subrogation right (債権者代位権 - saikensha daii-ken under Civil Code Article 423), which, like the fraudulent conveyance action, is generally viewed as a means to preserve assets for future execution. The revised Civil Code (Article 423, Paragraph 3) now also links the exercise of subrogation to the enforceability of the underlying claim. A 2008 Tokyo High Court decision has also touched upon this in a similar vein.

Conclusion

The 1997 Supreme Court decision firmly established that a creditor cannot pursue a fraudulent conveyance action based on a debt that has been discharged in the debtor's bankruptcy. The Court anchored this conclusion in the understanding that the primary purpose of a fraudulent conveyance action is to secure assets for compulsory execution, a process that is no longer available for a discharged debt. While this ruling provides legal certainty, it also highlights the ongoing tension between facilitating a debtor's fresh start through discharge and ensuring adequate remedies for creditors, particularly in situations involving pre-bankruptcy misconduct. Subsequent legislative reforms have largely codified the principle set forth in this judgment.