Can an Estate Division Agreement Be Undone Due to Broken Promises? A Japanese Supreme Court Ruling

Date of Judgment: February 9, 1989 (Heisei 1)

Case: Supreme Court of Japan, First Petty Bench, Case No. Showa 59 (o) No. 717 (Claim for Correction of Registration Procedure, etc.)

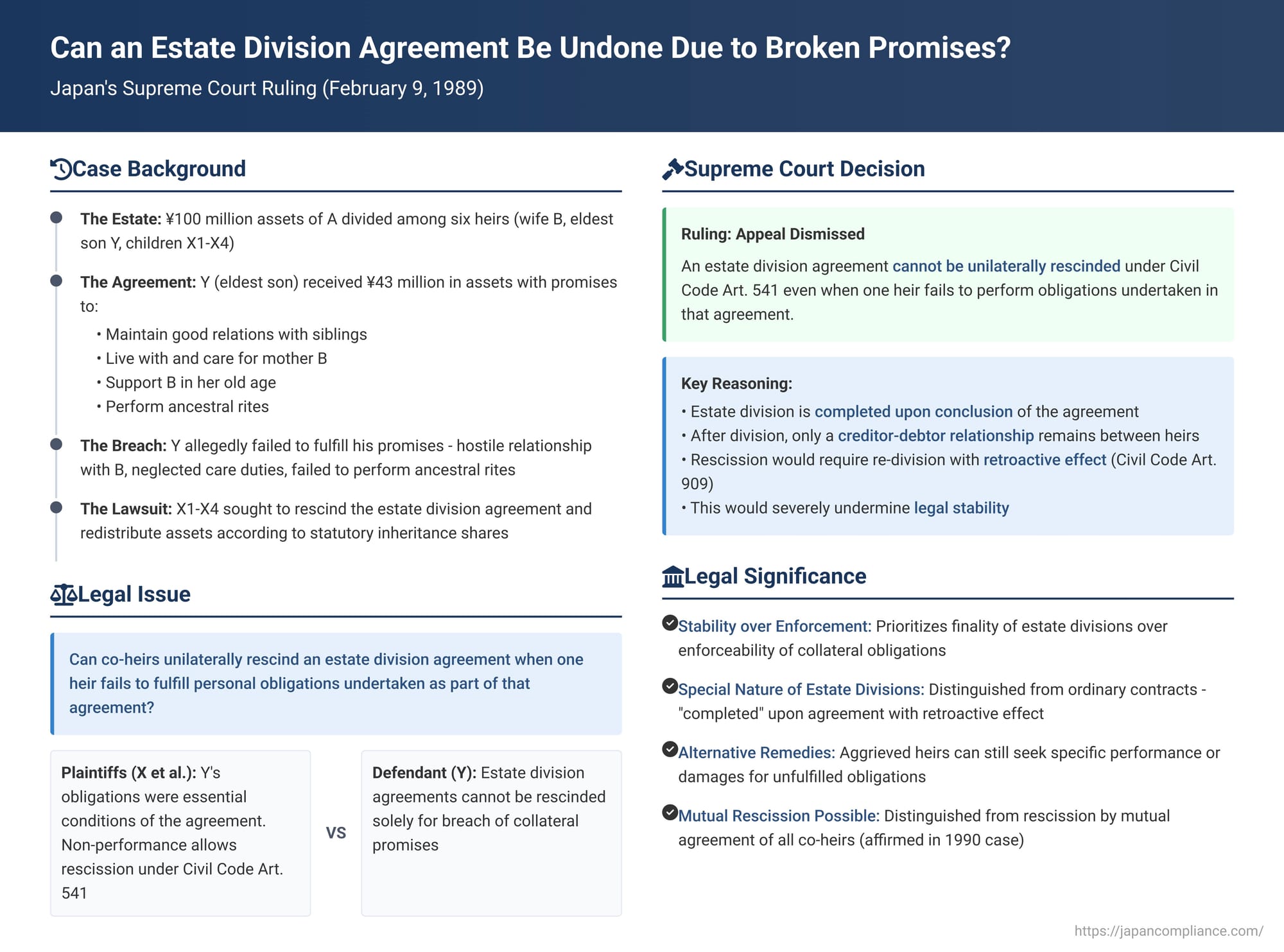

Estate division agreements (遺産分割協議 - isan bunkatsu kyōgi) among co-heirs are pivotal in settling the distribution of a deceased person's assets. These agreements can be complex, often involving not just the allocation of properties but also commitments by one or more heirs to undertake certain actions or responsibilities. But what happens if an heir fails to live up to these promises? Can the other heirs unilaterally rescind the entire estate division agreement due to this breach? The Supreme Court of Japan addressed this critical question in its decision on February 9, 1989, emphasizing the finality of such agreements.

Facts of the Case: A Division Agreement with Personal Undertakings

The case involved the estate of A and a subsequent dispute among his six legal heirs:

- B: A's wife (one of the original plaintiffs, who passed away during the first instance proceedings; her statutory inheritance share was 1/3).

- Y: A's eldest son (the defendant/appellee, who passed away after the High Court judgment).

- X1, X2, X3, X4: A's eldest daughter, second daughter, second son, and third son, respectively (plaintiffs/appellants; each child's statutory inheritance share was 2/15).

The total value of A's estate was approximately ¥100 million. An estate division agreement was reached among the six heirs with the following distribution:

- B (wife) was to receive assets worth approximately ¥38 million (about 1/3 of the estate), including the main family house, its land, and rental properties.

- Y (eldest son) was to receive the largest portion, assets worth approximately ¥43 million, including land and factory buildings.

- X3 and X4 (other sons) were each to receive assets (land, factory, etc.) worth approximately ¥14.7 million, with adjustments made for lifetime gifts they had already received.

In addition to this allocation of assets, the six heirs also agreed that Y (the eldest son) would undertake four specific personal commitments:

- To maintain amicable and brotherly relations with X3 and X4.

- To live with his mother, B.

- To support B, provide for her personal care in a manner that would satisfy her, and make his utmost efforts to ensure she could live out her old age comfortably and fittingly.

- To succeed to the family's ancestral rites and diligently perform all related ceremonies.

Y's Alleged Breach of Undertakings:

Following the agreement, relationships within the family deteriorated.

- Y's relationship with his brothers X3 and X4 soured due to business disagreements.

- Although Y did live with B, their cohabitation became hostile. It was alleged that Y refused to prepare B's meals, had her health insurance coverage terminated, and even physically assaulted her.

- Y also reportedly neglected the performance of ancestral rites, including memorial services for A, which B consequently had to manage herself.

The Plaintiffs' Claim and Lower Court Rulings:

The other siblings (X1-X4, hereinafter "X et al.") asserted that Y's four undertakings were essential and conditional parts of the estate division agreement. They argued that Y’s failure to fulfill these undertakings constituted a fundamental breach of obligations he had accepted as part of the overall estate settlement.

Consequently, X et al. declared the entire estate division agreement (or at least those parts of it that constituted a gift with burdens to Y) to be rescinded due to Y's non-performance. They then filed a lawsuit against Y, demanding that the registration of the properties Y had acquired through the estate division be corrected to reflect ownership according to the heirs' statutory inheritance shares, effectively seeking to nullify the agreed-upon division.

Both the Kyoto District Court (first instance) and the Osaka High Court (on appeal) dismissed the claims of X et al.. These lower courts found that the evidence did not establish that Y's four undertakings were agreed upon as legal conditions for the validity or continuation of the estate division. More fundamentally, both courts held that an estate division agreement, by its inherent nature, cannot be unilaterally rescinded by some heirs due to another heir's failure to perform an obligation undertaken within that agreement. They concluded that the general contract law principle allowing for rescission due to non-performance (Article 541 of the Civil Code) does not apply to estate division agreements.

X et al. appealed this decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Decision: Upholding the Stability of Estate Divisions

The Supreme Court dismissed the appeal by X et al., thereby affirming the lower courts' conclusion that the estate division agreement could not be unilaterally rescinded.

The Court's core reasoning was as follows:

"When an estate division agreement has been concluded among co-heirs, even if one heir fails to perform an obligation towards another heir that was undertaken in said agreement, the other heirs cannot rescind the said estate division agreement under Article 541 of the Civil Code. This is because, by its nature, an estate division is completed upon the conclusion of the agreement, and thereafter, what remains is merely a creditor-debtor relationship between the heir who undertook the obligation in the said agreement and the heir who acquired the right to that performance. Moreover, if this interpretation were not adopted, a re-division of the estate, which has retroactive effect under Article 909, main clause, of the Civil Code, would be necessitated, and legal stability would be severely undermined."

Legal Principles and Significance

This 1989 Supreme Court decision is a landmark ruling that clarifies the legal nature and robustness of estate division agreements in Japan.

- Rejection of Unilateral Rescission for Non-Performance: This was the Supreme Court's first explicit pronouncement on this specific issue. It firmly established that estate division agreements are not subject to unilateral rescission by some heirs based on another heir's failure to fulfill collateral obligations undertaken as part of the division, even if those obligations were significant to the overall family settlement. This aligned with the consistent position previously taken by lower courts.

- Why Estate Division Agreements Are Distinct from Ordinary Contracts in This Regard:

- Completion Upon Agreement: The Supreme Court views an estate division as being legally "completed" or "finished" the moment the heirs reach an agreement on the allocation of assets. Any personal obligations undertaken by heirs as part of that agreement (e.g., Y's promises regarding family relations or care for B) are seen as subsequent, individual rights and duties that arise between specific heirs, rather than as ongoing conditions for the validity of the division itself. The primary purpose of the "agreement"—the division of the estate assets—is achieved at its conclusion.

- Overriding Concern for Legal Stability: A crucial factor in the Court's reasoning is the profound importance of legal stability. Estate division has a retroactive effect (遡及効 - sokyūkō) under Article 909 of the Civil Code, meaning that once a division is made, the heirs are deemed to have acquired their specific assets directly from the deceased at the time of death. If such an agreement could be unilaterally rescinded due to a subsequent breach of a collateral promise, it would force a complete re-division of the estate, retroactively unsettling property rights and creating significant legal uncertainty. This was deemed too disruptive.

- Nature of the Estate Division Agreement Itself: Legal commentary explores various theoretical underpinnings for this stance. Historically, one argument against applying general rescission rules was that estate division agreements might not always fit the mold of typical bilateral contracts with strictly reciprocal obligations, which Article 541 was traditionally seen as primarily addressing. While the Supreme Court in this case did not lean heavily on the "lack of reciprocity" argument, its focus on the special character of estate division—particularly its "declaratory" nature (宣言主義 - sengen-shugi, meaning it declares pre-existing rights rather than creating new ones) and the impact of retroactivity—achieves a similar result of treating it as distinct.

- Alternative Remedies for Aggrieved Heirs: If unilateral rescission of the entire division agreement is off the table, what recourse do heirs have when another heir defaults on obligations undertaken in that agreement?

- They can sue for specific performance of the obligation, if the nature of the obligation allows for it (though many of Y's undertakings in this case were highly personal and arguably not amenable to specific performance).

- They can sue for monetary damages resulting from the non-performance of the obligation.

- The PDF commentary also notes that if an obligation undertaken by an heir is considered part of a "gift with a burden" (負担付贈与 - futan-tsuki zōyo) made within the context of the estate division, specific legal rules might allow for the rescission of that particular gift component between the direct parties to it (the donor-heir and the donee-heir who accepted the burden). However, this would typically not lead to the unraveling of the entire multi-party estate division agreement.

- Important Distinction: Rescission by Mutual Agreement (合意解除 - Gōi Kaijo):

It is crucial to distinguish the unilateral rescission addressed in this 1989 judgment from rescission by mutual agreement of all co-heirs. This Supreme Court ruling does not prevent all co-heirs from unanimously agreeing to set aside a previous estate division agreement and conduct a new one. Indeed, the Supreme Court explicitly affirmed the permissibility of rescission by mutual agreement (and subsequent re-division) in a later decision (Heisei 2.9.27 - September 27, 1990). The key difference is that mutual consent by all parties can adequately address concerns about legal stability, particularly if a new, superseding agreement is established concurrently. - Nature of Collateral Undertakings: In this particular case, Y's undertakings were deeply intertwined with family relationships, personal care, and traditional duties. The legal commentary acknowledges a broader debate about whether such highly personal and often difficult-to-enforce commitments should be treated as standard "legal obligations" whose breach triggers conventional contract remedies, or whether they are more in the realm of moral or ethical commitments, especially when a primary motivation for the estate distribution might have been to entrust these very duties to a specific heir.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 1989 decision strongly prioritizes the legal stability and finality of concluded estate division agreements. It establishes that such agreements cannot be unilaterally undone by some heirs merely because another heir fails to perform personal or financial obligations undertaken as part of the overall settlement. While heirs who are victims of such breaches are not left without remedy (they can pursue claims for specific performance or damages relating to the unfulfilled obligation), the core division of the estate assets, once agreed upon, remains intact. This ruling underscores the unique nature of estate division as a process that, upon agreement, is deemed concluded, with subsequent obligations creating separate interpersonal legal claims rather than grounds for unwinding the entire asset allocation. This principle is vital for ensuring predictability and security in the often complex aftermath of inheritance.