Can a Company Unilaterally Cut a Director's Pay? A 1992 Japanese Supreme Court Ruling

Date of Judgment: December 18, 1992

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench

Introduction

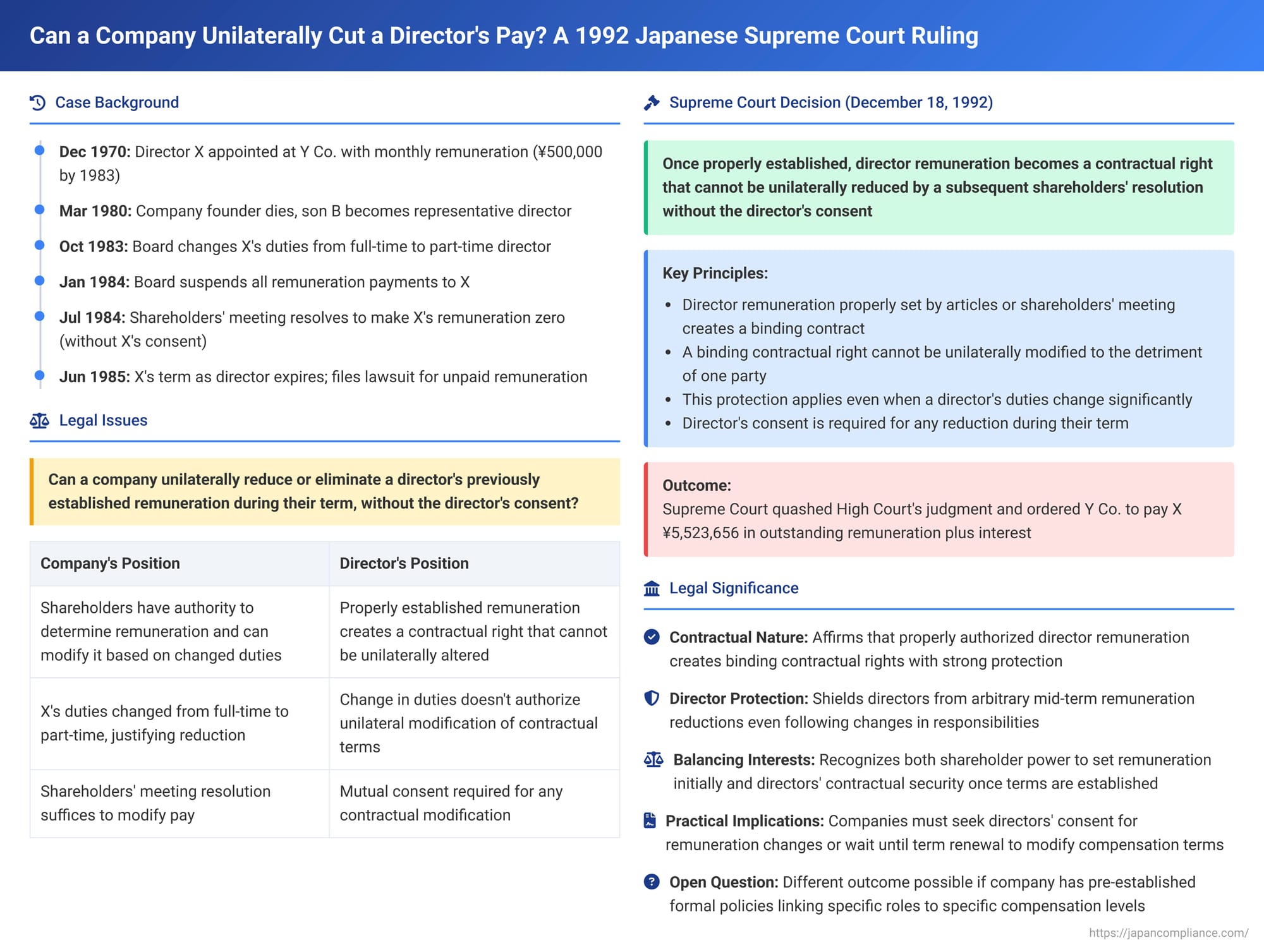

The remuneration of company directors is a critical aspect of corporate governance, typically determined by the company's articles of incorporation or by resolutions of its shareholders' meeting. Once this remuneration is set, a fundamental question arises: can the company, through a subsequent shareholders' vote, unilaterally reduce or even eliminate a director's pay during their term, especially if the director's responsibilities or working conditions change?

This issue was brought before the Second Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan, leading to a significant decision on December 18, 1992, which clarified the contractual nature of duly authorized director remuneration.

The Legal Framework: Setting Director Remuneration in Japan

Under Japanese company law (then the Commercial Code, Article 269, principles now reflected in Article 361, Paragraph 1 of the Companies Act), the remuneration of directors must be specified either:

- In the company's articles of incorporation, or

- By a resolution of the shareholders' meeting.

This requirement ensures that shareholders, as the owners of the company, have ultimate control over the compensation paid to those entrusted with managing the company. Often, shareholders' meetings will approve an aggregate upper limit for the total remuneration to be paid to all directors, with the board of directors then deciding on the specific allocation to each individual director within that approved ceiling.

The Case of Director X and Y Co.

The case involved Mr. X (Kiyomi Suzui in the judgment), a director of Y Co. (Kyouritsu Souko K.K.), and a dispute over his remuneration.

- Initial Remuneration Agreement: Mr. X had been a director of Y Co. since December 1970. The company's articles of incorporation stipulated that director remuneration would be determined by a shareholders' meeting resolution. Accordingly, a shareholders' meeting had set an overall maximum amount for director remuneration. Based on this, Y Co.'s board of directors had subsequently resolved to pay its directors, including X, a fixed monthly sum. As of December 1983, X was receiving 500,000 yen per month.

- Change in Circumstances and Disputes: Following the death of Y Co.'s founder, Mr. A, in March 1980, Mr. A's eldest son, B, assumed the role of representative director. Over time, disagreements and conflicts arose between the new representative director B and Director X.

- Change in Duties and Suspension of Pay: In October 1983, Y Co.'s board of directors passed a resolution changing X's duties from those of a full-time director to those of a part-time director. Subsequently, in January 1984, the board resolved to suspend all remuneration payments to X from that month onwards.

- Shareholders' Resolution to Make Remuneration Zero: In July 1984, Y Co.'s shareholders' meeting passed a resolution to make Director X's remuneration zero. X did not consent to this resolution.

- Retirement and Lawsuit: X continued to serve as a director until his term expired on June 14, 1985. He then filed a lawsuit against Y Co., seeking payment of his unpaid remuneration from January 1984 until his retirement.

The lower courts partially recognized X's claim, leading to Y Co.'s appeal to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Decision (December 18, 1992)

The Supreme Court, in a unanimous decision, ruled decisively in favor of Director X.

Authorized Remuneration Forms a Binding Contract

The Court laid down a fundamental principle: When the amount of a director's remuneration has been specifically determined in accordance with the law—either by a provision in the articles of incorporation or by a resolution of a shareholders' meeting (including scenarios where the shareholders' meeting sets an aggregate amount and the board of directors subsequently allocates specific amounts to individual directors)—that determined remuneration amount becomes a contractual term between the company and the director. This contract is binding on both parties: the company and the individual director.

Unilateral Reduction by Subsequent AGM Resolution Impermissible Without Director's Consent

Building on this contractual foundation, the Supreme Court held that: Because the agreed-upon remuneration is a contractual right, a subsequent resolution by the shareholders' meeting cannot unilaterally reduce or eliminate that director's remuneration for the remainder of their term without the director's explicit consent. Once the terms are set and the contract is in effect, one party (the company, acting through its shareholders) cannot simply change those terms to the detriment of the other party (the director) without mutual agreement.

This Principle Applies Even if Director's Duties Change Significantly

Critically, the Supreme Court clarified that this contractual protection of the agreed-upon remuneration remains robust even if there has been a significant change in the director's duties, and even if the shareholders' resolution to reduce or eliminate the remuneration was made on the premise of these changed duties. In X's case, his change from a full-time to a part-time director did not give the shareholders the right to unilaterally void his existing contractual entitlement to the previously agreed remuneration.

Outcome of the Case

Applying these principles, the Supreme Court found that the July 1984 shareholders' meeting resolution making X's remuneration zero, to which X had not consented, did not strip him of his right to claim the remuneration previously established. The High Court had erred in finding that X lost his right to remuneration from the day after that AGM resolution.

The Supreme Court therefore quashed the part of the High Court's judgment that had been unfavorable to X. It then directly calculated the outstanding amount owed to X (5,523,656 yen for the period from July 14, 1984, to June 14, 1985) and ordered Y Co. to pay this sum along with statutory interest for late payment.

Analysis and Implications

This 1992 Supreme Court decision carries significant weight in defining the nature of director compensation in Japan.

- The Strength of Contractual Rights: The ruling strongly underscores that once director remuneration is properly authorized through statutory procedures, it crystallizes into a binding contractual right for the director. This right cannot be easily overridden by subsequent shareholder decisions without the director's consent.

- Distinguishing Scenarios for Remuneration Changes: Academic commentary (as noted in the provided PDF source ) often categorizes potential changes to director remuneration into three scenarios:

- No change in the director's duties: It was generally accepted even before this Supreme Court ruling that remuneration could not be altered without the director's consent in such cases. This 1992 decision is consistent with that view.

- Change in the director's duties, but no pre-existing, objective criteria linking specific duties or roles to specific remuneration levels: This was the situation in Director X's case. The Supreme Court clearly held that even with a change in duties, the contractually agreed remuneration is protected unless the director consents to a change.

- Change in the director's duties, and the existence of pre-set, objective, and known criteria within the company that link specific roles or levels of responsibility to specific remuneration amounts (e.g., a formal company policy stating that a full-time director receives X amount, while a part-time director receives Y amount): The Supreme Court's 1992 judgment did not directly address this third scenario, as such criteria were not present in X's case. It is suggested by some legal scholars and certain lower court rulings that if such clear, pre-existing, and known criteria are in place, a change in a director's role could legitimately and automatically lead to an adjustment in their remuneration according to those established criteria.

- Protection Afforded to Directors: The decision provides substantial protection to directors against arbitrary reductions in their agreed-upon compensation by shareholders during their term of office, even if their operational responsibilities are modified.

- Company's Options for Adjusting Remuneration: If a company finds itself in a situation where a director's duties have significantly changed and it wishes to adjust their remuneration downwards, this ruling implies that the company would typically need to:

- Seek and obtain the director's explicit consent to a revised remuneration package.

- Alternatively, if consent is not forthcoming, the company might have to consider other avenues, such as a formal dismissal of the director (though this could potentially lead to claims for damages for dismissal without just cause, as provided under Article 339, Paragraph 2 of the Companies Act) and then, if desired, attempt to re-negotiate terms should the individual be re-engaged in a different capacity or role.

Conclusion

The 1992 Supreme Court decision powerfully affirms that once a director's remuneration is specifically and properly established through the company's articles of incorporation or a resolution of its shareholders' meeting, it creates a binding contractual obligation on the company. This contractually agreed remuneration cannot be unilaterally reduced or eliminated by a subsequent shareholder vote during the director's term—even if the director's duties undergo significant changes—unless the director themselves consents to the alteration.

The ruling champions the contractual security of director compensation once it has been duly authorized. While it leaves open for discussion scenarios where remuneration is explicitly and formally tied to specific roles under pre-defined company policies, it sends a clear message about the limitations on shareholder power to alter existing contractual remuneration terms mid-stream without mutual agreement.