Can a Company Limit Your Choice of Proxy to Fellow Shareholders? A Japanese Supreme Court Ruling

Judgment Date: November 1, 1968

Case: Action for Nullity of Shareholders' Meeting Resolution (Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench)

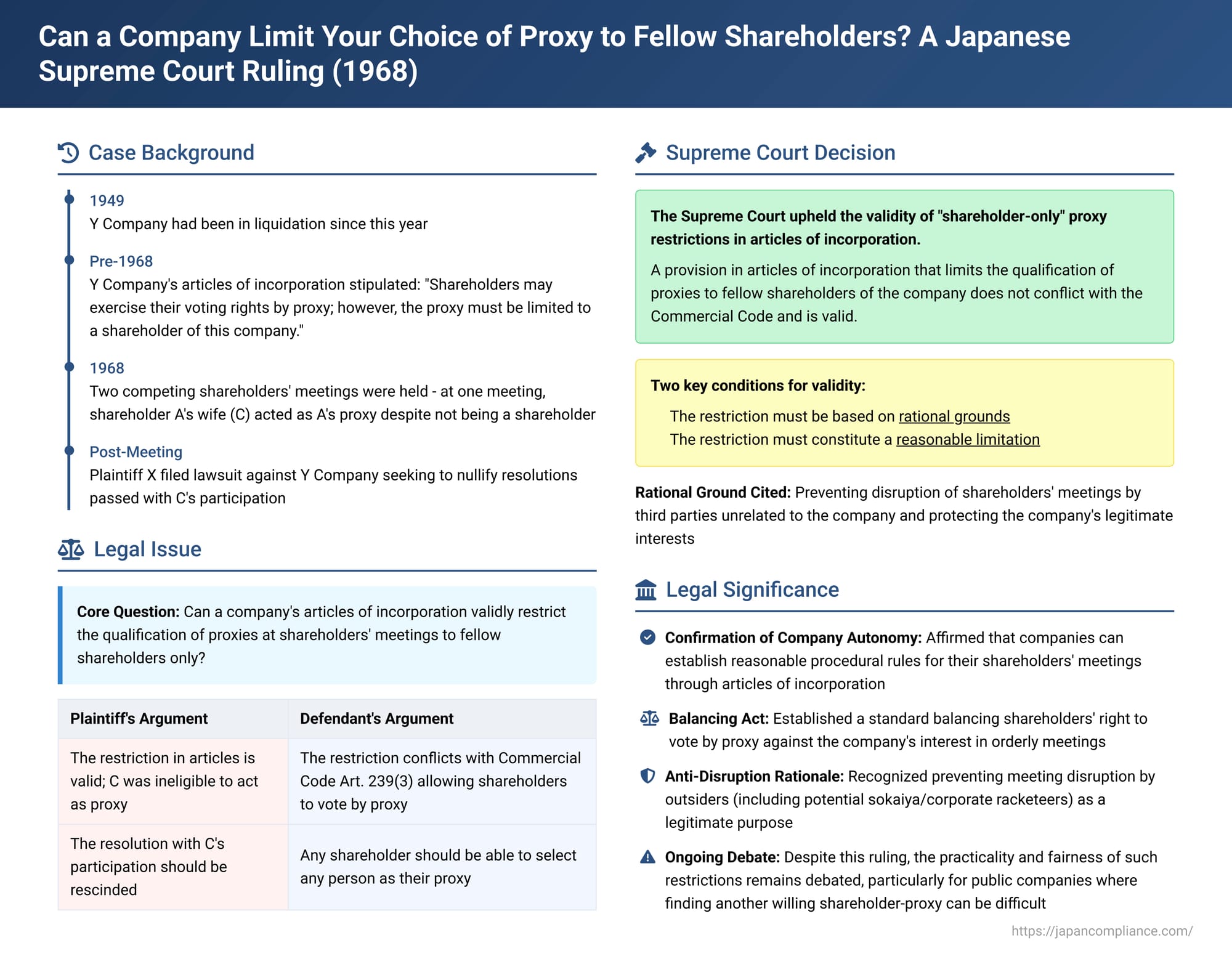

This 1968 Japanese Supreme Court decision tackled a common and often debated provision in company articles of incorporation: Is it permissible for a company to restrict the eligibility of individuals who can act as proxies for shareholders at general meetings to only other shareholders of that same company? The Court found such a restriction to be generally valid, provided it is based on reasonable grounds and constitutes a reasonable limitation.

Factual Background: A Liquidating Company, Dueling Meetings, and a Non-Shareholder Proxy

The dispute arose within Y Company, a family-owned business that had been in liquidation since its dissolution in 1949.

- Shareholder Dissatisfaction and Call for Meeting: A group of shareholders, X et al. (the plaintiffs), were dissatisfied with the performance of A, the incumbent liquidator of Y Company, alleging neglect of duties. They formally requested the convocation of an extraordinary shareholders' meeting to address A's dismissal and the appointment of a successor.

- Contentious Meetings: The shareholders' meeting that was eventually convened based on this request became highly contentious and ultimately fractured into two separate, parallel meetings (referred to as Meeting 甲 and Meeting 乙).

- At Meeting 甲, shareholder X assumed the role of chairman. Resolutions were passed to dismiss liquidator A and to appoint B as the new liquidator.

- At Meeting 乙, a different group of individuals (C, D, E, F, G, H) gathered. They approved the purported resignation of liquidator A and then passed a resolution (the "Resolution in Question") appointing D as the new liquidator. A key detail concerning Meeting 乙 was that A themselves was absent; A's wife, C, attended and exercised A's voting rights by proxy.

- Legal Battles Ensue: B, the liquidator appointed at Meeting 甲, was quickly registered with the authorities. This prevented D, the liquidator purportedly appointed at Meeting 乙, from being registered. Consequently, C, D, and E (from the Meeting 乙 faction) initiated a separate lawsuit against Y Company (then represented by B) seeking to nullify the resolutions passed at Meeting 甲. This separate lawsuit was ultimately unsuccessful; C, D, and E lost their case.

- The Current Lawsuit: Following these events, X (representing the Meeting 甲 faction) filed the present lawsuit against Y Company (which, for the purpose of this suit's initiation, was nominally represented by D, based on the contested Meeting 乙 resolution). X sought, primarily, a declaration that the resolutions of Meeting 乙 were non-existent; secondarily, a declaration of their nullity; and tertiarily, their rescission.

- Lower Court Findings: Both the first instance court and the High Court found that C, D, E, F, G, and H were not actually shareholders of Y Company. More importantly, they noted that Y Company's articles of incorporation contained a specific provision regarding proxy voting: "Shareholders may exercise their voting rights by proxy; however, the proxy must be limited to a shareholder of this company."

Since C (A's wife) was not a shareholder of Y Company, her act of exercising A's voting rights by proxy at Meeting 乙 was deemed a violation of this article of incorporation. On this basis, the lower courts rescinded the Resolution in Question from Meeting 乙 (which had appointed D as liquidator). Y Company (represented by D) then appealed this decision to the Supreme Court, arguing that the article restricting proxy eligibility solely to other shareholders was itself invalid because it conflicted with the then-Commercial Code Article 239(3), which broadly permitted shareholders to vote by proxy.

The Supreme Court's Judgment: "Shareholder-Only" Proxy Restriction Upheld

The Supreme Court dismissed Y Company's appeal, thereby affirming the lower courts' decision to rescind the resolution from Meeting 乙.

The Court's core reasoning was as follows:

- Article 239(3) of the Commercial Code (the predecessor to Article 310(1) of the current Company Law), which grants shareholders the right to vote by proxy, should not be interpreted as prohibiting companies from imposing reasonable restrictions on the qualifications of those proxies through their articles of incorporation, provided there are rational grounds for such limitations and the limitations are of a reasonable extent.

- The specific provision in Y Company's articles of incorporation, limiting proxy eligibility to existing shareholders of the company, was found to serve the purpose of preventing the disruption of shareholders' meetings by third parties who are not otherwise connected to the company, thereby protecting the company's legitimate interests.

- The Court deemed this purpose to be a rational ground and the restriction itself to be a reasonable degree of limitation.

- Therefore, the Supreme Court concluded that such an article of incorporation is valid and does not unlawfully conflict with the statutory provision allowing shareholders to vote by proxy.

Since C was not a shareholder of Y Company, her exercise of proxy votes on behalf of A at Meeting 乙 was a violation of Y Company's valid articles of incorporation. This made the resolution passed at Meeting 乙 (appointing D as liquidator) susceptible to rescission.

Analysis and Implications: Balancing Shareholder Rights and Company Interests

This 1968 Supreme Court decision remains a key precedent in Japanese corporate law regarding a company's ability to regulate proxy voting at its shareholders' meetings.

1. The Shareholder's Right to Vote by Proxy:

The right to vote is a fundamental aspect of share ownership, often termed a "common benefit right" (kyoeki-ken) that allows shareholders to participate in the governance of the company. Because shares are generally considered impersonal financial assets, the exercise of voting rights is naturally suited to being performed by a proxy. This right is also viewed as an "inherent right" (koyu-ken) of shareholders, essential for their participation as owners of the company, and cannot be arbitrarily denied by the company's articles or resolutions, except under specific legal exceptions. Article 310(1) of the current Company Law (and its predecessor, then-Commercial Code Art. 239(3)) statutorily confirms and guarantees the shareholder's ability to vote by proxy. This is particularly vital in public companies where shareholders may be geographically dispersed and unable to attend meetings personally, especially since meeting dates are often determined unilaterally by the board.

2. The Common "Shareholder-Only" Proxy Restriction:

Despite the general right to appoint a proxy, it is a very common practice for Japanese companies, like Y Company in this case, to include a provision in their articles of incorporation restricting the qualification of proxies to individuals who are already shareholders of that company. This directly curtails a shareholder's freedom to choose any person they trust to act as their agent, leading to the central legal question: Is such a restriction valid? If the restriction is valid, then C's vote was improper, and the resolution was rightly rescinded. If the restriction itself is invalid, then C could validly act as a proxy, and that specific defect would not apply to the resolution.

3. The Supreme Court's "Reasonable Restriction" Standard:

The Supreme Court established a general principle that articles of incorporation can impose restrictions on proxy qualifications, but only if these are "reasonable restrictions based on rational grounds". This implies a two-pronged test: the reason for the restriction must be legitimate (rationality of purpose), and the method or extent of the restriction must not effectively nullify the shareholder's ability to exercise their vote by proxy (reasonableness of the method).

4. Rationality of Limiting Proxies to Shareholders:

The Court found the rationale for the "shareholder-only" proxy rule—namely, "preventing disruption of shareholders' meetings by third parties unrelated to the company and thereby protecting the company's interests"—to be reasonable and legitimate. This view is supported by a majority of legal scholars in Japan.

However, this rationale has faced criticism:

- "Company Interests" vs. Minority Rights: In a system governed by majority rule, "company interests" can often align with the "interests of the majority shareholders." Using this to limit voting rights could potentially conflict with the inherent nature of such rights, especially for minority shareholders.

- Relevance in Public Companies: For public companies where shares are freely tradable and anyone can become a shareholder and vote, the argument that non-shareholder proxies inherently threaten "company interests" by causing disruption is less convincing.

- The "Anti-Sokaiya" Argument: A commonly cited underlying reason for these clauses since the Meiji era has been to act as a defense against sokaiya (corporate racketeers who disrupt meetings for payoffs). The idea is that requiring sokaiya to first invest in shares to become eligible proxies creates a barrier. While this may have some defensive effect, it's debatable whether allowing non-shareholder proxies automatically leads to meeting disruption, especially given that comprehensive regulations against sokaiya activities are now in place. Is this historical concern still a sufficient "rational ground" to limit an inherent shareholder right?

5. Reasonableness of the "Shareholder-Only" Method:

The Supreme Court implicitly found this particular method of restriction—limiting proxies to fellow shareholders—to be a "reasonable degree" of limitation. However, this also faces critiques:

- Practical Difficulty for Public Company Shareholders: In large public companies, it can be very difficult for an individual shareholder to find another willing shareholder to act as their proxy, potentially making this restriction unreasonable in practice. Early drafters of Japanese company law had raised this exact concern, arguing for the invalidity of such clauses.

- A Differentiated Approach? Some scholars propose that "shareholder-only" proxy clauses should be considered void for public companies due to this difficulty but valid for non-public companies that intentionally maintain a closed, personal character among their shareholders. However, even in non-public companies, such a rule could isolate a minority shareholder who is in conflict with the majority and cannot find another shareholder willing to act as their proxy, effectively disenfranchising them.

6. Exceptions and Practical Challenges:

Even when "shareholder-only" proxy clauses are deemed generally valid, courts have carved out exceptions through restrictive interpretation of the articles, particularly where:

- There is no genuine risk of meeting disruption.

- The shareholder would otherwise be effectively deprived of their voting right.

Examples include allowing a non-shareholder son or nephew to act as proxy for an ill or hospitalized shareholder, or allowing an employee of a corporate shareholder (or a staff member of a local government shareholder) to act as proxy. Some lower courts have extended this to allow non-shareholder lawyers to act as proxies if no risk of disruption is perceived, though other courts have disagreed, fearing that case-by-case judgments on a proxy's potential for disruption could lead to chaos at meeting receptions and arbitrary decisions.

This case-by-case approach creates significant practical difficulties. If a company incorrectly permits an ineligible proxy or wrongly excludes a potentially eligible one based on its interpretation of the articles and the specific circumstances, the resolutions passed at the meeting could be challenged and potentially rescinded. The risk of misjudgment by company personnel at the meeting venue is high. This inherent difficulty in consistent and fair application is another argument used by those who favor deeming such restrictive articles void.

7. Current Practices and Beneficial Owners:

In modern practice, especially for listed companies, there's an increasing trend of allowing institutional investors, who are the beneficial owners of shares, to attend meetings as proxies for the registered nominee shareholders (e.g., trust banks or custodian securities firms). This is often justified under a "rational interpretation" of the articles, as these beneficial owners are the true economic stakeholders and are unlikely to disrupt meetings. However, if beneficial owners can already direct the voting of their shares through the nominee holder, it's debatable whether a "shareholder-only" proxy rule genuinely deprives them of their voting opportunity. Some commentators argue that current practices regarding beneficial owner proxies in listed companies might be stretching the boundaries of existing case law and suggest that the simplest solution would be for companies to abolish these "shareholder-only" proxy restrictions from their articles altogether.

Conclusion: A Balancing Act Between Company Order and Shareholder Rights

The 1968 Supreme Court decision established that a company's articles of incorporation can validly restrict the qualification of proxies at shareholders' meetings to fellow shareholders, provided such a restriction is based on reasonable grounds (such as preventing meeting disruption and protecting company interests) and represents a reasonable degree of limitation on the shareholder's general right to appoint a proxy. While this ruling provides a legal basis for a common corporate practice in Japan, it continues to be the subject of academic debate and practical challenges, particularly concerning its application across different types of companies (public vs. non-public) and the inherent tension between safeguarding perceived "company interests" and ensuring the effective and practical exercise of voting rights by all shareholders, especially those in a minority position. The evolution of corporate practices, particularly with regard to institutional investors and beneficial ownership, further tests the traditional understanding and application of this rule.