Can a Blind Person Witness a Notarized Will in Japan? A 1980 Supreme Court Ruling

Date of Judgment: December 4, 1980 (Showa 55)

Case: Supreme Court of Japan, First Petty Bench, Case No. Showa 52 (o) No. 558 (Claim for Cancellation of Ownership Transfer Registration, etc.)

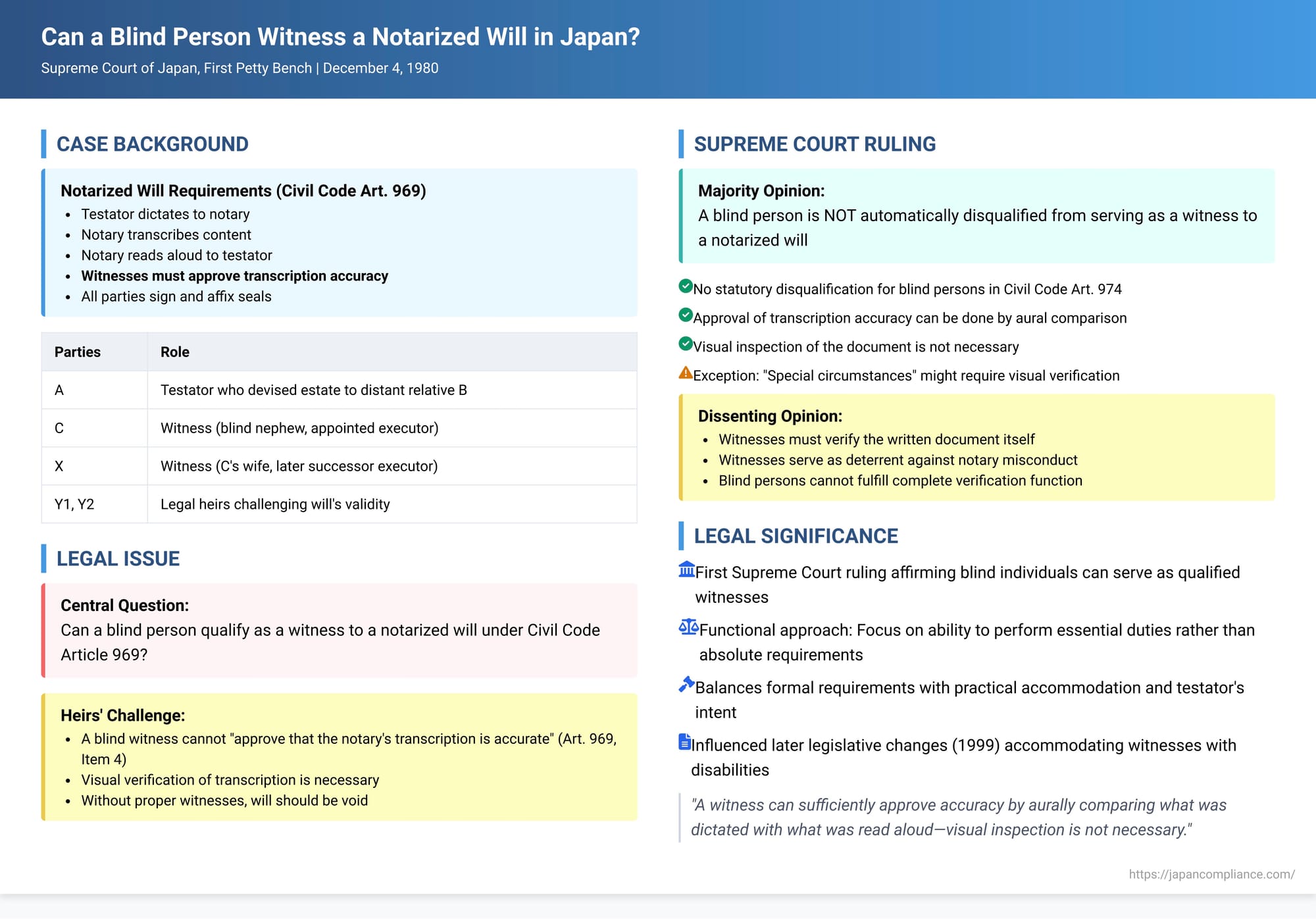

The creation of a legally valid will in Japan is governed by strict formal requirements designed to ensure the testator's true intentions are accurately recorded and to prevent fraud or disputes after their death. For a notarized will (公正証書遺言 - kōsei shōsho igon), one of the most secure forms, Article 969 of the Civil Code mandates the presence of at least two witnesses. These witnesses play a crucial role, including attesting to the accuracy of the notary's transcription of the testator's oral declarations. This raises a significant question: can a person who is blind fulfill these duties and serve as a qualified witness? The Supreme Court of Japan addressed this issue in a pivotal decision on December 4, 1980.

Facts of the Case: A Blind Witness and a Challenged Will

The case revolved around the notarized will of A, who passed away approximately three months after its execution.

- The Testator and the Will's Content: A created a notarized will devising his entire estate to B, a distant relative. The will also appointed C, A's nephew, as the will executor.

- The Witnesses to the Will: Two individuals were present as witnesses during the notarization process: C (the aforementioned will executor) and X (C's wife, who later became the plaintiff/appellee in the Supreme Court after succeeding C as executor).

- The Contested Witness's Condition: C, one of the two witnesses, was blind. His official certificate of physical disability recorded him as totally blind, with vision rated as zero in both eyes (Grade 1 disability). While C was capable of signing his own name by estimation (i.e., from memory of its form, without visually seeing it), he could not visually discern or read written characters.

- The Heirs-at-Law and Their Actions: A's legal heirs-at-law (who would inherit if the will was invalid) were Y1 and Y2 (the defendants/appellants). After A's death, Y1 and Y2 proceeded to register co-ownership of A's real estate in their names, each claiming a 1/2 statutory share. They also made ownership preservation registrations for previously unregistered real estate owned by A, again based on their statutory inheritance rights.

- The Lawsuit to Enforce the Will: C, in his capacity as the appointed will executor, initiated a lawsuit against Y1 and Y2. He sought the cancellation of the property registrations Y1 and Y2 had made based on statutory inheritance, to allow the terms of A's notarized will (which devised the estate to B) to be implemented. After C passed away during the first instance proceedings, his wife X was appointed as the will executor and took over the lawsuit.

- The Heirs' Defense – Invalidity Due to Blind Witness: Y1 and Y2 defended against the lawsuit by arguing that A's notarized will was invalid. Their core contention was that C, due to his blindness, was incapable of properly fulfilling a critical statutory duty required of a witness for a notarized will: specifically, the requirement under Article 969, Item 4 of the Civil Code that witnesses "approve that the notary's transcription is accurate" (筆記の正確なことを承認し - hikki no seikaku na koto o shōnin shi) after the notary reads it aloud. They argued that a blind person could not truly verify the accuracy of a written document, making C a disqualified witness and rendering the will void for failure to comply with essential formalities.

- Lower Court Rulings Upholding the Will: Both the first instance court and the High Court rejected the arguments of Y1 and Y2. These lower courts upheld the validity of A's notarized will, finding that C's blindness did not disqualify him as a witness. Y1 and Y2 appealed this outcome to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Decision: Blindness Not an Automatic Disqualification

The Supreme Court, by a majority opinion, dismissed the appeal by Y1 and Y2, thereby affirming the validity of the notarized will.

The Majority Opinion reasoned as follows:

- No Explicit Statutory Disqualification: The Court first noted that a blind person is not listed among the categories of individuals explicitly disqualified from acting as a witness for a will under Article 974 of the Civil Code (which lists minors, certain relatives of the testator/beneficiaries, notaries, etc.).

- No General De Facto Disqualification: Beyond the explicit statutory disqualifications, the Court found no general basis to conclude that blindness, in itself, automatically renders a person incapable of fulfilling the responsibilities of a witness for a notarized will.

- Purpose of Witness Presence and Their Duties: The Court outlined the purposes for requiring witnesses in the notarized will process:

- To confirm the testator's identity (i.e., that the person making the will is indeed who they claim to be).

- To confirm that the testator is in a normal mental state and is dictating the contents of the will based on their own free and genuine intentions to the notary.

- To have the witnesses listen to the notary read aloud the transcribed will (which the notary has written down based on the testator's oral dictation) and then to have the witnesses confirm the accuracy of this transcription and approve it. This entire process aims to ensure the testator's true wishes are accurately captured and to prevent future disputes and controversies regarding the will's authenticity and content.

- Method of Approving Transcription Accuracy: This was the central point of contention. The majority held that a witness can sufficiently approve the accuracy of the notary's transcription by aurally comparing what the testator orally dictated to the notary with what the notary subsequently reads aloud from the transcribed document. The Court explicitly stated that it is not necessary for the witness to also visually inspect the written document and visually compare it with what they heard the testator dictate or the notary read. As long as the witness has normal hearing, they can perform this comparative function.

- Exception for "Special Circumstances": The majority did acknowledge a hypothetical, and likely rare, exception. If "special circumstances" were present such that a witness could not independently and reliably approve the accuracy of the notary's transcription without visually comparing the written text with the oral dictation or the notary's reading, then a visually impaired witness might indeed be unable to fulfill this specific duty. For example, if there was a credible reason to suspect the notary was misreading the document, visual verification might become indispensable. In such a specific, exceptional case, the will might be invalidated not because blind persons are generally disqualified, but because of a failure in that particular instance to comply with the procedural requirement of accurate approval due to the witness's inability to overcome the "special circumstance" through other means.

- Application to the Present Case: The Court found that in A's will-making process, there was no evidence suggesting the existence of any such "special circumstances" that would have necessitated visual confirmation by witness C. C had listened to A's dictation to the notary and then listened to the notary read back the transcribed will, and he, along with witness X, had approved its accuracy before signing.

Therefore, the majority concluded that C was a qualified witness and the will was valid.

The Dissenting Opinion:

It is noteworthy that there was a strong dissenting opinion from two justices. The dissent argued:

- The accuracy that witnesses must approve is the accuracy of the notary's written transcription itself against the testator's original oral dictation, not merely the accuracy of the notary's oral reading of that transcription.

- If there is any doubt about whether the notary's reading accurately reflects the written document, the witness has a duty to be able to verify the written document directly.

- While acknowledging that a notary deliberately misrepresenting a will's contents (writing one thing, reading another) would be extremely rare, the dissent emphasized a broader purpose for witness involvement: to act as a deterrent against any potential misconduct by the notary through their presence and oversight capabilities.

- Furthermore, the dissent argued that the involvement of witnesses who are fully capable of all forms of verification (including visual) creates an important outward appearance and formal guarantee that the notarized will was correctly executed. This, in turn, helps to ensure public trust and confidence in the reliability of notarized wills as a method of testamentary disposition. For these reasons, the dissenting justices concluded that a blind person generally lacks the full capacity to fulfill these witness duties and should not be considered qualified.

Legal Principles and Significance

This 1980 Supreme Court decision was a landmark for several reasons:

- First Supreme Court Ruling on Blind Witnesses for Notarized Wills: It was the first time Japan's highest court specifically addressed and affirmed that a blind individual can, in general, be a qualified witness for a notarized will.

- Emphasis on Functional Ability to Perform Duties: The majority opinion adopted a functional approach, focusing on whether a blind person (assuming other senses like hearing are intact) can still perform the essential tasks required of a witness. By defining the crucial duty of "approving the accuracy of the transcription" as something achievable through careful aural comparison, the Court made it possible for visually impaired individuals to serve in this capacity.

- Rejection of Automatic De Facto Disqualification for Blindness: The ruling moved away from older, more traditional views prevalent in some legal scholarship which might have considered blindness a "natural" or de facto disqualification, based on the presumption that visual verification of the written document was indispensable.

- Balancing Formal Requirements with Practicality and Testator's Intent: This decision can be seen as part of a broader trend in Japanese jurisprudence concerning wills, where courts tend to interpret strict formal requirements in a manner that, where possible, upholds the testator's genuine intent, provided the core protective purposes of those formalities are not compromised. It avoids an overly rigid or formalistic interpretation that might unnecessarily invalidate a will due to a witness's physical characteristic if that characteristic does not actually impede the fulfillment of their essential duties.

- The "Special Circumstances" Proviso: While affirming the general qualification of blind witnesses, the majority's acknowledgment of potential "special circumstances" where visual confirmation might become indispensable serves as a narrow safeguard. It implies that challenges could still arise if specific facts demonstrate that a witness's blindness, in a uniquely problematic context, genuinely prevented them from ensuring the will's accuracy.

- Continued Debate Reflected in the Dissent: The presence of a well-reasoned dissenting opinion underscores that the issue was not free from debate. The dissent's emphasis on the witness's role in broader oversight of the notary and in contributing to the objective trustworthiness of the notarization process highlights a more stringent view of witness qualifications.

- Subsequent Legislative Developments: As noted in the PDF commentary, after this judgment, the Japanese Civil Code was amended in Heisei 11 (1999) to include Article 969-2. This article introduces specific alternative procedures for creating notarized wills when the testator or witnesses have hearing or speech impairments (e.g., allowing for communication via sign language or written notes, confirmed by an interpreter if necessary). While Article 969-2 doesn't directly address blindness in the same way, it reflects a legislative trend towards making the will-making process more accessible and accommodating for individuals with various disabilities, a spirit that aligns with the inclusive thrust of the majority opinion in the 1980 decision.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 1980 decision was a significant step in clarifying the qualifications of witnesses for notarized wills in Japan. By concluding that a blind person is not automatically disqualified and can fulfill the requisite duties primarily through aural verification, the Court adopted a functional and less restrictive interpretation of the statutory formalities. While acknowledging that rare "special circumstances" might alter this assessment, the ruling generally affirmed that a witness's blindness does not, in itself, invalidate a notarized will, provided they can still ascertain the testator's identity, confirm their free will, and approve the accuracy of the notary's transcription based on what was orally dictated and read aloud. This judgment balanced the need for procedural rigor in will execution with a practical understanding of how witness duties can be effectively performed.