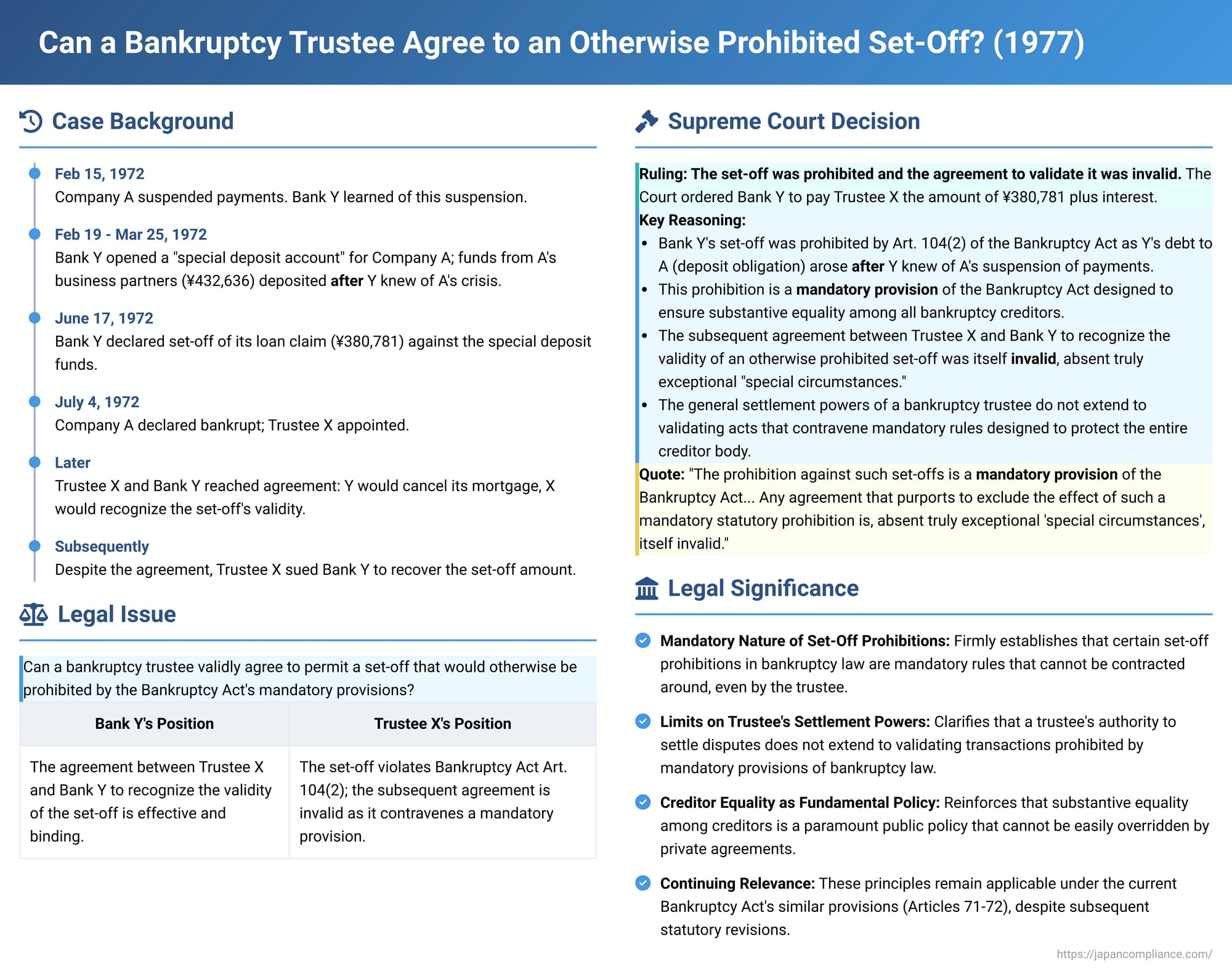

Can a Bankruptcy Trustee Agree to an Otherwise Prohibited Set-Off? A 1977 Japanese Supreme Court Ruling

The right of set-off (相殺 - sōsai) in Japanese bankruptcy law allows a creditor who also owes a debt to the bankrupt estate to net these mutual obligations. This can result in the creditor receiving a de facto preferential payment on their claim. However, to ensure fairness among all creditors, the Bankruptcy Act imposes strict limitations on this right, particularly concerning debts incurred by the creditor to the bankrupt when the creditor already knew of the bankrupt's dire financial situation (e.g., after a "suspension of payments" - 支払停止, shiharai teishi). A key Supreme Court of Japan decision from December 6, 1977, addressed whether a bankruptcy trustee and a creditor could validly agree to permit a set-off that would otherwise be prohibited by these rules. The Court firmly held that such agreements are generally invalid.

Factual Background: Post-Crisis Deposits, Set-Off, and a Subsequent Agreement

The case involved A Co., which faced financial collapse, and its bank, Y Bank.

- On February 15, 1972, A Co. suspended its payments, a clear indication of insolvency. Y Bank became aware of this suspension on the same day.

- Upon learning of the suspension, Y Bank terminated its existing current account agreement with A Co. and, for A Co.'s benefit, opened a new "special deposit account" (別段預金 - betsudan yokin).

- Crucially, between February 19 and March 25, 1972—that is, after Y Bank knew A Co. had suspended payments—funds from A Co.'s business partners were paid into this newly opened special deposit account at Y Bank, intended for A Co. The receipt of these funds by Y Bank created an obligation for Y Bank to repay this deposited amount (totaling 432,636 yen) to A Co. This became Y Bank's debt to A Co. (the "passive claim" for set-off purposes).

- As of June 17, 1972, Y Bank held a pre-existing loan claim (specifically, a claim related to discounted promissory notes - 手形貸付金債権, tegata kashitsukekin saiken) against A Co. amounting to 380,781 yen (Y Bank's "active claim").

- On that same day, June 17, 1972, Y Bank declared its intention to set off its loan claim of 380,781 yen against A Co.'s claim for the 432,636 yen in the special deposit account ("the subject set-off").

Subsequently, on July 4, 1972, A Co. was formally declared bankrupt under Japan's (then) old Bankruptcy Act, and X was appointed as its bankruptcy trustee.

Later, an agreement was reached between trustee X and Y Bank. Under this agreement, Y Bank consented to cancel a basic mortgage (neteitōken) it held as security for its loan claim (the one used in the set-off). In return, trustee X agreed to recognize the validity of "the subject set-off" that Y Bank had effected earlier and promised not to seek repayment of the special deposit funds based on the Bankruptcy Act's rules prohibiting certain set-offs.

Despite this agreement, trustee X subsequently filed a lawsuit against Y Bank, demanding the return of the 380,781 yen that Y Bank had retained through the set-off. X argued that the original set-off was statutorily prohibited and that the subsequent agreement with Y Bank to validate it was also invalid. Both the first instance court and the High Court dismissed trustee X's claim, finding the agreement between X and Y Bank to be effective and thus upholding the set-off. Trustee X appealed this decision to the Supreme Court.

The Legal Issue: Can a Trustee Validate a Prohibited Set-Off by Agreement?

The central legal question for the Supreme Court was whether the provisions of the old Bankruptcy Act prohibiting set-off in certain "crisis period" scenarios—specifically, Article 104, item 2, which restricted set-off when the creditor incurred their debt to the bankrupt after knowing of the bankrupt's suspension of payments—were mandatory rules of public order. If these prohibitions were indeed mandatory, could the parties, even including the bankruptcy trustee representing the interests of the general creditors, validly agree to waive these prohibitions or to legitimize a set-off that was otherwise impermissible under the statute?

The Supreme Court's Ruling: Set-Off Prohibition is Mandatory; Agreement to Validate is Invalid

The Supreme Court, in its judgment of December 6, 1977, partially reversed the lower courts' decisions. It held that the original set-off by Y Bank was indeed prohibited by the Bankruptcy Act, and critically, that the subsequent agreement between trustee X and Y Bank to validate this prohibited set-off was itself invalid, absent special circumstances. Consequently, the Court ordered Y Bank to pay trustee X the sum of 380,781 yen (the amount Y Bank had improperly set off) plus interest.

The Court's reasoning was as follows:

- Prohibition under Old Bankruptcy Act Article 104, Item 2 Applied: The Supreme Court first affirmed that Y Bank's set-off was, in principle, prohibited.

- A Co.'s special deposit account at Y Bank was credited with funds from A Co.'s business partners. Y Bank's obligation to repay this deposit to A Co. arose at the moment Y Bank accepted these incoming funds.

- The record clearly showed that these funds were deposited after Y Bank had become aware of A Co.'s suspension of payments on February 15, 1972.

- Therefore, Y Bank incurred its debt to A Co. (the obligation to return the deposited funds, which served as Y Bank's passive claim for set-off) after it knew of A Co.'s financial crisis.

- Even though Y Bank's active claim (its loan claim against A Co.) had arisen before A Co.'s bankruptcy declaration, the fact that its passive obligation was incurred post-knowledge of the crisis brought the intended set-off squarely within the prohibition of the main provision of old Bankruptcy Act Article 104, item 2. (The Court implicitly found that the exception for passive debts arising from a "cause existing before" knowledge of the crisis did not apply, as the deposits creating this specific debt were new transactions occurring after knowledge).

- Set-Off Prohibition as a Mandatory Rule of Public Policy: The Supreme Court then addressed the validity of the agreement between trustee X and Y Bank. It held that the statutory prohibition against such set-offs (where the creditor's debt to the bankrupt is incurred with knowledge of the debtor's crisis) is a mandatory provision (強行規定 - kyōkō kitei) of the Bankruptcy Act.

- The Court reasoned that the purpose of this prohibition is to ensure substantive equality among all bankruptcy creditors. Allowing a creditor who learns of a debtor's insolvency to then strategically incur a debt to that debtor (e.g., by accepting payments into an account) specifically to create a set-off opportunity would give that creditor an unfair advantage over other creditors and would undermine the collective nature of bankruptcy proceedings.

- Agreements to Circumvent Mandatory Rules are Generally Invalid: Consequently, any agreement between parties—even if one of those parties is the bankruptcy trustee acting for the estate—that purports to exclude the effect of such a mandatory statutory prohibition is, absent truly exceptional "special circumstances" (特段の事情 - tokudan no jijō), itself invalid. The general powers of a bankruptcy trustee to enter into settlements or compromises do not extend to validating acts that contravene fundamental, mandatory rules of bankruptcy law designed to protect the entire creditor body.

- Application to the Present Case: The Supreme Court found no such "special circumstances" in this case that would justify upholding the agreement between trustee X and Y Bank to validate the otherwise prohibited set-off. Therefore, the agreement was void, and the original set-off remained impermissible under the Bankruptcy Act.

The Court also briefly addressed Y Bank's argument that its agreement to cancel the basic mortgage it held on A Co.'s property (as part of the deal with trustee X) constituted a form of "redemption of security" (tanbutsu no ukemodoshi keiyaku) that might justify its retention of the funds. The Court dismissed this, stating that such an argument had not been properly raised or proven in the lower court proceedings and thus could not affect its conclusion.

Significance and Implications of the Judgment

This 1977 Supreme Court decision carries significant weight in Japanese bankruptcy law:

- Reinforces the Mandatory Nature of Certain Set-Off Prohibitions: The judgment firmly establishes that the Bankruptcy Act's rules designed to prevent unfair or opportunistic set-offs—particularly those where a creditor's debt to the bankrupt arises after the creditor becomes aware of the debtor's financial crisis—are not merely default rules that can be easily contracted around. They are mandatory provisions reflecting a core public policy of ensuring creditor equality in bankruptcy.

- Limits a Bankruptcy Trustee's Discretionary Powers in Settlements: It clarifies an important limitation on a bankruptcy trustee's power to enter into agreements or settlements. While trustees have broad authority to manage the estate and resolve disputes, this authority does not extend to validating transactions or arrangements that are fundamentally prohibited by mandatory provisions of the Bankruptcy Act. A trustee cannot, by agreement, legitimize what the law deems an impermissible preference or an act that undermines creditor equality.

- Implicitly Narrows the "Cause Existing Before" Exception for New Deposits: The case strongly suggests that the mere existence of a prior banking relationship or an open bank account does not, in itself, constitute a sufficient "cause existing before" knowledge of the debtor's crisis to permit set-off against new funds deposited into that account after the bank has acquired such knowledge. The critical debt (the bank's obligation to return the deposit) arises when the new deposit is actually made and accepted by the bank, an event occurring post-knowledge. This helps distinguish it from scenarios where a more specific pre-existing contractual right or mechanism directly gives rise to the post-knowledge obligation (as seen in other Supreme Court cases dealing with, for example, pre-crisis note collection mandates).

- Continuing Relevance Under Current Bankruptcy Law: The fundamental principle that statutory set-off prohibitions aimed at ensuring creditor equality are generally mandatory and cannot be easily waived or contracted out of (even by the trustee, absent extraordinary circumstances) remains highly relevant under the current Japanese Bankruptcy Act. The current Act contains similar (though renumbered and slightly rephrased) restrictions on set-off in Articles 71 and 72. The PDF commentary also notes that while the current Bankruptcy Act Article 102 grants a trustee the power to initiate a set-off with court permission if it is in the general interest of creditors, this is typically for specific, limited scenarios (e.g., where the other party is also insolvent and the estate might benefit from netting) and does not give the trustee a general power to agree to a set-off by a creditor that is otherwise prohibited by the Act.

Concluding Thoughts

The Supreme Court's December 6, 1977, ruling serves as a strong affirmation of the mandatory nature of certain set-off prohibitions in Japanese bankruptcy law. It underscores that the goal of ensuring substantive equality among creditors is a paramount public policy that cannot be easily overridden by private agreements, even those involving the bankruptcy trustee. By finding that a trustee cannot validly consent to a set-off that the Bankruptcy Act itself prohibits (specifically, where a creditor incurs their debt to the bankrupt after learning of the bankrupt's suspension of payments, without a qualifying "cause existing before" such knowledge), the Court reinforced the protective framework of bankruptcy law designed to prevent creditors from obtaining unfair, last-minute advantages at the expense of the wider creditor community.