Calculating Damages: Japan's Supreme Court Sets Order for Negligence and Workers' Comp Offset (April 11, 1989)

Japan's Supreme Court (1989) ruled that damages must be reduced for worker negligence before deducting Workers' Accident Compensation benefits.

TL;DR

Japan’s Supreme Court (April 11 1989) held that courts must (1) reduce damages by the worker’s comparative negligence and then (2) deduct Workers’ Accident Compensation Insurance benefits. This “reduce‑then‑deduct” sequence limits tortfeasor liability and prevents double recovery.

Table of Contents

- Factual Background: Accident, Injury, Benefits, and Shared Fault

- The Calculation Dispute: Two Methods in Lower Courts

- Legal Framework: WCAI Act Art. 12‑4 and Coordination

- The Supreme Court’s Analysis (Majority): Reduce First, Then Deduct

- The Dissenting Opinion (Justice Ito)

- Implications and Significance: Standardizing the Calculation Order

- Conclusion

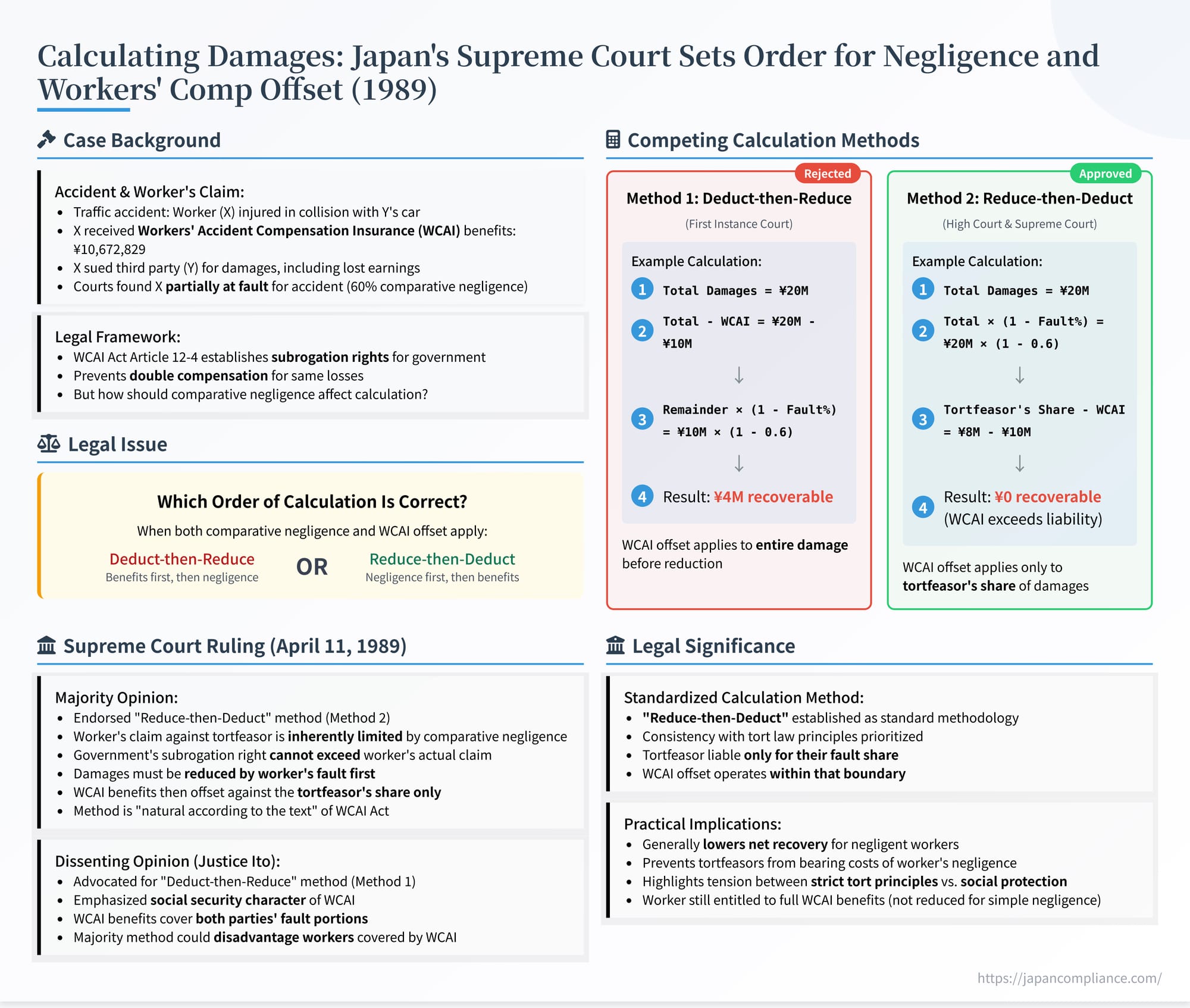

On April 11, 1989, the Third Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan issued a judgment clarifying the correct order of calculation when both comparative negligence (kashitsu sōsai) and the offsetting of Workers' Accident Compensation Insurance (WCAI) benefits apply in tort claims against third parties (Case No. 1988 (O) No. 462, "Damages Claim Case"). When an employee injured in a work-related accident caused by a third party is also partially at fault, their damage award from the third party is reduced. Separately, WCAI benefits received for the same injury may also be deducted to prevent double recovery. The question was: should the WCAI benefits be deducted first, before applying the negligence reduction, or vice-versa? The Supreme Court affirmed the latter approach – first reduce the damages for the worker's negligence, then deduct the WCAI benefits from the remaining amount attributable to the third party's fault. This decision established the standard methodology for such calculations in Japanese tort law involving work-related injuries.

Factual Background: Accident, Injury, Benefits, and Shared Fault

The case arose from a traffic accident involving an employee and a third party:

- The Accident: The appellant, X, was driving a truck when it collided with a car owned by appellee Y1 and driven by appellee Y2. X suffered injuries requiring him to take time off work.

- Work-Related Injury & WCAI Benefits: The injury occurred in the course of X's employment (the specifics of which are not detailed in the judgment text itself, but implied by the WCAI involvement). As a result, X received Temporary Absence Benefits (休業給付 - kyūgyō kyūfu) under the Workers' Accident Compensation Insurance Act (WCAI Act), totaling 10,672,829 yen.

- Tort Claim: X sued the third parties, Y1 (owner) and Y2 (driver), for tort damages, including compensation for lost earnings (休業損害 - kyūgyō songai) resulting from his inability to work.

- Comparative Negligence: The lower courts found that X was also partially at fault for the accident. The first instance court assessed X's comparative negligence at 70%, while the High Court assessed it at 60%.

The Calculation Dispute: Two Methods in Lower Courts

The core legal issue on appeal concerned the proper method for calculating the final damage amount payable by Y1 and Y2, given both X's comparative negligence and his receipt of WCAI benefits intended to cover the same loss (lost earnings). The lower courts used different calculation orders:

- Method 1: Deduct-then-Reduce (Kōjogo Sōsai) - Used by First Instance Court:

- Start with the total assessed loss (e.g., total lost earnings + other damages).

- First, deduct the full amount of WCAI benefits received.

- Second, apply the comparative negligence percentage reduction to the remaining balance.

Example using hypothetical numbers: Total Lost Earnings = 20M yen. WCAI Received = 10M yen. Worker's Fault = 60%.

Step 1: 20M - 10M = 10M. Step 2: 10M * (1 - 0.60) = 4M yen recoverable from tortfeasor.

- Method 2: Reduce-then-Deduct (Kōjomae Sōsai) - Used by High Court:

- Start with the total assessed loss (e.g., total lost earnings).

- First, apply the comparative negligence percentage reduction to determine the portion of the loss attributable to the tortfeasor's fault.

- Second, deduct the WCAI benefits received from this reduced amount.

Example using same numbers: Total Lost Earnings = 20M yen. WCAI Received = 10M yen. Worker's Fault = 60%.

Step 1: 20M * (1 - 0.60) = 8M (Tortfeasor's share of lost earnings). Step 2: 8M - 10M = 0 yen recoverable from tortfeasor for lost earnings (as benefits exceed the tortfeasor's share).

As the examples show, the "Deduct-then-Reduce" method generally results in a higher net recovery for the injured worker from the tortfeasor compared to the "Reduce-then-Deduct" method. X appealed the High Court's use of the latter method.

Legal Framework: WCAI Act Art. 12-4 and Coordination

The resolution depended on interpreting the coordination mechanism established by WCAI Act Article 12-4 (formerly Article 20), which governs situations where a work-related injury is caused by a third party:

- Art. 12-4(1) (Subrogation): If the government pays WCAI benefits, it acquires the worker's damages claim against the third party up to the amount of benefits paid.

- Art. 12-4(2) (Benefit Adjustment): If the worker receives damages from the third party for the "same cause/event," the government is exempted from paying benefits up to that amount.

The Supreme Court had previously established (in cases like the 1977 Sankyo Jidosha decision, analyzed previously) that these provisions reflect a principle of mutual compensability (sōgo hokansei) between WCAI benefits and tort damages covering the same loss, aimed at preventing double compensation (nijū tenpo) for the same damage item. When the government pays benefits, the worker's claim against the third party is reduced because that portion of the claim effectively transfers to the government.

The Supreme Court's Analysis (April 11, 1989 - Majority Opinion): Reduce First, Then Deduct

The Supreme Court, citing its own precedent from Showa 55 (1980), explicitly endorsed the "Reduce-then-Deduct" method used by the High Court and dismissed X's appeal.

1. Rationale Based on the Scope of the Worker's Claim:

The majority's reasoning focused on the legal effect of comparative negligence on the worker's underlying tort claim against the third party:

- When a worker is contributorily negligent, their legally enforceable claim against the third-party tortfeasor is inherently limited. They are only entitled to recover the portion of their damages corresponding to the tortfeasor's share of fault.

- In the Court's words: "...where the worker's negligence should be taken into account in determining the amount of damages, the recipient [worker] merely possesses a damages claim against the third party for the amount determined by taking said negligence into account." (...songai baishōgaku o sadameru ni tsuki rōdōsha no kashitsu o shinshaku subeki baai ni wa, jukyūkensha wa daisansha ni taishi migi kashitsu o shinshaku shite sadamerareta gaku no songai baishō seikyūken o yūsuru ni suginai node...)

2. Impact on Government Subrogation:

Since the government's subrogation right under Art. 12-4(1) is derivative – the government steps into the worker's shoes – the claim the government acquires cannot be larger than the claim the worker actually holds against the third party.

- Therefore, the "damages claim... transferred to the state" under Art. 12-4(1) must also be the claim as already reduced by the worker's comparative negligence.

- The Court found this interpretation to be "natural according to the text" (bunri-jō shizen) of Art. 12-4(1) and consistent with the "purpose of said provision" (migi kitei no shushi ni sō mono).

3. Logical Order of Calculation:

This interpretation dictates the order of calculation:

- First, determine the total damages for the relevant item (e.g., lost earnings).

- Second, apply the comparative negligence reduction to ascertain the actual amount the tortfeasor is liable for (and the maximum scope of the claim the government could potentially subrogate to).

- Third, deduct the WCAI benefits received (for the same damage item) from this negligence-adjusted amount to prevent double recovery for that specific portion of the loss attributable to the tortfeasor.

Conclusion: The High Court's method of reducing for negligence first, then deducting the WCAI benefits, aligns with this legal structure. The Supreme Court found the High Court's judgment correct in principle.

The Dissenting Opinion (Justice Ito)

One Justice dissented, arguing in favor of the "Deduct-then-Reduce" method used by the first instance court.

- Emphasis on Social Security Nature of WCAI: The dissent stressed that WCAI is not pure liability insurance but has a strong social security character, aiming to broadly protect workers even from consequences of their own negligence (unless intentional or grossly negligent, per Art. 12-2-2).

- WCAI Covers Worker's Fault Portion: Therefore, the WCAI benefit paid inherently compensates for both the portion of loss attributable to the third party's fault and the portion attributable to the worker's own fault.

- Limited Subrogation: Consequently, the government's subrogation right should only extend to the portion of the WCAI benefit that corresponds to the loss caused by the third party's negligence. The portion compensating for the worker's own negligence should not be recoverable from the third party.

- Calculation Method: To achieve this outcome, the dissent argued, the calculation should first deduct the entire WCAI benefit from the total damages, and then apply the comparative negligence reduction only to the remaining amount (which represents the uncompensated portion of the third party's liability share).

- Fairness to Worker: The dissent expressed concern that the majority's method could unduly disadvantage workers compared to those not covered by WCAI in some situations and did not fully capture the social protection aspect of the insurance. It acknowledged potential criticisms about increasing the tortfeasor's apparent burden but deemed it justifiable given WCAI's nature.

Implications and Significance: Standardizing the Calculation Order

This 1989 Supreme Court decision settled a significant debate regarding the interaction between comparative negligence and WCAI benefit offsets in third-party liability cases:

- "Reduce-then-Deduct" Method Confirmed: It established the "reduce-then-deduct" approach as the standard methodology in Japan. This means the victim's fault is factored in first to determine the tortfeasor's share of liability, and then social insurance benefits covering the same loss are deducted from that share.

- Impact on Plaintiff Recovery: This method generally results in lower net recovery from the tortfeasor for contributorily negligent workers compared to the alternative method, as the WCAI benefits offset a larger proportion of the already reduced liability amount.

- Focus on Tort Law Allocation: The majority opinion prioritizes a consistent application of tort law principles: the tortfeasor is ultimately liable only for their share of the damages determined after comparative negligence, and the WCAI offset operates within that boundary to prevent double payment for that specific share.

- Dissent Highlights Policy Tension: The dissent highlights an ongoing policy tension: should the coordination rules prioritize strict adherence to tort liability allocation principles, or should they lean towards maximizing the injured worker's overall recovery by leveraging the social security aspects of WCAI (which compensates regardless of worker fault)? The majority favored the former approach in structuring the calculation vis-à-vis the third party.

- Scope of Ruling: It's important to note this ruling dictates the calculation of damages recoverable from the third-party tortfeasor. It does not affect the worker's entitlement to receive the full WCAI benefit from the government (as WCAI benefits themselves are generally not reduced for simple negligence). The adjustment occurs in the tort claim context.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's April 11, 1989, judgment provided a clear rule for calculating damages recoverable from a third-party tortfeasor when the injured worker was contributorily negligent and also received Workers' Accident Compensation Insurance benefits. The Court endorsed the "reduce-then-deduct" method: first, the total damages for the relevant loss (e.g., lost earnings) are reduced by the worker's comparative fault percentage; second, the WCAI benefits received for that same loss are deducted from this negligence-adjusted amount. This approach, grounded in the interpretation of the WCAI Act's subrogation provisions, standardizes the calculation method, though it may result in lower tort recoveries for contributorily negligent workers compared to the alternative calculation order.

- Workers' Comp vs. Consolation Money: Japan's Supreme Court Separates Financial and Non‑Financial Damages (1966)

- What Types of Damages Can Be Claimed and How Are They Calculated in Japanese Torts?

- Japan Supreme Court 2023 Pension‑Cut Ruling: Balancing Sustainability and Recipient Rights

- Workers’ Compensation – Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare