Calculating Appeal Deadlines in Japanese Bankruptcy: Supreme Court Opts for Uniformity Based on Public Notice

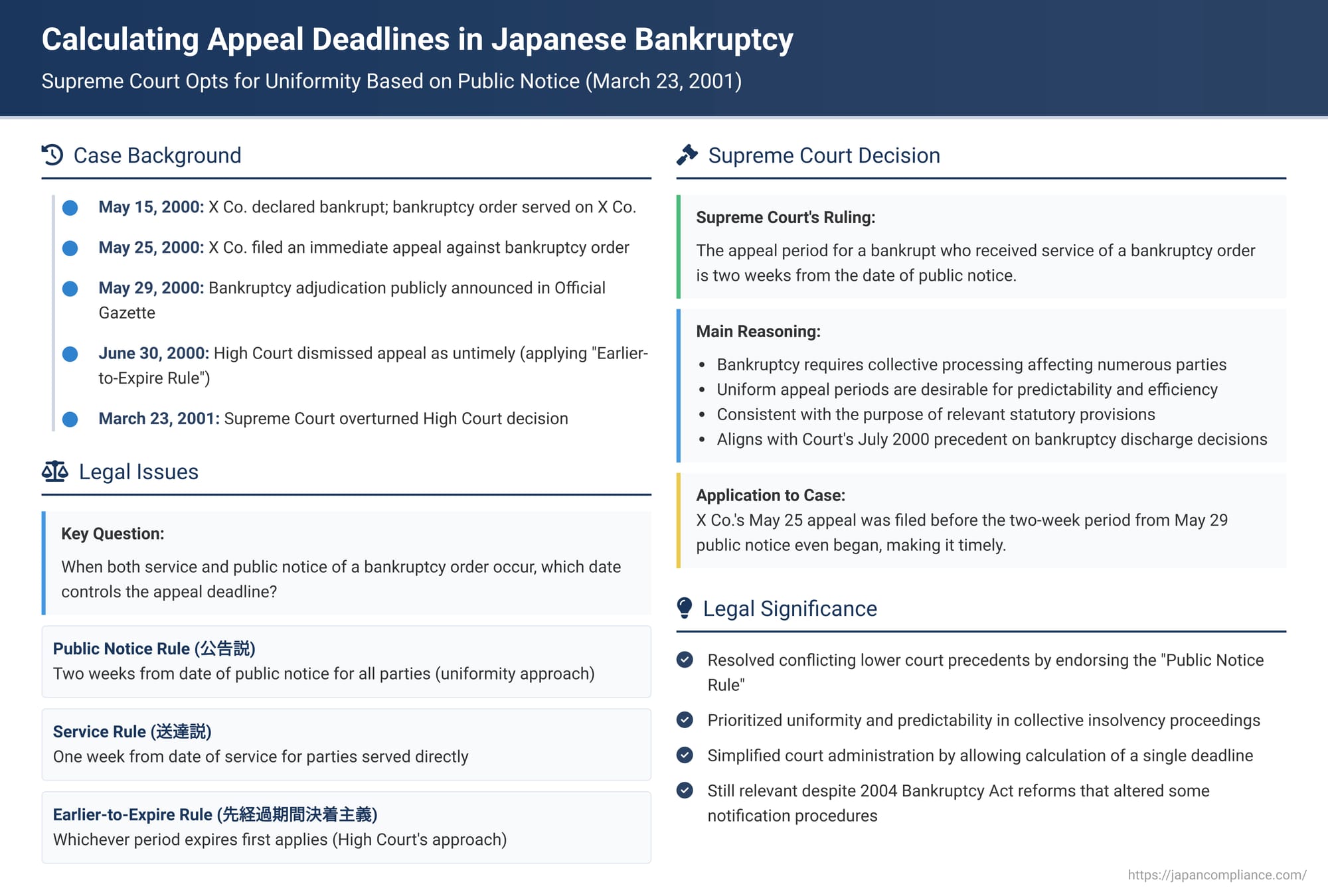

On March 23, 2001, the Second Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan issued a significant ruling on a seemingly technical but crucial procedural point: how to calculate the period for filing an immediate appeal against a bankruptcy adjudication order when the order has been both formally served on the bankrupt party and later publicly announced. The Court favored a rule based on the date of public notice, emphasizing the need for uniformity in collective insolvency proceedings. This decision resolved a split in lower court precedents and provided much-needed clarity.

The Factual Timeline and Lower Court Ruling

The case involved X Co., which was declared bankrupt by the Tokyo District Court on May 15, 2000, following a petition by one of its creditors, A. The formal order of bankruptcy adjudication was served on X Co. on the very same day, May 15, 2000.

Ten days later, on May 25, 2000, X Co. filed an immediate appeal (a fast-track appeal for certain court decisions) against the bankruptcy adjudication. In its appeal, X Co. argued that the debt which formed the basis of the bankruptcy declaration did not actually exist and that the bankruptcy court's examination of the matter had been insufficient. Subsequently, on May 29, 2000, the bankruptcy adjudication order was publicly announced by being published in the Official Gazette.

The Tokyo High Court, acting as the intermediate appellate court, dismissed X Co.'s immediate appeal on June 30, 2000, deeming it untimely. The High Court's reasoning was based on what is sometimes termed the "earlier-to-expire rule." It held that a bankrupt party who has received service of the bankruptcy adjudication order must file an immediate appeal within the period that expires first: either one week from the date of service, or two weeks from the date of public notice. Since X Co. filed its appeal on May 25, 2000—which was more than one week after the May 15, 2000 service date—the High Court concluded that the appeal was out of time and thus procedurally unlawful.

X Co. then sought and obtained permission to appeal this dismissal to the Supreme Court. X Co. argued that, according to the provisions of the (then-applicable) old Bankruptcy Act (specifically Article 112), the immediate appeal period should be two weeks from the date of public notice, and that the High Court had erred in its interpretation of this article and Article 32 of the Constitution (guaranteeing the right to a trial).

The Legal Conundrum: Service Date vs. Public Notice Date for Appeal Deadlines

The core of the dispute lay in the interpretation of the rules governing appeal periods under the old Bankruptcy Act when multiple notification events occurred.

- Generally, for decisions in bankruptcy proceedings, an immediate appeal had to be filed within one week from the day the party received notification of the decision (this was derived from the Code of Civil Procedure via Article 108 of the old Bankruptcy Act).

- However, if a decision was publicly announced (public notice), Article 112, latter part, of the old Bankruptcy Act stipulated an appeal period of two weeks from the date of that public notice.

This created ambiguity when, as in the case of a bankruptcy adjudication order concerning the bankrupt party itself, both service (direct notification to the party) and public notice (general announcement) occurred. Which date should serve as the starting point for the bankrupt's appeal period?

Lower court decisions and legal theories had been divided on this issue:

- The "Public Notice Rule" (公告説 - kōkoku setsu): This approach, also known as the "uniformity rule" (画一説 - kakuitsu setsu), advocated for a consistent appeal period of two weeks calculated from the date of public notice for all parties.

- The "Service Rule" (送達説 - sōtatsu setsu): This held that the one-week period from the date of service should apply to the party who received service.

- The "Earlier-to-Expire Rule" (先経過期間決着主義 - sen keika kikan ketchaku shugi): This rule, also termed the "relativity theory" (相対説 - sōtai setsu), and applied by the High Court in X Co.'s case, stated that the period which concluded earlier (one week from service or two weeks from public notice) would apply.

The Supreme Court's Decision for Uniformity

The Supreme Court overturned the High Court's decision and remanded the case, ruling that X Co.'s appeal was, in fact, timely.

The Court established a clear rule: The immediate appeal period for a bankrupt party who has received service of a bankruptcy adjudication order is two weeks, calculated from the date of public notice of that order.

In reaching this conclusion, the Supreme Court provided the following reasoning:

- This interpretation aligns with the underlying purpose of the relevant statutory provision (Article 112, latter part, of the old Bankruptcy Act, now Article 9, latter part, of the current Bankruptcy Act).

- Crucially, the Court emphasized that in bankruptcy proceedings, which necessitate the collective processing of matters affecting numerous interested parties, it is desirable for appeal periods to be uniformly determined. A single, clear deadline for all involved enhances predictability and administrative efficiency.

- The Court also referenced its own recent decision from July 26, 2000 (Heisei 12 (Kyo) No. 1), which had similarly adopted the public notice date as the standard for calculating the appeal period for bankruptcy discharge decisions, indicating a consistent judicial approach towards uniformity.

- Furthermore, the Court clarified that an immediate appeal filed by a party who had received service before this two-week period (calculated from the date of public notice) even commenced, would still be valid. This was based on Article 108 of the old Bankruptcy Act and relevant articles of the Code of Civil Procedure (specifically, then Article 331 and Article 285, proviso).

Applying this rule to X Co.'s situation: The bankruptcy order was served on X Co. on May 15, 2000. X Co. filed its appeal on May 25, 2000. The public notice of the order was made on May 29, 2000. According to the Supreme Court's ruling, the two-week appeal period began to run from May 29. Since X Co.'s appeal was filed on May 25—even before this period officially commenced—it was well within the permissible timeframe and therefore timely and lawful. The High Court's contrary finding was thus deemed a violation of law clearly affecting the judgment.

Rationale Behind the "Public Notice Rule" and Its Implications

The Supreme Court's adoption of the "public notice rule" (or "uniformity rule") aligned with the majority view in legal scholarship. The main arguments supporting this rule include:

- Textual Interpretation: Consistency with the wording of the old Bankruptcy Act's provisions.

- Uniformity and Predictability: Establishes a single, clear appeal deadline applicable to all interested parties, simplifying matters in complex, multi-party bankruptcy proceedings.

- Protection of Appellants: Public notice often occurs later than individual service, potentially providing a longer effective period for appellants to prepare their appeals.

- Evidentiary Certainty: The date of public notice in the Official Gazette is easily ascertainable, whereas proving the exact date of service (especially if made by ordinary mail under the old system) could sometimes be problematic.

This contrasts with the "earlier-to-expire rule," which prioritized speedy resolution once a specific party was formally made aware of the decision through service. The Supreme Court's decision effectively settled the divergent case law in favor of the public notice standard, thereby promoting legal certainty. A significant practical benefit of this rule is the simplification of court administration, as the court can calculate one deadline based on the public notice date rather than tracking individual service dates for potentially numerous parties.

Relevance Under the Current (Post-2004) Bankruptcy Act

It is important to note that the Japanese Bankruptcy Act underwent a major revision in 2004, after this Supreme Court decision. The new Act significantly reformed and clarified notification procedures. For instance, for bankruptcy adjudication decisions, the requirement for formal service on the bankrupt party was altered; generally, "notice" (which can be less formal than service) to the bankrupt and the bankruptcy trustee is now deemed sufficient (Article 32(3) of the current Act). While service might still be made at the court's discretion, the scenarios where both formal service and public notice create conflicting starting points for the bankrupt's appeal period for the adjudication order itself have been substantially reduced.

Despite these changes, the underlying principle endorsed by the Supreme Court—the desirability of uniform appeal periods in collective proceedings for reasons of efficiency and clarity—remains a significant consideration in insolvency law. Moreover, the ongoing trend towards the digitalization and IT-ization of insolvency proceedings is expected to further strengthen the rationale for centralized and uniform processing methods.

Concluding Thoughts

The Supreme Court's March 23, 2001, decision was a key step in standardizing an important procedural aspect of Japanese bankruptcy law under the old Act. By prioritizing the date of public notice for determining the appeal period against a bankruptcy adjudication, the Court emphasized legal certainty, administrative efficiency, and uniformity in collective insolvency proceedings. While statutory changes have since altered some of the specific notification mechanics, the decision reflects a broader judicial preference for clear and consistent rules in the complex world of bankruptcy.