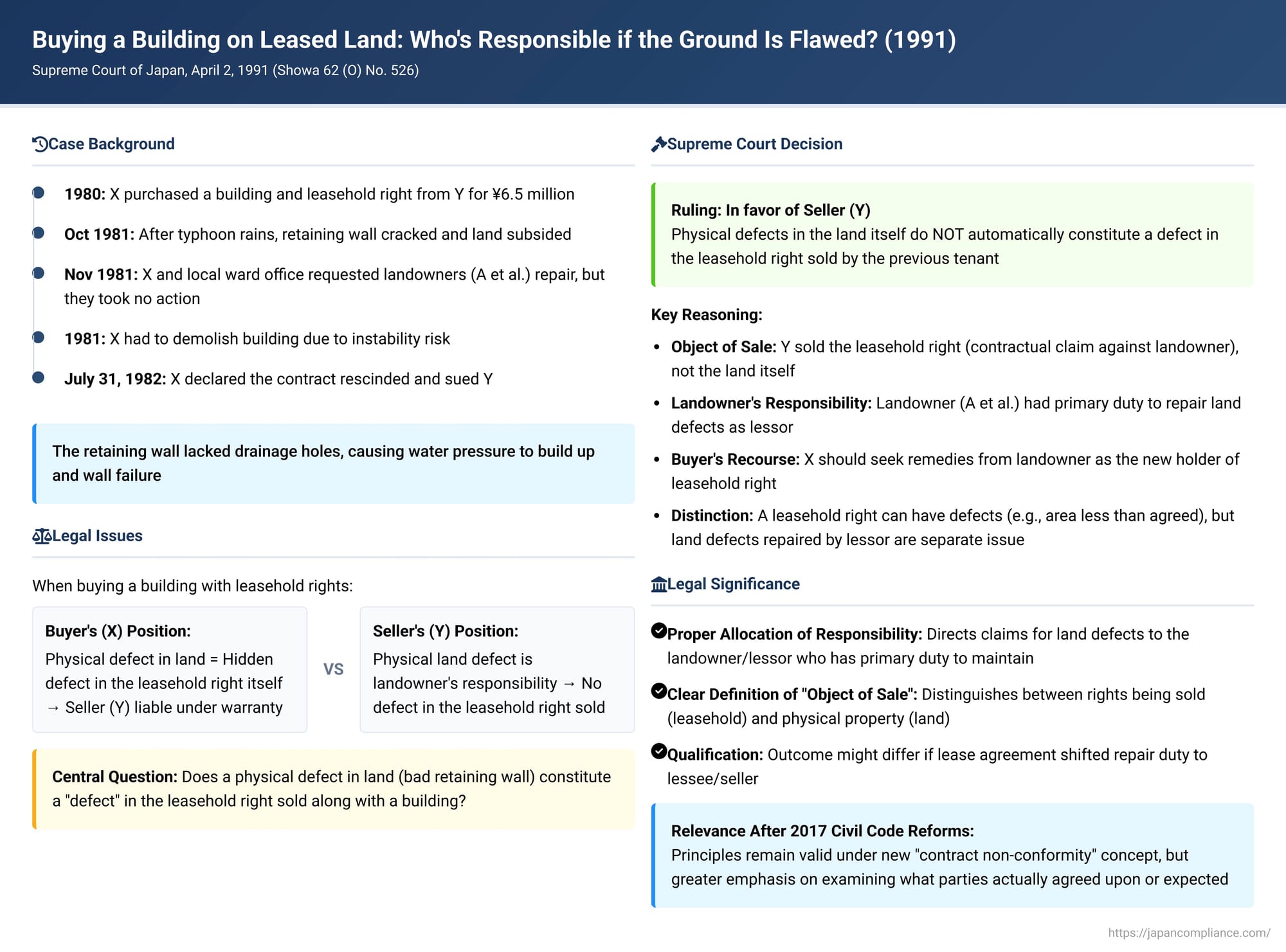

Buying a Building on Leased Land: Who's Responsible if the Ground Beneath It Is Flawed?

When you purchase a building, you naturally expect the ground it stands on to be stable and fit for purpose. But what happens if the building is on leased land, and a serious physical defect with the land itself—like a faulty retaining wall threatening collapse—emerges after you've bought the building and taken over the land lease? Can you hold the person who sold you the building and the leasehold right liable for this underlying land defect under sales warranty principles? Or is your primary recourse against the actual landowner (who is now your lessor) responsible for the land's upkeep? The Supreme Court of Japan addressed this complex issue in a judgment on April 2, 1991 (Showa 62 (O) No. 526).

Selling a Building with a Land Leasehold: Understanding What's Being Transferred

In many property transactions, particularly in urban areas, it's common for a building to be sold while the land it occupies is leased from a separate owner. In such a deal, the buyer typically acquires two distinct things from the seller (who was the previous building owner and land lessee):

- Ownership of the physical building.

- The contractual right to use the underlying land, i.e., the leasehold right (shakuchiken). This leasehold right is essentially a claim against the landowner (lessor) to allow the use of the land under the terms of the lease.

This distinction became central to the Supreme Court's decision.

Facts of the 1991 Case: A Collapsing Retaining Wall and a Demolished Building

The case before the Court involved the following circumstances:

- The Parties:

- X: The buyer of a building and its associated land leasehold right (plaintiff/appellee in the Supreme Court).

- Y: The seller of the building and the land leasehold right. Y was the owner of the building and the lessee of the land from landowners A et al. (defendant/appellant in the Supreme Court).

- A et al.: The actual owners of the land (the lessors).

- The Purchase (1980): X purchased the ownership of a building from Y, along with Y's leasehold right for the land on which the building stood, for a total price of 6.5 million yen.

- The Defect Emerges (1981): More than a year later, in October 1981, after heavy rains from a typhoon, a retaining wall surrounding the leased land tilted and cracked. This caused a portion of the land to subside, and the building X had purchased became dangerously unstable, at risk of collapse.

- The Cause: The hazardous state was attributed to a structural defect in the retaining wall: it lacked necessary drainage holes. This allowed rainwater to accumulate in the soil behind the wall, and the resulting pressure eventually caused the Ōya stone retaining wall to fail.

- Attempts to Rectify and Demolition: In November 1981, both the local ward office (Kita Ward, Tokyo) and X (the buyer) requested the landowners (A et al.) to take necessary safety measures to repair the retaining wall. However, A et al. failed to take any action. Faced with the imminent danger of the building collapsing, X had no choice but to demolish the building.

- X Sues the Seller (Y): X had not been informed by Y of any structural defects in the retaining wall at the time of purchasing the building and leasehold right, and X argued that such a severe problem could not have been foreseen by an ordinary person. X claimed that this situation constituted a "hidden defect" (kakureta kashi) in the leasehold right itself that Y had sold. On July 31, 1982, X declared the sales contract with Y rescinded and sued Y for the return of the purchase price and other damages, based on the seller's warranty provisions in (former) Civil Code Articles 570 and 566, Paragraph 1.

The lower appellate court had ruled in favor of X. It held that if, due to circumstances unknown to the buyer at the time of purchasing a building with an associated land lease, it subsequently became physically difficult to maintain the building on that land, then the leasehold right itself could be considered to have a hidden defect (i.e., it lacked a quality—the ability to support the building safely—that was naturally expected under the contract). Y, the seller, appealed this decision.

The Supreme Court's Ruling: Land Defect is Primarily the Landowner's Responsibility, Not a "Defect" in the Sale of the Leasehold Right by the Previous Tenant

The Supreme Court overturned the appellate court's decision, ultimately ruling in favor of Y (the seller of the building and leasehold right) and dismissing X's claim against Y that was based on a defect in the sale.

Core Finding: The Court established a critical distinction: when a building and the leasehold right to its underlying land are sold by the building owner/land lessee (like Y) to a new buyer (like X), even if a physical defect exists in the land at the time of this sale—a defect for which the actual landowner/lessor (A et al.) would be obligated to make repairs—this situation does not automatically constitute a "hidden defect" in the subject matter of the sale (i.e., the building and the leasehold right) for which the seller (Y) would be liable under sales warranty principles.

Reasoning of the Supreme Court:

- The Object of Sale – Leasehold Right, Not Land Itself: The Court emphasized that when Y sold the package to X, the component related to the land was the leasehold right (a contractual right to use the land), not the ownership of the physical land itself. The land remained the property of A et al.

- Distinguishing Defects in the Leasehold Right from Defects in the Land:

- The Court acknowledged that a leasehold right itself could indeed have a defect that would trigger the seller's warranty. This might occur, for example, if the actual usable area of the leased land was less than agreed, or if there were legal regulations or restrictive clauses within the lease agreement itself that significantly hampered the buyer's intended use of the land for the building. In such cases, where the right to use is objectively impaired by factors intrinsic to the right or its contractual terms, a defect in the sold leasehold right might be found.

- However, a physical defect in the land itself (like the faulty retaining wall), particularly one that the landowner/lessor has a duty to repair under the terms of the lease or general landlord-tenant law (as per former Civil Code Article 606, which generally obligated lessors to make repairs necessary for the lessee's use and enjoyment), should be addressed by the new lessee (X) by demanding such repairs from the landowner/lessor (A et al.).

- Such a physical land defect, which the landowner is primarily responsible for rectifying, cannot be automatically classified as a defect in the leasehold right sold by the previous lessee (Y). The leasehold right, as a claim against the lessor for use, conceptually remains intact; the problem lies with the physical condition of the land that the lessor is supposed to maintain.

- Buyer's Proper Course of Action: The buyer (X), having stepped into Y's shoes as the lessee, should direct their claims for the land defect to the party responsible for the land's condition—the landowners/lessors (A et al.). X could demand that A et al. repair the retaining wall or pursue other remedies available to a lessee against a lessor for defects in the leased property. Holding Y (the seller of the leasehold right) liable under sales warranty for A et al.'s failure to maintain the land was deemed inappropriate.

- Analogy to the Sale of Monetary Claims: The Court drew a parallel with (former) Civil Code Article 569, which dealt with the sale of monetary claims (like a loan). That article generally provided that the seller of a claim did not automatically guarantee the debtor's solvency or ability to pay, unless specifically agreed. Similarly, the Court reasoned, the seller of a leasehold right (Y) does not inherently guarantee the physical perfection of the land underlying that lease, especially concerning defects that the landowner (A et al.) has a primary obligation to repair.

Conclusion in the Case: Although the land had a clear defect due to the faulty retaining wall, and this defect was something the landowners/lessors (A et al.) were responsible for addressing, this did not mean that the leasehold right sold by Y to X was "defective" in a way that would trigger Y's liability under the sales warranty provisions of (former) Article 570.

Significance and Implications

This 1991 Supreme Court judgment provided important guidance on the allocation of responsibility when defects in leased land affect a building sold along with the leasehold.

- Focus on the Precise "Object of Sale": The decision highlights the necessity of carefully distinguishing between the rights being sold (e.g., a leasehold, which is a contractual right against the landowner) and the physical object to which those rights pertain (the land itself, owned by a third party).

- Directing Claims to the Primarily Responsible Party: It generally directs the buyer of a building and leasehold to seek remedies for physical defects in the land from the landowner/lessor, who has the primary duty to maintain the property in a usable condition for the lessee.

- Important Nuance – The Lessor's Duty to Repair: The commentary accompanying the case suggests a critical underlying assumption: the Supreme Court's reasoning hinges on the landowner/lessor actually being obligated to repair the land defect. If the original lease agreement between the landowner (A et al.) and the initial lessee/seller (Y) had, for example, validly shifted the responsibility for such structural land repairs onto the lessee (Y), then Y's subsequent sale of that leasehold right to X (without disclosing the defect or the lessee's repair burden) could arguably constitute the sale of a "defective" leasehold right. In that scenario, Y might be liable to X. Thus, the judgment's scope is likely confined to situations where the landowner retains the primary repair obligation for the land defect.

Relevance After the 2017 Civil Code Reforms ("Contract Non-Conformity")

The principles of this 1991 judgment remain broadly relevant even under Japan's reformed Civil Code (effective April 2020), which replaced the old "hidden defect" warranty system with a more unified concept of "contract non-conformity" (keiyaku futekigō).

- Under the new rules (Article 562 et seq.), if a seller delivers an object (which can include rights like a leasehold) that does not conform to the terms of the contract in type, quality, or quantity, the buyer has various remedies, including demanding cure (repair, replacement, etc.), price reduction, damages, or rescission.

- The 1991 judgment's analytical method—carefully identifying the precise "object of the sale" (the leasehold right as distinct from the land itself) and determining where the primary obligation for rectifying a physical land defect lies (generally with the landowner/lessor)—would still be a crucial starting point for any analysis under the new "contract non-conformity" framework.

- However, the new Code's overarching emphasis on whether the delivered subject matter "conforms to the contract" invites a comprehensive examination of what the parties actually agreed upon or reasonably expected. If the sale of a "building with its land leasehold" was understood by both X and Y to implicitly include an assurance that the land was fundamentally safe and suitable for supporting the building, a severe land defect making it unusable could potentially be argued as a non-conformity in the overall "package" sold by Y. This might give X a more direct claim against Y under the new framework, depending on the specific terms and context of their agreement and what Y could be said to have contractually promised regarding the suitability of the land for the building. The new system encourages a more detailed contractual interpretation to determine the scope of the seller's obligations.

Conclusion

The 1991 Supreme Court decision provides an important clarification regarding a seller's liability when a building is sold along with the leasehold rights to the land it occupies, and a physical defect in that land subsequently causes problems. It establishes that if the landowner (lessor) is primarily responsible for repairing such land defects, the seller of the building and leasehold right is generally not liable to the buyer under sales warranty principles for those land defects; the buyer's recourse is against the landowner. This ruling underscores the importance of distinguishing between the rights being transferred in a sale and the underlying physical property, and it directs claims for land defects toward the party ultimately responsible for the land's condition. However, the specific terms of the lease and sales contracts, particularly concerning repair obligations and any warranties of suitability, remain crucial, especially under the current Civil Code's "contract non-conformity" framework.