Business Income vs. Employment Income: A Japanese Supreme Court's Guiding Principles for Professionals

Case: Supreme Court, Second Petty Bench, Judgment of April 24, 1981 (Showa 52 (Gyo-Tsu) No. 12: Action for Rescission of Income Tax Reassessment Disposition)

Introduction

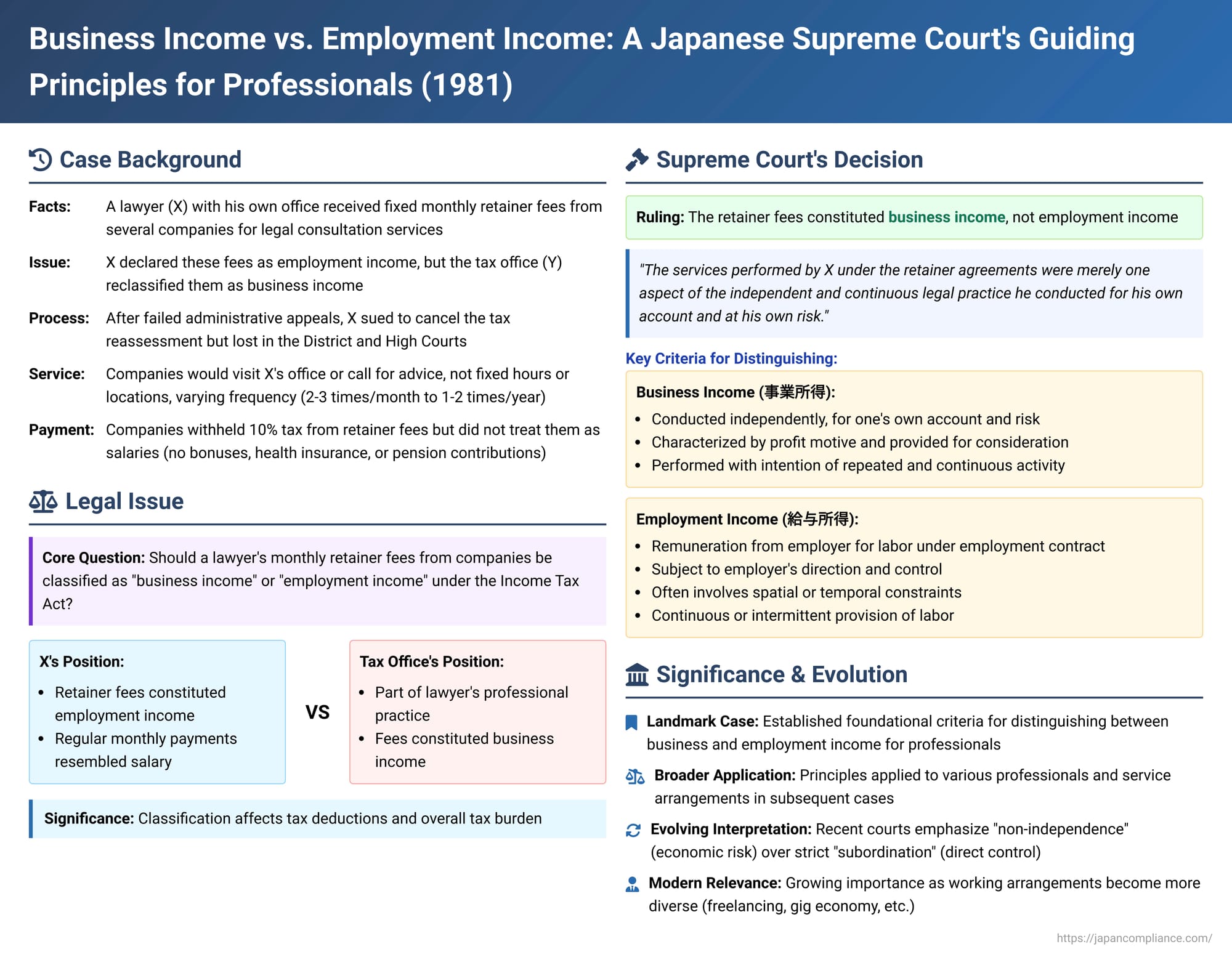

On April 24, 1981, the Second Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan delivered a seminal judgment clarifying the distinction between "business income" (事業所得, jigyō shotoku) and "employment income" (給与所得, kyūyo shotoku) under the Income Tax Act. This case involved a practicing lawyer, X, who received retainer fees from several companies and declared them as employment income. The tax authority, Y, reclassified this income as business income, leading to a dispute that reached the nation's highest court. The Supreme Court's decision laid down foundational criteria for distinguishing these two crucial income categories, emphasizing factors such as independence, risk, control, and the nature of the services provided. This ruling remains a vital reference point, though subsequent judicial interpretations have continued to evolve in response to changing work patterns.

The core issue was whether fixed monthly retainer fees paid by several companies to a lawyer, who operated his own law office, for ongoing legal consultation services should be categorized as business income, derived from his independent professional practice, or as employment income, akin to a salary. The classification has significant implications for tax calculation, including applicable deductions and the overall tax burden.

Facts of the Case

X, the appellant, was a lawyer who maintained his own law office and employed staff. In addition to handling specific legal cases, he provided ongoing legal consultation services. X had entered into oral retainer agreements with several companies to offer such legal advice. Under these arrangements, representatives from these companies would typically visit X's law office as needed to seek his opinion on various legal matters. Each company paid X a fixed monthly retainer fee for these services. These companies withheld 10% income tax from the payments but did not treat the fees as salaries arising from employment contracts.

Despite the companies' treatment, X declared these retainer fees as employment income on his income tax returns for the contested years. The director of the competent tax office, Y (the appellee), challenged this classification and issued a reassessment, categorizing the income as business income. Subsequently, a partial re-reassessment was made, classifying a portion of the income as employment income; however, X remained dissatisfied with the overall outcome. After exhausting administrative appeal procedures, X filed a lawsuit seeking the cancellation of both the initial and subsequent reassessment dispositions.

The Yokohama District Court, as the court of first instance, and the Tokyo High Court, on appeal, both dismissed X's claims, upholding the tax authority's primary classification. This led X to lodge a final appeal with the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Decision

The Supreme Court dismissed X's appeal with respect to the income classification issue, thereby affirming the lower courts' decisions that the retainer fees constituted business income. In its judgment, the Court articulated general principles for distinguishing between business income and employment income.

General Criteria for Distinguishing Business Income and Employment Income

The Supreme Court provided the following framework:

- In determining whether income generated from the performance of services or the provision of labor falls under business income (as defined in Article 27, Paragraph 1 of the Income Tax Act and Article 63, Item 12 of the Income Tax Act Enforcement Order) or employment income (Article 28, Paragraph 1 of the Income Tax Act), it is necessary to consider the specific nature of the services and the income itself. This examination must be conducted in light of the purpose and objectives of the Income Tax Act, which classifies income into various categories (such as business income, employment income, etc.) and prescribes taxation methods appropriate to each category to ensure fair distribution of the tax burden.

- Consequently, retainer fees received by lawyers should not be classified abstractly or generally as either business income or employment income. Instead, the legal character of such fees must be determined based on the concrete details of the advisory services rendered.

- As a preliminary standard for judgment, the Court found it appropriate to distinguish the two income types as follows:

- Business Income (事業所得, jigyō shotoku): This refers to income generated from activities that are (a) conducted independently, for one's own account and at one's own risk; (b) characterized by a profit motive and provided for consideration (onerous nature); and (c) performed with an objectively recognizable intention and social standing of carrying out the activities repeatedly and continuously.

- Employment Income (給与所得, kyūyo shotoku): This refers to remuneration received from an employer as consideration for labor provided under an employment contract or a similar arrangement, where the individual is subject to the employer's direction and control.

- For employment income, particular emphasis should be placed on whether there is some form of spatial or temporal constraint in relation to the payer of the remuneration, whether there is a continuous or intermittent provision of labor or services, and whether the payment is received as consideration for such provision.

Application of the Criteria to X's Case

Applying these general criteria to the specific facts of X's situation, the Supreme Court concluded:

- The facts, as lawfully established by the High Court, indicated that X was a lawyer belonging to the D Bar Association (name anonymized for this context, original was First Tokyo Bar Association). During the years in question (Showa 42-44, i.e., 1967-1969), X operated his own law office, employed several staff members (including family members), and continuously engaged in legal practice, which encompassed not only specific case handling but also legal consultation and expert opinion services.

- The retainer agreements with the various companies were oral. Under these agreements, X was obliged to provide legal advice and opinions as a lawyer, which was not distinct from his ordinary professional duties.

- These agreements did not specify fixed working hours or locations at the client companies. X maintained retainer relationships with several companies concurrently and was not exclusively dedicated to any single company's work, nor was he subject to particular constraints like fixed-time exclusive service.

- The typical mode of service delivery involved clients contacting X by phone or visiting his office for ad-hoc legal advice. X usually provided this advice from his office, often by phone, or in person to representatives visiting his office. He very rarely, if ever, visited the client companies' premises for these consultations. The frequency of consultations varied by company, ranging from two or three times a month to once or twice a year.

- The client companies all treated the retainer fees as remuneration for professional legal services, paying a fixed amount monthly after withholding 10% income tax. They did not deduct health insurance or pension contributions from these fees, nor did they pay X any bonuses (summer, year-end, etc.), indicating they did not consider these payments as salary based on an employment contract.

- Given these circumstances, the Supreme Court held that the services performed by X under the retainer agreements were merely one aspect of the independent and continuous legal practice he conducted for his own account and at his own risk.

- Applying the previously outlined criteria, the income derived from these retainer fees was appropriately classified as business income, not employment income, under the Income Tax Act. The High Court's judgment to this effect was, therefore, correct, and the Supreme Court found no error in it.

Commentary Insights

This 1981 Supreme Court decision is a landmark ruling in Japanese tax law, and its principles have been extensively discussed and applied in subsequent cases.

Significance of Income Classification in Japan

The Japanese Income Tax Act categorizes income into ten distinct types based on its source or nature (e.g., interest income, dividend income, real estate income, business income, employment income, capital gains, etc.). This detailed classification system is rooted in the idea that different types of income possess different qualitative taxable capacities. To ensure fair tax burden distribution, the law prescribes specific methods for calculating the amount of each type of income and applies different taxation methods accordingly. Consequently, the correct classification of a particular stream of income is a matter of critical importance to taxpayers, as it directly affects their tax obligations.

Significance of the 1981 Supreme Court Ruling

This judgment is significant because it represents the Supreme Court's articulation of the criteria for distinguishing between business income (Article 27, Paragraph 1 of the Income Tax Act) and employment income (Article 28, Paragraph 1). Notably, a similar judgment was rendered in a related case involving the same appellant, X, on the exact same day. The criteria set forth in this decision have also been referenced in other contexts, such as a case concerning the income classification of remuneration received by a violinist from an orchestra (Supreme Court judgment, August 29, 1978).

The principles from this 1981 ruling have been consistently applied in subsequent lower court cases involving various professions and service arrangements, including cases concerning commission fees paid to electricity meter readers and income received by members of a civil law partnership for work performed for the partnership's business (Supreme Court judgment, July 13, 2001). Generally, when determining if an activity gives rise to business income, various factors are considered, such as the scale and nature of the activities, the range of clients or customers, and other relevant circumstances, with the final determination often guided by prevailing societal norms and understandings.

Traditional Criteria for Distinguishing Business and Employment Income

As this case illustrates, the distinction between business income (particularly that derived from personal services) and employment income can often be challenging. Historically, the core distinguishing factors have revolved around the concepts of "subordination" (従属性, jūzokusei) and "non-independence" (非独立性, hi-dokuritsusei).

- Business income has been characterized by attributes such as being operated independently for one's own account and at one's own risk, having a profit motive, providing services for consideration, and being conducted with an intention and social standing of repeated and continuous activity.

- Employment income, on the other hand, has been defined as remuneration received as consideration for labor provided subject to an employer's direction and control, based on an employment contract or a similar relationship.

Evolution in Judicial Interpretation: Recent Court Trends

While the 1981 Supreme Court criteria remain foundational, legal commentary and more recent lower court decisions suggest an evolving interpretation, particularly in response to the increasing diversification of work styles.

- A Tokyo District Court judgment in 2012, which classified remuneration paid to a part-time anesthesiologist as employment income, elaborated on the concept of "independence". It suggested that "independence" in the context of business income relates to who bears the financial risk of fluctuating revenues and expenses. The court noted that merely being able to make independent professional judgments in performing one's duties does not automatically satisfy the "independence" criterion for business income. Conversely, "subjection to an employer's direction and control" was linked to whether the object, place, and time of work are determined by others, implying that even if one makes independent professional judgments, they can still be considered under another's direction if these structural aspects of work are controlled externally.

- This 2012 decision notably distinguished between "non-independence" (primarily related to economic risk and reward) and "subordination" (related to direct control over work execution), appearing to place greater emphasis on the former ("non-independence"). It suggested that even for professions where individuals exercise independent judgment, if the structure of their work (object, place, time) is regulated by others, and their remuneration system does not reflect fluctuations in business results or direct bearing of expenses, their income is likely to be classified as employment income.

- A similar line of reasoning was seen in a 2013 Tokyo District Court case involving remuneration paid by a home tutor dispatch agency to its tutors, which was also classified as employment income. This judgment treated the criteria set forth by the 1981 Supreme Court decision as "preliminary standards" rather than rigid, necessary conditions that must all be met to establish employment income.

- Further, a 2015 Supreme Court decision (concerning debt forgiveness for directors of an unincorporated association, which was deemed employment income) explicitly referenced the criteria from the 1981 ruling, defining employment income as remuneration for labor or services provided based on an employment contract or similar arrangement, distinct from income arising from independently conducted business activities. In that case, the debt forgiveness was seen as a reward for the directors' contributions and services, thus akin to a bonus, falling under employment income.

- It has also been observed that another Supreme Court case concerning stock option exercise gains (which were classified as employment income and cited in the 2015 debt forgiveness case) did not use the specific phrasing "received from an employer" when discussing the concept of "consideration for labor".

These evolving judicial interpretations suggest a trend where the strict requirement of "subordination" for classifying income as employment income may be becoming less critical in certain contexts.

The Shifting Emphasis in Criteria

The 1981 Supreme Court judgment clearly based its distinction between business income and employment income on the twin pillars of "independence" (for business income) and "subordination" (for employment income). These criteria have been widely adopted and applied in numerous subsequent cases.

However, more recent judicial trends, particularly in lower courts, indicate a tendency to separate the analyses of "independence" and "subordination," with an increasing emphasis on "non-independence" (often viewed through the lens of economic risk, control over business results, and who bears expenses). This shift is possibly a response to the diversification of employment and service provision models in modern society, where traditional markers of "subordination" might be less apparent or diluted. Consequently, while the presence of clear subordination strongly points towards an employment income classification, its absence, especially if "non-independence" in an economic sense is evident, does not necessarily preclude such a classification today.

Broader Implications and Discussion

The 1981 Supreme Court decision, while foundational, operates within a dynamic legal landscape.

- Enduring Guidelines: The criteria articulated by the Supreme Court continue to serve as essential guidelines for taxpayers and tax authorities in distinguishing between business and employment income.

- Evolving Interpretations: The nuanced interpretations seen in more recent lower court cases reflect the judiciary's efforts to apply these principles to increasingly complex and diverse working arrangements. The greater weight given to "non-independence" (economic realities of risk and reward) over strict "subordination" (direct moment-to-moment control) acknowledges that many modern work relationships may not fit neatly into traditional employer-employee molds.

- Challenges for Modern Professionals: For independent professionals, freelancers, and participants in the gig economy, correctly classifying their income remains a significant challenge. The specific terms of their contracts, their actual working conditions, the degree of control they exercise over their work, and, importantly, how they manage financial risks and benefit from efficiencies, are all critical factors.

- Importance of Overall Economic Reality: Ultimately, the classification hinges on the overall economic reality of the relationship, rather than relying solely on labels or formal contractual terms.

The "Considerations for Discussion" in the provided commentary query the appropriateness of treating the 1981 Supreme Court's criteria merely as "preliminary standards" and the adequacy of using "non-independence" alone to determine employment income status. These questions highlight the ongoing debate and the need for clarity as work continues to evolve.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's April 24, 1981, judgment provided a clear and influential articulation of the criteria for distinguishing business income from employment income in Japan. It emphasized that business income is characterized by independence, operation for one's own account and risk, profit motive, and continuity, while employment income typically involves labor provided under an employer's direction and control, often with spatial and temporal constraints. While these principles remain central, subsequent judicial interpretations, particularly in lower courts, have shown an evolving emphasis, often looking more closely at the economic reality of "non-independence" in light of diverse and modern working styles. This ongoing development underscores the complexities of income classification in a changing economic landscape.