Burning Cars and Burning Questions: Japan's High Court Defines "Public Danger" in Arson Law

Imagine someone sets fire to a single car parked in a lot at night. Is this an act of vandalism—a case of property damage? Or is it the far more serious crime of arson? In Japanese law, the answer hinges on a single, crucial concept: whether the act created a "public danger" (kōkyō no kiken). But what does this term actually mean? Must a fire threaten to engulf a nearby building to qualify, or is the risk of it spreading to other cars sufficient?

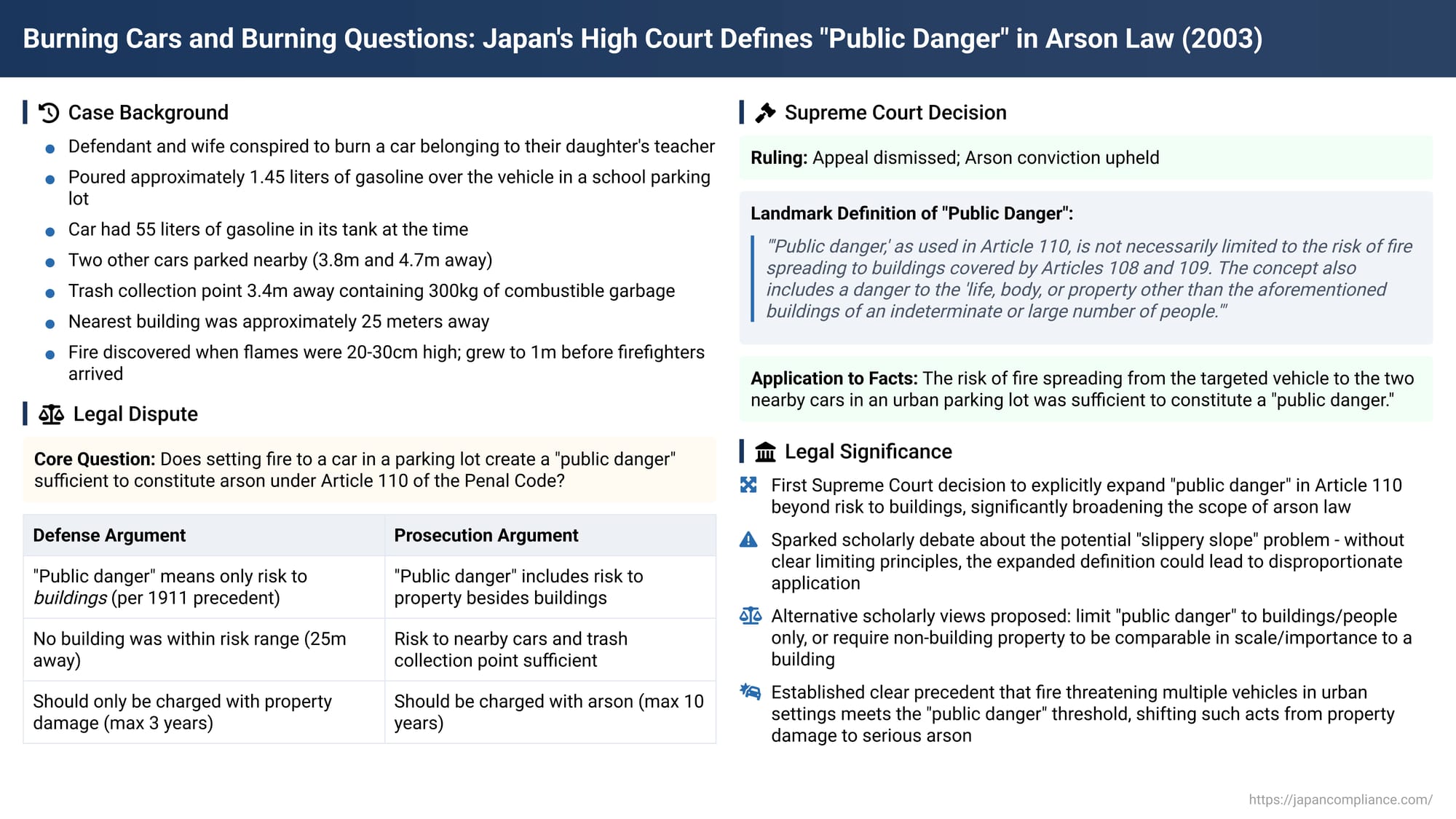

This question was at the heart of a landmark April 14, 2003, decision by the Supreme Court of Japan. In a case involving a targeted car fire in a school parking lot, the Court provided a groundbreaking definition of "public danger," officially expanding the scope of arson law in a way that sparked significant legal debate.

The Facts: A Teacher's Car in the School Parking Lot

The case unfolded on a night in a staff parking lot of an elementary school.

- The Act: The defendant and his wife conspired to set fire to a car belonging to their daughter's teacher. They approached the unoccupied vehicle, poured approximately 1.45 liters of gasoline over its body, and ignited it with a gas lighter.

- The Scene: The parking lot was situated in an urban area. It was adjacent to a park and another parking lot, and across the street from the elementary school and an agricultural co-operative building.

- The Surroundings: The targeted vehicle, which had about 55 liters of gasoline in its tank at the time, was not isolated.

- Two other cars were parked nearby: one was 3.8 meters away, and a second was another 0.9 meters beyond the first.

- A trash collection point, enclosed by a metal mesh fence and containing about 300 kg of combustible household garbage, stood 3.4 meters away.

- Crucially, the nearest building was approximately 25 meters from the targeted vehicle.

- The Result: A passerby discovered the fire while the flames were about 20 to 30 cm high. By the time firefighters arrived, the flames at the rear of the car had grown to about one meter in height. The fire damaged the target vehicle and, according to the court's findings, created a danger of spreading to the other two cars and the nearby trash collection point.

The defendant was charged with Arson of Objects Other Than Buildings (Article 110 of the Penal Code), a crime that requires the prosecution to prove that the act generated a "public danger."

The Legal Divide: Arson vs. Property Damage

The distinction between arson and property damage is not merely academic; it carries immense legal weight in Japan.

- Severity of Punishment: Arson is punished far more severely than property damage. For example, the maximum penalty for damage to an object like a car is three years in prison. The maximum penalty for arson of such an object, if it creates a public danger, is ten years.

- The Deciding Factor: The differentiating element is "public danger." If an offender burns a car in the middle of a vast, empty lot with nothing nearby to catch fire, the crime is simple property damage. If the same act creates a wider threat, it becomes the felony of arson.

The Core Legal Dispute: Defining "Public Danger"

The defendant's appeal was built on a narrow, historical interpretation of "public danger."

- The Defense's Argument: Relying on a precedent from 1911, the defense argued that "public danger" under Article 110 exclusively means a risk of fire spreading to buildings (i.e., the objects protected under the more serious arson statutes, Articles 108 and 109). Since the nearest building was 25 meters away, they contended no such danger was created.

- The Lower Court's View: The appellate court had adopted a broader definition, stating that "public danger" meant a danger to the lives, bodies, or property of an indeterminate or large number of people, and that a risk of fire spreading to property other than buildings could suffice.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Definition

The Supreme Court rejected the defendant's narrow view and used the case to issue a clear and expansive definition of "public danger" for the purposes of this crime. The Court held:

- "Public danger," as used in Article 110, is not necessarily limited to the risk of fire spreading to buildings covered by Articles 108 and 109.

- The concept also includes a danger to the "life, body, or property other than the aforementioned buildings of an indeterminate or large number of people."

- Applying this definition to the facts, the Court concluded that in an urban parking lot, the risk of fire spreading from the targeted vehicle to the two nearby cars was sufficient to constitute a "public danger."

Analysis: A Contentious Expansion and the Scholarly Debate

This decision was groundbreaking. While lower courts had previously discussed broader definitions of "public danger," this was the first time Japan's highest court explicitly affirmed an arson conviction under Article 110 based solely on the danger posed to other non-building property. The ruling immediately sparked a vigorous debate among legal scholars, who pointed out potential problems with such a broad definition.

- The "Slippery Slope" Problem: The core critique is that the Court's definition lacks a clear limiting principle. If taken literally, does a car fire that threatens to burn a few books left on a nearby park bench create a "public danger"? Such a result would seem absurd and disproportionate to the gravity of an arson charge.

- Proposed Academic Solutions: In response, scholars have proposed several alternative, more limited definitions to address this issue:

- Some argue for the narrow view the defendant proposed: "public danger" should be limited to threats to buildings or to the lives and bodies of many people, excluding danger to other property altogether.

- Others suggest a middle ground: if the danger is to property other than buildings, it should only count if that property is of a scale or importance comparable to a building.

Under these more restrictive scholarly views, the defendant in this case, where the danger was limited to two other cars, might only have been guilty of property damage.

Conclusion

The 2003 Supreme Court decision significantly clarified and broadened the scope of Japanese arson law. It definitively established that creating a fire that threatens to spread to other vehicles in an urban setting is sufficient to meet the "public danger" requirement, elevating the crime from property damage to the serious felony of arson. However, by providing a clear answer in this specific case, the Court opened a new chapter in a long-standing legal debate. The decision's broad wording continues to fuel discussion about where the precise line should be drawn, highlighting the enduring challenge of defining an abstract concept like "public danger" in a way that ensures public safety without leading to disproportionate criminal liability.