Building on the Boundary: Supreme Court Clarifies Clash Between Civil Code and Building Standards Act

Judgment Date: September 19, 1989

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench

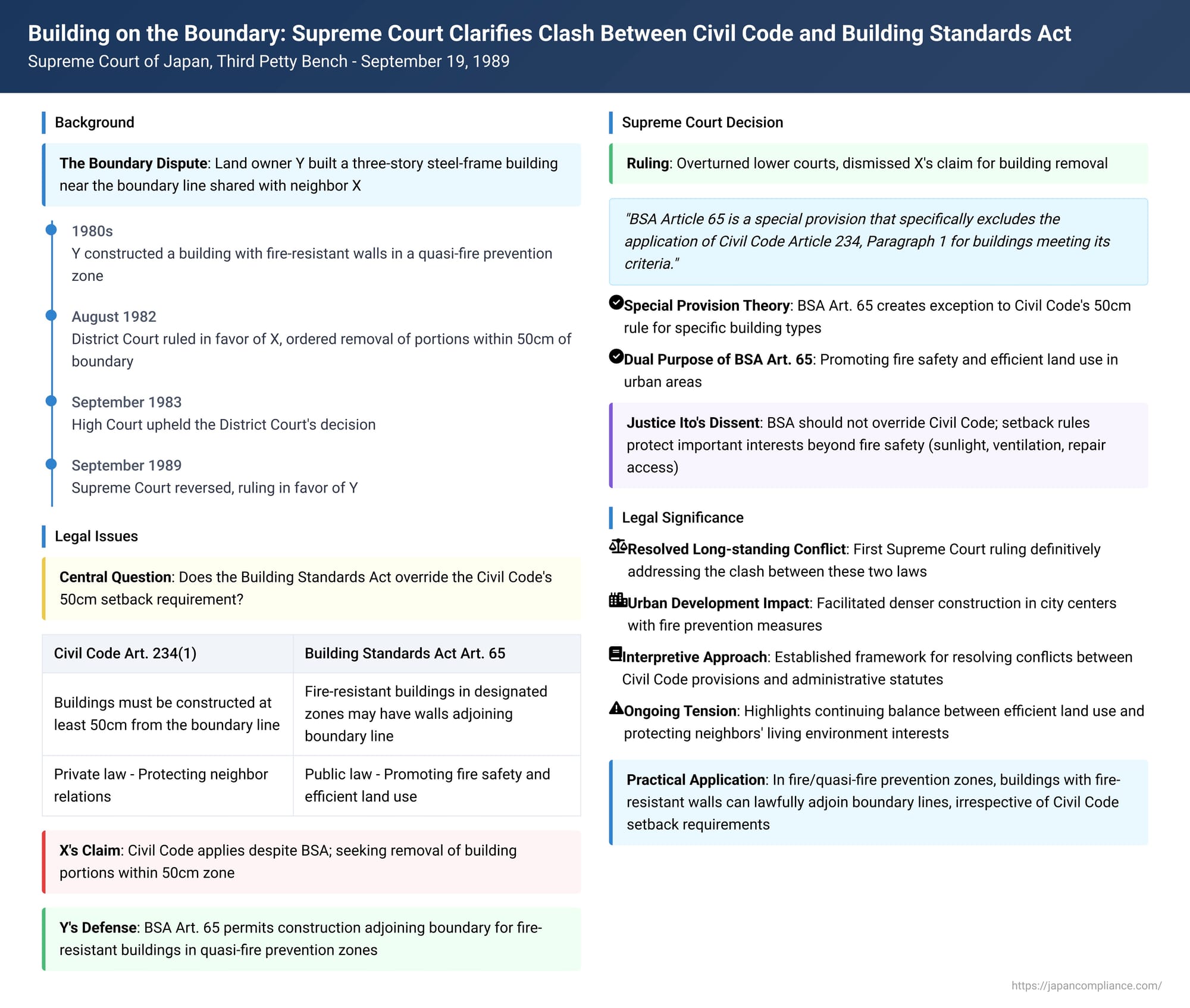

A fundamental question in property law and urban planning is how close one can build to their neighbor's land. In Japan, this issue brought two key pieces of legislation into apparent conflict: Article 234, Paragraph 1 of the Civil Code, which generally requires a 50-centimeter setback from the boundary line, and Article 65 (now Article 63) of the Building Standards Act (BSA), which permits certain fire-resistant buildings in designated zones to be constructed right up to the boundary. A 1989 Supreme Court decision tackled this conflict head-on, providing a landmark interpretation that continues to shape building practices in Japan.

The Boundary Dispute: A Neighbor's Challenge

The case arose when Y, a landowner, commenced construction of a three-story steel-frame building on his property. He proceeded without seeking the consent of X, the owner of the adjacent land. X observed that the new building was being erected very close to the northern boundary line shared by their properties.

Believing this to be a violation of his rights, X filed a lawsuit against Y. X's claim was based on Article 234, Paragraph 1 of the Civil Code, which stipulates that a building must be constructed at a distance of at least 50 centimeters from the boundary line. X demanded the removal of the portions of Y's building that encroached within this 50-centimeter zone.

Y mounted a defense based on the Building Standards Act. He argued that his property was located within a designated "quasi-fire prevention zone" (準防火地域 - jun-bōka chiiki). Furthermore, the exterior wall of his building facing X's property was of fire-resistant construction. Under these conditions, Y contended, Article 65 of the BSA (the provision number at the time of the case, later renumbered to Article 63) specifically permitted him to build the exterior wall adjoining the boundary line, thereby overriding the Civil Code's setback requirement. It was also noted as a fact that no local custom existed in the area that would permit mid-rise buildings to be constructed less than 50 centimeters from a boundary line not abutting a public road.

Lower Courts: Siding with the Civil Code Setback

The lower courts found in favor of X, the plaintiff seeking the setback.

- The Osaka District Court (First Instance), in its judgment on August 30, 1982, held that BSA Article 65 did not automatically displace the Civil Code's 50cm setback rule, even for buildings meeting the BSA's criteria (fire-resistant wall in a fire prevention or quasi-fire prevention zone). The court reasoned that BSA Article 65 would only take precedence over Civil Code Article 234(1) if there was a compelling "rational reason" to permit construction up to the boundary, even if it meant sacrificing the neighboring landowner's interests typically protected by the Civil Code (such as access to light and ventilation, and convenience for future construction or repair on their own land). Such rational reasons might include a mutual agreement between the neighbors or a recognized local custom allowing such construction (as per Civil Code Article 236). Since no such overriding reasons were found in Y's case, the District Court upheld X's claim for removal.

- The Osaka High Court (Appeal Court), on September 6, 1983, dismissed Y's appeal, concurring with the District Court's reasoning. Y then appealed this decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Decision: BSA Provision Takes Precedence

In a significant turn, the Supreme Court overturned the lower courts' decisions. It quashed both the High Court and District Court judgments that had favored X and ultimately dismissed X's claim for removal of the building portions. The majority opinion of the Supreme Court established a clear hierarchy between the two laws in this specific context.

BSA Article 65 as a "Special Provision" to the Civil Code:

The Supreme Court interpreted BSA Article 65 (which states that in fire prevention or quasi-fire prevention zones, a building with fire-resistant exterior walls may have those walls built adjoining the boundary line) as a "special provision" (tokusoku) that specifically excludes the application of Civil Code Article 234, Paragraph 1 for buildings that meet its criteria.

Rationale: Fire Safety and Efficient Land Use:

The Court provided the following reasoning for its interpretation:

- Purpose of BSA Article 65: The provision was understood to regulate the relationship between adjoining landowners (sōrin kankei) with two primary objectives in mind:

- Promoting fire safety by encouraging the use of fire-resistant exterior walls.

- Facilitating the rational and efficient use of land in designated fire prevention or quasi-fire prevention zones, which are often urban areas where land is scarce.

- Interpretation of BSA Article 65's Nature: The Court explained why this interpretation was necessary:

- Not a Building Confirmation Standard Itself: The wording of BSA Article 65 does not, on its own, establish technical standards to be reviewed during the building confirmation (建築確認 - kenchiku kakunin) process under BSA Article 6, Paragraph 1 (which mandates that building plans conform to the BSA and related laws). A 1980 Supreme Court precedent had already established that compliance with Civil Code Article 234(1) is not, in itself, a matter for review during the building confirmation process.

- No General BSA Setback Rule to be an Exception To: The BSA and other related laws do not contain a general, overriding principle that dictates a specific minimum distance between exterior walls and boundary lines in fire prevention or quasi-fire prevention zones that would serve as a baseline standard for building confirmation. (The BSA, for instance, does have a specific setback requirement for first-category exclusive low-rise residential zones in Article 54, but this is a specific rule, not a general one applicable to fire zones). Therefore, BSA Article 65 cannot be viewed as an exception that relaxes some other, more general, building confirmation standard within the BSA itself.

- Finding Meaning as a Special Provision: Consequently, the Supreme Court reasoned that BSA Article 65 only acquires a distinct and logical regulatory meaning if it is interpreted as a special provision that carves out an exception to the general rule set by Civil Code Article 234, Paragraph 1 (which requires the 50cm setback).

Applying this interpretation to the facts, since Y's land was in a quasi-fire prevention zone and his building featured a fire-resistant exterior wall, the Supreme Court concluded that BSA Article 65 permitted the construction even within the 50-centimeter zone that would otherwise be mandated by the Civil Code.

Justice Ito's Dissent: Prioritizing Neighboring Rights and Environmental Concerns

The decision was not unanimous. Justice Masami Ito provided a strong dissenting opinion, arguing that BSA Article 65 should not be considered a special provision overriding Civil Code Article 234(1). His key points included:

- Different Natures of the Laws: Civil Code Article 234(1) is a private law provision designed to adjust rights and relationships between private adjoining landowners. The Building Standards Act, in contrast, is primarily a public law statute that sets minimum standards for building construction, structure, equipment, and use from the perspective of public interest and safety. It generally regulates from a public law standpoint and does not alter private rights unless it explicitly states an intention to do so.

- No Explicit Override in BSA Article 65: BSA Article 65 merely states that such construction "can be done" (設けることができる - mōkeru koto ga dekiru); it does not explicitly state that it overrides the Civil Code provision. It is situated amongst other public law regulations pertaining to building confirmations.

- Substantive Protections of Civil Code Article 234(1): Justice Ito emphasized that the Civil Code's setback rule serves several important purposes beyond just fire prevention:

- It prevents a "first-come, first-served" scenario where one owner building right up to the boundary could impede the neighbor's ability to construct or repair their own building, a practical necessity that remains relevant even with modern construction techniques.

- It helps secure essential "living environment interests" such as sunlight, ventilation, and general access for both neighbors.

He argued it was inappropriate to sacrifice these broad interests solely for fire prevention and land efficiency, even in designated fire zones.

- Concerns about Widespread Zone Designations: Justice Ito expressed concern about the practical application of the majority's view. Fire prevention and quasi-fire prevention zones are not limited to high-risk commercial or industrial areas. They are also designated in residential areas, including second-category exclusive residential zones intended to protect good living environments. If such a residential area, which might traditionally have had no custom of building directly on the boundary line, is designated as a fire or quasi-fire prevention zone, the majority's interpretation would immediately permit construction up to the boundary, thereby eroding the existing environmental quality and protections for residents. He even noted the possibility of such designations extending to first-category exclusive low-rise residential zones.

- Rational Land Use Reconsidered: He contended that rational and efficient land use in modern times increasingly calls for securing open spaces while potentially allowing for taller, more concentrated building development, rather than simply permitting structures to be built right up to every boundary line in designated zones. He suggested that allowing such close construction might even be counterproductive to true rational land use.

Understanding the Legal Landscape

This Supreme Court decision was the first to definitively rule on the long-debated conflict between BSA Article 65 (now 63) and Civil Code Article 234(1). It endorsed what legal scholars refer to as the "Special Provision Theory" (tokusoku setsu).

- The Special Provision Theory: This theory, now the majority view supported by the Supreme Court, holds that BSA Article 63 (formerly 65) functions as a specific exception to the general rule in Civil Code Article 234(1). If a building meets the conditions of BSA Article 63 (i.e., it has fire-resistant exterior walls and is located in a fire prevention or quasi-fire prevention zone), then the 50cm setback requirement of the Civil Code is excluded. The building can legally adjoin the boundary line without the neighbor's consent or a specific local custom permitting it. Proponents of this theory often point to the historical development of building regulations, arguing that Civil Code Article 234(1) originated in an era of wooden buildings and that modern fire-resistant construction in dense urban areas necessitates exceptions for efficient land use. The Urban Areas Building Act of 1919, a predecessor to the BSA, is cited as having intended to encourage fire-resistant construction by relaxing the Civil Code's setback rules as an incentive.

- The Non-Special Provision Theory (hi-tokusoku setsu): This theory, reflected in Justice Ito's dissent and the lower court rulings, argues that BSA Article 63 and Civil Code Article 234(1) operate independently. Even if a building meets the BSA Article 63 criteria (making it permissible from a public regulatory standpoint), it would still need to comply with the Civil Code's 50cm setback requirement under private law unless the adjoining landowner consents or a local custom allows otherwise. This view stresses the different purposes of the two laws—public safety regulation versus private rights adjustment—and the broader range of neighborly interests protected by the Civil Code.

Implications for Building Practices:

Based on the Supreme Court's adoption of the Special Provision Theory:

- In fire prevention or quasi-fire prevention zones, buildings with fire-resistant exterior walls can be lawfully constructed adjoining the boundary line, irrespective of Civil Code Article 234(1).

- However, this does not mean all other BSA regulations concerning building placement are waived. Other BSA provisions that directly or indirectly regulate the distance of building walls from boundary lines or site boundaries—such as setback rules in specific residential zones (e.g., BSA Art. 54), regulations on wall alignment (BSA Art. 46), floor-area ratios (BSA Art. 52), building coverage ratios (BSA Art. 53), building height restrictions (BSA Art. 56), and regulations concerning shadows cast by mid-to-high-rise buildings (BSA Art. 56-2)—continue to apply to these buildings.

- For buildings that do not meet the criteria of BSA Article 63 (e.g., they are not in a designated fire zone, or their walls are not fire-resistant), the Civil Code Article 234(1) setback requirement remains fully applicable under private law, in addition to any relevant BSA regulations.

Legal commentators have noted that this Supreme Court decision exemplifies an interpretive approach where, in cases of apparent conflict between Civil Code provisions and administrative statutes, courts should endeavor to clarify the distinct purposes, objectives, and functions of the legal mechanisms within each law and then determine their specific application to the legal relationship at hand.

Conclusion: The Ongoing Dialogue Between Public Regulation and Private Property Rights

The 1989 Supreme Court judgment brought clarity to a significant point of interaction between public building regulations and private property rights concerning building setbacks. By establishing BSA Article 63 (then 65) as a special provision overriding the Civil Code's general setback rule in specific circumstances, the Court prioritized objectives of fire safety and efficient urban land utilization in designated zones. However, Justice Ito's compelling dissent highlights the enduring tension and the important living environment interests that also warrant consideration. The decision remains a critical reference for architects, developers, and property owners navigating the complex web of rules that govern construction in Japan's densely populated landscape.