Building Illegally, Seeking Payment: A Supreme Court Look at Contracts Against Public Order

Judgment Date: December 16, 2011

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench

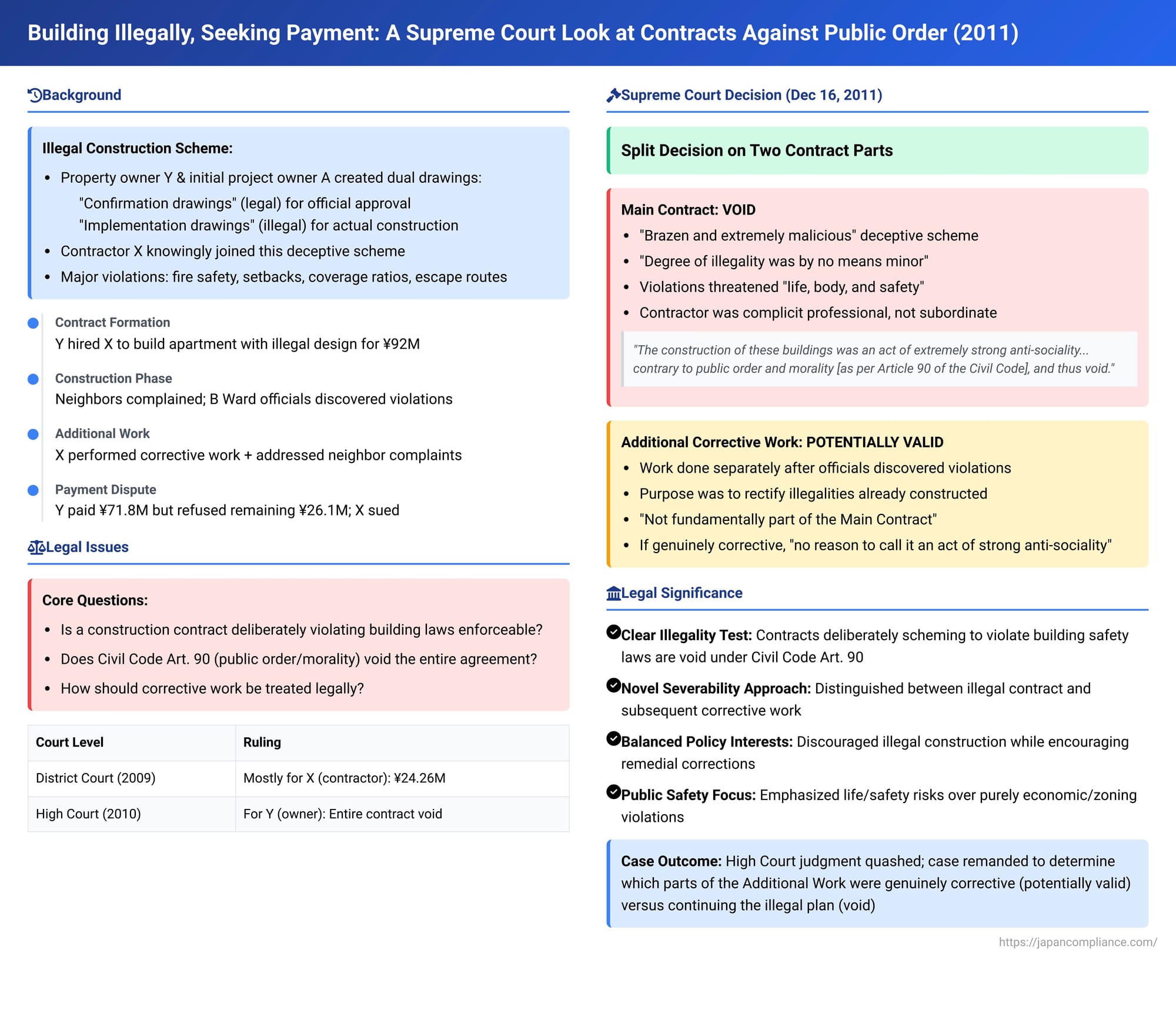

What happens when a construction contract is entered into with the explicit intention of violating building laws and deceiving authorities? Is such a contract enforceable? And what if, during the project, additional work is done, some of which aims to correct the very illegalities initially planned? A 2011 Japanese Supreme Court decision tackled these thorny issues, offering a nuanced perspective on contracts that offend public order and morality.

The Illicit Plan: Building an Apartment by Deception

The case originated from a plan to construct a rental apartment building. The initial project owner, A, and the property owner, Y (the defendant in this Supreme Court case), recognized that strictly adhering to the Building Standards Act and other regulations would limit the number of rentable units, making the project less profitable. They therefore decided to proceed with a plan to construct an illegal building.

Their scheme was elaborate:

- Two sets of architectural drawings were prepared: "confirmation drawings" that complied with all legal requirements, intended for the official building confirmation application, and "implementation drawings" detailing the actual, non-compliant structure to be built.

- The plan was to first obtain a building confirmation certificate and an inspection certificate based on the compliant confirmation drawings. Then, after these official approvals were secured, the building would be altered or completed according to the illegal implementation drawings.

- The planned illegalities were significant, involving violations of fire-resistance regulations, northern setback rules (protecting neighbors' light), sunlight access restrictions for neighboring properties, building coverage ratio limits, floor area ratio limits, and minimum width requirements for emergency escape routes.

Y, the property owner, subsequently entered into a construction contract ("the Main Contract") with X, a construction contractor (the plaintiff/appellant, whose bankruptcy trustee later took over the appeal). The agreed price for the main construction was 92 million yen. X was fully briefed on the illegal scheme devised by A and Y, including the discrepancies between the two sets of drawings and the intended violations of law. X knowingly agreed to this plan. The Main Contract itself incorporated elements of the illegal design from the outset, such as an unauthorized basement, as per the implementation drawings.

X commenced construction after the official building confirmation certificate (based on the compliant confirmation drawings) was issued. However, the illegal construction did not go unnoticed. Following complaints from residents living near the construction site, officials from Tokyo's B Ward conducted an on-site investigation. This revealed that the ongoing work significantly deviated from the approved confirmation drawings.

As a consequence of this discovery, X was compelled to undertake corrective work to rectify some of the illegal structures already built. Additionally, X had to address various complaints from neighbors, which necessitated further additional and modified construction work (collectively referred to as "the Additional Work"). After all construction, including the Additional Work, was completed, X handed the buildings over to Y.

Y paid a total of 71.8 million yen towards the construction costs but refused to pay the remaining balance. X then filed a lawsuit to recover a portion of the outstanding amount, over 26.1 million yen, which included costs for both the original Main Contract work and the subsequent Additional Work.

Legal Challenges and Lower Court Rulings

- The Tokyo District Court (First Instance), on March 27, 2009, largely ruled in favor of the contractor, X, ordering the property owner, Y, to pay over 24.26 million yen.

- However, the Tokyo High Court (Appeal Court), on August 30, 2010, reversed this decision and dismissed X's claim entirely. The High Court's primary reasoning was that "a construction contract for a specific building, if it intentionally infringes upon the interests of third parties in a malicious manner and is utterly unacceptable from the standpoint of social decency, must also be denied legal effect under private law." Essentially, the High Court found the entire contractual arrangement to be void.

X (via his bankruptcy trustee) appealed this decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Judgment: A Tale of Two Contracts (or Parts Thereof)

The Supreme Court, on December 16, 2011, quashed the High Court's judgment (which had dismissed all of X's claims) and remanded the case back to the High Court for further consideration, specifically concerning the costs associated with the Additional Work. The Supreme Court agreed with the High Court that the Main Contract was void, but found that the agreement for the Additional Work might, in part, be valid.

1. The Main Contract: Void for Offending Public Order (Civil Code Art. 90)

The Supreme Court was unequivocal in condemning the original Main Contract:

- Malicious Intent: The contract was entered into with the clear objective of building illegal structures. The method involved a deliberate plan to circumvent the Building Standards Act's confirmation and inspection processes by using deceptive dual drawings to fraudulently obtain official certificates. The Court described this plan as "brazen and extremely malicious."

- Severity of Illegality: If the buildings had been completed according to the illegal implementation drawings, they would have numerous serious violations. These included not only breaches of zoning rules (like setback, sunlight, and density limits) but also critical safety violations related to fire-resistant construction and the width of emergency escape routes. Such violations posed a direct risk to the "life, body, and safety of residents and neighbors." Many of these illegalities would have been exceedingly difficult, if not impossible, to correct once the buildings were finished. The Court concluded that the "degree of illegality was by no means minor."

- Contractor's Complicity: While X, the contractor, did not actively propose the illegal construction scheme, he was a professional in the construction business. He was fully aware of the "brazen and extremely malicious plan" and knowingly agreed to it when entering into the Main Contract. The Court found no evidence suggesting that X was in a position where it was difficult for him to refuse Y's request to build illegally, meaning X could not be seen as being in a "clearly subordinate position" to Y.

Given these factors, the Supreme Court declared that "the construction of these buildings was an act of extremely strong anti-sociality," and therefore, the Main Contract aiming at this objective was "contrary to public order and morality [as per Article 90 of the Civil Code], and thus void." The Court thus upheld the High Court's dismissal of X's claim for payment under the Main Contract.

2. The Additional (Corrective) Work: Potentially Valid in Part

The Supreme Court took a different view regarding the Additional Work. It reasoned:

- Separate Nature: The Additional Work appeared to have been agreed upon and executed separately after the main construction had commenced and in response to new circumstances, namely the corrective instructions from the B Ward officials and the complaints from neighbors. Importantly, this Additional Work included measures to rectify illegal parts that had already been constructed under the (now void) Main Contract.

- Not Inherently Part of the Illegal Plan: Because of its nature and timing, the Additional Work could "not fundamentally be considered part of the Main Contract."

- Distinguishing Purpose: If any part of the Additional Work involved merely modifying some of the originally planned illegal construction without actually rectifying the illegality, then that specific part would be subject to a different evaluation (and could also be deemed void).

- Presumptive Validity of Corrective Work: However, if the Additional Work was genuinely aimed at correcting illegalities or involved changes unrelated to perpetuating the original illegal design, then "there is no reason to call it an act of strong anti-sociality." Consequently, an agreement for such corrective or neutral Additional Work "cannot be said to be contrary to public order and morality."

Because the High Court had not sufficiently distinguished between the Main Contract and the Additional Work, nor had it clarified the specific nature and purpose of each component of the Additional Work, the Supreme Court remanded this part of the case for further factual determination and legal assessment.

Deeper Dive: Legal Principles at Play

This case navigates the complex interaction between administrative regulations (like building codes) and private contract law, particularly the application of Civil Code Article 90, which voids legal acts contrary to public order and morality.

Public Order and Morality (Civil Code Art. 90) vs. Illegal Contracts:

The question of whether a contract that violates an administrative statute is automatically void under private law is a classic one.

- Older Approach: Japanese law historically sometimes distinguished between "mandatory provisions" (kyōkō kitei, or more specifically, 効力規定 - kōryoku kitei, meaning provisions affecting validity) and mere "regulatory provisions" (torishimari kitei). Violating a mandatory provision might nullify a contract, while breaching a regulatory one might only lead to administrative sanctions without affecting the contract's private law validity. For example, older cases held contracts violating wartime price controls void, while a contract by an unlicensed food vendor might be deemed valid.

- Modern Prevailing Approach: More recent jurisprudence, including this Supreme Court decision, tends not to rely on such rigid classifications of statutes. Instead, courts typically assess the validity of a contract that contravenes administrative regulations by applying the general principle of Civil Code Article 90 (public order and morality). This involves a case-by-case analysis considering factors such as the maliciousness of the contract's purpose, the gravity of the illegality, the potential harm to public interests or third parties, and the subjective circumstances and intentions of the contracting parties. This judgment, in voiding the Main Contract, exemplifies this comprehensive approach by weighing the deceptive scheme, the safety risks, and the contractor's knowing participation.

The "Novel" Aspect: Severing and Saving Corrective Actions:

A particularly noteworthy aspect of this decision is the Supreme Court's willingness to conceptually sever the agreement for the Additional Work (especially the parts aimed at rectifying illegalities) from the void Main Contract and consider its potential validity. This is described by legal commentators as "novel."

- Traditional Voiding of Entire Contracts: Precedents involving contracts against public order (e.g., those related to gambling debts, usurious loans, or contracts for illegal services) have generally treated the entire contract as void. Partial validity has typically been recognized only in limited circumstances, such as where a contract is quantitatively divisible (e.g., a sale exceeding a price control limit might be held valid up to the controlled price) or where the element offending public order can be cleanly and easily separated without rewriting the parties' core agreement.

- Focus on Rectification: The Supreme Court's rationale here seems to be driven by the purpose of the Additional Work. While voiding the Main Contract prevents the realization of its illegal objectives, potentially validating the corrective portions of the Additional Work serves to eliminate the illegal state of affairs created by the initial construction. This aligns with the underlying spirit of the law, which aims to prevent and rectify illegalities.

- Separate Agreement?: The Supreme Court referred to the Additional Work as being based on a "separate agreement." Some commentators noted that the High Court hadn't explicitly found a distinct new contract for this work, raising technical questions about the scope of the Supreme Court's review (which is generally limited to points of law, not fact-finding). However, the emphasis is on the purpose of this later work being distinct from the original illegal intent.

Consequences of Voiding Contracts and "Acts for an Illegal Cause":

When a contract is void for being against public order, and performance has already occurred, Civil Code Article 708, concerning "acts for an illegal cause" (fuhō gen'in kyūfu), often comes into play. This article generally prohibits the party who provided the performance from demanding its return.

- In the context of this case, if the Main Contract was entirely void, the contractor X's delivery of the (partially illegal) building could be seen as an act for an illegal cause. This would mean X could not demand the building's return, and the owner Y would effectively get to keep it.

- If X also could not claim any payment for the work done under the void Main Contract, this would be a harsh outcome for X. However, Y had already paid a significant portion of the contract price (71.8 million out of 92 million yen). This payment by Y could also be considered an act for an illegal cause, meaning X would not be obliged to return it. The High Court, in dismissing all of X's claims, might have implicitly considered this a rough form of justice.

Broader Implications for Law and Social Order:

Legal commentators have highlighted two broader theoretical perspectives relevant to such cases:

- Market Order as "Public Order": This view emphasizes the state's role in actively ensuring the proper functioning of the market. It suggests that contracts violating economic regulations designed to protect market integrity (e.g., consumer protection laws, financial transaction laws, anti-monopoly laws) should be more readily deemed void. This perspective would likely support the Supreme Court's approach of upholding corrective actions taken in response to administrative intervention (by B Ward).

- Constitutional Rights and Private Law: This approach stresses the state's duty not only to refrain from violating fundamental constitutional rights but also to actively protect and support their realization, even in private dealings. Interventions in private contractual freedom could be justified to prevent harm to fundamental rights (e.g., safety, health, environmental rights of residents and neighbors). This view would see the Supreme Court's decision (particularly in potentially validating work that rectifies safety hazards and addresses infringements like sunlight obstruction) as the state fulfilling its "duty to protect fundamental rights."

Conclusion: Upholding Legal Compliance While Allowing for Rectification

The 2011 Supreme Court decision provides a significant clarification on how Japanese law deals with construction contracts deliberately designed to violate building codes. It robustly affirms that agreements with such a "brazen and extremely malicious" illegal purpose are void as contrary to public order and morality. However, in a novel and pragmatic turn, the Court opened the door for recognizing the validity of subsequent, separate agreements for work aimed at rectifying those illegalities or addressing ensuing problems. This approach seeks to prevent parties from profiting from blatantly illegal schemes while also encouraging and allowing for the correction of unlawful situations, ultimately aiming to uphold both legal compliance and public safety. The remand to the High Court would focus on carefully dissecting the Additional Work to determine which parts, if any, shared the original illegal taint and which were genuinely corrective or otherwise legitimate.