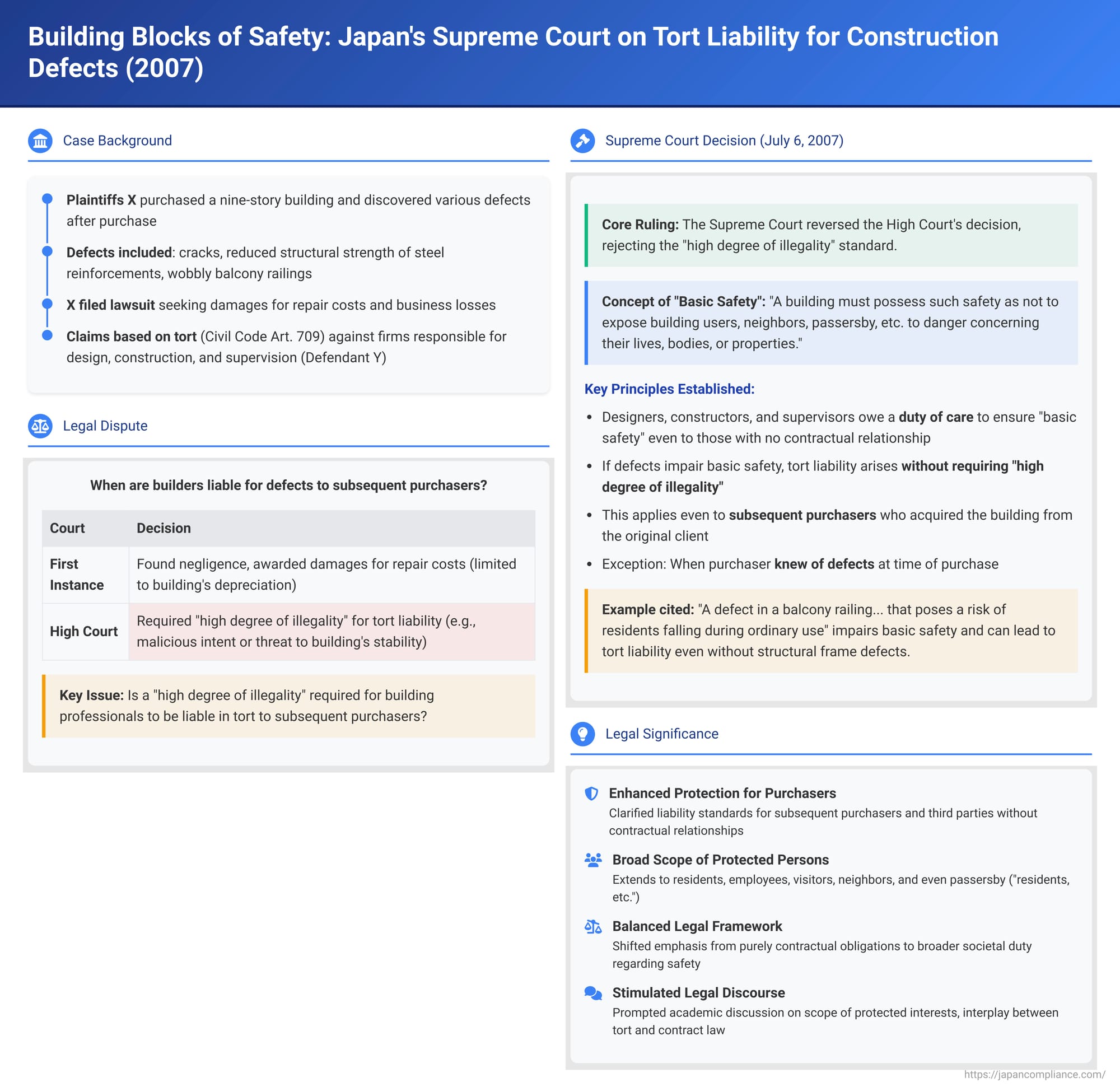

Building Blocks of Safety: Japan's Supreme Court on Tort Liability for Construction Defects

When a newly constructed or existing building reveals defects, especially those compromising its safety, who bears the responsibility? This question becomes particularly complex when the injured parties are not the original clients who contracted for the building's construction, but subsequent purchasers or even users and neighbors. On July 6, 2007, the Supreme Court of Japan delivered a significant judgment in a Damages Claim Case (Heisei 17 (Ju) No. 702), establishing a crucial precedent regarding the tort liability of building designers, constructors, and supervisors for ensuring a building's "basic safety".

The Defective Building: A Case Overview

The case involved two individuals, Plaintiffs X, who had purchased a nine-story building intended for both residential and commercial use from a non-party, A. After the purchase, X discovered various defects in the building. These included cracks, reduced structural strength of steel reinforcements, and, according to X's claims, issues like wobbly balcony railings.

Believing these defects compromised the building's integrity and value, Plaintiffs X filed a lawsuit seeking damages for repair costs and associated business losses. Their claim, relevant to this Supreme Court decision, was based on tort (under Article 709 of the Civil Code) against the firms responsible for the building's construction, design, planning, and works supervision (collectively referred to as Defendant Y).

Lower Courts at Odds: The "Degree of Illegality"

The journey of the case through the lower courts revealed differing views on the threshold for tort liability in such situations:

- First Instance Court: This court found negligence on the part of Defendant Y. It acknowledged that defects affecting the building's durability necessitated reinforcement and awarded damages for repair costs, albeit limited to the extent of the building's depreciation.

- Appellate Court (High Court): The High Court took a much stricter stance. It overturned the first instance court's decision that had found Y liable. The High Court held that for tort liability to arise from construction defects, a "high degree of illegality" was required. This would involve, for example, malicious intent on the part of the builders or defects so severe that the very existence or stability of the building was threatened. Finding these conditions unmet, it dismissed X's claims against Y.

Plaintiffs X appealed this decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Ruling (July 6, 2007): Prioritizing Basic Safety

The Supreme Court largely disagreed with the High Court's stringent requirements and, in a pivotal part of its judgment, reversed the dismissal of the tort claim, remanding it for further consideration. The Court laid down clear principles regarding the responsibility of building professionals:

- Core Principle: "Basic Safety" of Buildings: The Court began by emphasizing the fundamental role of buildings in society. Buildings are utilized by a diverse range of people—residents, employees, visitors—and exist in proximity to other buildings, roads, and public spaces. Therefore, the Court declared, "a building must possess such safety as not to expose these building users, neighbors, passersby, etc. (hereinafter collectively referred to as 'residents, etc.') to danger concerning their lives, bodies, or properties". This level of safety was termed "basic safety as a building" (tatemono toshite no kihonteki na anzensei).

- Duty of Care Owed by Building Professionals: Based on this premise, the Court established that "designers, constructors, and works supervisors (hereinafter collectively referred to as 'designers/constructors, etc.') involved in the construction of a building bear a duty of care, even in relation to residents, etc., with whom they have no contractual relationship, to take due consideration so that the said building does not lack basic safety as a building". A failure to exercise this due consideration constitutes a breach of this duty of care, amounting to negligence.

- Tort Liability for Breach: The Court then linked this duty to tort liability: "If designers/constructors, etc., neglect this duty, and as a result, a building is constructed with defects that impair its basic safety as a building, thereby infringing upon the lives, bodies, or properties of residents, etc., then the designers/constructors, etc., shall be liable for damages arising therefrom under tort." This liability applies "unless there are special circumstances, such as the person asserting the tort claim having purchased the said building with prior knowledge of the said defects and on that premise". The Court explicitly stated that this principle holds true even if the "residents, etc." are subsequent purchasers who acquired the building from the original client who commissioned its construction.

- Rejection of the "High Degree of Illegality" Standard: The Supreme Court directly refuted the High Court's position that tort liability is confined to cases involving a "high degree of illegality". The judgment stated: "If a building has defects that impair its basic safety as a building, tort liability should be deemed to arise, and there is no reason to hold that tort liability is recognized only in cases where the illegality is of a high degree".

- To illustrate, the Court offered an example: "A defect in a balcony railing, for instance, could be such that it poses a risk of residents, etc., falling during ordinary use, thereby endangering their lives or bodies. If such a defect exists, it should be said that the building has a defect impairing its basic safety as a building, and there is no reason to hold that tort liability is recognized only when there are defects in the building's foundation or structural frame".

Unpacking "Basic Safety" and Its Implications

The Supreme Court's introduction and emphasis on "basic safety" have several important dimensions:

- Meaning of "Basic Safety": The term refers to the fundamental level of safety necessary to ensure that a building does not pose a danger to the lives, bodies, or properties of those who use it or are in its vicinity. Whether a building meets this standard is not merely a subjective assessment but is to be judged based on objective criteria, including applicable laws, regulations, and prevailing societal norms regarding safe construction. The term "basic" itself does not lead to a specific legal conclusion but rather denotes a foundational safety level that must not be compromised.

- Scope of Protected Persons: The duty to ensure basic safety extends to a broad category of individuals described as "residents, etc.". This includes not only the building's occupants (residents, employees) and visitors but also neighbors and even passersby who might be affected by the building's lack of safety. This significantly expands the scope of potential claimants beyond those in direct contractual privity with the building professionals.

- Nature of Compensable Harm: The Court specified that the harm must be to "life, body, or property". While purely mental or emotional distress, unaccompanied by physical injury or property loss, is generally excluded from this direct protection, the concept of "property" damage can be interpreted broadly. For instance, the financial cost incurred to repair defects and restore basic safety can be considered damage to property. Some scholars argue that the very state of having to live or conduct business in an unsafe building is an infringement of a property interest in a safe environment, or that expenses incurred to mitigate danger (like a passerby buying a helmet due to fear of falling debris from a poorly maintained building) could potentially be claimed as property damage, subject to tests of illegality or foreseeability.

Significance and Impact of the Ruling

This 2007 Supreme Court decision has had a considerable impact on construction-related law and practice in Japan:

- Clarifying Liability Standards: It provided a more unified and accessible standard for tort claims against building professionals by subsequent purchasers and other affected third parties. By rejecting the "high degree of illegality" requirement, the Court made it clear that fundamental safety failures are sufficient grounds for liability, without needing to prove extraordinary circumstances like fraudulent intent or imminent collapse.

- Responding to Societal Needs: The judgment was seen as a response to growing societal concern over building safety and quality. It offered enhanced protection, particularly for purchasers of existing or "used" homes, who might otherwise have limited recourse for latent defects not covered by contractual warranties with their immediate seller.

- Stimulating Legal Discourse: The decision has prompted significant academic discussion on fundamental aspects of tort law, including the precise scope of protected interests (especially "property"), the interplay between tort law and contract law (particularly warranties), and the overall role of tort law in ensuring public safety and quality standards. The debate includes how to conceptualize repair costs—as compensation for diminished value, as direct property loss due to expenditure, or as restoration of a "property right" to a safe building.

The Evolving Landscape of Construction Liability

The Supreme Court's focus on "basic safety" as a cornerstone of tort liability for building professionals represents a key development. It shifts the emphasis from purely contractual obligations to a broader societal duty.

- Tort vs. Contract: While contractual warranties between a builder and the first owner play a role, this ruling confirms a distinct tort-based duty that extends to subsequent owners and third parties, focused on preventing harm from fundamental safety defects.

- Liability for Others in the Chain?: The PDF commentary suggests that the principle could potentially be considered for others involved in a building's lifecycle beyond the initial designers and constructors, though this would involve careful balancing of interests.

- Beyond Basic Safety?: There is ongoing debate among legal scholars about whether this tort liability for designers and constructors is strictly limited to defects that impair "basic safety" or if it could extend to other significant defects that don't necessarily pose immediate physical danger but severely affect usability or value.

- Who Can Claim?: The term "residents, etc." is broad and can even include the original client who commissioned the building if they suffer harm due to a breach of this basic safety duty, separate from their contractual claims.

Conclusion

The Japanese Supreme Court's 2007 decision in this case marked a significant affirmation of the legal responsibilities of building designers, constructors, and supervisors. By establishing the principle of "basic safety," the Court underscored that these professionals have a fundamental duty, extending beyond their contractual relationships, to ensure that buildings do not pose a danger to the lives, bodies, or properties of a wide range of individuals. This ruling prioritizes the safety of building occupants and the public, making it clear that liability for critical safety defects does not require proof of extreme negligence or malicious intent, but rather a failure to meet this foundational standard of care.