Bringing It Back: Mortgagee's Right to Recover Removed Factory Assets in Japan

Date of Judgment: March 12, 1982

Case Name: Claim for Delivery of Goods, etc.

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench

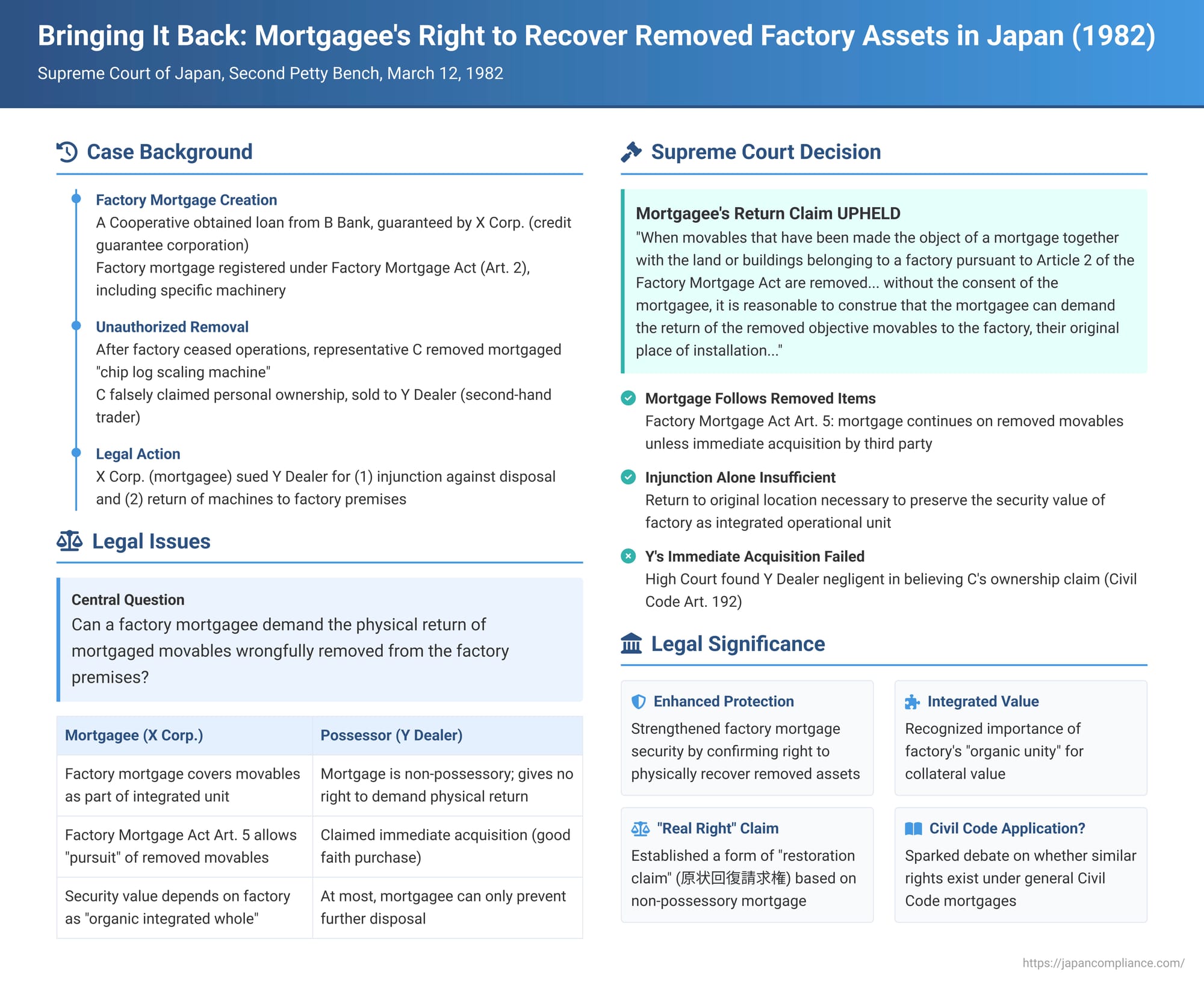

In Japan, the "Factory Mortgage Act" (kōjō teitōhō) provides a specialized legal framework allowing factories to be mortgaged as a single operational unit, encompassing not just the land and buildings but also designated machinery and equipment installed therein. This is crucial for industrial financing, as the value of a factory often lies in its integrated operational capacity rather than its components sold piecemeal. A key question arises if machinery or equipment specifically included in such a factory mortgage is wrongfully removed from the premises. Can the mortgagee compel its return? The Supreme Court of Japan addressed this issue in a significant judgment on March 12, 1982, affirming the mortgagee's right to demand the restoration of such removed assets.

The Facts: A Factory Mortgage, Unauthorized Sale, and a Mortgagee's Action

The case involved a credit guarantee corporation (the mortgagee) seeking to protect its security interest in factory assets:

- The Factory Mortgage: A Coop., a cooperative engaged in manufacturing wood chips, obtained a loan from B Bank. This loan was guaranteed by X Corp., a prefectural credit guarantee corporation. To secure X Corp. against its potential liability under the guarantee, A Coop. created a root mortgage (neteitōken) over its factory. This mortgage, established under Article 2 of the Factory Mortgage Act, covered A Coop.'s real property (land and buildings) and, importantly, also specific movable assets located within the factory, including a "chip log scaling machine" (the "Movables"). The mortgage was duly registered, and an official inventory listing the mortgaged movables was submitted as required by the then-Article 3 of the Factory Mortgage Act.

- Unauthorized Removal and Sale: After A Coop.'s factory ceased operations, C, who was the representative of A Coop., took the Movables from the factory. Claiming that the Movables were his personal property, C sold them to Y Dealer, a trader in second-hand goods (kobutsu-shō). Y Dealer took possession of the Movables, which were thus removed from the factory premises.

- X Corp.'s Lawsuit: X Corp., as the factory mortgagee, filed a lawsuit against Y Dealer. X Corp. sought two primary remedies: (1) an injunction prohibiting Y Dealer from disposing of the Movables, and (2) a court order compelling Y Dealer to return the Movables to A Coop.'s factory premises (i.e., the mortgaged real property).

The Legal Journey: Immediate Acquisition and the Scope of Mortgagee's Rights

The lower courts reached different conclusions:

- The District Court: Initially dismissed X Corp.'s claims.

- The High Court: Reversed the District Court's decision and ruled in favor of X Corp. A key finding by the High Court was that Y Dealer had been negligent in believing that C (A Coop.'s representative) was the true owner of the Movables. Consequently, Y Dealer had not validly acquired ownership of the Movables through "immediate acquisition" (sokuji shutoku) – a legal principle in Japan (Civil Code Art. 192) that can allow a good-faith purchaser to obtain title to movables even from someone who is not the true owner. The High Court reasoned that merely prohibiting Y Dealer from further disposing of the Movables was insufficient to adequately protect X Corp.'s mortgage. The mortgage's value depended on the factory assets operating as an "organic integrated whole," and there was a risk that the mortgage itself could be extinguished over the Movables if a subsequent bona fide purchaser acquired them. Therefore, the High Court granted X Corp.'s demand for the return of the Movables to the factory premises.

Y Dealer appealed to the Supreme Court, arguing that while a mortgagee might have rights to prevent interference with their mortgage, the non-possessory nature of a mortgage provides no theoretical basis for demanding the physical return of separated items to the mortgaged premises or their delivery to the mortgagee.

The Supreme Court's Judgment (March 12, 1982): Upholding Return

The Supreme Court dismissed Y Dealer's appeal, thereby affirming the High Court's decision in favor of X Corp.

- Mortgage Follows Removed Movables (Under Factory Mortgage Act): The Court's central holding was: "When movables that have been made the object of a mortgage together with the land or buildings belonging to a factory pursuant to Article 2 of the Factory Mortgage Act are removed from the factory where they were installed without the consent of the mortgagee, it is reasonable to construe that the mortgagee can demand the return of the removed objective movables to the factory, their original place of installation, unless a third party has effected immediate acquisition."

- Rationale for the Right to Demand Return: The Supreme Court provided the following reasoning:

- The mortgage continues to extend its effect to such movables even after their removal from the factory, provided no third party has acquired them through immediate acquisition. The Court referenced Article 5 of the Factory Mortgage Act, which explicitly allows the mortgagee to pursue the mortgaged movables. Thus, the mortgagee can enforce the mortgage against these movables even if they are in the possession of a third party (like Y Dealer, whose claim to immediate acquisition had failed).

- To preserve the security value of the factory mortgage, merely prohibiting the further disposal of the removed movables is insufficient. The Court stated, "...it is necessary to restore the original state by returning the removed objective movables to their original place of installation."

Key Legal Concepts: Factory Mortgages and Immediate Acquisition

This judgment highlights two important Japanese legal concepts:

- Factory Mortgage Act (kōjō teitōhō): This special statute allows for the creation of a mortgage over a factory as a unified entity. This means that not only the land and buildings but also machinery, equipment, and other specified movables installed in the factory for its operational purposes can be included in a single mortgage. This enhances the factory's value as collateral by allowing it to be mortgaged (and potentially foreclosed upon) as a going concern. Article 5 of this Act grants the factory mortgagee a right to pursue mortgaged movables that have been removed, unless a third party has acquired them through immediate acquisition.

- Immediate Acquisition (sokuji shutoku): Provided by Article 192 of the Civil Code, this doctrine allows a person who, acting in good faith and without negligence, openly and peaceably begins to possess a movable, to acquire ownership of that movable immediately, even if the person who transferred it to them was not the true owner or lacked the authority to dispose of it. In this case, the High Court found Y Dealer to have been negligent in believing C's claim of ownership, thus negating the possibility of immediate acquisition. The Supreme Court proceeded on this factual basis.

The Core Issue: Mortgagee's Right to Demand Restoration of Collateral

The truly significant aspect of this ruling was its affirmation of a non-possessory mortgagee's right to demand the physical return and restoration of removed collateral, not merely an injunction against further disposal or a claim for damages. This is a powerful remedy.

Infringement of the Mortgage: For such a "real right-based claim" (bukken-teki seikyūken) to be granted, there must be an infringement of the mortgage.

- The unauthorized removal of essential machinery from a factory clearly threatens to diminish the exchange value of the factory as an integrated mortgaged unit. Legal commentary notes that infringement can occur through:

- An increased risk of the mortgagee losing their ability to pursue the movables (e.g., due to subsequent immediate acquisition by another party, or difficulty in identifying/locating them once dispersed).

- A direct loss of value if the factory's assets are broken up and sold piecemeal, rather than as an operational whole (the "organic unity" argument). The value of individual machines sold separately is often far less than their value as part of a functioning factory.

- The general academic consensus is that for a mortgagee to assert such protective rights, it is not strictly necessary to prove that the remaining collateral value has already fallen below the outstanding debt amount. An actual or threatened impairment of the security value itself is usually sufficient.

- An exception exists if the removal or disposition of mortgaged items occurs as part of the owner's ordinary and proper use or management of the factory (e.g., replacing old machinery with new). However, the actions of C in this case (claiming personal ownership and selling to a second-hand dealer) clearly did not fall under this exception.

General Civil Code Mortgages vs. Factory Mortgages on This Point

This case specifically involved a factory mortgage under the Factory Mortgage Act, which contains an express provision (Article 5) allowing the mortgage to be pursued against removed movables. A key question for legal scholars has been whether a similar right of pursuit and restoration exists for movables covered by a general Civil Code mortgage (e.g., appurtenances to a mortgaged building, as discussed in the M81 case concerning garden stones).

- The Civil Code lacks such an explicit provision for general mortgages over separated movables. Historical case law under the Civil Code was inconsistent on whether a mortgage's effect was severed upon removal of a movable component.

- Prevailing academic theories have evolved. While an older dominant view suggested that removal of a movable from the mortgaged realty would cause the mortgagee to lose the ability to assert the mortgage against third parties (due to loss of the publicity afforded by the real property mortgage registration), more recent theories argue for a stronger continuation of the mortgage's effect, often until a third party acquires the movable through immediate acquisition.

- The commentary on this 1982 judgment suggests that in a scenario like the present one—where the movables were removed without authorization by someone who was not the true owner (or at least, not acting within their rights as owner) and sold to a third party whose claim to immediate acquisition failed—the outcome (allowing the mortgagee to demand return) might be similar even under a general Civil Code mortgage, provided the movables were clearly part of the original mortgaged entity. This is because the issue isn't a conflict between two legitimate title transfers by the owner, but rather the recovery of assets wrongfully removed from the scope of a valid mortgage.

Nature of the "Return Claim" (Genjō Kaifuku Seikyūken)

Even if an infringement is established, the legal nature of the mortgagee's claim to demand the return of the removed items (a form of restoration of the original state) has been debated, given that a mortgage is typically a non-possessory security interest.

- Prior to this 1982 judgment, case law had recognized a mortgagee's right to seek an injunction to prevent the removal of mortgaged items, or to object to a third party's attempt to seize such items. This case was groundbreaking in affirming a claim for the return of items already removed.

- Academic opinion had long argued for the necessity of such a return claim to allow for the restoration of the mortgage's full value, which often depends on the unified sale of the principal property and its essential components or appurtenances.

- The precise legal characterization of this right varies among scholars: some see it as a form of claim for return of property (henkan seikyūken), others as a specific type of claim for elimination of interference (bōgai haijo seikyūken), while some consider it a unique mortgage-based real right claim. Regardless of the label, its purpose is to restore the integrity of the collateral.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's judgment of March 12, 1982, provides significant protection for holders of factory mortgages in Japan. It confirms their right to demand the physical return of essential mortgaged movables that have been wrongfully removed from the factory premises, as long as a third-party possessor has not acquired them through immediate acquisition. This right to demand restoration is deemed necessary to preserve the full security value of the factory mortgage, which often relies on the factory being treated as an integrated operational unit. While the judgment is directly based on the provisions of the Factory Mortgage Act, it has fueled discussions about the extent to which similar protective rights might be available to mortgagees under the general Civil Code, particularly in preventing the dissipation or dilution of their security through the unauthorized removal of components or appurtenances from mortgaged property. This decision underscores the judiciary's commitment to ensuring that the value of such specialized security interests is not easily undermined.