Bridging the Gap: Japan's Supreme Court on Parent-Child Visitation During Marital Separation

Date of Judgment: May 1, 2000

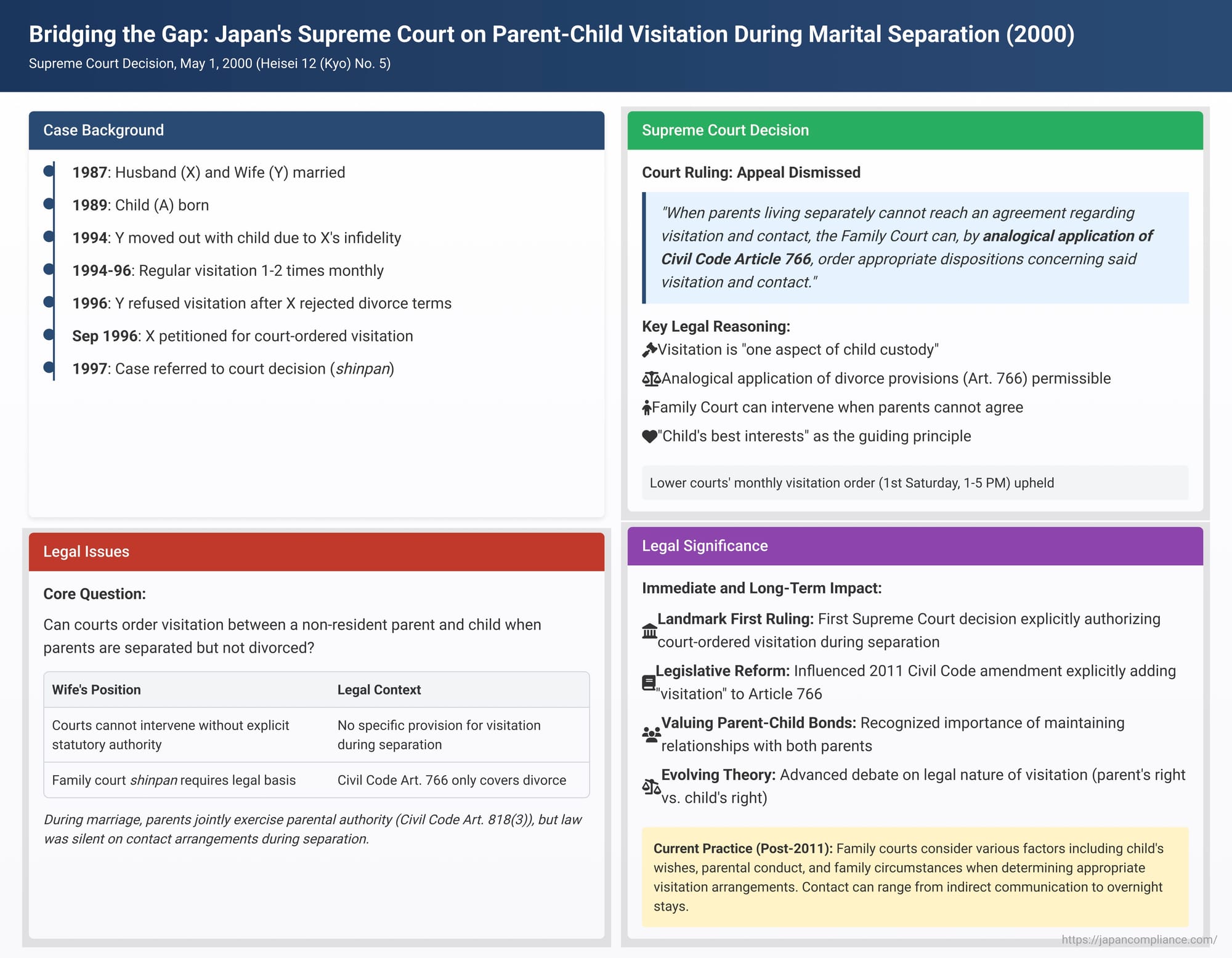

When a marriage breaks down and parents decide to live separately, one of the most pressing and often contentious issues is how the children will maintain a relationship with the non-resident parent. This contact, commonly referred to as visitation or "parent-child interaction" (面会交流 - menkai kōryū in Japanese), is widely recognized as crucial for a child's well-being. But what happens if parents, though still legally married, cannot agree on visitation arrangements during their separation? Can a court intervene to establish such contact, and if so, on what legal basis, especially when parental authority is typically shared during marriage? The Supreme Court of Japan provided a landmark clarification on this matter in a decision on May 1, 2000 (Heisei 12 (Kyo) No. 5).

The Facts: A Marriage in Crisis and a Dispute Over Child Contact

The case involved a husband, X, and his wife, Y, who had married in May 1987. Their child, A, was born in July 1989. Unfortunately, their marital relationship deteriorated, reportedly due to X's infidelity, leading Y to move out of the marital home with child A in August 1994.

Following the separation, X initiated mediation proceedings in family court seeking to be designated as A's primary custodian. Y, in turn, filed for mediation concerning divorce and solatium (damages for emotional distress). X later withdrew his custody petition, and Y's divorce mediation was ultimately unsuccessful.

Despite the ongoing conflict, a pattern of visitation between X and A was established. During the mediation period, from around December 1994, X had contact with A approximately once or twice a month. After the mediation attempts concluded, these visits continued about twice a month and proceeded without significant issues until May 1996.

The situation changed when X rejected a settlement proposal made in a separate divorce lawsuit initiated by Y. In response, Y began to refuse visitation between X and A. This led X to take measures such as waiting for A after school or visiting Y's apartment in an attempt to see his child. In September 1996, X formally petitioned the family court for mediation to establish regular visitation. However, Y remained strongly opposed, and the mediation failed. Consequently, in May 1997, the matter was referred to a formal "umpire decision" (shinpan) proceeding within the family court system – a non-contentious judicial process where a judge makes a determination.

The family court, in its shinpan, and subsequently the High Court on appeal, ordered Y to allow X to have visitation with A once a month, specifically on the first Saturday of the month from 1:00 PM to 5:00 PM.

Y, the wife, challenged this High Court decision by filing a special permission appeal to the Supreme Court. Her core legal argument was that family court shinpan proceedings, which involve state intervention in the private legal lives of individuals, are only permissible when explicitly authorized by law. She contended that there was no specific legal provision authorizing courts to order parent-child visitation arrangements for couples who were still married but living separately.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Decision: Visitation Orders Permissible During Separation via Analogical Application

The Supreme Court dismissed Y's appeal, thereby upholding the lower courts' orders for visitation. In doing so, it established a clear legal basis for family courts to intervene and determine visitation arrangements for separated but still-married parents.

The Core Principle: Analogical Application of Divorce Provisions (Civil Code Art. 766):

The Supreme Court's reasoning was as follows:

- Parental Rights and Duties During Marriage: "During the parents' marriage, the parents jointly exercise parental authority (親権 - shinken), and the person with parental authority has the right and duty to care for and educate the child (監護及び教育 - kango oyobi kyōiku) (Civil Code Art. 818(3), 820)."

- Visitation as an Aspect of Child Custody: "Even if the marital relationship has broken down and the parents are living separately, visitation and contact by the non-resident parent with the child can be said to be one aspect of child custody."

- Court Intervention When Parents Cannot Agree: "And, when parents living separately cannot reach an agreement regarding said visitation and contact, or cannot engage in consultation/agreement (協議 - kyōgi), it is appropriate to construe that the Family Court can, by analogical application of Civil Code Article 766, and pursuant to Article 9, paragraph 1, item Otsu, sub-item 4 of the Family Affairs Adjudication Law [the procedural law then in force, now covered by the Family Case Procedure Act Art. 39 & Annex 2, item 3], order appropriate dispositions concerning said visitation and contact."

At the time of this 2000 decision, Civil Code Article 766 primarily dealt with the determination of child custody, support, and other matters concerning children upon divorce. By allowing its "analogical application" to situations of pre-divorce separation, the Supreme Court provided a solid legal footing for family courts to address visitation disputes even before a marriage was formally dissolved. This was the first Supreme Court ruling to explicitly affirm this practice, which had already been developing in lower family court decisions.

The Legal Nature of "Visitation Rights": An Evolving Concept

The Supreme Court's decision focused on the procedural authority of the court to make such orders rather than delving deeply into the theoretical legal nature of visitation as a "right" of either the parent or the child. This has been a subject of considerable academic debate in Japan, especially before the explicit codification of visitation in the Civil Code.

Historically, with no express statutory provision for "visitation rights," various theories were proposed by scholars to justify court-ordered contact:

- Some viewed it as a parent's natural right, inherent in the parent-child relationship.

- Others saw it as a custody-related right, falling under the broader ambit of matters concerning the child's upbringing (as in Article 766).

- Some theories combined these, or saw it as an aspect of parental authority (even for a non-custodial parent, whose parental authority might be seen as suspended rather than extinguished).

- Increasingly, perspectives focused on visitation as a child's right, crucial for their healthy growth and development, allowing them to benefit from a relationship with both parents.

- A composite right view acknowledged both parent's and child's interests.

- Conversely, some argued that visitation was more of a procedural right (a right to petition the court for an arrangement) rather than a substantive, independently claimable right.

The Supreme Court, in an earlier 1984 case, had sidestepped the issue of whether visitation was a constitutionally protected right under Article 13 (right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness), treating it instead as a matter of statutory interpretation of custody-related provisions. The 2000 decision continued this trend, framing visitation during separation as an aspect of child custody determinable by the court.

In 2011, several years after this Supreme Court decision, Civil Code Article 766 was revised. This revision explicitly included "visitation and contact with the child" (menkai kōryū) as one of the matters to be determined by parental agreement or by the Family Court upon divorce. However, even this legislative reform did not definitively define the legal nature of visitation as primarily a parent's right or a child's right, largely because academic consensus on this point remained elusive. Since the 2011 codification, legal and academic discussions have increasingly focused on the criteria for permitting or restricting visitation and on improving the legal and social systems to support its effective implementation, with some scholars arguing for a constitutional right to visitation to bolster these implementation efforts.

Why Court Intervention During Marital Separation is Deemed Necessary

The Supreme Court's 2000 decision affirming the Family Court's authority to order visitation during pre-divorce separation is significant. It addresses the reality that failing to resolve disputes over child contact during this often volatile period can be detrimental to the child's well-being.

- Preventing Harm to Children: Leaving such disputes unaddressed can place children in the middle of parental conflict and deprive them of a relationship with one parent, which is generally considered contrary to their best interests.

- Family Court's Guardianship Role: The Family Court in Japan is often seen as having a quasi-guardianship (kōken-teki) role, particularly concerning children. Intervening to facilitate appropriate parent-child contact when parents cannot agree is consistent with this protective function.

- Modern Family Law Principles: Contemporary family law increasingly recognizes that the child's welfare can necessitate public or judicial intervention even within an ongoing marriage, especially when parental conflict impairs their ability to care for the child adequately. This ruling aligned with that evolving understanding.

By implication, this decision also reinforced the understanding that post-divorce visitation arrangements (involving a non-custodial parent) are properly matters for family court shinpan proceedings.

Determining Visitation Arrangements: The "Child's Best Interests" as the Paramount Standard

The guiding principle in all judicial decisions concerning parent-child visitation in Japan, whether during separation or after divorce, is the "best interests of the child" (子の利益 - ko no rieki). This standard was explicitly incorporated into the revised Civil Code Article 766 in 2011. Current court practice generally operates on the premise that appropriate and regular interaction with both parents is beneficial for a child's sound emotional and psychological development, unless specific circumstances suggest that such contact would be harmful.

When determining the specifics of visitation, courts consider various factors:

- The Child's Wishes: The Family Case Procedure Act (Article 65) mandates that courts endeavor to ascertain the child's intentions in proceedings that will affect them. Children aged 15 and above are typically directly heard by the court. For younger children, family court investigators (家裁調査官 - kasai chōsakan) will often assess their views and feelings. However, a child's expressed desire, especially a refusal of visitation, is not always determinative. Courts will carefully examine the reasons behind a child's reluctance, considering whether it stems from undue influence by one parent or from genuine anxieties related to past experiences.

- Conduct of the Non-Resident Parent: A history of child abuse or domestic violence by the parent seeking visitation is a very strong factor for denying or severely restricting contact. Even spousal conflict or violence between the parents, if it has negatively impacted the child or creates a harmful environment for visitation, will be taken into account.

- Custodial Parent's Remarriage and Stepfamily Formation: While earlier court decisions sometimes limited visitation if the custodial parent had remarried and formed a new stepfamily (to prioritize the stability of the new family unit), current practice generally does not view remarriage as an automatic reason to deny or curtail visitation with the non-resident biological parent. The focus remains on the child's overall welfare, which often includes maintaining ties with both biological parents.

- Forms of Visitation: Court-ordered visitation can take many forms, tailored to the specific circumstances. It can range from indirect contact, such as exchanging letters, photographs, emails, or having phone/video calls, to allowing the non-resident parent to attend school events. More direct forms include short daytime visits, progressing to longer visits, and in some cases, overnight stays or even periods of shared care. The frequency, duration, and conditions of visitation depend on factors like the child's age and developmental stage, the history of the parent-child relationship, the level of parental conflict, and geographical distance. In high-conflict situations, visitation may be supervised or facilitated by third-party organizations.

It's also noteworthy that a parent's attitude towards visitation can influence broader custody decisions. Courts often view a parent's willingness to support and facilitate the child's relationship with the other parent (sometimes referred to as the "friendly parent" principle) as a positive indicator of their suitability as the primary custodian, as this approach is generally seen as serving the child's best interests by allowing them to maintain meaningful connections with both parents.

Conclusion: Affirming Judicial Support for Parent-Child Bonds During Separation

The Supreme Court of Japan's decision on May 1, 2000, was a vital step in clarifying the legal framework for parent-child visitation when married parents are living apart but not yet divorced. By endorsing the analogical application of divorce-related custody provisions, the Court empowered Family Courts to make necessary orders to ensure that children can maintain relationships with both parents, provided it serves their best interests. This ruling recognized the importance of continued parent-child bonds even amidst marital strife and paved the way for the later explicit inclusion of visitation rights in the Civil Code for divorcing couples. It underscores a legal commitment to prioritizing the child's welfare and fostering ongoing parental involvement where feasible, adapting legal principles to meet the evolving needs of families in transition.