Bridging the Atlantic Again? Understanding the EU-US Data Privacy Framework

TL;DR

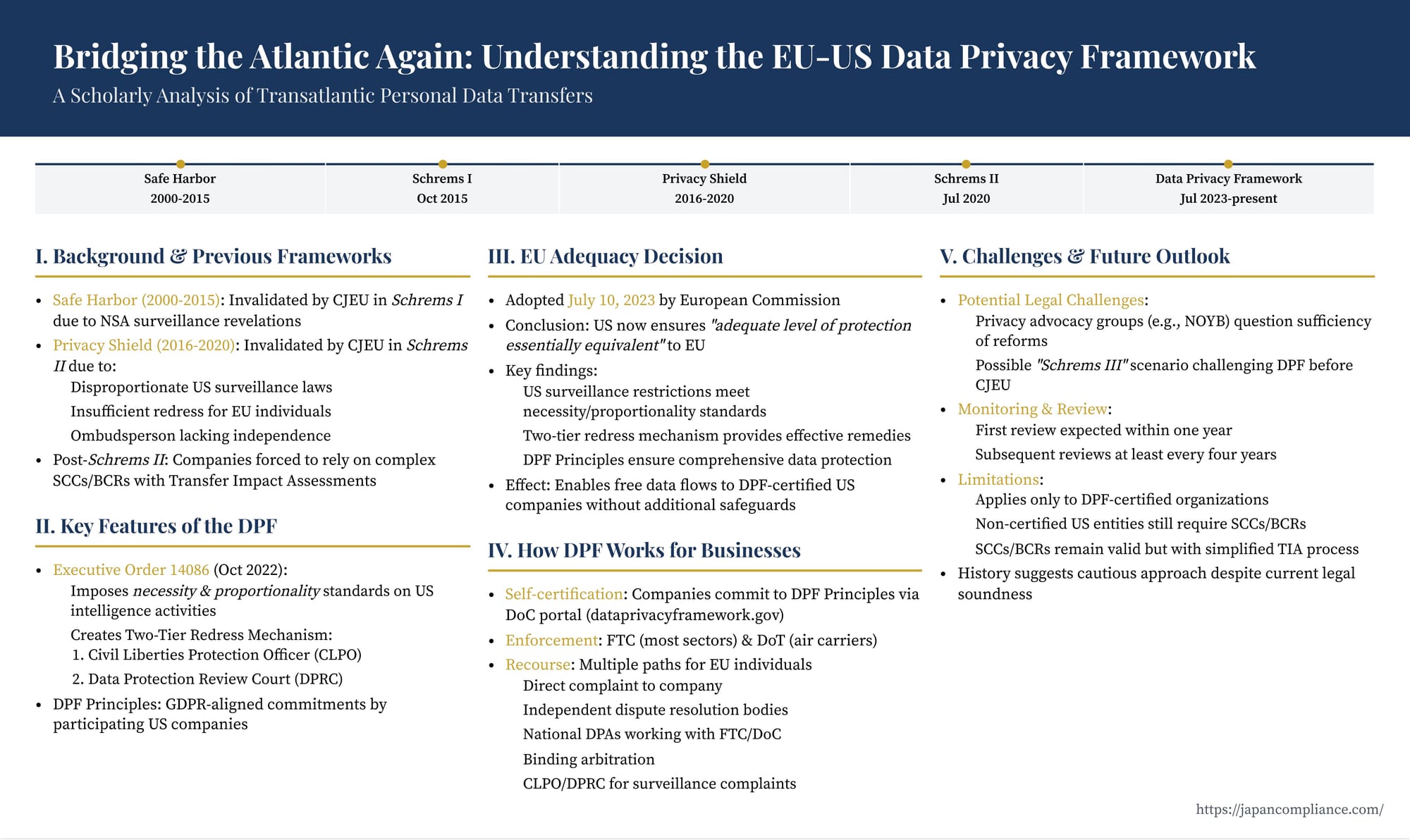

- After Schrems II, the new EU-US Data Privacy Framework (DPF) won an adequacy decision on 10 July 2023 thanks to U.S. Executive Order 14086 and a two-tier redress system.

- EU data can flow to DPF-certified U.S. companies without SCCs/BCRs, but transfers to non-certified entities still need alternative safeguards.

- Legal challenges (“Schrems III”) remain possible; businesses should monitor reviews and keep SCC/BCR options ready.

Table of Contents

- The Challenge: GDPR Adequacy vs. US Surveillance

- The Third Attempt: The EU-US Data Privacy Framework (DPF)

- The EU Adequacy Decision for the DPF (July 10, 2023)

- How Does the DPF Work for Businesses?

- Challenges and Future Outlook

- Conclusion

The free flow of personal data between the European Union (EU) and the United States is fundamental to the transatlantic digital economy. However, establishing a stable legal mechanism for these transfers under the EU's stringent General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) has proven remarkably challenging. Two previous frameworks, Safe Harbor and Privacy Shield, were invalidated by the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) due to concerns about US government surveillance practices. In July 2023, a third attempt, the EU-US Data Privacy Framework (DPF), received an adequacy decision from the European Commission. This post explores the DPF's background, key features, and implications for businesses reliant on EU-US data flows.

The Challenge: GDPR Adequacy vs. US Surveillance

The core conflict stems from differing legal traditions. The GDPR treats personal data protection as a fundamental right and imposes strict conditions on transferring data outside the EU/EEA. Under GDPR Article 45, transfers can flow freely only to countries deemed by the European Commission to provide an "adequate" level of protection, essentially equivalent to that within the EU.

The US, lacking a comprehensive federal data protection law comparable to GDPR, has struggled to meet this adequacy standard. The primary obstacle, highlighted in landmark CJEU rulings, has been the scope of US government access to data (particularly electronic communications) for national security purposes and the perceived lack of effective legal redress for EU individuals whose data might be accessed by US intelligence agencies.

- Safe Harbor (2000-2015): This initial framework allowed US companies to self-certify compliance with a set of privacy principles. However, following Edward Snowden's revelations about NSA surveillance programs (like PRISM), the CJEU invalidated the Safe Harbor adequacy decision in Schrems I (Case C-362/14, October 6, 2015). The Court found that US law enabling broad government access to transferred data, without adequate judicial oversight or redress for EU individuals, undermined the "adequate protection" required by EU law.

- Privacy Shield (2016-2020): Developed to replace Safe Harbor, Privacy Shield included stronger privacy principles and introduced an Ombudsperson mechanism within the US State Department intended to handle EU complaints regarding surveillance. Nevertheless, the CJEU also invalidated the Privacy Shield adequacy decision in Schrems II (Case C-311/18, July 16, 2020). The Court reaffirmed that US surveillance laws (notably FISA Section 702 and Executive Order 12333) were not limited to what was strictly necessary and proportionate under EU fundamental rights standards. It also found the Ombudsperson mechanism insufficient, lacking the necessary independence and power to issue binding decisions against intelligence agencies, thus failing to provide effective redress.

The Schrems II ruling significantly disrupted transatlantic data flows, forcing many businesses to rely on alternative transfer mechanisms like Standard Contractual Clauses (SCCs) or Binding Corporate Rules (BCRs). However, the CJEU also stated that even when using SCCs/BCRs for US transfers, companies had to conduct case-by-case assessments (Transfer Impact Assessments or TIAs) and potentially implement "additional safeguards" to address the identified gaps in US law regarding surveillance – a complex and often uncertain process.

The Third Attempt: The EU-US Data Privacy Framework (DPF)

Negotiations between the EU and US intensified after Schrems II, culminating in a political agreement in March 2022 and key reforms on the US side, primarily through Executive Order (EO) 14086, "Enhancing Safeguards for United States Signals Intelligence Activities," signed in October 2022. This EO introduced crucial changes aimed directly at addressing the CJEU's concerns:

- Binding Safeguards on US Intelligence Activities:

- Necessity and Proportionality: EO 14086 establishes that US signals intelligence activities must be conducted only when necessary to advance legitimate, validated national security objectives and only in a manner proportionate to those objectives. It requires intelligence agencies to consider privacy and civil liberties in their activities. These standards are intended to apply to data collected from any country, but the specific redress mechanisms are for designated states.

- New Two-Tier Redress Mechanism: EO 14086 created a new system for individuals in designated "qualifying states" (which includes the EU/EEA countries) whose personal data was transferred from the EU/EEA to the US, allowing them to seek redress if they believe their data was unlawfully collected or handled by US signals intelligence activities:

- Tier 1: Civil Liberties Protection Officer (CLPO): Individuals can submit complaints to the CLPO within the Office of the Director of National Intelligence (ODNI). The CLPO conducts an independent investigation and can issue binding decisions, including remedial measures, against intelligence agencies.

- Tier 2: Data Protection Review Court (DPRC): Individuals dissatisfied with the CLPO's decision (or if the CLPO doesn't confirm compliance) can appeal to the newly established DPRC. Located within the Department of Justice but composed of independent judges appointed from outside the US government, the DPRC provides independent judicial review. Its decisions are binding on intelligence agencies and can include remedies like data deletion. A "special advocate" system is also established to represent the complainant's interests in DPRC proceedings, including access to relevant classified information.

Alongside these government-level commitments, the DPF Principles were developed by the US Department of Commerce (DoC). US organizations voluntarily participate in the DPF by self-certifying their adherence to these Principles, which largely align with GDPR concepts such as notice, choice (consent), accountability for onward transfer, security, data integrity and purpose limitation, access rights, and recourse/enforcement.

The EU Adequacy Decision for the DPF (July 10, 2023)

Based on the safeguards introduced by EO 14086 and the commitments under the DPF Principles, the European Commission formally adopted an adequacy decision for the EU-US Data Privacy Framework on July 10, 2023.

The Commission concluded that the US now ensures an adequate level of protection – essentially equivalent to that of the EU – for personal data transferred under the DPF. Specifically, it found that the new rules on government access meet the GDPR's requirements of necessity and proportionality, and that the two-tier redress mechanism provides effective remedies for EU individuals, addressing the deficiencies identified in Schrems II.

Effect: This adequacy decision allows personal data to flow freely and safely from controllers and processors in the EU/EEA to US companies certified under the DPF, without the need for additional data protection safeguards like SCCs or BCRs.

How Does the DPF Work for Businesses?

- Self-Certification: US companies wishing to receive personal data from the EU/EEA under the DPF must self-certify their compliance with the DPF Principles to the US Department of Commerce through an online portal (dataprivacyframework.gov). This involves making public commitments to adhere to the Principles.

- Public List: The DoC maintains and publishes a list of DPF-certified organizations. EU/EEA data exporters can verify a US recipient's participation on this list.

- Compliance & Enforcement: Certified companies must implement policies and procedures to meet the DPF Principles. Compliance is primarily enforced by the US Federal Trade Commission (FTC) for most sectors, using its authority under Section 5 of the FTC Act against unfair or deceptive acts or practices. The Department of Transportation (DoT) has enforcement authority for certain air carriers and ticket agents. Making false claims of participation or failing to adhere to the Principles can lead to FTC/DoT enforcement actions.

- Recourse for Individuals: The DPF provides several avenues for individuals to raise concerns: lodging complaints directly with the certified company, utilizing designated independent dispute resolution bodies (at no cost to the individual), referring complaints to their national DPA (who will work with the DoC and FTC), or pursuing binding arbitration under certain conditions. For complaints specifically related to government surveillance access, the new two-tier CLPO/DPRC mechanism applies.

Challenges and Future Outlook

While the DPF provides a renewed basis for transatlantic data flows, uncertainties remain:

- Potential Legal Challenges: Privacy advocacy groups, notably Max Schrems' NOYB, have expressed skepticism about whether EO 14086 sufficiently limits US surveillance or if the DPRC qualifies as a fully independent judicial remedy under EU law. Further legal challenges to the DPF adequacy decision before the CJEU are considered likely, potentially leading to a "Schrems III" scenario.

- Monitoring and Review: The European Commission will continuously monitor developments in the US legal framework and conduct periodic reviews of the adequacy decision (the first review expected within a year of entry into force, and then at least every four years). The functioning of the new redress mechanism will be under close scrutiny.

- Scope Limitations: The adequacy decision applies only to transfers made to US organizations certified under the DPF. Transfers to non-certified US entities still require other mechanisms like SCCs or BCRs.

- Relationship with SCCs/BCRs: While the DPF simplifies transfers to certified entities, SCCs and BCRs remain valid transfer tools. The DPF adequacy finding significantly simplifies the Transfer Impact Assessment (TIA) process required when using SCCs/BCRs for transfers to the US, as the assessment of US surveillance law is largely addressed by the adequacy finding itself, though companies still need to assess the specific circumstances of their transfer.

Conclusion

The EU-US Data Privacy Framework marks a significant development in the ongoing effort to facilitate vital transatlantic data flows while respecting fundamental rights. By incorporating substantial reforms on the US side aimed at addressing the CJEU's concerns from the Schrems decisions, the DPF currently offers businesses a more streamlined and legally sound pathway for transferring personal data from the EU/EEA to certified US partners compared to the complexities of SCCs post-Schrems II. However, the history of previous frameworks and the potential for renewed legal challenges mean that businesses should remain vigilant, closely monitor developments, and ensure robust compliance practices, whether participating in the DPF or utilizing alternative GDPR transfer mechanisms.