Breaking Down Secrecy: Japan's Supreme Court on Disclosing Parts of Personal Information in Public Documents

Judgment Date: April 17, 2007

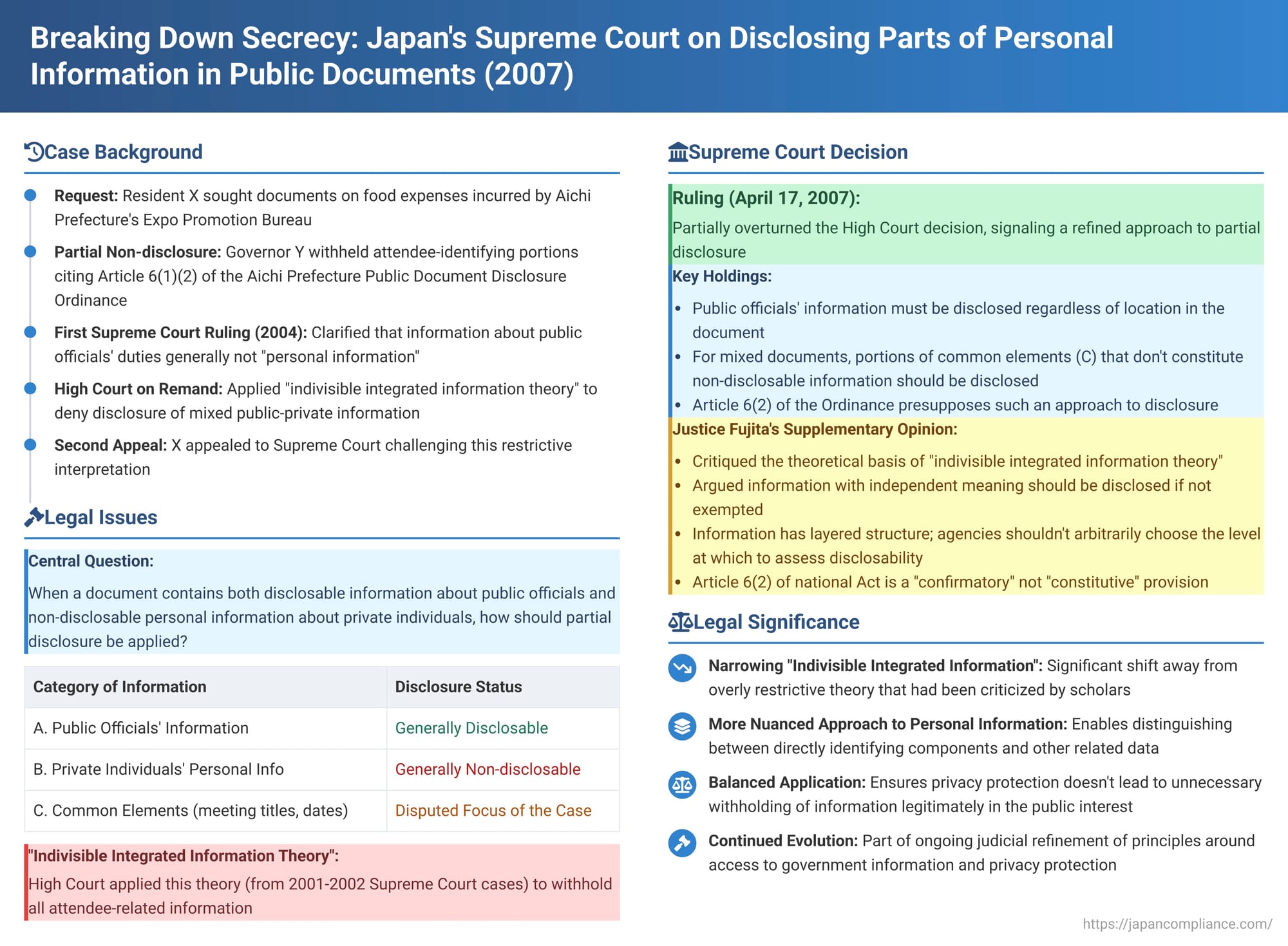

The principle of public access to government-held documents is a cornerstone of transparent governance, yet it frequently encounters the need to protect personal privacy. When a single public document contains both information that should be disclosed and personal information that warrants protection, the question arises: how much of the document can, or must, be released? A Japanese Supreme Court decision from April 17, 2007 (Heisei 18 (Gyo-Hi) No. 50), delved into this complex issue, particularly clarifying the "unit" of non-disclosable information and refining the approach to partial disclosure under a local information disclosure ordinance[cite: 1]. This case is pivotal for understanding how Japanese law balances transparency with the safeguarding of personal data within public records.

The Aichi Expo Fund Saga: A Quest for Meeting Details

The case was initiated by X, a resident of Aichi Prefecture, who requested access to public documents under the Aichi Prefecture Public Document Disclosure Ordinance (prior to its complete revision in 2000, hereinafter "the Ordinance")[cite: 1]. The request targeted records related to food expenses incurred by the Aichi Prefectural Commerce and Industry Department's Expo Promotion Bureau for various meetings, consultations, and discussions ("the respective meetings")[cite: 1]. These documents included budget execution forms, payment records, and invoices ("the subject documents"), some of which contained information that could identify attendees of these meetings ("attendee-identifying portions")[cite: 1].

The Governor of Aichi Prefecture, Y (the defendant), responded with a decision of partial non-disclosure[cite: 1]. The primary reason for withholding certain parts was that they contained "personal information" deemed non-disclosable under Article 6, paragraph 1, item 2 of the Ordinance[cite: 1]. This provision generally allows for the non-disclosure of information concerning individuals (excluding information about individuals engaged in business, regarding that business) by which a specific individual can be identified[cite: 1].

The case had a complex journey through the court system. After initial proceedings in the Nagoya District Court and the Nagoya High Court, it reached the Supreme Court for the first time[cite: 1]. In this first Supreme Court appeal (November 26, 2004), the Court clarified an important principle: information concerning the performance of duties by public officials, unless it includes purely private matters of the official, generally does not constitute non-disclosable "personal information" under the Ordinance's Article 6(1)(2)[cite: 1]. Because the status of the meeting attendees (whether they were public officials or private individuals) had not been definitively established by the lower courts, the Supreme Court remanded the case to the Nagoya High Court for further fact-finding[cite: 1].

The Remand Appeal Court (Nagoya High Court) then determined the status of the attendees[cite: 1]. It proceeded to consider the possibility of partial disclosure under Article 6, paragraph 2 of the Ordinance[cite: 1]. This provision, similar to Article 6, paragraph 1 of Japan's national Act on Access to Information Held by Administrative Organs, generally mandates disclosure of portions of a document that do not contain non-disclosable information, provided these portions can be easily separated without harming the purpose of the disclosure request[cite: 1].

However, the Remand Appeal Court adopted a restrictive stance for documents that contained a mixture of:

(A) Information about public officials' attendance (generally disclosable),

(B) Personal information of non-public officials (generally non-disclosable), and

(C) Information common to both (e.g., meeting titles, dates).

Citing a 2002 Supreme Court precedent (Heisei 14 Saikōsai Hanketsu, February 28, 2002), the Remand Appeal Court invoked the "indivisible integrated information theory" (dokuritsu ittaiteki jōhō ron)[cite: 1]. It held that the Ordinance's partial disclosure provision (Art. 6(2)) could not be interpreted to compel the implementing agency to further subdivide what it considered an "indivisible integrated piece of information" (in this context, the non-disclosable personal information of non-public attendees) simply to disclose remaining parts that, on their own, might not be non-disclosable[cite: 1]. Based on this theory, the Remand Appeal Court concluded that all attendee-related information in such mixed documents should be withheld, and it denied partial disclosure of the public officials' information when intertwined with private individuals' information in this manner[cite: 1]. X appealed this decision, leading to the current 2007 Supreme Court judgment[cite: 1].

The Supreme Court's 2007 Decision: A Shift Towards Greater Disclosure

The Supreme Court, Third Petty Bench, in its April 17, 2007, judgment, partially overturned the Remand Appeal Court's decision, signaling a significant refinement in the approach to partial disclosure, particularly moving away from an overly broad application of the "indivisible integrated information theory"[cite: 1].

Public Officials' Information Must Be Disclosed

The Court first reiterated and reinforced the principle from its earlier remand judgment: When the subject documents contain information about public officials attending meetings, and this information itself does not qualify as non-disclosable personal information (category [A] above), it must be disclosed in its entirety[cite: 1]. This applies regardless of where this information is located within the document—whether in sections describing the meeting's title, purpose, content, or any other part[cite: 1].

Disclosure of Common Elements in Mixed Information Documents

The more groundbreaking part of the decision concerned documents containing a mix of disclosable information about public officials [A] and non-disclosable personal information of private individuals [B], along with common descriptive elements [C] (such as meeting titles or dates)[cite: 1]. The Supreme Court ruled that even in such mixed documents, the portions of these common elements [C] that do not themselves constitute non-disclosable information should be disclosed as information pertaining to the public officials' attendance[cite: 1]. Specifically, descriptive parts that serve to identify the attending public officials (like their names, affiliations, or job titles) should be disclosed[cite: 1].

Crucially, the Court stated that Article 6, paragraph 2 of the Ordinance (the general partial disclosure provision) should be interpreted as presupposing such an approach to disclosure[cite: 1]. It referenced a 2003 Supreme Court precedent (November 11, 2003, Third Petty Bench) in support of this interpretation[cite: 1]. This effectively meant that the presence of non-disclosable personal information of private citizens within common descriptive parts should not automatically render those entire descriptive parts non-disclosable if they also contain information about public officials that is otherwise subject to disclosure[cite: 1].

Deconstructing the "Indivisible Integrated Information Theory": The Fujita Supplementary Opinion

To fully grasp the theoretical underpinnings of this 2007 decision, the supplementary opinion by Justice Hisanori Fujita is indispensable[cite: 1]. Justice Fujita, while concurring with the majority's conclusion, provided a detailed critique of the "indivisible integrated information theory" that the Remand Appeal Court had relied upon, a theory that had its roots in earlier Supreme Court decisions from 2001 and 2002[cite: 1].

Justice Fujita argued the following points:

- Lack of Theoretical Basis: He found no sound theoretical basis for the interpretation that information, which in itself is not non-disclosable, should be withheld merely because it forms part of a "larger, more comprehensive, integrated piece of information"[cite: 1]. He asserted that if a piece of information (like the name of an attending public official) is meaningful on its own and not subject to any non-disclosure grounds, it should be disclosed[cite: 1]. The argument that it is merely a "part" of a larger, non-disclosable whole (due to the presence of private individuals' information) is not a valid reason for withholding the disclosable part[cite: 1].

- Layered Structure of Information vs. Agency Discretion: Information recorded in a document inherently possesses a layered structure, from the smallest units of data to more comprehensive collections of information[cite: 1]. For instance, information about the Supreme Court includes information about its Third Petty Bench, which in turn includes information about Justice Fujita, which further includes information about cases he was involved in[cite: 1]. Justice Fujita contended that the current information disclosure legal framework in Japan does not grant administrative agencies the authority to arbitrarily decide at which "level" or "phase" of this layered structure they will assess disclosability[cite: 1].

- National Act's Article 6(2) as a "Confirmatory Provision": The Remand Appeal Court's reasoning (and that of the 2002 Supreme Court precedent it cited) was partly based on the absence in the Aichi Ordinance of a provision exactly like Article 6, paragraph 2 of the national Information Disclosure Act[cite: 1]. This national provision specifically addresses "personal information" (defined in Art. 5(1) of the national Act) and allows for the disclosure of such information after removing the parts that enable identification of a specific individual, provided this removal does not harm the individual's rights and interests and the remaining part is "deemed" not to be personal information[cite: 1]. Justice Fujita argued that Article 6(2) of the national Act is not a "constitutive" provision (i.e., one that creates a new obligation to make partial disclosure where none existed). Rather, it is a "confirmatory provision" (kakuninteki kitei)[cite: 1]. He explained that it was included as a special measure because "personal information" as an exemption category (Art. 5(1) of the national Act) is very broad in its wording compared to other exemptions (Art. 5(2)-(6)), which are typically qualified by phrases like "likelihood of harm"[cite: 1]. Article 6(2) was therefore intended to ensure that the general principle of partial disclosure (already established in Article 6, paragraph 1 of the national Act) is reliably applied even to this broad category of personal information[cite: 1]. Misinterpreting the purpose of this provision, he argued, leads to erroneous conclusions about the scope of partial disclosure[cite: 1].

- Reconciling with Past Precedents: While Justice Fujita suggested that the 2001 and 2002 Supreme Court precedents (which heavily influenced the "indivisible integrated information theory") were, in his view, based on a misinterpretation of the law and should ideally be overturned, he also offered a way to reconcile the conclusion of the present 2007 judgment with them[cite: 1]. He noted that the general partial disclosure rule (e.g., Art. 6(1) proviso of the national Act) does not require disclosure of remnants that are not, in themselves, meaningful information[cite: 1]. If the "integrated information" referred to in the 2001 and 2002 precedents is narrowly construed to mean only the minimum unit of meaningful information, then disclosing the names of attending public officials (as ordered in the 2007 judgment) would not necessarily conflict with the outcomes of those earlier cases[cite: 1]. He posited that this narrower understanding is what underlies the 2007 judgment and a 2003 Supreme Court decision on which the majority relied[cite: 1].

The Broader Legal Context and Commentary

The core legal problem addressed by this line of cases is how to apply partial disclosure principles when a document contains non-disclosable personal information mixed with other, potentially disclosable, information, particularly when the governing local ordinance only has a general partial disclosure rule (like Aichi's Art. 6(2)) and lacks a more specific "deeming" provision for personal information akin to Article 6, paragraph 2 of the national Information Disclosure Act[cite: 1].

The 2001 and 2002 Supreme Court judgments, with their "indivisible integrated information theory," had been widely criticized by legal scholars and practitioners[cite: 1]. The main criticisms were that:

- The scope of "indivisible integrated information" was interpreted too broadly, leading to excessive non-disclosure[cite: 1].

- This interpretation seemed to deviate from the original legislative intent of many local ordinances, the general spirit of information disclosure (which aims for maximum possible openness), and the legislative history behind Article 6, paragraph 2 of the national Act[cite: 1].

- Article 6, paragraph 2 of the national Act should be understood as a confirmatory provision, clarifying the application of general partial disclosure rules to personal information, rather than as a unique, constitutive provision without which such partial disclosure of personal information is impossible[cite: 1].

The 2007 Supreme Court judgment is therefore seen by many commentators as a landmark decision that signaled a crucial departure from, or at least a significant narrowing of, the strict "indivisible integrated information theory"[cite: 1]. It did not explicitly overturn the 2001 and 2002 precedents, but Justice Fujita's opinion provided a strong theoretical basis for a more disclosure-friendly approach[cite: 1].

Legal commentary suggests that the logic of the 2007 ruling allows for a more nuanced understanding of "personal information" in the context of partial disclosure[cite: 1]. Only the "identifying part" (e.g., a name) might be considered a fact-based, automatically non-disclosable item[cite: 1]. The "other parts" (e.g., records of an individual's actions or surrounding contextual information) could then be treated as qualitatively non-disclosable only if, after removing the directly identifying part, their disclosure still poses a "likelihood of harm" to the individual's rights and interests[cite: 1]. If this interpretation holds, then these "other parts" would be handled similarly to other categories of non-disclosable information (like trade secrets or national security information), where the "likelihood of harm" is the key determinant[cite: 1]. This would mean that if a document contains "other parts" of personal information some of which pose a risk of harm and some of which do not, the latter should be disclosed[cite: 1]. Such an approach, it is argued, would render complex conceptual gymnastics around "indivisible integrated information" or "layered structures of information" largely unnecessary[cite: 1]. The 2007 judgment, by effectively shrinking the application of the "indivisible integrated information" concept, aimed to correct potential misunderstandings and overly restrictive interpretations that had arisen from the 2001 precedent[cite: 1].

Despite the 2007 Supreme Court decision, its influence on subsequent lower court rulings has not been entirely uniform. Some later lower court decisions continued to cite the 2001 precedent and maintain the "indivisible integrated information theory," or to interpret provisions like Article 6(2) of the national Act as constitutive rather than confirmatory[cite: 1]. This judicial tendency contrasts somewhat with the approach of the Information Disclosure and Personal Information Protection Review Board (an oversight body), which, since around 2002, has generally rejected arguments for non-disclosure based on the indivisible information theory[cite: 1]. However, a more recent Supreme Court judgment in 2018 (concerning Cabinet Secretariat discretionary funds) notably made its decision without referring to the "indivisible integrated information theory," even though it had been discussed in the lower courts of that case, perhaps signaling a continued, albeit gradual, judicial shift away from the restrictive theory[cite: 1].

Implications for Information Disclosure Practice

The 2007 Supreme Court decision has significant practical implications for how administrative agencies and courts approach the partial disclosure of documents containing personal information. It encourages a more granular assessment of information, moving away from withholding large blocks of data simply because they contain some non-disclosable personal elements. The judgment, particularly when read with Justice Fujita's opinion, supports the idea of carefully distinguishing between the directly identifying components of personal information and other related data. For these "other" data, the focus should shift to whether their disclosure, even after the removal of names or other direct identifiers, would still pose a genuine likelihood of harm to individual rights and interests. This promotes a more balanced application of disclosure laws, ensuring that the protection of personal privacy does not inadvertently lead to the unnecessary withholding of other information that is legitimately in the public interest to disclose.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's April 17, 2007, judgment represents a crucial development in Japanese information disclosure law, particularly concerning the complex issue of partially disclosing documents that contain personal information. By reining in the potentially over-restrictive "indivisible integrated information theory" and advocating for a more nuanced approach that focuses on the actual risk of harm after severing identifiable elements, the Court took a significant step towards ensuring that public access to information is maximized wherever possible. This decision underscores the ongoing judicial effort to refine legal principles so that the fundamental right to access government-held information is robustly protected, while legitimate privacy concerns continue to be appropriately addressed. It emphasizes that non-disclosable personal data should not act as an impermeable shield hiding other information that the public has a right to see.