Born of a Woman: How a 1962 Japanese Supreme Court Case Cemented the "Birth Establishes Motherhood" Principle

Judgment Date: April 27, 1962 (Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench)

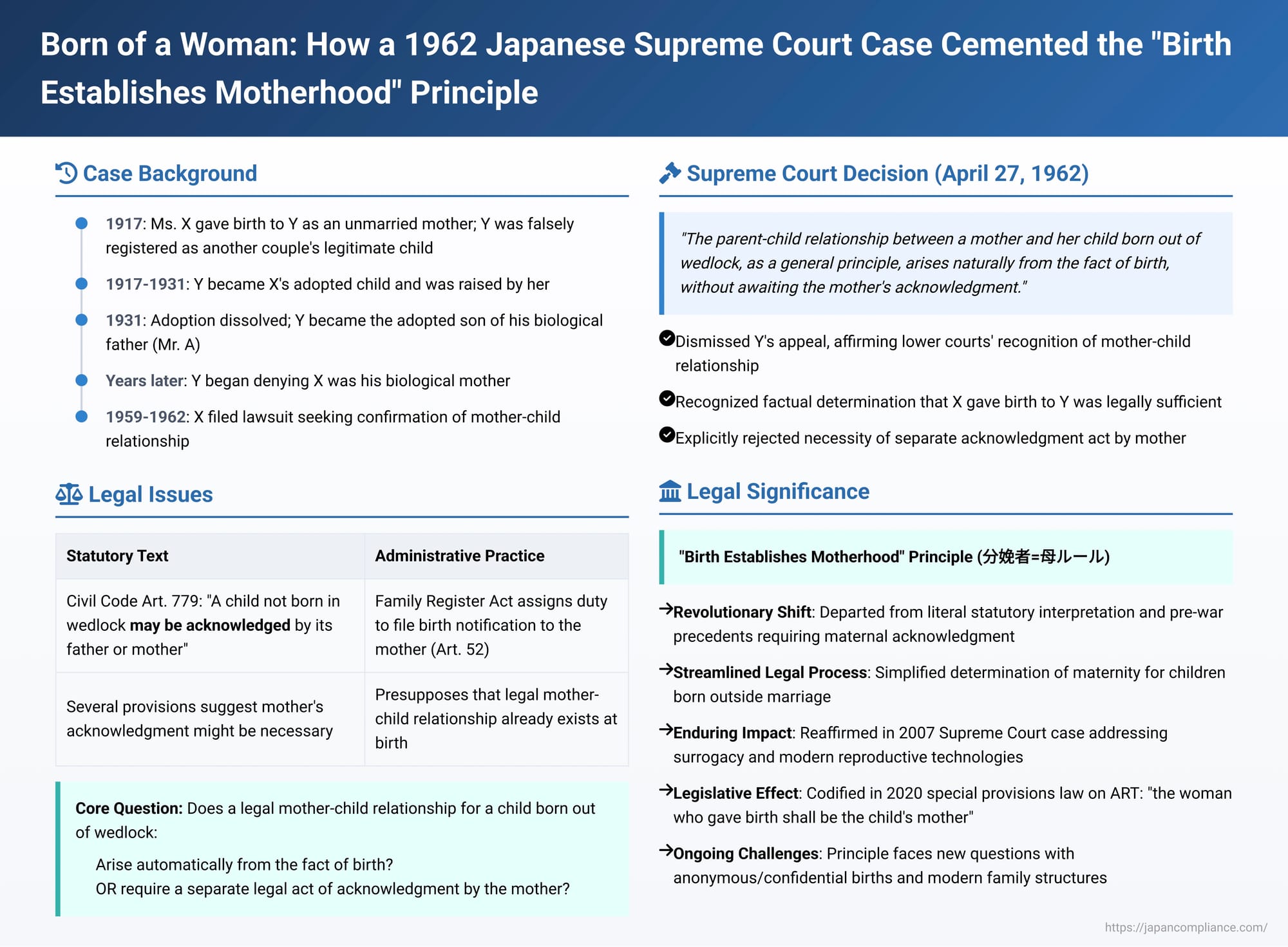

In a landmark decision that continues to resonate through Japanese family law, the Supreme Court of Japan in 1962 fundamentally clarified how the legal relationship between a mother and her child born outside of marriage is established. The ruling, issued in a "Parent-child Relationship Existence Confirmation Case" (親子関係存在確認請求事件, Oyako Kankei Sonzai Kakunin Seikyū Jiken), declared that, as a general principle, maternity arises automatically from the fact of birth, without requiring a separate legal act of acknowledgment by the mother. This was a pivotal moment, streamlining the understanding of maternal ties and setting a precedent that would later inform discussions around modern assisted reproductive technologies.

A Tangled Family History: The Path to Court

The case presented a complex web of personal relationships and formal registrations. Ms. X, the plaintiff (and later appellee), had been the mistress of a Mr. A. In July 1917 (Taisho 6), Ms. X gave birth to a son, Y, the defendant (and later appellant). [cite: 1] Because Y was born out of wedlock, he was not entered into the family register (koseki) of either Mr. A's household or Ms. X's household. [cite: 1] Instead, a birth notification was filed falsely registering Y as the legitimate child of a different couple, Mr. and Mrs. B. [cite: 1]

Shortly thereafter, in August 1917, Y became the legally adopted child of Ms. X and was raised by her until he reached adulthood. [cite: 1] In 1931 (Showa 6), a significant shift occurred: to enable Y to succeed to Mr. A's family business, the adoption between Y and Ms. X was formally dissolved, and Y then became the adopted son of Mr. A. [cite: 1] Many years later, Y began to deny that Ms. X was his biological mother. [cite: 1] This denial prompted Ms. X to file a lawsuit seeking legal confirmation of the existence of a mother-child relationship between herself and Y. [cite: 1]

The court of first instance (Tokyo District Court, January 30, 1959) found in favor of Ms. X. It recognized the mother-child relationship based on its factual finding that Ms. X had indeed given birth to Y, without making a specific determination as to whether Ms. X had formally "acknowledged" Y in a separate legal sense. [cite: 1] This decision was upheld by the appellate court (Tokyo High Court, July 25, 1960), which adopted the reasoning of the first instance court. [cite: 1] Mr. Y subsequently appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Definitive Statement

The Supreme Court dismissed Mr. Y's appeal, affirming the lower courts' decisions. [cite: 1] The Court found that the factual determination by the lower courts—that Ms. X had given birth to Y—was adequately supported by the evidence presented and free of any legal error. [cite: 1]

However, the most impactful part of the judgment came in an addendum (附言, fugen), a supplementary comment by the Court:

"Furthermore, it is appropriate to understand that the parent-child relationship between a mother and her child born out of wedlock, as a general principle, arises naturally from the fact of birth, without awaiting the mother's acknowledgment. Therefore, the original judgment, which recognized the existence of a parent-child relationship solely by certifying the fact that X gave birth to Y, without determining the fact of acknowledgment by X, is proper." [cite: 1]

This short passage was revolutionary. It established, for the first time at the Supreme Court level, that the biological act of giving birth is, in itself, generally sufficient to create the legal mother-child bond for children born outside of marriage. [cite: 1]

The Significance: "Birth Establishes Motherhood"

The 1962 ruling had profound implications, particularly when contrasted with the then-existing statutory language and historical legal thought concerning maternal acknowledgment.

A Departure from Literal Statutory Interpretation:

Japan's Civil Code, in Article 779, states: "A child not born in wedlock may be acknowledged by its father or mother." [cite: 1] Several other provisions related to acknowledgment (Articles 780, 783(2), 785, 787 proviso, and 789(2)) similarly refer to or presuppose the possibility of a mother's acknowledgment. [cite: 1] Taken literally, these articles suggest that an act of acknowledgment by the mother might be a necessary step to formalize the legal relationship with her child born out of wedlock. The Supreme Court's 1962 decision, however, indicated that for mothers, the act of birth itself generally fulfills this role, rendering a separate acknowledgment largely unnecessary. [cite: 1]

Historical Roots of "Mother's Acknowledgment":

The concept of a mother needing to acknowledge her child born out of wedlock was not an indigenous Japanese legal tradition. It was introduced during the drafting of the Meiji Civil Code (which came into effect in 1898), drawing inspiration from French law. [cite: 1] The drafters of the Meiji Civil Code included Article 827, which stated, "An illegitimate child may be acknowledged by its father or mother." [cite: 1]

Their reasoning for requiring maternal acknowledgment included:

- Uncertainty in Specific Cases: While childbirth usually makes maternity clear, situations like abandoned children (kiji, 棄児) or children born under false birth registrations could create ambiguity about the true mother. Requiring acknowledgment was seen as a way to clarify these cases. [cite: 1]

- Preventing Child Abandonment: There was a concern that if a legal maternal relationship arose automatically from birth (a concept termed 当然発生主義, tōzen hassei shugi, or "automatic arising principle"), it might paradoxically lead to an increase in child abandonment by mothers wishing to avoid this automatic legal tie. The "acknowledgment principle" (認知主義, ninchi shugi), where the relationship is formed by a deliberate act of acknowledgment, was thought to be a better approach to mitigate this risk. [cite: 1]

Despite facing considerable criticism over the years, this provision from the Meiji Civil Code was carried over substantially unchanged into Article 779 of the current (post-WWII) Civil Code. [cite: 1]

Contrasting with Family Register (戸籍, Koseki) Practices:

Interestingly, the administrative practice surrounding Japan's family registration system (koseki) had, from the outset and continuously, operated on the "automatic arising principle" for maternal relationships. [cite: 1] The Family Register Act:

- Assigns the duty of filing a birth notification for a child born out of wedlock to the mother (Article 52, Paragraph 2). This presupposes that a legal mother-child relationship is already in existence for her to have this obligation. [cite: 1] If the acknowledgment principle were strictly applied, the mother would be obligated to register a birth before her legal maternity was even established by acknowledgment.

- Details the specifics for a father's acknowledgment registration (Article 60) but notably lacks corresponding detailed provisions for a mother's acknowledgment registration. This suggests that the law does not anticipate maternal acknowledgment as a routine or necessary step for establishing the basic mother-child link. [cite: 1]

- Furthermore, a 1947 amendment to the Family Register Act mandated the attachment of a birth certificate to the birth notification (Article 49, Paragraph 3). [cite: 1] These birth certificates, typically completed by attending medical professionals, include the mother's name, thereby directly linking the child to the birthing mother through official documentation from the moment of birth. [cite: 1]

Evolution from Earlier Court Precedents:

Before the 1962 Supreme Court ruling, the Daishin'in (大審院, Japan's highest court prior to WWII) had largely adhered to the acknowledgment principle for maternal relationships:

- A Daishin'in judgment from December 9, 1921 (Taisho 10), held that even if a blood relationship existed between a mother and her child born out of wedlock, no legal mother-child relationship arose without acknowledgment. [cite: 1] This created situations where children, whose births were registered by their mothers but who were not separately "acknowledged," effectively had no legal mother and could not enjoy rights like parental care, support, or inheritance from her. [cite: 1]

- Recognizing the harshness of this stance, a subsequent Daishin'in ruling on March 9, 1923 (Taisho 12), while still upholding the acknowledgment principle, found that a mother's act of filing a birth registration for her child could also be deemed to have the effect of an acknowledgment. [cite: 1] This provided a practical way to recognize legal maternity for many children.

- However, if neither birth registration nor acknowledgment was made by the mother, the problem persisted. A Daishin'in decision on January 30, 1928 (Showa 3), maintained that no legal mother-child relationship arose without acknowledgment. Yet, it also held that the woman who gave birth, by virtue of that fact, still bore a duty of support towards the child, reasoning that she qualified as a "lineal ascendant" (under former Civil Code Article 954, similar to the current Article 877 concept of "lineal blood relatives" who owe each other support). [cite: 1]

These Daishin'in rulings, attempting to navigate the tension between the statutory language of acknowledgment and the realities of maternal bonds, drew significant criticism from legal scholars. [cite: 1]

The 1962 Supreme Court's Clear Shift:

The 1962 Supreme Court decision explicitly changed this trajectory. [cite: 1] It clearly stated that, as a rule, the maternal link with a child born out of wedlock is established by the fact of birth itself, distinguishing it from the paternal link with such a child, where the father's acknowledgment remains crucial. [cite: 1]

Consequentially:

- Disputes concerning the maternal relationship with a child born out of wedlock are typically resolved through a "suit for confirmation of the existence/non-existence of a parent-child relationship" (親子関係存否確認の訴え). [cite: 1]

- If a child seeks to establish maternity after the mother's death, they can file such a suit against the public prosecutor as the defendant. This differs from the procedure for posthumous paternal acknowledgment (Civil Code Article 787), which has strict time limitations (typically three years from the father's death). [cite: 1] These time limits do not apply to establishing maternity. (This was affirmed in a later Supreme Court case on March 29, 1974). [cite: 1]

- Furthermore, protections afforded to third parties who may have acquired rights before a posthumous paternal acknowledgment is finalized (Civil Code Articles 784 proviso and 910) are not analogously applied if a maternal relationship is confirmed after the mother's death and her estate has already been divided. (Supreme Court decision, March 23, 1979). [cite: 1]

The "General Principle" and Its "Exceptions" (or Lack Thereof):

The 1962 ruling stated that birth establishes maternity "as a general principle" (原則として). [cite: 1] It did not explicitly detail what circumstances might constitute an "exception" where maternal acknowledgment would still be necessary. [cite: 1] Critically, however, in the decades following this landmark decision, no subsequent Supreme Court case has emerged that actually identified such an exception or required a mother's separate acknowledgment to establish her legal tie to her child born out of wedlock. [cite: 1]

Prevailing Academic Opinion:

Even before 1962, while a minority of scholars supported the acknowledgment principle based on the perceived legislative intent, the majority were critical of the Daishin'in's stance. [cite: 1] They argued that the "automatic arising principle" (maternity from birth) caused no practical problems and that requiring acknowledgment created an illogical contradiction where an obvious biological and social maternal bond was not recognized in law. [cite: 1]

Within this majority favoring the automatic arising principle, some nuanced views existed:

- The "conditional automatic arising theory" (条件付当然発生説, jōken-tsuki tōzen hassei setsu) proposed that while maternity generally arose from birth, maternal acknowledgment could be an exception in objectively unclear situations, such as with an abandoned child whose birthing mother was unknown. [cite: 1]

- The "pure automatic arising theory" (当然発生説, tōzen hassei setsu) argued that acknowledgment was never necessary for the mother; the relationship always arose from the fact of birth, even in cases like abandoned children (though proving the fact of birth by a specific woman would be the challenge). [cite: 1]

After the 1962 Supreme Court decision, the pure automatic arising theory became the widely accepted view in legal scholarship, and academic debate concerning the necessity of a mother's acknowledgment largely subsided. [cite: 1]

The "Birthing Person = Mother" Rule in the Age of Modern Science

The 1962 judgment was delivered in an era when it was assumed that the woman who gave birth to a child was also unequivocally her genetic mother. [cite: 1] However, the advent of assisted reproductive technologies (ART) has introduced scenarios where this is not the case, such as:

- The use of donated ova (egg donation), where the gestational mother carries a fetus conceived with an egg from another woman. [cite: 1]

- Surrogacy arrangements, where one woman carries and gives birth to a child for another individual or couple. [cite: 1]

These developments raise the question: if the woman who gives birth is genetically unrelated to the child, does the principle "birth establishes motherhood" still hold?

The Japanese Supreme Court addressed this in a decision on March 23, 2007 (Heisei 19). It affirmed that the existing legal framework concerning parent-child relationships, for both marital and non-marital children, including those born via surrogacy, is based on the criterion that "the woman who gestates and gives birth to a child is that child's mother." [cite: 2] This is often referred to as the "birthing person = mother" rule (分娩者=母ルール, bunbensha = haha rūru). [cite: 2] The Court's rationale included:

- The Civil Code's provisions on presumption of legitimacy for children born in wedlock (e.g., Article 772, Paragraph 1) are predicated on the understanding that the maternal relationship is established through the objective facts of gestation and birth. [cite: 2]

- The 1962 Supreme Court ruling (the subject of this article) supports this for children born out of wedlock. [cite: 2]

- Ensuring the early and unambiguous determination of the legal mother-child relationship at the time of birth serves the child's welfare. [cite: 2]

In a contrasting situation, a Supreme Court decision on July 7, 2006 (Heisei 18), did allow a non-gestational woman to be recognized as the legal mother. This occurred when a claim by the woman listed as the mother on the family register (who was not the birth mother due to a false registration of the child as her own legitimate child) to have the parent-child relationship nullified was dismissed as an abuse of rights. [cite: 2] This, however, represents an exceptional circumstance based on the specific legal doctrine of abuse of rights.

More recently, specific legislation has addressed ART. The "Act on Special Provisions of the Civil Code Concerning Parent-Child Relationships with Children Born Through Assisted Reproductive Technology" (Law No. 76 of Reiwa 2, 2020) explicitly states in Article 9: "When a woman gestates and gives birth to a child using an ovum from another woman through assisted reproductive technology, the woman who gave birth shall be the child's mother." [cite: 2] This law codifies the "birthing person = mother" rule for children born via ART using donated eggs, reinforcing the principle established by case law. [cite: 2]

Emerging Challenges: Anonymous and Confidential Births

The "birthing person = mother" rule faces complex challenges from evolving social practices like anonymous and confidential births.

- Anonymous birth, legislated in countries like France, allows a woman to give birth without revealing her identity. [cite: 2]

- Confidential birth, legislated in Germany, allows a woman to disclose her identity only to the medical institution, which keeps it confidential under certain conditions. [cite: 2]

These systems, designed to protect vulnerable mothers and prevent desperate acts, inherently conflict with a straightforward application of the "birthing person = mother" rule if the goal is to immediately and publicly link the birth mother to the child via the family register. [cite: 2]

In Japan, these issues have come to the fore with initiatives like the one by Jikei Hospital in Kumamoto City, which announced its intention to implement a confidential birth system. [cite: 2] The first such birth in Japan reportedly occurred there in 2021. [cite: 2] Initially, there were discussions about how to handle the birth registration, including the possibility of leaving the "mother's name" field blank. [cite: 2] The Legal Affairs Bureau provided an opinion that a child's family register could be created by the municipal mayor under their official authority, even without a standard birth notification from the parents. [cite: 2] Following this, Kumamoto City created a separate, individual family register for a child born under this system. [cite: 2] On September 30, 2022, the Japanese government released its first set of national guidelines concerning confidential births, indicating an ongoing effort to navigate these sensitive issues. [cite: 2]

Conclusion: A Lasting Legacy

The Supreme Court's 1962 ruling was a quiet revolution in Japanese family law. By definitively stating that the act of birth, as a general principle, establishes the legal bond between a mother and her child born out of wedlock, the Court swept away decades of legal ambiguity and aligned the law more closely with biological reality and prevailing social understanding. This decision not only simplified the determination of maternity but also provided a foundational principle that has since been adapted and reaffirmed in the context of modern assisted reproductive technologies. While new challenges, such as confidential births, continue to test the contours of this rule, the 1962 judgment remains a cornerstone, underscoring the profound legal significance of the act of giving birth in defining motherhood in Japan.