Born Abroad via Surrogate: A Japanese Couple's Quest for Legal Parentage and the Supreme Court's Stance

Judgment Date: March 23, 2007 (Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench)

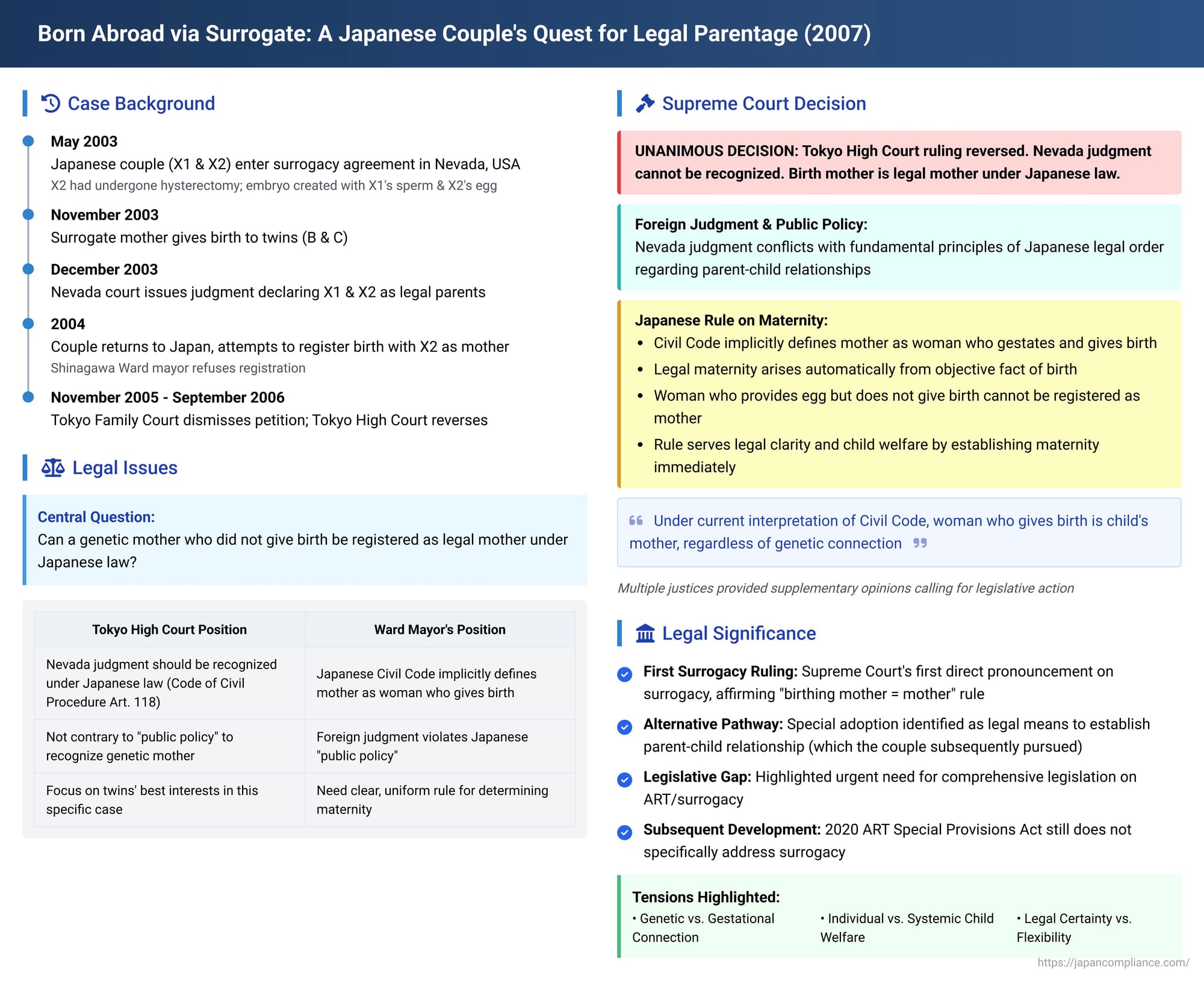

In a case that captured significant public and legal attention, Japan's Supreme Court issued a landmark decision in 2007 concerning the legal parentage of children born to a surrogate mother abroad using the gametes of a Japanese couple. The ruling addressed profound questions about the definition of motherhood in an era of advanced assisted reproductive technologies (ART) and the extent to which Japanese courts would recognize foreign judgments that conflict with domestic legal principles. The Court ultimately affirmed that, under Japanese law, the woman who gives birth is the legal mother, irrespective of genetic connection, a decision that has had lasting implications for individuals seeking to build families through international surrogacy.

A Couple's Journey: Surrogacy in Nevada

The case involved a Japanese married couple, Mr. X1 and Ms. X2. Ms. X2 had undergone a hysterectomy as part of cancer treatment, rendering her unable to carry a pregnancy. Seeking to have children genetically related to both of them, they pursued surrogacy. In May 2003, they entered into a surrogacy agreement with Ms. A, a woman residing in Nevada, USA. An embryo created using Mr. X1's sperm and Ms. X2's egg was implanted in Ms. A's uterus.

In November 2003, Ms. A gave birth to twins, B and C. Nevada state law, at the time, had provisions that recognized certain surrogacy agreements as valid and established the commissioning couple as the legal parents of the child born under such an arrangement. Following the twins' birth, a Nevada court, upon the petition of Mr. X1 and Ms. X2, issued a judgment in December 2003 confirming them as the biological and legal parents of B and C (referred to as "the Nevada judgment").

The Return to Japan and the Birth Registration Challenge

Armed with the Nevada judgment and their newborn twins, Mr. X1 and Ms. X2 returned to Japan. They attempted to register the births of B and C with Mr. Y, the mayor of Shinagawa Ward in Tokyo, naming Mr. X1 as the father and Ms. X2 as the mother on the birth notification forms. However, the ward mayor refused to accept these registrations. The refusal was based on the fact that Ms. X2 had not given birth to the children. The couple, being well-known public figures who had openly shared their surrogacy journey, found their path to legal recognition in Japan blocked.

In response, Mr. X1 and Ms. X2 petitioned the Tokyo Family Court, seeking an order compelling the ward mayor to accept the birth notifications.

Differing Views in the Lower Courts

The legal battle saw divergent outcomes in the lower courts:

- Tokyo Family Court (November 30, 2005): Dismissed the couple's petition. The court held that, according to the interpretation of the Japanese Civil Code, the woman who gives birth to a child is considered the legal mother.

- Tokyo High Court (September 29, 2006): Reversed the Family Court's decision. While the High Court acknowledged that Japanese law generally identifies the birth mother as the legal mother, it focused on whether the Nevada judgment could be recognized in Japan under Article 118 of the Code of Civil Procedure, which governs the recognition of foreign judgments. The High Court found that recognizing the Nevada judgment, which declared Mr. X1 and Ms. X2 the legal parents, would not violate Japan's public policy (a key condition for recognition under Article 118(3)). It deemed it appropriate in this specific case for Mr. X1 and Ms. X2 to be recognized as the children's legal parents and ordered the ward mayor to accept the birth notifications.

The ward mayor, Mr. Y, then appealed the High Court's ruling to the Supreme Court with permission.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Decision: The "Birthing Mother Rule" Prevails

The Supreme Court unanimously overturned the Tokyo High Court's decision and reinstated the Tokyo Family Court's original dismissal of the couple's petition. This meant the birth registrations naming Ms. X2 as the mother could not be accepted.

The Court's core reasoning was:

1. Foreign Judgment Recognition and Public Policy:

A foreign court judgment, even if valid in its country of origin, cannot be recognized in Japan if its content conflicts with the fundamental principles or basic ideals of Japan's legal order. This is encapsulated in the "public order" clause of Article 118(3) of the Code of Civil Procedure. The Supreme Court found that recognizing a foreign judgment that establishes a legal parent-child relationship not permissible under Japanese law—specifically, recognizing Ms. X2 as the mother when she did not give birth—would indeed contravene Japan's public order.

2. Japanese Law Defines Maternity by Birth ("Gestational Motherhood"):

The Court then elaborated on how Japanese law determines maternity:

- The Civil Code, particularly provisions like Article 772(1) (which deals with the presumption of a husband's paternity for a child born to his wife), implicitly assumes that the woman who conceives and gives birth is the child's mother. This legal mother-child relationship arises naturally and automatically from the objective facts of gestation and birth.

- This principle extends to children born outside of marriage. The Supreme Court referenced its own 1962 precedent (Supreme Court, April 27, 1962), which established that a mother's legal relationship with her non-marital child arises directly from the fact of birth, without needing a separate act of acknowledgment.

- The Court acknowledged that while Japan's parent-child laws are fundamentally based on biological (blood) ties, the specific rule making the birth mother the legal mother was established at a time when the woman who gestated and gave birth was, without exception, also the child's genetic mother. This rule, based on the objective and externally clear fact of birth, was also seen as serving the child's welfare by promptly and unequivocally establishing the maternal link at the moment of birth.

- Considering that parent-child relationships are of profound public interest, deeply affect child welfare, and must be determined uniformly by clear criteria, the Court concluded that under the current interpretation of the Civil Code, the woman who gestates and gives birth to a child must be considered that child's mother. Consequently, a legal maternal relationship cannot be recognized with a woman who did not gestate or give birth to the child, even if she provided the egg used for conception (as Ms. X2 did).

Based on this reasoning, the Supreme Court held that the Nevada judgment, by identifying Ms. X2 as the legal mother of B and C, was contrary to Japan's public order and thus could not be recognized in Japan. As a result, under Japanese law, no maternal relationship was established between Ms. X2 and the children, and therefore, a legitimate parent-child relationship between Mr. X1 and Ms. X2 (as a married couple) and the twins could not be registered in the manner they had sought.

Supplementary opinions were provided by Justices Furuta Yuki, Tsuno Osamu, and Imai Isao, further exploring the complexities of the issue and the need for legislative action.

Significance: Affirming the "Birthing Mother = Mother" Rule in Surrogacy

This 2007 decision was the Supreme Court's first direct pronouncement on surrogacy. Its most significant impact was the clear affirmation of the "birthing mother = mother" rule (sometimes called the "gestational motherhood principle") as the standard under Japanese law, even in the context of gestational surrogacy where the commissioning mother is the genetic mother.

The Academic and Legal Debate on Maternity

The Supreme Court's stance aligns with the majority view among Japanese legal scholars, who argue that defining the birth mother as the legal mother offers the most clarity and stability. The reasons often cited include:

- The objective and easily ascertainable nature of birth allows for immediate and unequivocal determination of maternity.

- The process of gestation and childbirth is seen as fostering a maternal bond.

However, minority views exist, proposing alternative criteria for determining legal motherhood in ART scenarios:

- Genetic Link: Some argue that since Japanese parent-child law is generally rooted in blood ties, the genetic mother should be recognized as the legal mother.

- Intent of the Parties: Others suggest that the intent of the commissioning parents should be paramount, drawing parallels to situations in Japanese family law where intent can play a decisive role (e.g., a husband's consent to Artificial Insemination by Donor (AID) generally estops him from denying paternity).

A common critique of applying the traditional "birthing mother = mother" rule to surrogacy is that this rule was developed when it was inconceivable for the gestational mother and the genetic mother to be different women.

The Nuance of "Child Welfare"

The concept of "child welfare" was invoked by both sides and interpreted differently:

- Systemic Child Welfare: The Supreme Court emphasized that establishing a clear, predictable, and universally applicable rule for maternity serves the welfare of all children by ensuring legal relationships are determined promptly and unequivocally at birth.

- Individual Child Welfare: The Tokyo High Court, in contrast, focused on the specific circumstances of B and C. Given that Mr. X1 and Ms. X2 were their genetic parents, were raising them, and intended to continue doing so, while the surrogate Ms. A had no intention of being their parent, denying legal recognition to Ms. X2 as the mother seemed contrary to B and C's immediate best interests.

Adoption: An Alternative Legal Pathway

The supplementary opinions from Justices Tsuno and Furuta in the Supreme Court decision pointed towards special adoption as a viable legal means for Mr. X1 and Ms. X2 to establish a legal parent-child relationship with B and C. It has been reported that Mr. X1 and Ms. X2 subsequently did pursue and successfully complete special adoptions for the twins. There are other published Japanese court decisions where special adoption has been granted in both domestic and international surrogacy cases.

Legislative Landscape: Post-Decision Developments (and Remaining Gaps)

At the time of the 2007 ruling, Japan had no specific laws regulating surrogacy or defining parentage for children born through such arrangements. This legal vacuum was a central theme in the Supreme Court's call for legislative action.

Since then, there has been some movement:

- The "Act on Special Provisions of the Civil Code Concerning Parent-Child Relationships with Children Born Through Assisted Reproductive Technology" (Law No. 76 of Reiwa 2) was enacted in 2020, with its parentage-related provisions taking effect on December 11, 2021.

- This Act establishes basic principles for ART and provides special rules for parentage when third-party sperm or eggs are used.

- However, due to significant ongoing debate and lack of consensus, the 2020 Act does not include specific provisions on surrogacy arrangements or the parentage of children born via surrogacy.

- Nevertheless, Article 9 of the Act, which addresses egg donation, states: "When a woman gestates and gives birth to a child using an ovum from another woman through assisted reproductive technology, the woman who gave birth shall be the child's mother". Legal commentators suggest this provision is likely to be interpreted as reinforcing the "birthing mother = mother" rule even in surrogacy situations where the egg might come from the commissioning mother or another donor.

- The 2020 Act includes an accessory provision (Article 3, Paragraph 1) mandating further review and consideration of regulations concerning surrogacy, indicating that legislative discussion on this complex issue is expected to continue.

Conclusion: A Principled Stand and a Continuing Dialogue

The 2007 Supreme Court decision delivered a clear message: under the existing interpretation of Japanese Civil Law, maternity is established by gestation and birth. This "birthing mother = mother" rule means that a commissioning mother who provides her egg but does not carry the pregnancy cannot be registered as the legal mother in Japan, and foreign judgments to the contrary will not be recognized if they violate this fundamental principle of Japanese public order.

While providing legal certainty on this specific point, the ruling also underscored the urgent need for comprehensive legislation to address the multifaceted legal, ethical, and social issues arising from surrogacy and other advanced assisted reproductive technologies. The path for Japanese couples using international surrogacy to achieve legal parentage in Japan often involves subsequent adoption procedures. The societal and legal dialogue surrounding how best to protect the welfare of children born through ART, while also considering the desires of those seeking to become parents, continues.