Board Meeting Blunders: Can a Resolution Be Saved if an Unnotified Director Wouldn't Have Changed the Vote? A Japanese Supreme Court Analysis

Case: Action for Payment on Promissory Notes

Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench, Judgment of December 2, 1969

Case Number: (O) No. 1144 of 1968

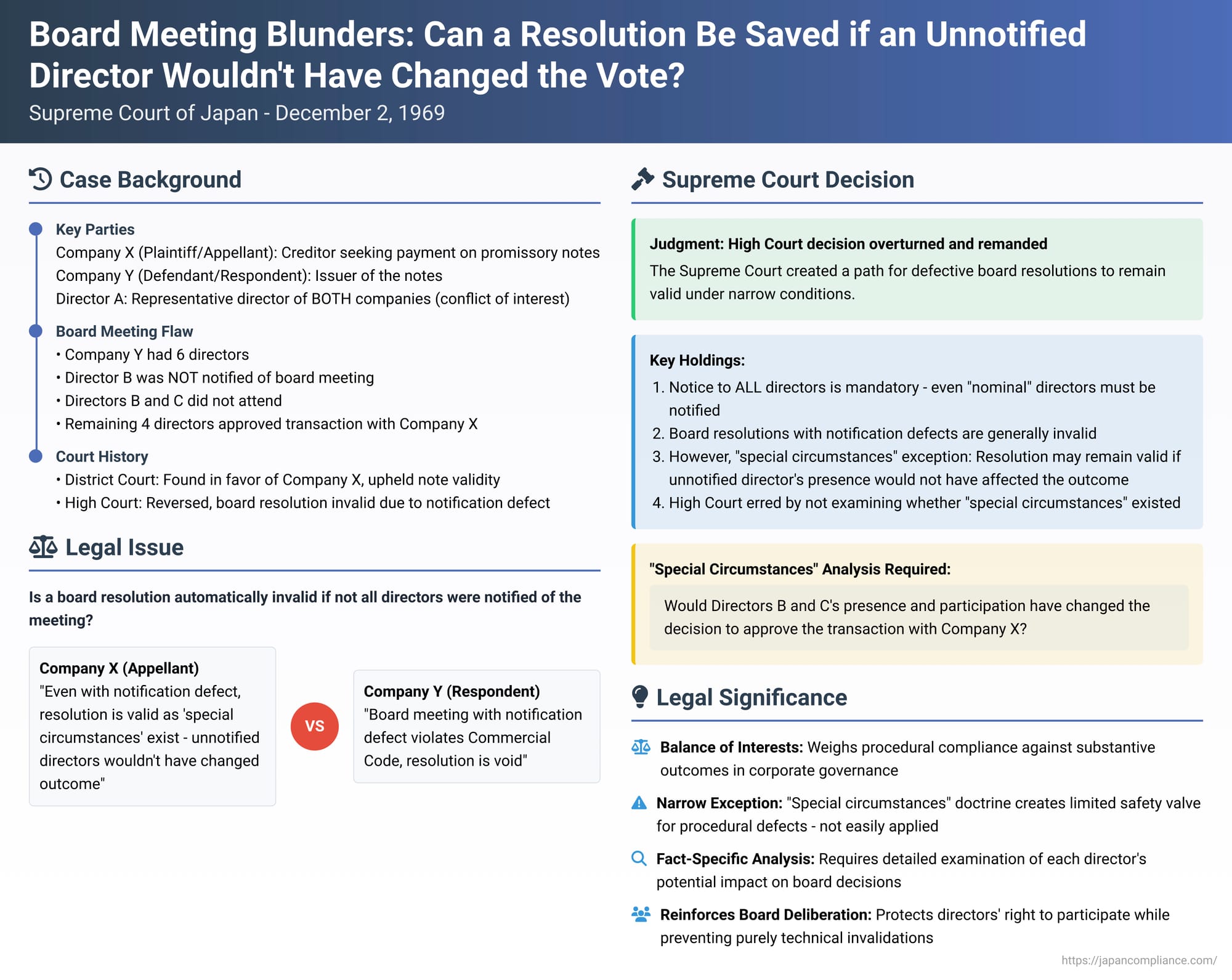

The board of directors is a cornerstone of corporate governance in Japan, serving as the key decision-making and supervisory body. For a board to function effectively and for its resolutions to be valid, proper procedures must be followed in convening its meetings. A fundamental requirement is that all directors receive due notice, ensuring each member has the opportunity to participate, deliberate, and vote. But what happens if this crucial procedural step is missed for one or more directors? Is a resolution passed at such a defectively convened meeting automatically void? A significant Supreme Court decision on December 2, 1969, addressed this very issue, establishing that while such a defect generally invalidates a resolution, there might be "special circumstances" under which the resolution can still be upheld.

A Disputed Debt and a Flawed Board Meeting: Facts of the Case

The case arose from a claim by Company X (the plaintiff/appellant) against Company Y (the defendant/respondent) for payment on two promissory notes drawn by Company Y.

Company Y, while admitting to the issuance of the notes, raised several defenses. The most pertinent to the Supreme Court's ultimate decision was a claim related to a conflict of interest and lack of proper board approval:

- At the time the underlying debt was incurred and the initial promissory notes (for which the current notes were renewals) were issued, an individual named A was the representative director of both Company Y (the debtor) and Company X (the creditor).

- Company Y argued that because of this dual role held by A, the transaction (a loan from Company X to Company Y and the issuance of notes by Y to X) constituted a conflict-of-interest transaction. Such a transaction required the explicit approval of Company Y's board of directors under the then-Commercial Code.

- Company Y asserted that this necessary board approval was either entirely lacking or, if a meeting was held, it was procedurally flawed and its resolution invalid.

Company X countered these arguments. It maintained that the notes were indeed issued for a legitimate loan from Company X to Company Y, and that both this loan and the initial issuance of promissory notes had received the necessary approval from Company Y's board of directors.

However, the validity of that crucial board meeting of Company Y became a central point of contention. According to Company X's submissions:

- Company Y had six directors at the relevant time.

- One director, B, was allegedly not sent a convocation notice for the board meeting where the approval was supposedly given.

- Two directors, B (who was not notified) and another director, C, did not attend this board meeting.

- The remaining four directors did attend, and the resolution approving the transaction with Company X was passed.

- Company X further alleged that directors B and C, within a few days after the meeting, had subsequently approved the content of the resolution.

The Lower Courts' See-Saw Rulings

The court of first instance (Tokyo District Court) ruled in favor of Company X, upholding its claim for payment on the notes. The District Court found that although director B (and possibly C) were not properly notified or did not attend the board meeting, director B was merely a "nominal" director. It concluded that even if B and C had been properly notified and had attended the meeting, their presence and votes would not have affected the outcome of the board's decision to approve the transaction. Thus, the approval was deemed valid under these "special circumstances."

The Tokyo High Court, however, reversed this decision. It found that the convocation procedure for Company Y's board meeting was fatally flawed because it violated the then-Commercial Code Article 259-2 (a provision corresponding to Article 368, Paragraph 1 of the current Companies Act, which mandates proper notice to directors). Specifically, the failure to notify director B was a critical defect. Consequently, the High Court held that the board resolution approving the loan and note issuance was invalid. Without valid board approval, the underlying loan agreement and the issuance of the promissory notes were also deemed void, absolving Company Y of liability. The High Court also noted a lack of evidence that the renewal notes themselves had received any specific board approval.

Aggrieved by the High Court's ruling, Company X appealed to the Supreme Court. It reiterated its arguments that director B was merely nominal and thus notice to him wasn't essential, and that, in any event, given Company Y's financial situation and need for funds from Company X, the attendance of B and C at the board meeting would not have altered the decision to approve the transaction.

The Supreme Court's Intervention: Focusing on "Special Circumstances"

The Supreme Court overturned the High Court's decision and remanded the case back to the High Court for further proceedings.

Reasoning of the Apex Court: A Path to Validate, If Conditions Met

The Supreme Court's judgment meticulously addressed the legal principles involved:

- Notice to All Directors is a Mandatory Requirement: The Court first firmly rejected Company X's argument that "nominal" directors do not need to be notified of board meetings. It stated that Article 259-2 of the then-Commercial Code clearly requires convocation notices to be sent to all directors. There is no reasonable legal basis for excluding directors from this requirement simply because they might be perceived as "nominal" or less active. (Thus, the High Court was correct in finding a procedural defect).

- Defective Notice Generally Voids the Board Resolution: The Supreme Court then affirmed the general principle: If a board of directors' meeting is convened with a procedural defect, such as failing to provide proper convocation notice to some of its members, any resolution passed at such a defectively convened meeting is, in principle, invalid.

- The "Special Circumstances" Lifeline – An Exception to the Rule: However, the Court introduced a critical exception to this general rule. It held that even if a convocation defect exists, the resolution passed at that meeting can still be considered valid if there are "special circumstances" (特段の事情 - tokudan no jijō) under which it can be recognized that the attendance of the unnotified director(s) would still not have affected the outcome of the resolution. In making this point, the Supreme Court explicitly referenced one of its own prior judgments (a 1964 Second Petty Bench decision concerning a cooperative association, which had laid down a similar principle).

- The High Court's Procedural Misstep – Failure to Consider "Special Circumstances": The Supreme Court noted that the court of first instance (the District Court) had applied this "special circumstances" principle. The District Court had made factual findings suggesting that director B was indeed largely nominal and that, consequently, even if both B and C had been properly notified and had attended the board meeting, their presence would not have changed the board's decision to approve the transaction with Company X.

Company X, in its arguments before the High Court, had explicitly relied on these findings from the first instance judgment and had maintained that the board resolution was valid due to these "special circumstances."

The Supreme Court found that the High Court had erred by not properly addressing this crucial argument. The High Court had limited its findings to the fact that director B was not notified, that B and C did not attend, and that there was no evidence they later ratified the resolution. Based on these limited findings, the High Court had simply concluded that the board resolution was invalid due to the notice defect. It failed to make any specific determination or ruling on Company X's assertion of "special circumstances" – specifically, whether the presence and potential votes of B and C would have made any difference to the outcome.

This failure by the High Court to rule on a material argument presented by Company X constituted an "omission of judgment" (handan itatsu). Since the determination of whether such "special circumstances" existed could directly affect the validity of the board resolution and thus the final outcome of the case (Company Y's liability on the notes), the High Court's judgment could not stand. - Remand for Further Examination: Consequently, the Supreme Court remanded the case to the Tokyo High Court, instructing it to conduct a proper examination and make a determination on the existence or non-existence of the "special circumstances" alleged by Company X.

Analysis and Implications: The Delicate Balance in Board Procedures

This 1969 Supreme Court decision is a significant ruling in Japanese corporate law, establishing an important, albeit narrowly construed, exception to the general rule that procedural flaws in convening a board meeting invalidate its resolutions.

- The Sanctity of Board Meeting Procedures:

The judgment underscores the fundamental importance of adhering to proper procedures when convening board meetings. The board of directors, as a collective body (now governed by provisions like Companies Act Article 362), makes decisions through deliberation and voting. Providing every director with proper notice and an opportunity to attend (as mandated by Article 368, Paragraph 1 of the current Companies Act, which generally requires notice one week prior, though this can be shortened by the articles of incorporation) is essential for the integrity of this deliberative process. Failure to do so deprives directors of their right to participate, to contribute their knowledge and experience, and to influence the board's decisions. - The "Special Circumstances" Exception – A Narrow Opening:

The core of this judgment lies in its recognition that, despite a procedural defect like failing to notify a director, a board resolution might still be upheld if it can be definitively shown that the defect had no bearing on the outcome. This principle had been hinted at in a 1964 Supreme Court case concerning cooperative associations and was confirmed for stock companies by this 1969 decision, and later reaffirmed in a 1990 Supreme Court case (Case 39 in some compilations).

However, this exception is generally viewed by legal commentators as one that should be applied very cautiously and strictly. - Academic Debate and Judicial Application of "Special Circumstances":

The "special circumstances" doctrine has been a subject of considerable academic debate:- Arguments Against Easy Application: Many scholars are critical of a lenient application of this exception. They argue that it's often speculative, if not impossible, to definitively conclude that an absent director's participation (including their arguments and persuasive efforts) would not have changed the minds of other directors and thus altered the outcome of the vote. If the exception is applied too readily, it risks undermining the very purpose of the board as a deliberative body and could allow companies to strategically exclude certain directors from meetings where contentious issues are to be decided. The failure to notify a director is, by its nature, a grave defect as it denies them their fundamental right to participate in governance.

- Arguments for Conditional Application: Other scholars, while acknowledging the risks, concede that there might be truly exceptional situations where upholding a resolution despite a minor notice defect is justifiable to prevent a purely formalistic invalidation, especially if the outcome was a clear foregone conclusion and no substantive prejudice occurred.

- What Might Qualify as "Special Circumstances"?

The Supreme Court in this 1969 decision (and the related 1964 and 1990 decisions) did not provide an exhaustive list of what constitutes "special circumstances." Lower courts and academic writings have since explored various scenarios, including:It must be emphasized that many of these examples are highly fact-specific and could be problematic if applied broadly, as they risk undermining the fundamental principles of board deliberation and collective responsibility. Legal commentary often expresses skepticism about easily establishing such "special circumstances." For instance, the argument that a director is merely "nominal" and therefore their absence is inconsequential was explicitly rejected by the Supreme Court as a basis for dispensing with the notice requirement itself.- Situations where the unnotified director had effectively already resigned or had consistently and demonstrably delegated their decision-making authority to other directors and had a pattern of non-attendance.

- Cases where the unnotified director was in such profound and irreconcilable conflict with the majority of the board that their participation was certain to be disruptive rather than constructive, and the voting outcome was mathematically predetermined by the entrenched majority. (This is a particularly controversial scenario, as it could be used to marginalize directors with dissenting views).

- Instances where the unnotified director subsequently and unequivocally consented to the resolution (though this is often seen more as a "curing" of the defect rather than a "special circumstance" ab initio; the Supreme Court in this case noted the High Court found no such subsequent approval by B and C).

- Mathematical certainty: For example, if all notified directors (constituting a clear quorum and voting majority) unanimously passed the resolution, and the number of unnotified directors was so small that even if they had all attended and voted against the measure, it would still have passed by the required majority. (This, too, is debated, as it doesn't account for the potential persuasive power of the absent directors' arguments during deliberation).

- If the unnotified director's known and consistent stance on the issue was aligned with the resolution passed, or if their influence within the board was demonstrably negligible, and their presence was highly unlikely to sway the strong, pre-existing views of the decisive majority.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's decision of December 2, 1969, carves out a narrow but important exception to the rule that defective convocation procedures invalidate board of directors' resolutions. While affirming the fundamental requirement to notify all directors of board meetings (including those who might be considered "nominal"), the Court acknowledged that a resolution passed despite a notice defect is not irrevocably void. It can be upheld if "special circumstances" convincingly demonstrate that the unnotified director's attendance and participation would have had no impact on the resolution's outcome.

This ruling underscores a judicial attempt to balance procedural regularity with substantive fairness, preventing resolutions from being overturned on purely technical grounds if the defect truly had no practical effect on the decision. However, the burden of proving such "special circumstances" rests heavily on the party seeking to uphold the flawed resolution. The remand in this case highlighted the necessity for lower courts to meticulously examine the factual basis for any such claim before either invalidating or upholding a resolution passed under procedurally imperfect conditions. The decision remains a key reference for understanding the legal "safety valves" that may, in exceptional cases, preserve the validity of corporate decisions despite procedural missteps.