Board Discretion and Director Accountability in Japan: Insights from a 2024 Supreme Court Ruling

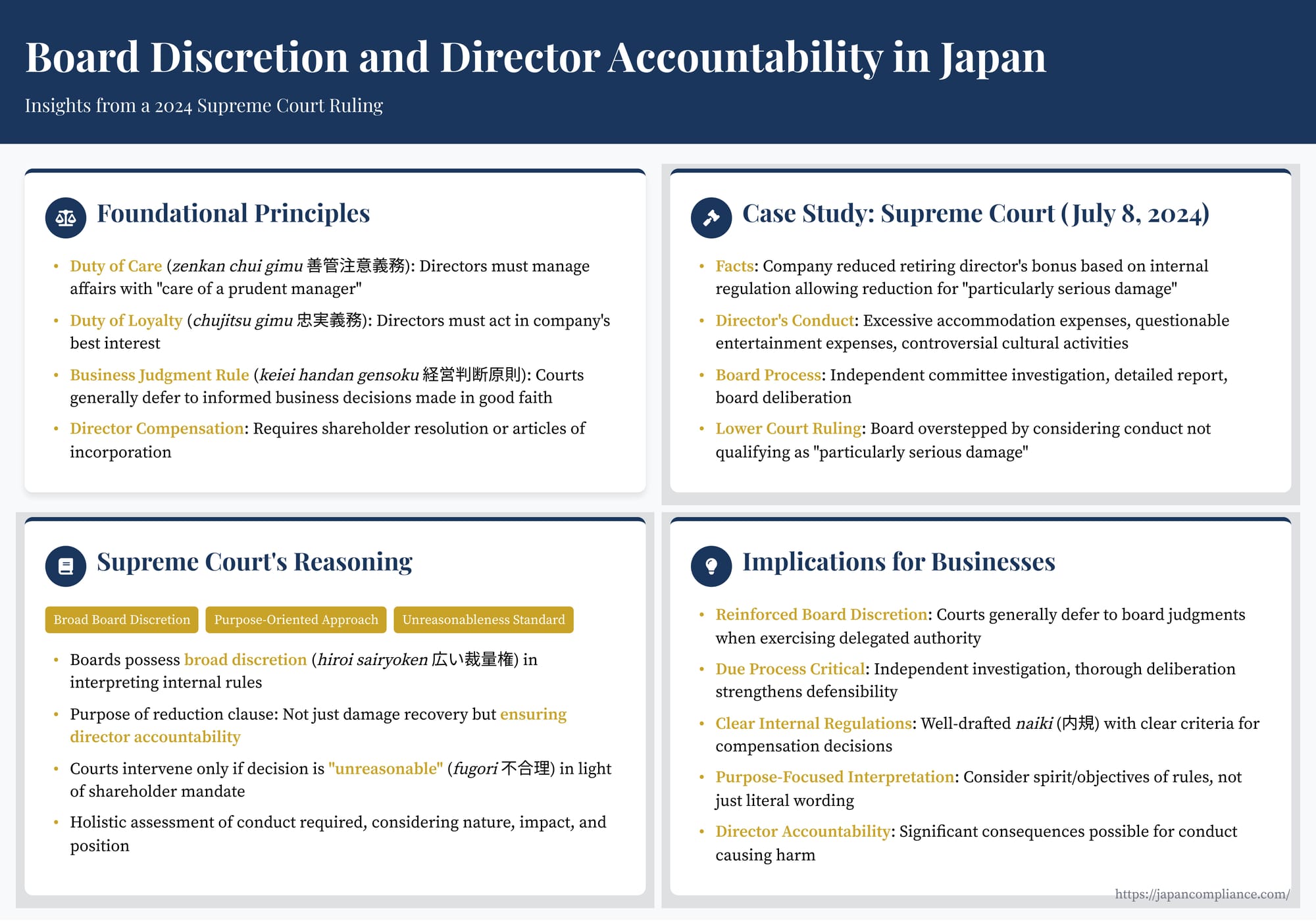

TL;DR: A 2024 Supreme Court ruling upheld a board’s discretion to slash a retiring director’s bonus after an external probe found serious misconduct. The decision confirms that Japanese courts defer to boards acting through proper process and clarifies how “business-judgment” deference interacts with directors’ duty of care and loyalty.

Table of Contents

- Introduction: Understanding Director Responsibilities in Japan

- Foundational Principles: Director Duties under Japan's Companies Act

- Focus Area: Director Compensation and Retirement Bonuses

- Case Study: Supreme Court Decision, July 8 2024 (Reiwa 6)

- Analysis and Implications for Businesses

- Conclusion

Introduction: Understanding Director Responsibilities in Japan

For international corporations with subsidiaries, joint ventures, or significant business dealings in Japan, a clear understanding of the duties and potential liabilities of company directors under Japanese law is essential for effective governance and risk management. Japan's Companies Act outlines the core responsibilities directors owe to their company, primarily the duty of care and the duty of loyalty. However, the practical application and scope of these duties, particularly concerning the discretionary decisions made by boards of directors, are often shaped by evolving case law.

A recent decision by the Supreme Court of Japan, issued on July 8, 2024, provides valuable insights into the extent of a board's discretion when implementing internal company regulations, specifically concerning the reduction of retirement bonuses for directors based on alleged misconduct. This ruling highlights the deference courts may show to board decisions made through proper processes, even when interpreting broad contractual or regulatory terms like "particularly serious damage." This article examines the foundational principles of director duties in Japan and analyzes this key 2024 Supreme Court case to draw implications for corporate governance and director accountability.

Foundational Principles: Director Duties under Japan's Companies Act

The legal framework governing directors' responsibilities in Japan primarily stems from the Companies Act (会社法, Kaishahō). Two fundamental duties are central:

- Duty of Care (善管注意義務, zenkan chūi gimu): Article 330 of the Companies Act stipulates that the relationship between a company and its directors is governed by the Civil Code provisions on mandate (delegation). This incorporates the duty defined in Article 644 of the Civil Code: directors must manage the company's affairs with the "care of a prudent manager." This standard requires directors to exercise the level of attention, diligence, and skill reasonably expected of someone in their position.

- Business Judgment Rule (経営判断原則, keiei handan gensoku): Japanese courts, while not having a formally codified rule like in some U.S. jurisdictions, generally apply a principle akin to the business judgment rule. Courts tend not to second-guess informed business decisions made by directors in good faith and with reasonable investigation, even if those decisions ultimately result in losses for the company, provided there was no clear violation of law or the articles of incorporation, and no conflict of interest.

- Duty of Loyalty (忠実義務, chūjitsu gimu): Article 355 of the Companies Act explicitly requires directors to perform their duties faithfully (chūjitsu ni) for the benefit of the company. This duty prohibits self-dealing and obliges directors to prioritize the company's interests over their own or those of third parties. While distinct from the duty of care, the two often overlap, with actions breaching the duty of loyalty frequently also constituting a breach of the duty of care.

Furthermore, the Board of Directors itself has a statutory duty to supervise the execution of duties by individual directors (Article 362(2)(ii)), adding another layer to the governance structure.

Focus Area: Director Compensation and Retirement Bonuses

Director compensation in Japan requires specific governance procedures.

- General Compensation: Article 361 of the Companies Act mandates that director compensation (amount, calculation method, specific details) must be stipulated in the articles of incorporation or approved by a resolution at a shareholders' meeting. In practice, shareholders often approve a total maximum amount or a calculation formula, delegating the determination of individual directors' compensation within those parameters to the board of directors or a compensation committee.

- Retirement Bonuses (退職慰労金, taishoku irōkin): These bonuses, traditionally paid upon a director's retirement to reward meritorious service, are generally considered a form of deferred compensation. As such, their payment typically also requires authorization via the articles or, more commonly, a shareholders' meeting resolution. Often, shareholders approve the principle of paying such bonuses according to established internal company regulations (内規, naiki), delegating the final decision on payment and the specific amount (within the rules) to the board of directors.

- Discretionary Reduction Clauses: These internal regulations governing retirement bonuses frequently include clauses granting the board discretion to reduce the standard amount or deny payment altogether under certain conditions. Common grounds include serious misconduct, breaches of duty, actions causing significant damage to the company, or dismissal for cause. The interpretation and application of such discretionary clauses, especially terms like "serious damage," can become contentious, as illustrated by the recent Supreme Court case.

Case Study: Supreme Court Decision, July 8, 2024 (Reiwa 6)

This case (Supreme Court, Reiwa 4 (Ju) No. 1780) revolved around the board's decision to reduce a retiring director's bonus based on internal rules.

Factual Background (Anonymized Summary)

- The Parties: The case involved a company ("Company Y") and its retiring Representative Director ("Director X").

- Internal Regulations: Company Y had internal regulations (naiki) governing director retirement bonuses. These regulations stipulated a standard calculation method (基準額, kijungaku) based on factors like final monthly remuneration but included a clause allowing the board to reduce this amount if the director had caused "particularly serious damage" (在任中特に重大な損害を与えた, zainin-chū tokuni jūdai na songai o ataeta) to the company during their tenure ("Reduction Clause").

- Director X's Conduct: During his long tenure, Director X engaged in several questionable activities:

- (Conduct 1) Receiving excessive accommodation expenses beyond company limits over many years and, upon discovery, shifting the associated tax burden to the company and increasing his own remuneration to effectively perpetuate the excessive payments. This conduct received media attention.

- (Conduct 2) Causing the company to incur high entertainment expenses and travel allowances over an extended period.

- (Conduct 3) Causing the company to incur substantial expenses for cultural and artistic support activities, the propriety of which was later questioned.

- Shareholder Resolution: At the shareholders' meeting where Director X's retirement became effective, a resolution was passed entrusting the decision regarding his retirement bonus to the board of directors, to be made in accordance with the internal regulations. The meeting chair (Director X himself) explained that the decision would follow an investigation by a neutral, independent committee.

- Independent Investigation: An independent committee composed of lawyers with no conflicts of interest was established. Its detailed report concluded:

- Conduct 1 raised suspicions of constituting aggravated breach of trust (特別背任罪, tokubetsu hainin-zai) under the Companies Act.

- Conduct 2 was unjustifiable.

- Conduct 3 was also deemed problematic (though less severe).

- Director X had caused substantial damage to Company Y through these actions (estimated at over JPY 350 million, with Conduct 3 accounting for over JPY 200 million of that estimate).

- The committee recommended that if the board decided to pursue criminal charges for Conduct 1, no bonus should be paid. If not pursuing charges, the board could, without breaching its duty of care, decide to pay a bonus amount calculated by deducting all or a significant part of the estimated damages from the standard bonus amount.

- Board Decision: The board deliberated based on the report. It ultimately decided not to pursue criminal charges against Director X for Conduct 1. It then resolved to pay Director X a reduced retirement bonus of JPY 57 million, calculated by deducting approximately 90% of the committee's estimated damage figure from the standard bonus amount (which was approx. JPY 377 million).

- Litigation: Director X sued Company Y and its current Representative Director (Director Y2), seeking damages equivalent to the deducted bonus amount. He argued the board had abused its discretion.

Lower Court Ruling (Fukuoka High Court, Miyazaki Branch)

The High Court ruled partially in favor of Director X. It held that Conduct 3 (cultural spending) could not reasonably be considered "particularly serious damage" under the Reduction Clause. Because the board, in calculating the reduction, had considered the expenses related to Conduct 3 (apparently following the damage calculation approach suggested by the investigation committee which included Conduct 3 damages), the High Court concluded that the board had misinterpreted or misapplied the Reduction Clause and its decision constituted an abuse of discretion exceeding the scope of authority delegated by the shareholders. The High Court ordered damages based on this finding.

The Supreme Court's Reversal (Decision of July 8, 2024)

The Supreme Court overturned the High Court's decision, ruling entirely in favor of Company Y. Its key reasoning included:

- Purpose of the Reduction Clause: The Court interpreted the purpose (趣旨, shushi) of the Reduction Clause not just as a mechanism for damage recovery but as a tool for the board, in its supervisory capacity, to impose appropriate sanctions on directors for misconduct, thereby ensuring the proper execution of directorial duties.

- Broad Board Discretion: Given this purpose, the Court affirmed that the board possesses broad discretion (広い裁量権, hiroi sairyōken) in determining (a) whether a retiring director's actions constitute "particularly serious damage" and (b) if so, the appropriate amount of reduction.

- Holistic Assessment Required: The board's determination should be based on a comprehensive consideration of relevant factors, including the nature and substance of the conduct causing damage, the impact on the company (financial, reputational, etc.), and the director's position and responsibilities.

- Standard of Judicial Review: A board's decision made under such delegated authority constitutes an abuse of discretion only if it is "unreasonable" (不合理, fugōri) when viewed in light of the purpose of the shareholder resolution delegating the authority. The Court explicitly stated that reasonableness, not absolute correctness, is the standard. (Legal commentary included in the PDF journal notes that while "unreasonable" might seem a lower threshold for intervention than "grossly unreasonable," in practice, given the board's broad discretion rooted in its supervisory function, a finding of unreasonableness would likely be confined to exceptional cases).

- Application to the Case Facts: The Supreme Court found the board's decision was not unreasonable. Several factors supported this conclusion:

- The problematic nature of Conduct 1 (excessive expenses, tax shifting, self-serving pay rise) and Conduct 2 (high entertainment/travel costs) was significant. The Court noted the reputational damage from media reports on Conduct 1.

- The board based its decision on a detailed report from a neutral, independent investigation committee. The Court found no indication the committee's information gathering was insufficient.

- The board conducted substantial deliberations before reaching its decision.

- Given these factors, the board's assessment that Conduct 1 and Conduct 2 caused substantial damage had a reasonable basis.

- Therefore, regardless of whether Conduct 3 constituted damage, the board's overall decision to significantly reduce the bonus based on the severity of Conduct 1 and Conduct 2 was not unreasonable in light of the shareholder mandate to apply the internal regulations. (The PDF commentary suggests the Supreme Court implicitly rejected the High Court's assumption that the board had mechanically applied the committee's damage calculation method, which was heavily influenced by Conduct 3 damages. Instead, the Supreme Court likely viewed the board's decision as being primarily justified by the seriousness of Conduct 1 and 2, which the committee had also flagged as potentially criminal).

Analysis and Implications for Businesses

This Supreme Court decision offers important clarifications and carries several implications for corporate governance in Japan:

- Reinforcement of Board Discretion: The ruling strongly reaffirms the wide latitude granted to boards of directors when exercising discretion delegated by shareholders, especially concerning compensation matters governed by internal rules. Courts will generally defer to the board's judgment unless it is shown to be "unreasonable" based on the mandate's purpose. A mere disagreement with the board's interpretation or application of internal rules is insufficient for judicial intervention.

- The Importance of Due Process: The Court placed significant weight on the fact that the board's decision was preceded by a thorough investigation conducted by an independent committee and involved substantial internal deliberation. This underscores the critical importance of procedural fairness, independence (where appropriate), and careful consideration when boards make sensitive decisions, particularly those involving potential sanctions or reductions in expected benefits for executives. A robust process strengthens the defensibility of the board's ultimate decision.

- Purpose-Oriented Interpretation of Rules: The Court emphasized interpreting the Reduction Clause based on its underlying purpose (ensuring director accountability) rather than solely on a narrow, literal reading of terms like "particularly serious damage." This suggests boards should consider the spirit and objective of internal regulations when applying them.

- Accountability for Director Conduct: The case serves as a clear reminder that director conduct causing significant harm (financial or reputational) can have tangible consequences, including substantial reductions in discretionary payments like retirement bonuses, even if the conduct does not lead to dismissal or criminal prosecution.

- Guidance for Governance Practices: For foreign companies operating in Japan, the decision highlights the need for:

- Clear Internal Regulations: Having well-drafted naiki or similar rules governing director compensation, bonuses, and standards of conduct, including clear (though potentially broad) criteria for forfeiture or reduction.

- Defined Board Procedures: Establishing clear processes for investigating alleged misconduct and for the board to exercise its discretion regarding compensation, potentially involving independent committees where conflicts exist.

- Understanding Judicial Deference: Recognizing the degree of deference Japanese courts afford to board decisions made reasonably and through proper procedures. Challenges to such decisions face a high bar ("unreasonableness").

Conclusion

The Supreme Court of Japan's July 8, 2024, decision provides significant guidance on the scope of board discretion in applying internal regulations related to director retirement bonuses and, by extension, director accountability. It reinforces the principle that courts will generally respect the business judgment of boards acting under shareholder delegation, provided the decisions are procedurally sound and not objectively "unreasonable" in light of the delegated mandate's purpose.

For directors serving Japanese companies and for the companies themselves (including foreign parent companies or joint venture partners), this case underscores the symbiotic relationship between robust governance processes and defensible board decisions. Clear internal rules, reliance on independent investigations where appropriate, thorough deliberation, and a focus on the purpose behind discretionary powers are key elements in navigating complex situations involving director conduct and compensation, thereby minimizing legal risks and upholding accountability.

- Share-Transfer Restrictions in Closely-Held Japanese Corporations

- Commitment Procedures in Japanese Antitrust

- Derivative vs. Original Acquisition of Rights in Japan

- Ministry of Justice — Q&A on Director Duties & Liability (JP)

https://www.moj.go.jp/MINJI/minji07_00160.html