Blue Form Fraud: How Retroactive Revocation Impacts "Evaded Tax Amount" in Japan

Date of Judgment: September 20, 1974

Case Name: Corporate Tax Act Violation Case (昭和47年(あ)第1344号)

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench

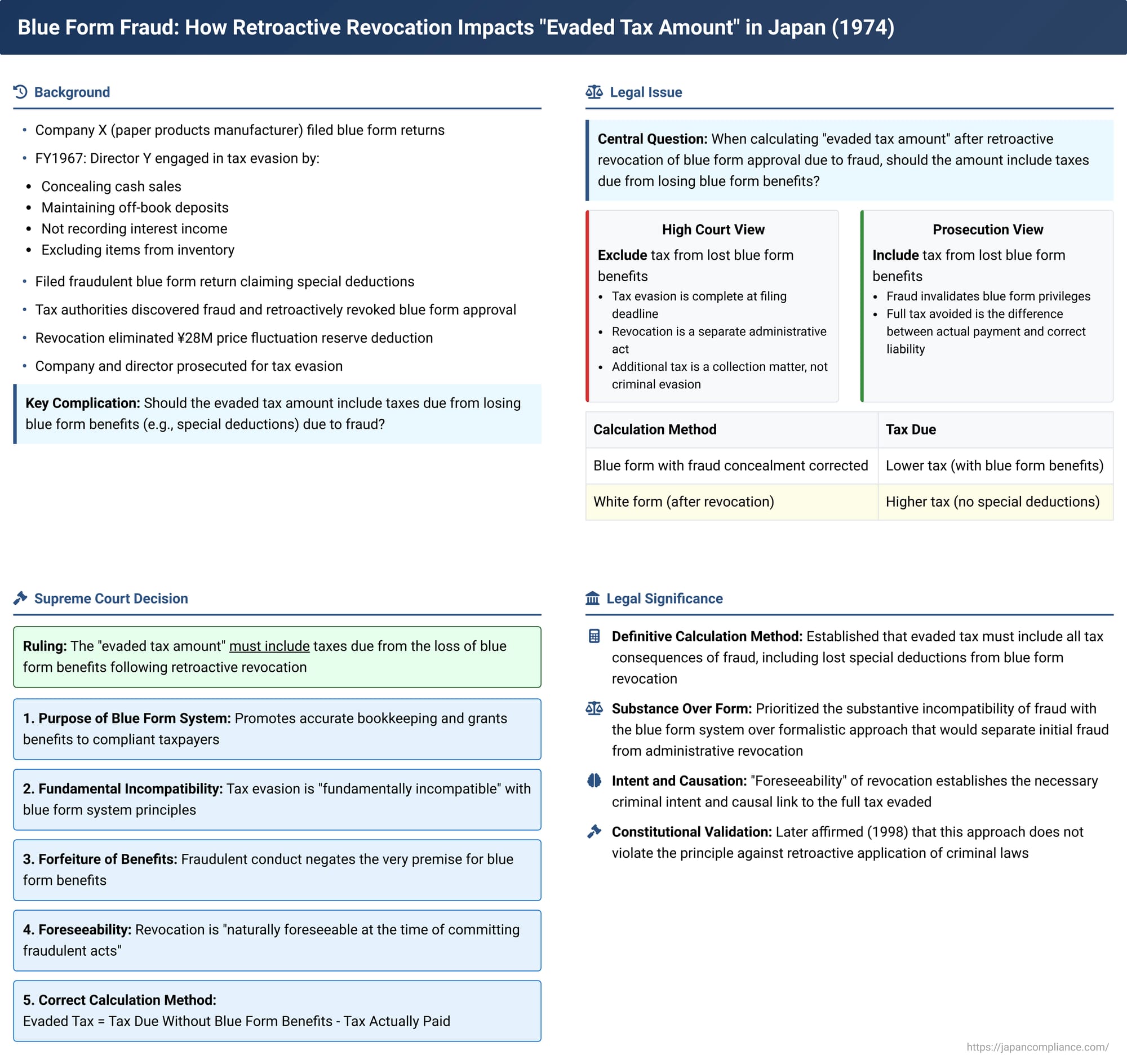

In a significant judgment on September 20, 1974, the Supreme Court of Japan clarified how the "evaded tax amount" (逋脱税額 - hodatsu zeigaku) should be calculated in criminal tax evasion cases when a company, previously approved to file "blue form" tax returns (青色申告 - aoiro shinkoku), has this approval retroactively revoked due to fraudulent activities. The Court ruled that the evaded amount must be determined as if the taxpayer was not entitled to any blue form tax benefits for the year in which the fraud occurred, effectively increasing the quantum of tax considered to have been criminally evaded.

The Evasion Scheme and the Blue Form Complication

The defendants were Company X, a manufacturer and seller of paper products, and its representative director, Y. Company X had obtained approval from the tax authorities to file its corporate tax returns using the blue form system. This system, designed to encourage proper bookkeeping, grants various tax advantages to compliant taxpayers, such as special deductions, loss carryforwards, and protection against arbitrary tax assessments.

For its fiscal year ending March 1967 (Showa 42), Company X, under the direction of Y, engaged in fraudulent acts to understate its income. These acts included deliberately omitting certain cash sales from its records, accumulating off-book bank deposits, failing to record interest earned on these off-book accounts, and improperly excluding items from its inventory. Based on these falsified books and records, Company X filed a blue form corporate tax return that significantly understated its true income and, consequently, paid only a portion of the corporate tax actually due.

Upon investigation, the tax authorities uncovered this fraudulent scheme. As a result of these findings, Company X's approval to file blue form tax returns for the fiscal year ending March 1967 was retroactively revoked. A significant consequence of this revocation was that Company X was no longer entitled to claim certain tax benefits that are exclusively available to blue form filers. In this particular case, a major benefit lost was the deduction for contributions to a price fluctuation reserve (価格変動準備金 - kakaku hendō junbikin), which amounted to approximately ¥28 million. The disallowance of this and other blue form-specific deductions meant that Company X's "correct" taxable income for that year was higher than it would have been even if only the directly concealed income was added back. This additional tax liability arising solely from the loss of blue form benefits due to the revocation is referred to as the "tax corresponding to the revocation benefit" (取消益対応税額 - torikeshi-eki taiō zeigaku).

Subsequently, Company X and its representative director Y were prosecuted for corporate tax evasion under Article 159, paragraph 1 of the Corporate Tax Act. The indictment specified the total "evaded tax amount" as ¥21,035,880. This figure included not only the tax directly evaded through the concealment of sales and other income but also the "tax corresponding to the revocation benefit"—that is, the additional tax due because the blue form benefits were no longer applicable.

The defendants argued that including this "tax corresponding to the revocation benefit" in the criminally evaded amount was improper. They contended, among other things, that this amounted to a retroactive application of penalties or a miscalculation of the actual tax evaded through their fraudulent acts, potentially conflicting with the principle of non-retroactivity of penal laws.

The first instance court (Kofu District Court) found the defendants guilty and, in doing so, included the "tax corresponding to the revocation benefit" in its calculation of the evaded tax amount. The court reasoned that Article 127, paragraph 1 of the Corporate Tax Act allows for the retroactive revocation of blue form approval in cases of fraudulent bookkeeping.

However, the Tokyo High Court, acting as the appellate court, reversed this part of the first instance judgment and remanded the case. The High Court held that the crime of tax evasion is completed when the statutory filing deadline passes with a fraudulent return having been filed. It reasoned that the amount of tax criminally evaded is fixed at that point and cannot be subsequently increased or decreased by later administrative actions, such as the revocation of blue form approval. The "tax corresponding to the revocation benefit," in the High Court's view, arose from a separate administrative act (the revocation itself) and was merely a matter for tax collection procedures, not part of the original criminal tax evasion. The prosecution then appealed the High Court's decision to the Supreme Court.

The Legal Question: What Constitutes the "Evaded Tax Amount" After Blue Form Revocation?

The central legal question before the Supreme Court was: When a corporation filing under the blue form system commits tax evasion through fraudulent acts (such as concealing income or falsifying records), and as a consequence, its blue form approval is retroactively revoked for that tax year, should the "evaded tax amount" for the purpose of the criminal charge of tax evasion include the additional tax that becomes due solely because of the loss of blue form tax benefits (like special deductions for reserves) resulting from that revocation?

In simpler terms, is the criminally evaded tax amount calculated based on:

(a) The income directly concealed, assuming the company still notionally receives its blue form benefits for that year? OR

(b) The total difference between the tax actually paid and the tax that would have been due if the company had filed honestly and had not been entitled to any blue form benefits for that fraudulent year?

The High Court had essentially adopted position (a).

The Supreme Court's Ruling: Evaded Tax Includes Loss of Blue Form Benefits

The Supreme Court overturned the Tokyo High Court's decision (which had excluded the revocation-related tax from the criminally evaded amount) and remanded the case. The Supreme Court held that the "tax corresponding to the revocation benefit" should indeed be included in the "evaded tax amount" for the purposes of the criminal charge.

The Court's reasoning was as follows:

- Purpose and Nature of the Blue Form System: The Court began by emphasizing the purpose of the blue form tax return system. It was established under the self-assessment tax regime to promote accurate bookkeeping and record-keeping by taxpayers, which are indispensable for achieving fair and proper taxation. Taxpayers who meticulously prepare and maintain their books and records in accordance with legal requirements, record all transactions faithfully, and preserve these records are granted approval to file blue form returns. This status, in turn, entitles them to various procedural and substantive tax benefits, such as protection from estimated tax assessments by the authorities and eligibility for special income calculation measures like deductions for certain reserves (e.g., price fluctuation reserves), accelerated depreciation, and the carry-forward of net operating losses.

- Fundamental Incompatibility of Tax Evasion with Blue Form Status: The Supreme Court stated that acts of tax evasion—such as a company's representative deliberately concealing cash sales, accumulating off-book deposits, failing to record off-book interest income, or excluding items from inventory to understate income, as was done by director Y for Company X—are "fundamentally incompatible" (根本的に相容れないもの - konponteki ni aiirenai mono) with the principles and objectives of the blue form tax return system.

- Forfeiture of Blue Form Benefits Due to Fraud: Consequently, if a corporation engages in such tax evasion activities for a particular fiscal year, it has, by its own fraudulent conduct, no grounds to claim or enjoy the tax benefits associated with blue form approval for that specific year's tax return. The very act of evasion negates the premise upon which blue form benefits are granted.

- Foreseeability of Blue Form Revocation: Moreover, the Court noted that it is "naturally foreseeable at the time of committing the fraudulent acts" (逋脱行為の結果として後に青色申告の承認を取り消されるであろうことは行為時において当然認識できること - hodatsu kōi no kekka toshite nochi ni aoiro shinkoku no shōnin o torikesareru dearō koto wa kōiji ni oite tōzen ninshiki dekiru koto) that such fraudulent conduct, if discovered by the tax authorities, would likely lead to the retroactive revocation of the company's blue form approval for the year in question.

- Correct Method for Calculating "Evaded Tax Amount": Based on these principles, the Supreme Court established the correct method for calculating the "evaded tax amount" in such situations: When a blue form corporation's representative commits tax evasion for a fiscal year, and the company's blue form approval for that year is subsequently revoked retroactively due to this fraud, the "evaded tax amount" for that fiscal year should be calculated as the difference between (a) the corporate tax amount that would have been due if the corporation's income had been calculated as if blue form approval had not been granted for that year (i.e., disallowing all blue form-specific tax benefits), and (b) the corporate tax amount that was actually declared and paid by the corporation based on its fraudulent return.

The Supreme Court thus found that the High Court had erred in excluding the "tax corresponding to the revocation benefit" from the criminally evaded tax amount. It noted that prior High Court precedents, which had included such amounts in the evaded tax calculations, were correct. The case was remanded for reconsideration in line with the Supreme Court's interpretation. (The judgment text notes that the remanded High Court and a subsequent Supreme Court decision ultimately found Company X and Y guilty, with Company X fined ¥6 million and Y receiving a suspended prison sentence).

Analysis and Implications

This 1974 Supreme Court decision is a leading case that definitively shaped the methodology for calculating the "evaded tax amount" in criminal tax evasion prosecutions involving blue form taxpayers whose approval is retroactively revoked:

- Definitive Stance on Calculating Evaded Tax: The ruling provides clear and authoritative guidance that the "benefit" of the blue form status (e.g., special deductions, reserve appropriations) is forfeited for any year in which the taxpayer engages in fraudulent acts justifying the retroactive revocation of that status. The tax evaded includes the tax that would have been due had these blue form benefits not been applied.

- Substance Over Form in Tax Evasion Cases: The Supreme Court prioritized the substantive incompatibility of fraudulent conduct with the blue form system over a more formalistic approach that might have separated the initial fraudulent act from the subsequent administrative act of revoking blue form approval. The Court essentially viewed the loss of blue form benefits as a direct and foreseeable consequence of the initial fraud.

- Relevance to Taxpayer's Intent and Causation: Legal commentary suggests that the "foreseeability" of the blue form revocation at the time the fraudulent acts are committed is relevant to establishing the taxpayer's criminal intent to evade the full, correctly calculated tax (including the portion related to lost blue form benefits) and the causal link between the fraudulent acts and the total amount of tax ultimately evaded.

- No Violation of Non-Retroactivity of Penal Law: While not explicitly detailed in this judgment, the Supreme Court later affirmed (in a Heisei 10 (1998) decision) that including the "tax corresponding to the revocation benefit" in the criminally evaded amount does not violate the constitutional principle against the retroactive application of criminal laws. This is because it is not about applying a new, harsher law retroactively, but rather about correctly calculating the tax due under the laws existing at the time of the offense, taking into account all the legal consequences (including the forfeiture of conditional tax benefits like blue form status) that flow from the taxpayer's fraudulent conduct.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 1974 judgment in this corporate tax evasion case provides a critical interpretation for defining the scope of the "evaded tax amount" when a blue form taxpayer's approval is retroactively revoked due to their fraudulent actions. By holding that the calculation must exclude any tax benefits specifically associated with blue form status for the year of the fraud, the Court reinforced the integrity of the blue form system. This ensures that taxpayers who fundamentally abuse the system by engaging in deceitful practices cannot simultaneously benefit from its privileges when the extent of their criminal liability for tax evasion is determined. The ruling emphasizes that the right to blue form benefits is contingent upon honest and accurate reporting, and fraudulent conduct vitiates that entitlement for the period in question.