Blowing Up a Bridge to Save It: A Japanese Supreme Court Case on the Doctrine of Necessity

Decision Date: February 4, 1960

The law recognizes that in extraordinary circumstances, a person may be forced to break one law to prevent a greater harm from occurring. This principle, known in Japanese criminal law as "Emergency Necessity" (kinkyū hinan), provides a narrow justification for otherwise illegal acts. But how imminent must a danger be to justify such an act? And how certain must it be that there are no other options?

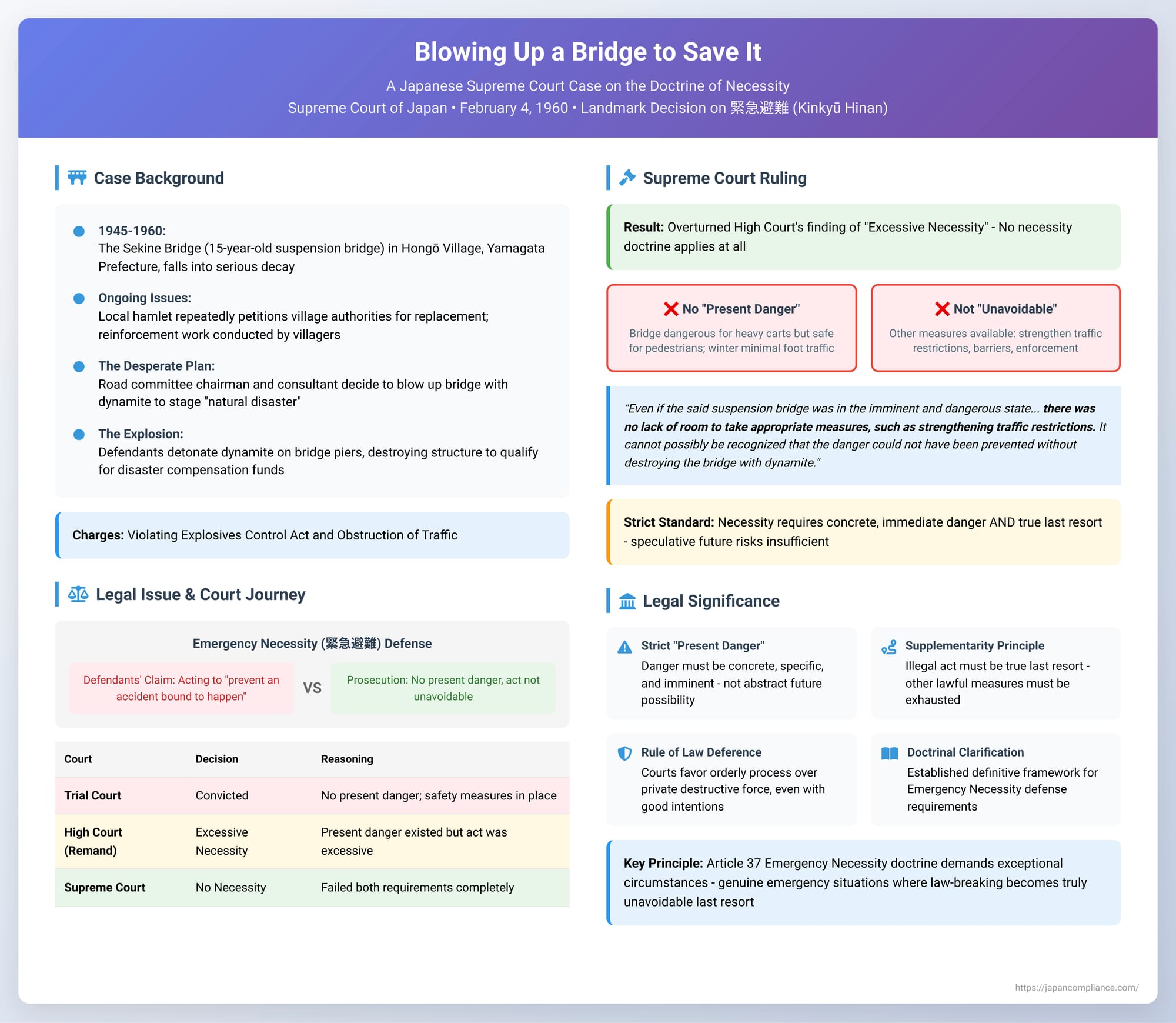

On February 4, 1960, the Supreme Court of Japan issued a landmark decision in a case that vividly illustrates the strictness of these requirements. The case involved a group of desperate villagers who, fearing their dilapidated bridge would collapse, took the drastic step of blowing it up with dynamite. Their subsequent defense of "Necessity" forced the courts to draw a clear line between a speculative future risk and a genuine "present danger," and between a truly "unavoidable" last resort and a reckless, premature act of destruction.

The Factual Background: The Perilous Sekine Bridge

The case centered on the Sekine Bridge, a 15-year-old suspension bridge in the rural village of Hongō, Yamagata Prefecture. The bridge had fallen into a state of serious decay, and local residents feared for its safety. The local hamlet had repeatedly petitioned the village authorities to replace the bridge, but no action was taken. The villagers had even conducted their own makeshift reinforcement work to keep it usable.

Frustrated by the lack of official action, the two defendants—the hamlet's road committee chairman and a consultant—devised a desperate and illicit plan. They decided to destroy the bridge with dynamite and make it appear as if it had collapsed due to heavy snow. Their hope was that by staging a "natural" disaster, they could qualify for disaster compensation funds from the government, which would finally make the construction of a new, safe bridge possible.

Following their plan, the defendants and their accomplices planted dynamite on the bridge's piers and detonated it, destroying the structure and rendering the road impassable. They were subsequently charged with violating the Explosives Control Act and with obstruction of traffic.

A Complex Legal Journey: The Lower Courts' Views

The defendants argued that their act was justified by Necessity, claiming they acted to "prevent an accident that was bound to happen." This defense led to a long and complex journey through the Japanese court system.

- The Trial Court: The first-instance court rejected the Necessity defense and convicted the defendants, sentencing them to three and a half years in prison. The court found there was no "present danger" because safety measures, such as weight limits and eventually a ban on horse-and-cart traffic, were already in place. It also reasoned that blowing up the bridge was not an "unavoidable act" to prevent danger.

- The High Court (First Ruling & Remand): The case was appealed to the Sendai High Court. In its first ruling, the High Court also convicted the defendants, but on different legal grounds related to their criminal intent. This ruling was itself appealed to the Supreme Court, which found a legal error and sent the case back to the High Court for reconsideration.

- The High Court (After Remand): A Finding of "Excessive Necessity." On rehearing the case, the High Court dramatically reversed its own prior reasoning. This time, it found that there was a "present danger," stating that the bridge's severe swaying during passage "posed a direct and imminent danger to the life and limb of passersby." It also found the act was "unavoidable" in a broad sense, reasoning that destroying the old bridge was a necessary first step in the "construction work" of building a new one.However, the High Court did not acquit the defendants. It concluded that their act was excessive. Because the bridge was the only one in the area, the defendants should have taken measures to ensure continued passage, such as building a temporary bridge, before destroying the original. By failing to do so, the harm they caused (cutting off traffic) "far exceeded the degree" of what was necessary. The court therefore found them guilty based on the doctrine of Excessive Necessity (kajō hinan), a finding that still carries criminal liability but allows for a reduced sentence.

The Supreme Court's Definitive Ruling

Unsatisfied with the finding of Excessive Necessity, the prosecution appealed to the Supreme Court. The highest court overturned the High Court's decision, finding that the situation did not meet the basic requirements for Necessity in the first place.

No "Present Danger"

The Supreme Court closely examined the evidence and disagreed with the High Court's assessment of the danger. It found that while the bridge was indeed "extremely dangerous" for heavy horse-drawn carts (which, the record showed, only used it occasionally in violation of restrictions), it was not unsafe for pedestrians. The court noted that since the demolition occurred in winter, when foot traffic was minimal, the "danger from the swaying of the said suspension bridge was not as imminent as the original instance court found." A vague, future possibility of harm was not enough to constitute a "present danger."

Not an "Unavoidable Act"

The Court then delivered the decisive part of its ruling. It held that even if one were to hypothetically assume that a present danger existed, the defendants' actions were still not justified. The Court stated:

"[E]ven if the said suspension bridge was in the imminent and dangerous state that the original instance court found, in order to prevent that danger, there was no lack of room to take appropriate measures, such as strengthening traffic restrictions. It cannot possibly be recognized that the danger could not have been prevented without destroying the bridge with dynamite as was done in this case."

Because other, less destructive options were available, the act of blowing up the bridge was not "unavoidable."

No Room for Necessity or Excessive Necessity

Since the defendants' actions failed to meet the two foundational requirements of the Necessity defense, the Court concluded that "there is no room to recognize emergency necessity, and consequently, excessive necessity also cannot be established."

A Deeper Dive: The Strict Doctrine of Kinkyū Hinan

This 1960 ruling is a masterclass in the stringent requirements of the doctrine of Necessity under Article 37 of the Japanese Penal Code. The Supreme Court's reasoning clarified two of its key pillars.

1. "Present Danger" (Genzai no Kinan)

Japanese law and legal theory have consistently held that the "presentness" of a danger required for Necessity is equivalent to the "imminence" required for self-defense. This means the danger must be concrete, specific, and close at hand. The Supreme Court's decision powerfully reinforces this strict interpretation. The abstract fear that "someone, someday, might get hurt" due to the bridge's general state of decay was insufficient. The existence of mitigating safety measures (like traffic restrictions) further reduced the danger below the threshold of legal "imminence."

2. "Unavoidable Act" (Yamu o Ezu ni Shita Kōi) and the Principle of Supplementarity

This requirement is known in legal theory as the principle of "supplementarity" (hojūsei)—the idea that the law-breaking act must be a true last resort. If any other lawful and less harmful means of averting the danger is available, the act is not "unavoidable." The Supreme Court's reasoning is a classic application of this principle. The defendants had other options: they could have more aggressively petitioned the village, worked to strengthen the enforcement of the traffic ban, or constructed barriers. Resorting to dynamite when these less destructive paths had not been exhausted meant their action was not, in the eyes of the law, unavoidable.

Because the act must be unavoidable to qualify for the Necessity defense, the High Court's finding of "Excessive Necessity" was built on a flawed premise. The doctrine of excessiveness only applies when an act is genuinely necessary but the harm caused is disproportionate. Since the Supreme Court found the act was not necessary in the first place, the question of excessiveness was moot.

Conclusion: A Strict Standard for Justifying Illegal Acts

The 1960 "Perilous Bridge" case serves as a powerful and enduring lesson on the limits of the Necessity defense in Japan. It established with clarity that the law demands a truly immediate and concrete danger, not a generalized or future risk, to justify breaking the law. Furthermore, it reinforced the principle of supplementarity with vigor, holding that an illegal act can never be deemed "unavoidable" if other lawful and less harmful avenues for resolving the danger still exist. The ruling underscores a deep judicial deference to orderly process and the rule of law, making it clear that even actions motivated by a genuine concern for public safety will not be excused if they represent a premature and disproportionate resort to private, destructive force.