Beyond the Rules: Japan's Supreme Court on 'Abuse of Dismissal Right' – The Broadcasting Company K Case (January 31, 1977)

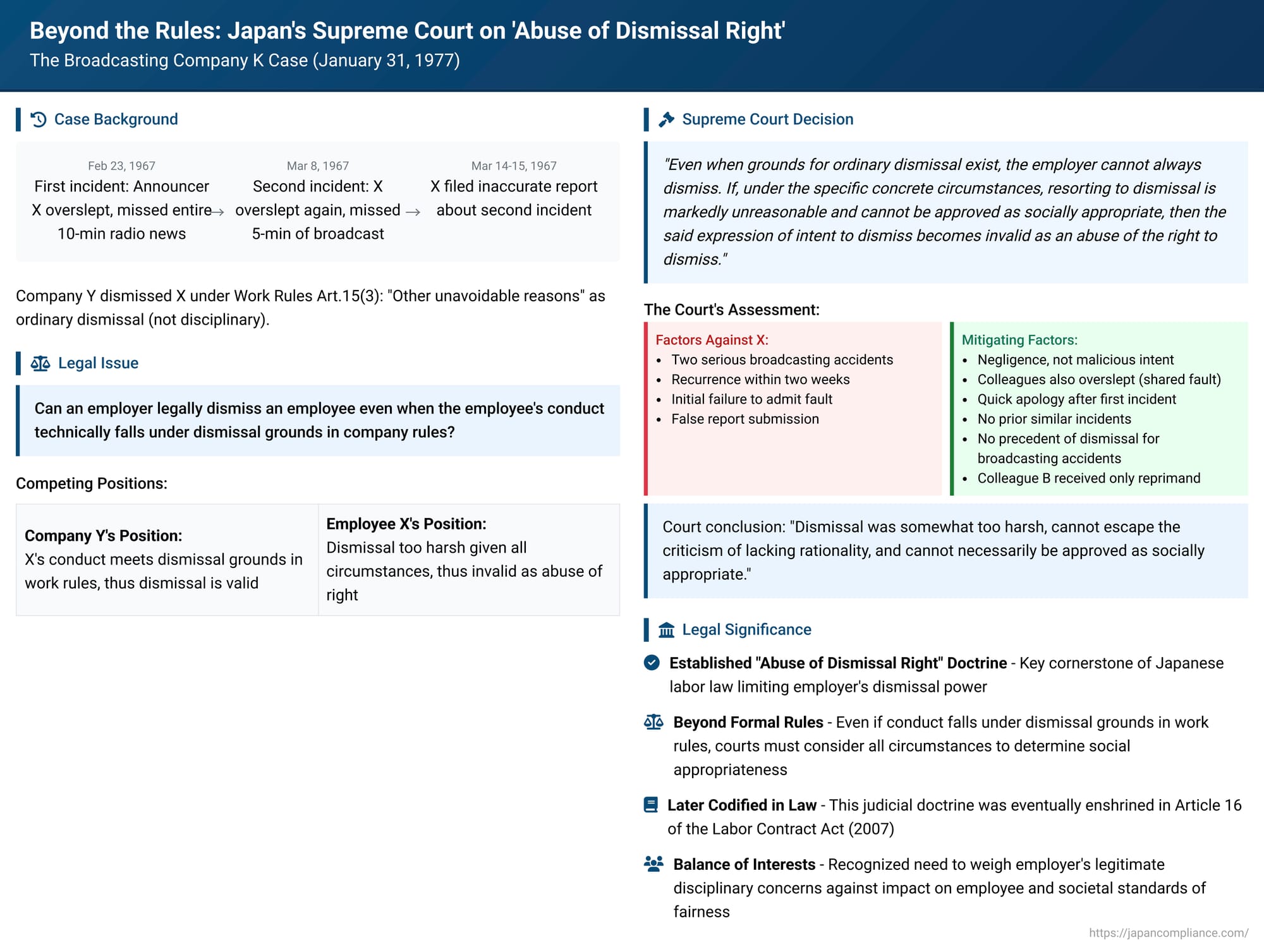

On January 31, 1977, the Second Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan delivered a judgment in a case commonly known as the "Kochi Broadcasting Case". This ruling is a cornerstone of Japanese labor law, particularly for its articulation and application of the "abuse of dismissal right" doctrine (解雇権濫用法理 - kaikoken ranyō hōri). The decision established that even if an employee's conduct technically falls under a ground for dismissal stipulated in the company's work rules, the dismissal can still be deemed invalid if, considering all circumstances, it is markedly unreasonable and not socially appropriate.

An Announcer's On-Air Mishaps

The plaintiff, X, was employed as an announcer in the news department of Defendant Company Y, a private broadcasting company. The dispute arose from two broadcasting incidents and X's subsequent conduct:

- Incident 1 (February 22-23, 1967): While on overnight duty with Colleague A (a fax operator/broadcast journalist), X overslept. As a result, a scheduled 10-minute radio news broadcast, which was due to air from 6:00 AM on February 23, was entirely missed. X reportedly did not wake up until around 6:20 AM.

- Incident 2 (March 7-8, 1967): Approximately two weeks later, X was again on overnight duty, this time with Colleague B. X overslept once more, causing the 6:00 AM radio news broadcast on March 8 to be missed for about five minutes.

- False Report and Subsequent Actions: Following the second incident, X initially failed to report the accident to superiors. When Department Head E learned of the incident around March 14 or 15 and requested an official accident report, X submitted a report that contained factual inaccuracies.

In response to these events, Company Y decided to dismiss X by way of an "ordinary dismissal" (普通解雇 - futsū kaiko), as opposed to a more severe disciplinary dismissal. Company Y's work rules (Article 15) listed grounds for ordinary dismissal, including a general clause: "3. Other unavoidable reasons comparable to the preceding items [which included inability to work due to mental/physical disability and business continuation impossibility due to disaster]". X's actions were deemed by the company to fall under this catch-all provision. The work rules also stipulated a 30-day notice period or payment of 30 days' average wages in lieu of notice for ordinary dismissals. Company Y stated that it opted for an ordinary dismissal rather than a disciplinary one out of consideration for X's future re-employment prospects.

X challenged the dismissal, asserting it was invalid and seeking confirmation of continued employment status. The Takamatsu High Court (acting as the lower appellate court in this instance) ruled in X's favor, likely finding the dismissal to be an abuse of right. Company Y then appealed this decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Seminal Formulation of the Abuse of Dismissal Right Doctrine

The Supreme Court dismissed Company Y's appeal, thereby upholding the High Court's decision that the dismissal was invalid. In doing so, it laid down a principle that has become fundamental to Japanese dismissal law:

"Even when grounds for ordinary dismissal exist, the employer cannot always dismiss. If, under the specific concrete circumstances, resorting to dismissal is markedly unreasonable and cannot be approved as socially appropriate, then the said expression of intent to dismiss becomes invalid as an abuse of the right to dismiss."

Application of the Doctrine to X's Case

The Supreme Court then meticulously applied this principle to the specific facts of X's situation, weighing the factors against X against the mitigating circumstances:

- Factors Weighing Against X (Acknowledging Misconduct):

- The two broadcasting accidents caused by X were serious, as they significantly damaged the public trust and credibility of Company Y, whose core mission was the timely delivery of broadcasts.

- The fact that X caused two similar accidents (oversleeping) within a short two-week period indicated a lack of responsibility expected of an announcer.

- X's initial failure to frankly admit fault immediately after the second incident was also noted.

- Mitigating Factors in X's Favor:

- Both broadcasting incidents stemmed from X's negligence (oversleeping) rather than any malicious intent or deliberate act.

- There was a shared responsibility for the incidents. It was customary for the fax operator on duty to wake the announcer. In both instances, the respective fax operators (Colleague A and Colleague B) had also overslept and failed to wake X or provide the news script in time. The Court found it harsh to blame X solely under these circumstances.

- X had apologized immediately after the first incident and had made efforts to get to the studio as quickly as possible after waking up during the second incident.

- The duration of the missed broadcasts (dead air time) was not excessively long in either case.

- Company Y itself had not implemented any specific measures or safeguards to ensure the flawless execution of its crucial early morning news broadcasts.

- Regarding the submission of a factually inaccurate report for the second incident, the Court considered that X might have had a misunderstanding about certain details (related to a first-floor passage door, relevant to the false explanation) and was likely feeling considerable pressure and embarrassment from having caused two broadcasting accidents in rapid succession. Therefore, this aspect could not be too heavily faulted.

- X had no prior history of broadcasting accidents, and X's general work performance record was not notably poor.

- The fax operator involved in the second incident, Colleague B, received only a reprimand (けん責 - kenseki), a much milder disciplinary action.

- There were no precedents within Company Y of an employee being dismissed for a broadcasting accident.

- X did eventually admit fault for the second incident and express an apology.

- The Court's Conclusion on the Dismissal: Weighing these competing factors, the Supreme Court concluded: "Considering these circumstances, resorting to the dismissal of X was somewhat too harsh, cannot escape the criticism of lacking rationality, and there is room to consider that it cannot necessarily be approved as socially appropriate. Therefore, the High Court's judgment, which found the dismissal notice invalid as an abuse of the right to dismiss, is ultimately affirmed as correct".

The Significance and Function of the "Abuse of Dismissal Right" Doctrine

The Kochi Broadcasting case, alongside another key ruling, the Nihon Shokuen Seizō Jiken (Japan Salt Manufacturing Case, Supreme Court, April 25, 1975), is recognized as establishing and solidifying the "abuse of dismissal right doctrine" in Japanese labor law.

- Judicial Restraint on Employer Prerogative: Under Japan's Civil Code (Article 627), employment contracts of indefinite duration can, in principle, be terminated by either party with notice, suggesting a degree of freedom in dismissal. However, particularly in the post-World War II era and during Japan's period of high economic growth, judicial precedent and academic theory developed a robust doctrine significantly limiting an employer's freedom to dismiss employees at will.

- Balancing Stability and Fairness: This doctrine, often invoking general legal principles against the abuse of rights, effectively posited that a dismissal, even if formally permissible under work rules or general contract law, would be deemed void if it lacked "objectively reasonable grounds" and was not "socially appropriate" when all circumstances were considered. This judicially created norm provided a crucial measure of employment security and reflected the then-prevalent practices of long-term employment, especially in larger Japanese enterprises.

- Integration with Work Rules: The Kochi Broadcasting judgment specifically addressed how this doctrine applies when an employer has established work rules that stipulate grounds for dismissal. The Supreme Court clarified that even if an employee's conduct technically falls under a prescribed dismissal cause, the dismissal's validity is still subject to the overarching "abuse of right" test. The employer cannot simply point to a rule violation; the dismissal must also be a fair and reasonable response in the given situation.

- Nuance in Judicial Assessment: The Supreme Court's carefully worded conclusion in this case – using phrases like "somewhat too harsh," "cannot escape the criticism of lacking rationality," and "room to consider that it cannot necessarily be approved as socially appropriate" – was seen by commentators as reflecting a sophisticated judicial balancing act, weighing the employer's legitimate concerns against the impact on the employee and societal standards of fairness.

Evolution and the Future of Dismissal Jurisprudence in Japan

The employment landscape in Japan has undergone considerable transformation since the Kochi Broadcasting judgment in 1977.

- Legislative Developments: Anti-discrimination laws affecting dismissals have become more extensive. Crucially, the abuse of dismissal right doctrine, originally a product of case law, was formally codified into statutory law in 2007 with the enactment of Article 16 of the Labor Contract Act. This article states: "If a dismissal lacks objectively reasonable grounds and is not considered to be appropriate in general societal terms, it is treated as an abuse of rights and is void."

- Changing Employment Practices: Traditional norms such as lifetime employment, widespread internal training, and unified hiring of new graduates are no longer as dominant as they once were. Labor market policies have increasingly focused on flexibility and the activation of the external labor market.

- Adapting the Doctrine: In this evolving context, while respecting the foundational principles laid down by the Supreme Court in cases like Kochi Broadcasting, new interpretive approaches are continually being sought for Labor Contract Act Article 16. Courts have demonstrated a willingness to differentiate the application of the doctrine based on the nature of the employment relationship. For instance, dismissals for lack of ability might be viewed differently for employees hired for specific, high-level skills versus new graduates hired under traditional systems предполагающие extensive internal development. The criteria for judging the fairness of restructuring dismissals (整理解雇 - seiri kaiko) have also been significantly refined over time through the well-known "four factors" test.

- Shifting Emphasis: The commentary suggests a potential shift away from a heavy reliance on "mitigating circumstances" (情状酌量 - jōjō shakuryō) that were often assessed within the context of Japan's traditionally dense and long-term workplace relationships. Instead, future interpretations may place greater emphasis on a rational interpretation of the dismissal grounds themselves, while also considering modern workplace values such as teamwork and employee contribution, and aligning with broader labor market policies that emphasize dynamic adjustment and efficient allocation of labor.

Conclusion: A Lasting Legacy of Fairness in Dismissals

The Supreme Court's 1977 judgment in the Broadcasting Company K (Kochi Broadcasting) case remains a landmark in Japanese labor law. It powerfully articulated and applied the "abuse of dismissal right" doctrine, establishing that an employer's power to dismiss employees is not absolute, even when formal grounds for dismissal under work rules appear to be met. The decision mandates a holistic assessment of whether a dismissal is "markedly unreasonable" and "not socially appropriate" in light of all specific circumstances. This principle, now enshrined in the Labor Contract Act, continues to serve as a crucial safeguard for employees against arbitrary or disproportionately harsh dismissals, ensuring that decisions to terminate employment are grounded in both objective reason and societal fairness. While the socio-economic context of employment in Japan continues to evolve, the fundamental quest for balance and fairness championed by this ruling endures.