Beyond the Principal: Liability of Media and Endorsers in Misleading Advertising in Japan

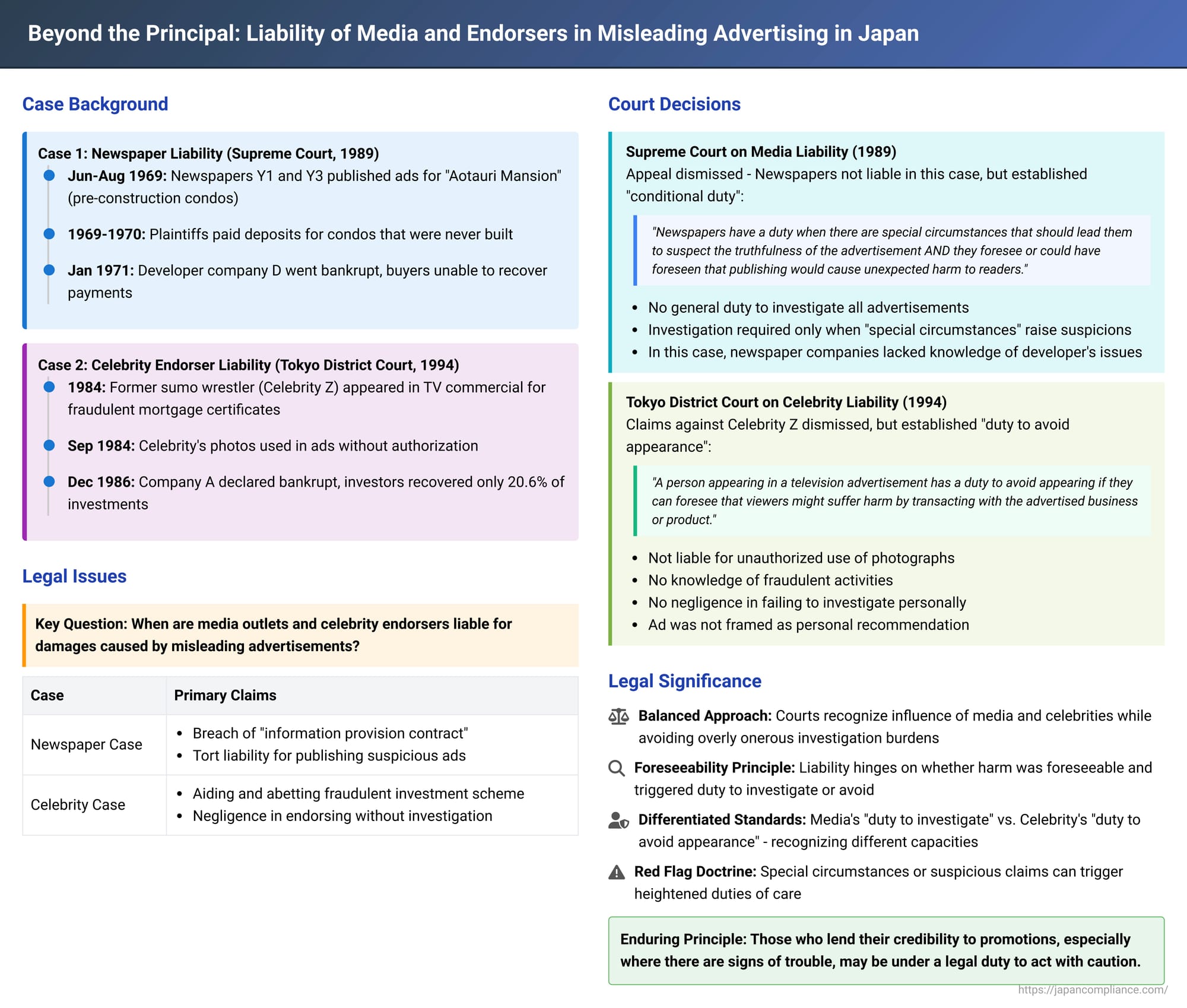

When consumers suffer losses due to misleading or fraudulent advertising, the primary advertiser often bears direct responsibility. However, Japanese courts have also examined the potential liability of other parties involved in disseminating these advertisements, such as newspaper publishers, advertising agencies, and celebrity endorsers. Two key court decisions shed light on the circumstances under which these intermediaries might be held accountable.

Case 1: The Newspaper's Conditional Duty – Supreme Court, September 19, 1989

This case (Supreme Court, Third Petty Bench, Heisei 1 (O) No. 1129) addressed the responsibility of newspaper companies and advertising agencies for publishing advertisements for pre-construction condominiums that ultimately were never built, leading to financial losses for buyers.

Judgment Date: September 19, 1989

The Factual Landscape: The "Aotauri Mansion" Debacle

- The Advertisement: In June and August 1969, two prominent newspaper companies, Newspaper Y1 (formerly B1 Newspaper Company in court documents) and Newspaper Y3 (formerly B3 Newspaper Company), published advertisements for pre-construction condominiums ("Aotauri Mansion" or "blue-sky sale" condos) to be built by Company D (D Corpo Co. Ltd.). These ads were brokered and prepared by Ad Agency Y2 (formerly B2 Advertising Company) and Ad Agency Y4 (formerly B4 Advertising Company) respectively. The ads clearly identified Company D as the advertiser, providing its name, address, and phone number.

- The Plaintiffs' Loss: Plaintiffs, Mr. X1 and Mr. X2, saw these advertisements and subsequently entered into contracts with Company D to purchase units in the "E" condominium complex, which was scheduled for completion in May 1970. Mr. X1 paid a total of ¥4.26 million, and Mr. X2 paid ¥1 million as down payments. However, the "E" condominiums were never constructed. Company D went bankrupt on January 20, 1971, and the plaintiffs were unable to take possession of their units or recover their payments.

- The Advertiser's Background: Company D was part of the "H Group," a conglomerate controlled by an individual known as J. From around 1967, authorities including the Tokyo Metropolitan Government, the Metropolitan Police Department, and the Ministry of Finance (now Ministry of Finance) suspected the H Group's operations of violating the Law Concerning the Regulation of Receiving of Capital Subscription, Deposits and Interest on Deposits (the "Investment Law"). These suspicions became more concrete after April 1970. In May 1970, directors of an H Group company were arrested, and the Tokyo Metropolitan Government initiated an on-site investigation into Company D for suspected violations of the Real Estate Brokerage Act, bringing the scandal to public attention. Subsequently, Company D filed for composition proceedings in August 1970, and its real estate license was revoked by the Tokyo Metropolitan Government that same month.

- Delayed Public Disclosure: The Tokyo Metropolitan Government was aware that many buyers had already paid for H Group condominiums by April 1970. Fearing that premature public disclosure of the group's issues would trigger a run on the companies and jeopardize buyers' ability to recover their funds, the authorities deliberately refrained from publicizing the concerns until the on-site investigation in May 1970. Consequently, reporters from the defendant newspaper companies only began actively investigating the H Group after the police actions and on-site investigations were widely reported from May 28, 1970. The newspapers and ad agencies asserted they had no information about the H Group's troubles before this public disclosure.

The Plaintiffs' Claims and Lower Court Rulings

The plaintiffs sued the newspaper companies and advertising agencies, arguing:

- A breach of an "information provision contract" allegedly existing between a newspaper and its subscribers, obligating the newspaper to provide accurate information and to investigate and confirm the content of advertisements, which they failed to do.

- Tort liability, asserting that the defendants had a duty to refuse to publish, or at least qualify, advertisements for projects that were unlikely to be realized, and their failure to do so was unlawful.

Both the Tokyo District Court (judgment May 29, 1978) and the Tokyo High Court (judgment May 31, 1984) dismissed the plaintiffs' claims. The plaintiffs then appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Judgment

The Supreme Court dismissed the plaintiffs' appeal. Its reasoning established a nuanced standard for media liability:

- No General Duty to Investigate All Ads: The Court stated that, generally, newspaper companies do not have a broad legal obligation to thoroughly investigate and confirm the truthfulness of all advertisements before publication. Newspaper ads are essentially one source of information, and there's no inevitable link between a reader seeing an ad and entering into the advertised transaction, particularly for significant purchases like real estate.

- A Conditional Duty of Care: However, the Court recognized the significant influence of newspaper advertisements and the trust readers place in them, which is not entirely separate from the trust in the newspaper's news reporting capabilities. Therefore, newspapers (as advertising media) and ad agencies (as intermediaries) do have a duty in certain situations. This duty arises when:

- There are "special circumstances" that should lead them to suspect the truthfulness of the advertisement's content, AND

- They foresaw, or could have foreseen, that publishing the ad could cause unexpected harm to readers.

In such cases, they have an obligation to investigate and confirm the ad's veracity and must not provide false advertising to readers. This duty exists to protect the trust readers place in newspaper advertisements.

- Application to the Facts: The Supreme Court found that at the time Newspaper Y1, Newspaper Y3, Ad Agency Y2, and Ad Agency Y4 published or handled the advertisements (June-August 1969), they could not be said to have encountered such "special circumstances" or the necessary "foreseeability of harm." While authorities harbored suspicions about Company D's operations, these were not made public until May 1970 due to concerns about causing a panic among existing creditors. Thus, the defendants were not deemed negligent for failing to conduct a truthfulness investigation at the time of publication.

The Supreme Court focused its analysis on tort liability, which is considered more appropriate than contract liability, as the impact of misleading advertising is not limited to newspaper subscribers. While the causal link between seeing an ad and making a purchase can be debated, the significant influence of advertisements in major newspapers generally supports acknowledging causation, shifting the legal analysis to questions of illegality and negligence.

This ruling established a conditional duty for media outlets. While not requiring them to vet every advertisement rigorously, it mandates investigation if specific red flags and foreseeable harm are present. A later Osaka District Court decision in 2010 applied this principle to find a newspaper liable for publishing a deceptive recruitment advertisement for "pachinko hitters," deeming the offer ("no expenses, funds provided, minimum ¥50,000 daily for playing pachinko nearby") so implausible as to constitute "special circumstances" warranting suspicion.

Case 2: The Celebrity Endorser's Burden – Tokyo District Court, July 25, 1994

This case (Tokyo District Court, Case No. Showa 62 (Wa) No. 13720) explored the liability of a celebrity who appeared in advertisements for a fraudulent investment scheme.

Judgment Date: July 25, 1994

The Factual Landscape: The Fraudulent Mortgage Certificate Scheme

- The Scheme: From around 1984, Company A, managed by Y1, solicited investments from the general public for "mortgage certificates." These were, in reality, part of a fraudulent "multiple sale" operation where the total value of certificates sold exceeded the value of the underlying mortgage bonds. Advertisements, including newspaper inserts and company pamphlets, deceptively described these investments as "safe" and "reliable."

- The Celebrity Endorser: Celebrity Z (referred to as Y3 in court documents), a popular former sumo wrestler who had reached the rank of Ozeki in 1981 and even released a music record in 1982 before retiring in 1985, was involved in Company A's advertising.

- Celebrity Z's Involvement:

- Around June 1984, Y1 commissioned Producer B to create a television commercial for Company A. Producer B decided to feature Celebrity Z. Ad Agency D was brought in to manage the television broadcast contracts.

- Celebrity Z agreed to appear in the commercial but was reportedly not given detailed explanations of Company A's business operations and did not conduct his own investigation.

- Ad Agency D commissioned a credit report on Company A, which indicated potential but also financial weaknesses and concerns about Y1's management skills. This report was not shared with Celebrity Z. Producer B only learned of it after the commercial was filmed.

- The commercial was filmed on August 26, 1984. Celebrity Z stated he merely followed directions and had no input into the content. During the shoot, Y1 took still photographs of Celebrity Z, which Z claimed he was unaware of.

- Contracts were formalized on September 1, 1984, between Company A and C Company (Celebrity Z's record label, for ad production) and between C Company and Celebrity Z (delegating ad appearance matters to C Company).

- Red Flags and Unauthorized Use:

- In late August/early September 1984, Ad Agency D informed Producer B about the negative credit report. D Agency also consulted a newspaper ad review association, which rated Company A as "D-rank" (indicating serious business problems and unsuitability for advertising) due to illegal operations (failure to register under the Investment Law) and suspicious mortgage acquisition methods.

- Producer B conveyed this D-rank status to Y1 and advised canceling the commercial contract, but Y1 merely promised to try to improve Company A's rating. The commercial film was delivered to Company A on September 21, 1984.

- While the D-rank should have made television broadcast virtually impossible through major channels, about 160 of the plaintiffs claimed to have seen the commercial, suggesting it might have aired on smaller stations. The court acknowledged it couldn't definitively rule out that the commercial was broadcast.

- Company A also used the unauthorized still photographs of Celebrity Z taken by Y1 in newspaper insert advertisements and company brochures. In December 1984, Producer B noticed Celebrity Z's photo in a magazine ad and protested to Y1. Celebrity Z also protested to Y1 via C Company.

- The Outcome for Investors: Company A was declared bankrupt on December 23, 1986 (Y1 reportedly fled to the United States). The plaintiffs, who had invested in the scheme, were only able to recover about 20.6% of their investments through bankruptcy dividends. They sued Y1, other Company A officers (Y2s), and Celebrity Z (as an aider and abettor to the tort).

The Tokyo District Court's Judgment on Celebrity Z

The Tokyo District Court found Y1 and two of the Company A officers liable. However, it dismissed the claims against eleven other officers (deemed nominal directors) and, crucially, against Celebrity Z. The court's reasoning for absolving Celebrity Z was as follows:

- Unauthorized Use of Still Photographs: Celebrity Z was not liable for the use of his still photographs in newspaper ads and brochures because he had not consented to their use, and their unauthorized use was not foreseeable by him.

- Appearance in the Television Commercial:

- No Intent to Aid Fraud: The court found no evidence that Celebrity Z had knowledge of Company A's fraudulent activities. He had not received detailed explanations about the business, nor was he aware of the negative credit report or the D-rank evaluation.

- No Negligence: This was the core of the court's analysis regarding the TV commercial.

- General Duty of Celebrity Endorsers: The court acknowledged that television advertising has a broad, extensive, and non-specific viewership and can significantly influence purchasing motivations. Given this, a person appearing in such an advertisement, particularly one intended for television broadcast, has a duty to avoid appearing if they can foresee that viewers, relying on the endorser's fame, career, etc., might suffer harm by transacting with the advertised business or product.

- Scope of Foreseeability and Avoidance Duty: The extent of this duty of foresight and avoidance should be determined on a case-by-case basis, considering factors such as the type of business of the advertiser, the type of product/service being advertised, the content of the advertisement, the endorser's fame and background, the degree of autonomy the endorser could exercise in the ad creation process, and the amount of compensation the endorser received.

- Application to Celebrity Z: In this specific instance, the court found it "difficult to say" that Celebrity Z should have foreseen the risk of customers suffering damages by dealing with Company A by personally investigating whether there were any illegalities in Company A's mortgage certificate sales. Therefore, the court did not find Celebrity Z negligent for his appearance in the commercial.

The court in this case emphasized a "duty to avoid appearance" if risk is foreseeable, which differs slightly from the "duty to investigate" highlighted for media in the Supreme Court case. This may reflect a recognition of the potentially limited investigative capacities of individual celebrity endorsers compared to media organizations.

A key factor in the court's decision regarding Celebrity Z appears to be that the television commercial was not framed as a personal recommendation from him based on his own beliefs or experiences regarding Company A or its mortgage certificates. This contrasts with an earlier Osaka District Court case (1987) where an actor who provided a personal recommendation in a brochure for a fraudulent land sale scheme (a "genya shōhō" or wasteland sales scam) was found liable for negligence because he failed to investigate the claims he was personally endorsing. Some critics argue that sharply distinguishing between personal and impersonal endorsements might absolve most celebrity endorsers from liability, as few ads explicitly state a personal belief. An alternative view is that a personal endorsement should perhaps heighten the duty to investigate.

Key Principles and Enduring Questions

These two cases highlight several important principles regarding the liability of intermediaries in advertising:

- Foreseeability of Harm: This is a central theme. For both media outlets and celebrity endorsers, a crucial factor in determining liability is whether they could or should have foreseen that their involvement in the advertisement could lead to consumer harm.

- Triggering Conditions for Duty:

- For media, "special circumstances raising suspicion about the ad's truthfulness" can trigger a duty to investigate.

- For celebrity endorsers, the foreseeability of consumers relying on their fame and potentially suffering harm can trigger a "duty to avoid appearance." The nature of the endorsement (e.g., a direct personal recommendation versus a more generic appearance) might also influence the perceived scope of this duty, though this distinction is debated.

- Acknowledging Influence: Both court decisions recognize the substantial impact that newspaper advertisements and celebrity endorsements can have on consumer behavior and trust.

- Balancing Consumer Protection and Practical Burdens: The courts attempt to strike a balance between protecting consumers from deceptive practices and not imposing overly onerous or impractical investigative burdens on all parties involved in the advertising ecosystem.

While these judgments provide some framework, the responsibilities of those involved in advertising continue to be an area of legal discussion, especially with the rise of new advertising platforms like social media, where influencers and platform providers also play significant roles in disseminating commercial messages. The core principle remains: those who lend their credibility or platform to promotions, especially where there are signs of trouble or a high potential for consumer reliance leading to harm, may find themselves under a legal duty to act with caution and care.