Deconstructing Japan's Journey Towards Gender Equality in the Workplace

TL;DR

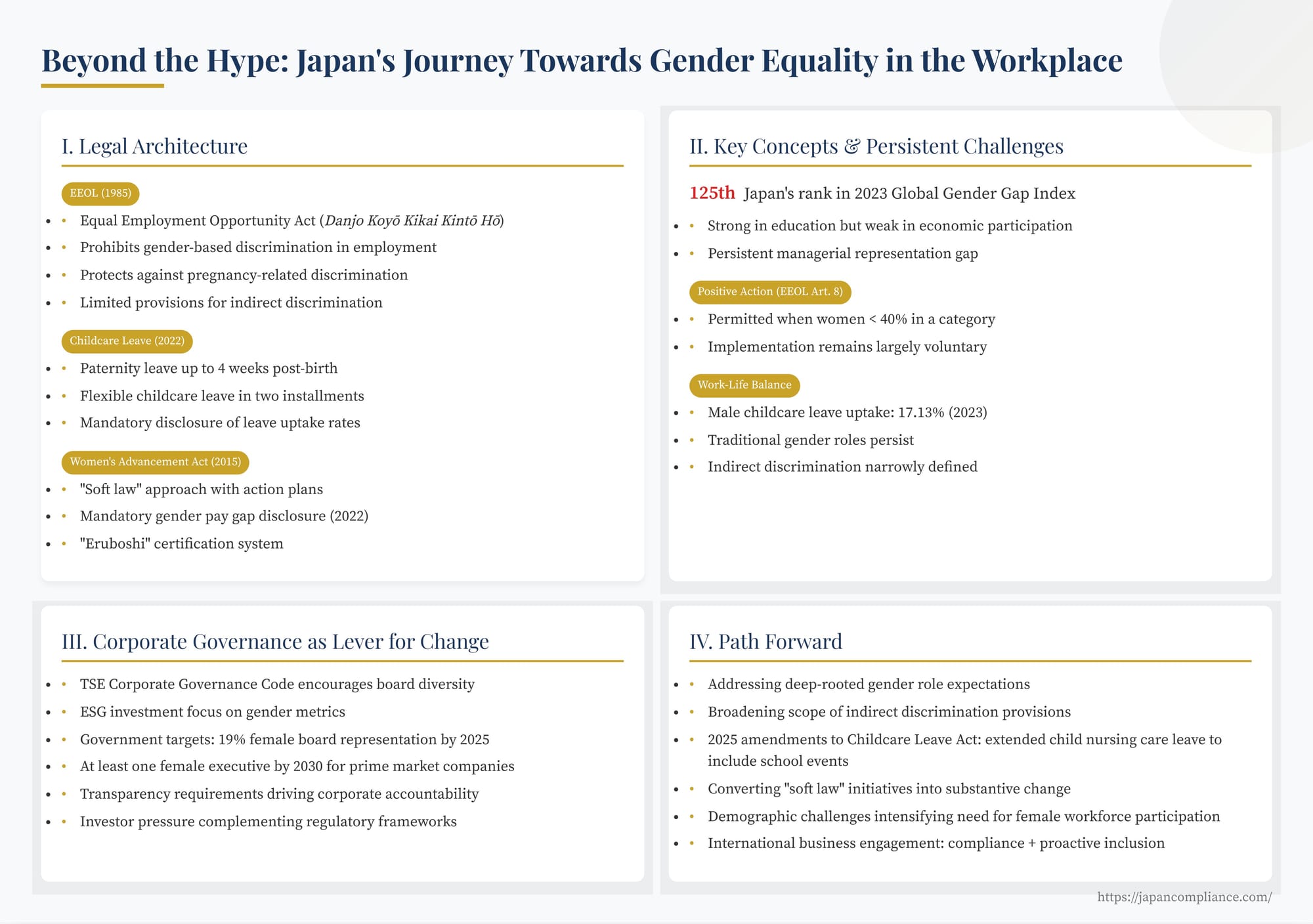

Japan’s gender-equality drive rests on three pillars: the Equal Employment Opportunity Act, the Childcare & Family Care Leave Act, and the Women’s Advancement Act. Reforms since 2022 toughen anti-discrimination rules, expand parental-leave rights—especially for men—and force large firms to publish gender-pay gaps. Yet narrow definitions of indirect discrimination, deep-rooted work-style norms and low female representation in management still hamper progress.

Table of Contents

- The Legal Architecture for Equality

- EEOL – Foundation & Remaining Gaps

- Childcare & Family-Care Leave – Work–Life Balance Reforms

- Women’s Advancement Act – “Soft-Law” Transparency

- Key Concepts & Persistent Challenges

- Corporate Governance as a Diversity Lever

- The Path Forward for Companies & Investors

Japan, a global economic powerhouse, has been on a multi-decade journey to address gender inequality in its workforce. While traditional images of Japanese workplaces often evoke long working hours and a male-dominated corporate culture, a series of legislative efforts and societal shifts are gradually reshaping this landscape. For international businesses operating in or engaging with Japan, understanding the nuances of this evolution is not just a matter of compliance but a strategic imperative for talent acquisition, retention, and fostering an inclusive corporate environment.

This article delves into the core legislative pillars underpinning Japan's push for gender equality, examines the practical challenges and ongoing debates, and provides insights into what these developments mean for the future of work in the country.

The Legal Architecture for Equality: A Multi-Pillar Approach

Japan's framework for promoting gender equality in employment rests on several key pieces of legislation, each addressing different facets of the issue, from direct discrimination to work-life balance and proactive measures for women's advancement.

1. The Equal Employment Opportunity Act (EEOL): The Foundation Stone

Enacted in 1985 and significantly revised multiple times, the Danjo Koyō Kikai Kintō Hō (男女雇用機会均等法), or Equal Employment Opportunity Act (EEOL), laid the initial groundwork for combating gender-based discrimination in the workplace.

- Evolution and Core Principles: The EEOL marked a pivotal shift from a legal framework that often treated men and women differently (under the guise of protection) to one that, at its core, advocates for equal treatment. Initially, some of its provisions were "effort obligations" (doryoku gimu), but subsequent amendments have strengthened these into direct prohibitions. The law now broadly prohibits discrimination based on gender in recruitment, hiring, assignments, promotions, training, benefits, retirement, and dismissal.

- Pregnancy-Related Discrimination: A critical aspect of the EEOL is its handling of pregnancy and childbirth-related discrimination. The law has evolved to recognize that treating women unfavorably due to pregnancy or childbirth constitutes discrimination. This includes measures like prohibiting disadvantageous treatment related to maternity leave. The focus is on "balanced treatment" (kinkō toriatsukai), acknowledging the unique aspects of pregnancy and childbirth while ensuring women are not penalized in their careers.

- Indirect Discrimination (Kansetsu Sabetsu): A Cautious Approach: The concept of indirect discrimination – where seemingly neutral policies or practices disproportionately disadvantage one gender – was formally introduced into the EEOL in a 2007 revision. However, its application remains narrowly defined, limited to specific criteria related to height, weight, or physical strength requirements for recruitment or hiring, rules requiring nationwide transferability for promotion, and certain types of job transfers that could disproportionately affect women due to family responsibilities. The rationale for this limited scope often cites the need for legal clarity and stability. This cautious approach means that many practices which might be considered indirectly discriminatory in other jurisdictions may not fall under the current strict definition in Japan, posing a challenge for a more comprehensive eradication of gender-based disadvantages.

- Challenges in Efficacy: Despite the EEOL's prohibitions, achieving substantive equality has been an ongoing struggle. Some critics argue that the listed nature of prohibited discriminatory acts can sometimes hinder the law's effectiveness if a particular discriminatory practice doesn't neatly fit into the enumerated categories. Furthermore, exceptions to discrimination, while sometimes necessary for specific occupational requirements, have historically been addressed more through administrative interpretations than explicit legal provisions, leading to occasional ambiguities.

2. The Childcare and Family Care Leave Act: Supporting Work-Life Balance

Recognizing that true equality requires support for employees with family responsibilities, the Ikuji Kaigo Kyūgyō Hō (育児介護休業法), or Childcare and Family Care Leave Act, has become a cornerstone of Japan's work-life balance policies. This Act has undergone significant revisions, particularly in recent years, aimed at encouraging more equitable sharing of parental duties.

- Recent Reforms (Post-2022): Key amendments, rolled out in stages from April 2022, have focused on enhancing leave options, especially for male employees. These include:

- "Male Paternity Leave" (Sangō Papa Ikukyū or Shusshōji Ikuji Kyūgyō): A new system allowing fathers to take up to four weeks of leave within the first eight weeks after a child's birth, which can be taken flexibly in two installments.

- Flexible Use of Regular Childcare Leave: Both parents can now split their regular childcare leave (generally until the child turns one, extendable under certain conditions) into two installments, offering greater flexibility in how they manage work and childcare.

- Employer Obligations for Creating a Conducive Environment: Companies are now mandated to inform employees about their leave entitlements, proactively ask about their intentions to take leave, and implement measures to create a workplace environment where it is easier for employees to take leave. For larger companies (initially those with over 1,000 employees, with scope expanding), public disclosure of their employees' childcare leave uptake rates became mandatory from April 2023.

- Relaxed Eligibility for Fixed-Term Employees: The requirement for fixed-term contract workers to have been employed for at least one year to be eligible for childcare leave was abolished, broadening access.

- The "Right to Return to Original Position": A Key Tenet? A significant discussion point surrounding childcare leave is the concept of an employee's right to return to their pre-leave position or a substantially similar one. While the law and accompanying guidelines urge employers to make such considerations (gen-shoku fukki gensoku), it's not always a legally guaranteed right in the strictest sense, especially if it clashes with an employer's broad discretion in personnel transfers common in many Japanese companies. Disadvantageous treatment related to taking leave is prohibited, but reassignments without pay cuts have, in some court cases, not been deemed disadvantageous. This remains an area of ongoing focus as ensuring career continuity post-leave is vital for retaining female talent and encouraging male participation in childcare.

3. Act on Promotion of Women's Participation and Advancement in the Workplace (Women's Advancement Act): A "Soft Law" Catalyst

Enacted in 2015 and subsequently amended, the Josei Katsuyaku Suishin Hō (女性活躍推進法), or Women's Advancement Act, takes a different, "soft law" approach. Instead of mandating specific outcomes or imposing direct penalties for inaction (beyond disclosure requirements), it aims to foster voluntary efforts by companies to promote female participation and career progression.

- Core Mechanisms:

- Mandatory Action Plans: Companies above a certain size (currently those with 101 or more employees) are required to:

- Analyze their own situation regarding female employees (e.g., percentage of women in recruitment, average tenure by gender, working hours, proportion of women in managerial roles).

- Set voluntary, measurable targets based on this analysis.

- Develop and publish an action plan outlining the measures they will take to achieve these targets.

- Regularly disclose data on their progress.

- Information Disclosure: A crucial element is the mandatory public disclosure of information. Initially focused on action plans and self-set targets, this was expanded. As of July 2022, for companies with 301 or more employees, disclosure of the gender pay gap became mandatory. This transparency is intended to create external pressure and allow stakeholders (including potential employees and investors) to assess a company's commitment.

- Mandatory Action Plans: Companies above a certain size (currently those with 101 or more employees) are required to:

- "Eruboshi" and "Platinum Eruboshi" Certification: The Act includes a certification system ("Eruboshi" meaning "L-Star," signifying Leading, Lady, Labour) that recognizes companies making excellent progress in promoting women. Higher levels of certification ("Platinum Eruboshi") offer benefits like preferential treatment in public procurement bids and can enhance corporate image.

- Shifting Mindsets: The Act encourages companies to move beyond simply preventing discrimination to proactively creating environments where women can thrive. It pushes businesses to examine their own working styles and corporate cultures, recognizing that systemic changes are often needed to support women's careers effectively. The hope is that this approach will encourage a shift from a "single-earner (male) model" to a "dual-earner model" of employment.

Key Concepts and Persistent Challenges

While the legislative framework is in place, several underlying concepts and persistent societal challenges continue to shape Japan's progress towards gender equality.

The Gender Gap Index: A Sobering Reality

Japan consistently ranks low among developed nations in the World Economic Forum's Global Gender Gap Report. For example, in 2023, Japan was 125th out of 146 countries, and in 2024, it stood at 118th. While Japan scores highly in education and health, its rankings in economic participation and opportunity, and particularly political empowerment, remain significantly low. This highlights the substantial work still needed to translate legal frameworks into tangible, widespread equality. The low representation of women in managerial positions and the persistent gender wage gap are major contributing factors to the low economic score.

The Nuance of "Positive Action"

The EEOL (Article 8) permits "positive action" – measures specifically aimed at proactively improving the situation for women where they are substantially underrepresented (defined as women constituting less than 40% in a particular employment category). This allows companies to, for instance, preferentially hire or promote qualified women, or offer women-only training for leadership roles, without these actions being considered reverse discrimination against men. The Women's Advancement Act further encourages such proactive steps through its action plan framework. However, the implementation of positive action remains largely voluntary, and its effectiveness depends on individual corporate commitment and a genuine desire to change existing imbalances rather than merely fulfilling quotas.

Work-Life Balance: An Enduring Pursuit

Despite legislative enhancements like the revised Childcare and Family Care Leave Act, achieving a genuine work-life balance remains a significant challenge for many in Japan, particularly women who still bear a disproportionate share of household and childcare responsibilities. Long working hours, though gradually being addressed through work style reforms, can make it difficult for both men and women to combine careers with family life. While male uptake of childcare leave is slowly increasing (reaching 17.13% for private-sector employees in the fiscal year ending March 2023), it still lags far behind that of women, indicating that traditional gender roles continue to influence workplace and family dynamics. The 2025 amendments to the Childcare and Family Care Leave Act aim to further expand support, for example, by extending the reasons for taking "child nursing care leave" to include school events and making the leave available for children up to the third grade of elementary school, and broadening the scope of overtime work exemptions for parents of young children.

Indirect Discrimination: A Limited Net

As mentioned, the scope of legally recognized indirect discrimination in Japan is narrow. This means that certain recruitment or promotion criteria, such as requirements for specific career tracks that have historically been male-dominated or transferability requirements that are harder for women with care responsibilities to meet, may not be challenged as illegal indirect discrimination unless they fall into the few explicitly defined categories. This limited definition can leave systemic barriers unaddressed, making it harder to achieve true equality of outcome. Broader recognition and more robust mechanisms to identify and rectify indirect discrimination are considered by many experts as necessary next steps.

Corporate Governance: A New Lever for Change?

The push for gender diversity is also increasingly visible in the realm of corporate governance. The Tokyo Stock Exchange's Corporate Governance Code encourages diversity on boards, including female representation. The Women's Advancement Act's disclosure requirements concerning the percentage of women in executive and managerial roles also align with this trend. Investors, both domestic and international, are paying more attention to environmental, social, and governance (ESG) factors, with gender diversity being a key social metric. This growing focus from the investment community adds another layer of impetus for companies to take gender equality more seriously, not just as a legal or HR issue, but as a component of good governance and sustainable business practice. The government’s target for prime market listed companies to have 19% female board representation by 2025 and at least one female executive by 2030 further signals this direction.

The Path Forward

Japan's journey toward gender equality in the workplace is a complex interplay of legal reforms, evolving corporate practices, and slowly changing societal norms. The EEOL provides the foundational anti-discrimination measures, the Childcare and Family Care Leave Act aims to facilitate work-life integration, and the Women's Advancement Act seeks to catalyze proactive corporate change through transparency and goal-setting.

However, significant challenges remain. The deeply ingrained gender roles, the limited scope of indirect discrimination provisions, the actual uptake and impact of work-life balance measures, and the translation of "soft law" initiatives into widespread, substantive change are all areas requiring ongoing attention.

For U.S. businesses, navigating this landscape requires a nuanced understanding of both the letter of the law and the cultural context. It involves not only ensuring compliance with anti-discrimination and leave provisions but also proactively fostering an inclusive environment that genuinely supports the career advancement of all employees, irrespective of gender. As Japan continues to grapple with demographic changes and the need to fully utilize its entire talent pool, the imperative for greater gender equality will only intensify, making it a key factor in the country's future economic and social development.

- Platform Workers in Japan: A Landmark Ruling and Its Implications for the Gig Economy

- Strengthening Governance in Japan: Key Takeaways from the Revised CGS Guidelines

- Protecting Innovation: Key Intellectual Property Strategies for Startups in Japan

- Equal Employment Opportunity between Men and Women Act – MHLW

- Childcare & Family Care Leave Act Overview – MHLW

- Act on Promotion of Women’s Participation and Advancement – Cabinet Office