Beyond the Diagnosis: A 1978 Japanese Supreme Court Ruling on Criminal Responsibility

Decision Date: March 24, 1978

A core tenet of modern criminal justice is that a person should only be punished if they are truly responsible for their actions. This principle leads to one of the most difficult questions in law: how should the legal system treat those who commit crimes while suffering from a severe mental disorder? In Japan, this question is governed by Article 39 of the Penal Code, which provides for acquittal in cases of "lack of mental capacity" (shinshin sōshitsu) and mitigation of punishment for "diminished mental capacity" (shinshin kōjaku).

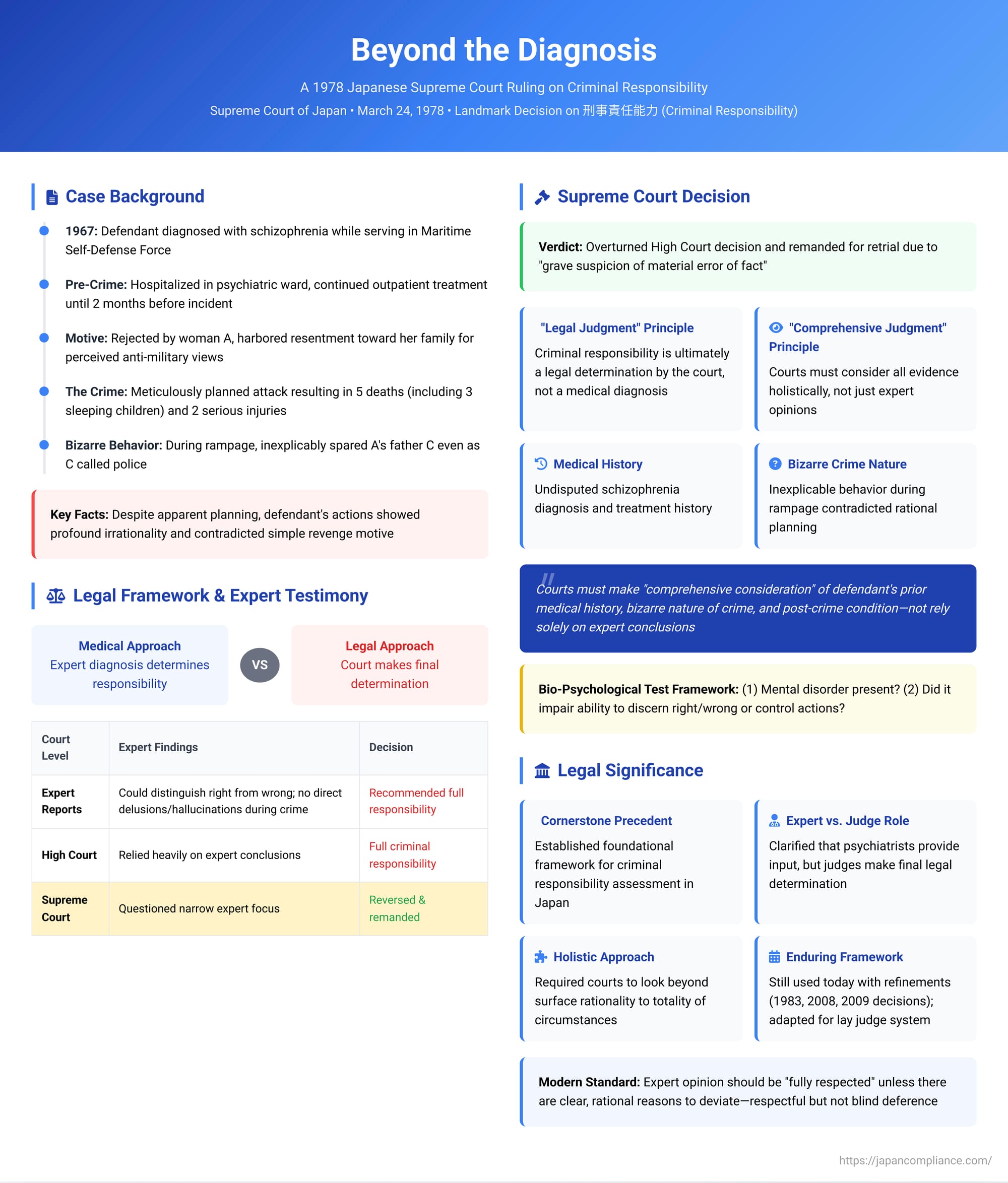

But who makes this ultimate determination? Is it a purely medical diagnosis left to psychiatric experts, or is it a legal judgment for the courts? On March 24, 1978, the Supreme Court of Japan issued a landmark decision in a case involving a horrific mass killing committed by a man with schizophrenia. In its ruling, the Court established a powerful and enduring framework, declaring that the ultimate assessment of criminal responsibility is a "legal judgment" for the court, which must be based on a "comprehensive" evaluation of all evidence and cannot be delegated to expert opinion alone.

The Factual Background: A Bizarre and Tragic Rampage

The case involved a defendant with a documented history of severe mental illness. While serving in the Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force in 1967, he was diagnosed with schizophrenia. He was subsequently hospitalized in a psychiatric ward and, after his discharge, continued to receive outpatient treatment until about two months before the crime.

The Supposed Motive:

The lower court identified what appeared to be a motive for the defendant's subsequent rampage. He had been rejected by a woman, A, with whom he had no concrete relationship, and he harbored resentment towards her and her family for what he perceived as their anti-military views.

The Crime:

This supposed grudge culminated in a horrific outburst of violence. The defendant committed a meticulously planned attack that resulted in the deaths of five people and the serious injury of two others. After taking a taxi driver hostage, he went to the home of A's family and, using an iron bar, bludgeoned the occupants, including three young, sleeping children. He also attacked and killed two neighbors who rushed to the scene upon hearing the commotion.

The Inexplicable Behavior:

Despite the apparent planning, the defendant's actions during the rampage were marked by profoundly bizarre and inexplicable behavior that seemed to contradict a simple motive of revenge. For instance, while in the midst of the attack, he did nothing to harm A's father, C, even as C tended to the wounded taxi driver and then left the house, right in front of the defendant, to go call the police from a local substation. This and other strange actions suggested a mind not operating on a purely rational level.

The Battle of the Experts and the Lower Courts' Decision

During the trial, the court heard from two different psychiatric experts. Both experts concluded that, at the moment of the crime, the defendant was not acting under the direct command of schizophrenic delusions or hallucinations. They both opined that he was in a state where he could distinguish right from wrong.

However, both psychiatric reports also confirmed several crucial facts:

- The defendant was, at the time of the crime, in a "defective state" of hebephrenic schizophrenia, characterized by personality deterioration and emotional blunting.

- This type of schizophrenia has a poor prognosis, and periods of remission are often temporary, leading to progressive mental decline.

- One of the experts (Dr. M) explicitly stated that schizophrenic delusions did likely play a role in the formation of the defendant's motive. He also affirmed that the defendant's strange behavior during the trial was a genuine symptom of his illness, not malingering.

Despite these findings, the High Court, relying heavily on the experts' conclusion that the defendant could discern right from wrong and emphasizing the planned nature of the attack, found that the defendant had full criminal responsibility for his actions.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Intervention

The Supreme Court took a different view. In a rare move, it overturned the High Court's decision and sent the case back for retrial, finding a "grave suspicion of a material error of fact" regarding the defendant's mental capacity.

The Court's reasoning established two foundational principles for how courts must assess criminal responsibility.

1. The "Legal Judgment" Principle:

The Supreme Court implicitly declared that the ultimate determination of whether a defendant meets the legal criteria for insanity or diminished capacity is a legal judgment, not a medical one. While psychiatric expert testimony is essential evidence, the court is not bound by the expert's ultimate conclusion. The judge is the final arbiter of legal responsibility.

2. The "Comprehensive Judgment" Principle:

The Court faulted the lower court for its narrow focus. It held that a proper assessment of criminal responsibility requires a "comprehensive consideration" of all relevant evidence, not just the expert's opinion or the seemingly rational aspects of the crime. The Court explicitly listed the factors that should have been weighed more heavily:

- The Defendant's Prior Medical History: His undisputed diagnosis of schizophrenia and history of hospitalization and treatment.

- The Bizarre Nature of the Crime: The inexplicable and irrational aspects of the defendant's conduct during the rampage, which could not be explained by the supposed motive alone.

- The Defendant's Post-Crime Condition: The symptoms of schizophrenia that were still observable during the trial.

By failing to properly weigh these factors against the expert's conclusion, the High Court had abdicated its duty to make an independent and comprehensive legal judgment. Based on a holistic view of the evidence, the Supreme Court concluded that there was a strong suspicion that the defendant's capacity to control his actions was, in fact, "markedly diminished" due to the influence of his schizophrenia.

The Enduring Framework for Assessing Criminal Responsibility

This 1978 ruling is a cornerstone of modern Japanese criminal law. It operationalized the long-standing "bio-psychological test" for criminal responsibility, which asks two questions: (1) Does the defendant have a mental disorder (the biological element)? and (2) Did this disorder deprive them of the ability to discern right from wrong or the ability to control their actions based on that discernment (the psychological element)?

The decision clarified that while psychiatrists provide essential input on the biological element and its effects, it is the court's exclusive role to make the final legal determination on the psychological element and its legal significance.

This framework has been consistently upheld and refined in subsequent decades. A 1983 Supreme Court decision explicitly affirmed that the "biological and psychological elements... are ultimately subject to the court's evaluation." More recently, a 2008 decision added the nuance that expert opinion should be "fully respected" unless there are clear, rational reasons to deviate from it, establishing a standard of respectful, but not blind, deference. The system has also been adapted for Japan's modern quasi-jury system (saiban-in seido), with a 2009 decision suggesting that courts consider the "degree of connection between the defendant's original personality and the commission of the crime" as a way to make the analysis more accessible to lay citizen judges.

Conclusion: A Judge's Duty to Look Beyond the Diagnosis

The 1978 Supreme Court decision stands as a powerful statement on the distinct roles of law and medicine in the courtroom. It empowers and, more importantly, obligates judges to be the final arbiters of criminal responsibility. By mandating a "comprehensive" approach, it requires courts to look beyond the expert's diagnosis and the surface-level rationality of a crime, and to instead consider the totality of the defendant's history, the nature of their illness, and the often-irrational reality of their actions. In overturning a conviction that relied too heavily on an expert's narrow conclusion, the Supreme Court ensured that the ultimate question of legal responsibility in Japan would remain a matter of law, justice, and a holistic understanding of the human being before the court.