Post-Employment Non-Competes in Japan: Legal Tests & Drafting Tips

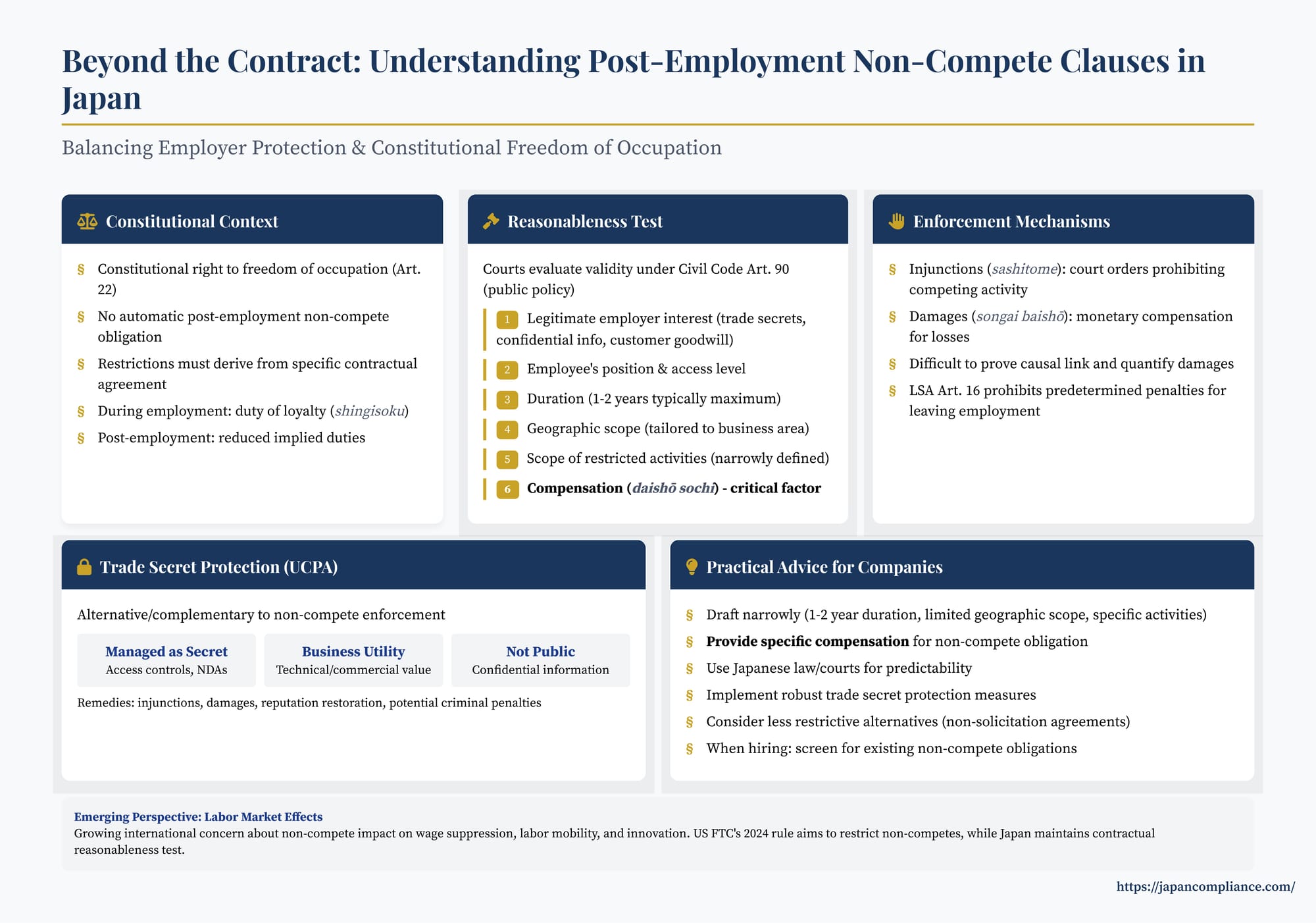

TL;DR: Japanese courts allow post-employment non-competes only when narrowly tailored, backed by real protectable interests, limited in time/area/scope, and—critically—paired with specific compensation. Over-broad or unpaid clauses fail under the Civil Code’s public-policy test.

Table of Contents

- Freedom of Occupation vs. Contractual Restrictions

- The Reasonableness Test: Balancing Interests

- Enforcement: Injunctions and Damages

- Beyond Non-Competes: Trade Secret Protection (UCPA)

- Emerging Perspectives: Non-Competes and Market Competition

- Practical Advice for US Companies Operating in Japan

- Conclusion: A Balancing Act Requiring Care

In the global competition for talent and market share, companies often seek to protect their investments in employees, customer relationships, and confidential information through post-employment non-compete agreements. These clauses, restricting a former employee's ability to work for competitors or start competing businesses for a certain period after leaving, are common tools worldwide. However, their enforceability varies significantly across jurisdictions, reflecting different balances struck between employer interests and individual freedoms.

Japan presents a unique landscape for non-competes (kyōgyō hishi gimu keiyaku or tokuyaku - 競業避止義務契約・特約). While not prohibited outright, Japanese courts subject these agreements to rigorous scrutiny, carefully weighing the employer's need for protection against the employee's fundamental right to choose their occupation, guaranteed by Article 22 of the Constitution. For US companies operating in Japan, understanding the specific factors Japanese courts consider when assessing the validity and enforceability of non-compete clauses is crucial for both protecting legitimate business interests and avoiding disputes when hiring or parting ways with employees.

Freedom of Occupation vs. Contractual Restrictions

The starting point in Japanese law is the constitutional guarantee of freedom of occupation. This implies a fundamental right for individuals to choose their work and pursue their careers, including the freedom to change jobs (tenshoku no jiyū).

- During Employment: While employed, workers generally owe a duty of loyalty and good faith (shingisoku - 信義則) to their employer under the labor contract. This duty typically implies an obligation not to engage in activities directly harmful to the employer's business, such as working simultaneously for a direct competitor or misappropriating confidential information.

- Post-Employment: Once the employment relationship ends, however, this implied duty significantly diminishes. Japanese law does not automatically impose a post-employment non-compete obligation. Therefore, any restriction on a former employee's ability to compete must stem from a specific contractual agreement – the non-compete clause. These clauses are often included in initial employment agreements, separate non-compete agreements (sometimes signed upon promotion or receiving specific training), or retirement agreements. They may also appear in company work rules (shūgyō kisoku - 就業規則), which can form part of the employment contract under certain conditions (Labor Contract Act, Arts. 7, 10).

The Reasonableness Test: Balancing Interests

Because post-employment non-competes directly restrict the constitutionally protected freedom of occupation, Japanese courts evaluate their validity under the general principle of public policy and good morals (Civil Code, Art. 90). A non-compete clause will be deemed void and unenforceable if it imposes unreasonable restrictions on the former employee.

Over time, courts have developed a multi-factor balancing test to determine reasonableness. While not a rigid checklist, the analysis typically revolves around the following key considerations:

1. Legitimate Employer Interest (Protectable Interest):

- Is there a specific, legitimate business interest that the employer needs to protect through the non-compete? This interest must go beyond merely shielding the company from ordinary competition.

- Protectable interests typically include:

- Trade Secrets: Information meeting the definition under the Unfair Competition Prevention Act (UCPA) – kept secret, useful for business, not publicly known.

- Confidential Information: Information that may not strictly qualify as a trade secret but is highly sensitive, proprietary, and valuable (e.g., detailed customer lists developed through significant effort, unique internal know-how).

- Customer Goodwill: Specific relationships with clients nurtured through the employer's investment, where the departing employee could unfairly leverage these connections.

- The employer must demonstrate the existence of such an interest and that the specific employee had access to it.

2. Employee's Position and Access:

- Was the employee's role and level of access such that they genuinely acquired and could potentially misuse the protected interest to the employer's significant detriment?

- Restrictions are more likely to be upheld for senior executives, key researchers, or sales staff with deep client relationships and access to highly confidential strategic information, compared to lower-level employees with limited access.

3. Duration of the Restriction:

- Is the non-compete period reasonably necessary to protect the employer's interest?

- Japanese courts are generally skeptical of long non-compete durations. While there's no absolute limit, restrictions exceeding one to two years often face heightened scrutiny and require strong justification.

- The reasonableness of the duration depends on the nature of the protected interest. For example, rapidly evolving technical know-how might only justify a shorter period, whereas customer relationships might warrant a slightly longer one (though still typically within the 1-2 year range). Indefinite or overly long restrictions are almost always deemed unreasonable.

4. Geographic Scope:

- Is the territorial scope of the restriction reasonably tailored to the area where the employer conducts business and where the employee's competition would actually harm the employer?

- Nationwide bans are often considered overly broad unless the employer has a truly national business presence and the employee's activities could impact that entire market. Restrictions should ideally be limited to specific prefectures or regions where competition is relevant.

5. Scope of Restricted Activities:

- Does the clause narrowly define the types of businesses, roles, or activities the employee is prohibited from engaging in?

- Restrictions must be limited to activities that directly compete with the employer's business and relate to the protectable interest. Overly broad clauses preventing the employee from working in an entire industry, or in any capacity (even non-competing roles) for a competitor, are likely unreasonable.

6. Compensation / Consideration (Daishō Sochi - 代償措置):

- This is a particularly critical factor in Japanese jurisprudence. Was the employee provided with specific, adequate compensation in direct exchange for accepting the post-employment non-compete obligation?

- Unlike some other jurisdictions where continued employment might suffice as consideration, Japanese courts place significant weight on whether separate, identifiable compensation was paid for the non-compete restriction itself. This could be a lump sum payment upon signing, specific additions to salary during employment explicitly designated as consideration for the non-compete, or a distinct payment upon retirement tied to the obligation.

- Lack of clear and adequate compensation is a major reason why non-competes are often found unenforceable in Japan. While formally just one factor in the overall reasonableness assessment, its absence makes it very difficult for an employer to justify the restriction.

- Standard salary or regular retirement allowances (taishokukin) are generally not considered sufficient compensation for a non-compete unless a specific portion is clearly designated and justified as such. The compensation must be seen as genuinely offsetting the burden imposed on the employee's freedom of occupation.

Courts weigh all these factors holistically. A restriction might be reasonable in duration and scope, but if no specific compensation was provided, it could still be deemed void under public policy. Conversely, substantial compensation might help justify a slightly broader restriction, although it cannot salvage a fundamentally unreasonable clause (e.g., one protecting no legitimate interest or lasting indefinitely).

Enforcement: Injunctions and Damages

If a non-compete clause is deemed valid and the former employee breaches it, the employer has potential remedies:

- Injunctions (Sashitome): The employer can petition the court for an order prohibiting the former employee from continuing the competing activity. This is often sought through preliminary injunction proceedings (kari-shobun) for faster relief. Some lower court cases have debated whether the employer must demonstrate actual or imminent harm resulting from the breach, or if simply proving the breach of a valid clause is sufficient for an injunction. Clarity on this point is still evolving.

- Damages (Songai Baishō): The employer can sue for monetary damages caused by the breach, typically lost profits. However, proving the causal link between the employee's competition and the employer's specific losses, and quantifying those losses accurately, can be notoriously difficult.

- No Penalties for Leaving: It's important to note that the Labor Standards Act (Art. 16) prohibits contracts that pre-determine penalties or liquidated damages for breach of the employment contract itself (which includes leaving employment). While damages for breaching a valid post-employment non-compete are theoretically possible, clauses imposing a fixed penalty simply for leaving the company or joining a competitor (regardless of actual harm) are generally unenforceable under LSA Art. 16.

Beyond Non-Competes: Trade Secret Protection (UCPA)

Even if a non-compete agreement is invalid, unenforceable, or simply non-existent, former employees are not free to misuse confidential company information. Japan's Unfair Competition Prevention Act (UCPA) (Fusei Kyōsō Bōshi Hō - 不正競争防止法) provides robust protection for trade secrets (eigyō himitsu - 営業秘密).

To qualify for UCPA protection, information must meet three criteria:

- Managed as secret (e.g., through access controls, confidentiality markings, NDAs).

- Useful for business operations (technical or commercial information).

- Not publicly known.

Former employees who improperly acquire, use, or disclose their former employer's trade secrets can be subject to:

- Injunctions: Court orders to stop the use or disclosure.

- Damages: Including potentially lost profits (with statutory provisions that can assist in calculating damages).

- Measures to Restore Business Reputation.

- Criminal Penalties in cases of malicious intent for unfair gain or causing harm.

Therefore, maintaining strong internal controls to identify and protect genuine trade secrets, coupled with clear confidentiality clauses in employment agreements, offers a crucial layer of protection independent of non-compete enforceability.

Emerging Perspectives: Non-Competes and Market Competition

Internationally, and increasingly in Japan, there is a growing recognition that non-compete clauses have implications beyond the individual employment relationship. Concerns are being raised about their potential impact on broader labor market competition:

- Wage Suppression: Widespread use of non-competes may reduce employee bargaining power and suppress overall wage growth by limiting outside options.

- Reduced Mobility: They can hinder the efficient allocation of talent by preventing workers from moving to roles where they might be more productive or better compensated.

- Innovation and Entrepreneurship: Non-competes can stifle innovation by preventing experienced employees from joining or founding competing startups, potentially locking valuable knowledge within established firms.

This perspective is reflected in the aggressive stance taken by the US Federal Trade Commission (FTC), which finalized a rule in 2024 aiming for a near-total ban on most employee non-competes, citing their detrimental effects on competition (though legal challenges are ongoing). While Japan's JFTC has also expressed interest in the impact of non-competes on labor markets, the primary legal framework in Japan currently remains the contractual reasonableness test under public policy, rather than a competition law-based prohibition. However, this broader economic perspective may influence future policy discussions or judicial sensitivity towards overly restrictive clauses.

Practical Advice for US Companies Operating in Japan

For US-based companies employing individuals in Japan, navigating non-compete issues requires careful consideration of Japanese legal standards:

- Draft Narrowly: If using non-competes, tailor them narrowly. Define the protectable interest clearly. Limit duration (1 year is safer, 2 years requires strong justification), geographic scope (avoid nationwide bans unless essential), and restricted activities (focus only on truly competing roles/functions).

- Provide Specific Compensation: This is arguably the most critical step for enforceability in Japan. Clearly document that a specific payment (lump sum, dedicated periodic payment) is being provided as consideration for the non-compete obligation, separate from regular salary or standard retirement benefits. Ensure the amount is reasonably adequate given the scope and duration of the restriction.

- Use Japanese Law/Courts: While choice of law clauses might select US law, Japanese courts will likely apply Japanese public policy (Civil Code Art. 90) as mandatory rules when assessing the reasonableness of restrictions affecting employment in Japan. Specifying Japanese law and Japanese courts can provide more predictability.

- Emphasize Confidentiality and Trade Secrets: Implement robust measures to protect confidential information and trade secrets under the UCPA, including clear policies, training, access controls, and well-drafted confidentiality clauses in employment agreements. This provides protection even if the non-compete fails.

- Consider Alternatives: Depending on the role and risks, explore less restrictive alternatives like non-solicitation agreements (focused on clients or employees, though also subject to reasonableness checks), extended notice periods (garden leave is less common/enforceable in Japan), or relying solely on confidentiality and trade secret protections.

- Hiring Practices: When hiring from competitors in Japan, inquire about existing non-compete obligations and assess the associated risks. Avoid inducing breaches of valid agreements.

Conclusion: A Balancing Act Requiring Care

Post-employment non-compete agreements occupy a sensitive space in Japanese employment law, balancing the employer's need to protect legitimate investments and confidential information against the individual's fundamental right to pursue their chosen career. Unlike the more varied landscape in the United States (pre-FTC rule), Japanese courts apply a relatively consistent multi-factor reasonableness test grounded in public policy.

Enforceability hinges on demonstrating a specific protectable interest and ensuring the restrictions on the former employee are narrowly tailored in duration, geography, and scope. Critically, the provision of clear, adequate, and specific compensation for the non-compete obligation is often a decisive factor in Japanese courts.

For international companies, directly transplanting US-style non-compete agreements is unlikely to be effective. A successful approach requires careful drafting aligned with Japanese judicial standards, a strong emphasis on providing specific consideration, and potentially prioritizing robust confidentiality and trade secret protection strategies as a more reliable foundation for safeguarding critical business interests in Japan's dynamic labor market.

- Engaging Japan’s Freelance Workforce: The New Freelance Protection Act

- Mind the Gap: Wage Disparity Between Fixed-Term and Indefinite-Term Employees

- When Accidents Happen: Workers' Compensation for Non-Traditional Employees in Japan

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare — Q&A on Post-Employment Restrictions

https://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/seisakunitsuite/bunya/roudouhourei/koyou_kisei/faq.html