Beyond the Clock-In: Japan's Mitsubishi Shipyard Case Defines "Working Hours"

The definition of "working hours" is a cornerstone of labor law, fundamentally impacting wage calculations (especially overtime pay), rest period entitlements, and overall compliance with statutory limits on work. In Japan, the Labor Standards Act (LSA) sets maximum working hours but does not explicitly define what constitutes "working hours." This ambiguity has led to considerable legal interpretation, particularly concerning activities that employees perform before or after their main tasks, such as changing into uniforms or preparing tools. The Supreme Court of Japan's decision in the Mitsubishi Heavy Industries Nagasaki Shipyard case on March 9, 2000, provided a landmark clarification, establishing an objective standard for determining what time counts as working hours under the LSA.

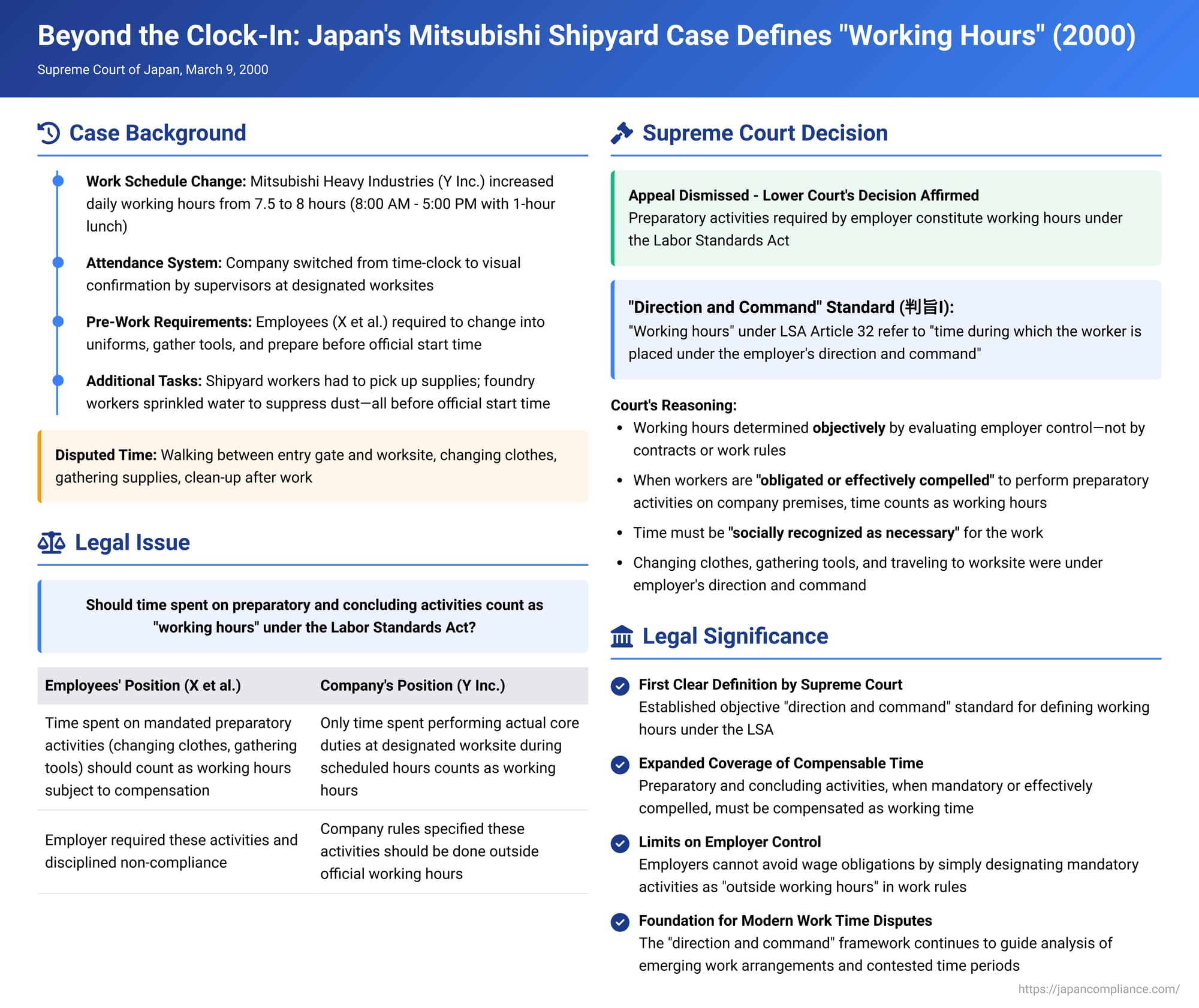

The Mitsubishi Shipyard Scenario: Uniforms, Tools, and Unpaid Time

The case involved Y Inc. (Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, Ltd.), a major shipbuilding and machinery manufacturing company, and its employees, X et al., at the N Shipyard. Following the introduction of a full five-day work week, Y Inc. adjusted its daily actual working time from 7.5 hours to 8 hours. The company's work rules stipulated official start and end times (8:00 AM to 5:00 PM, with a one-hour lunch break from 12:00 PM to 1:00 PM). A significant change was the method of tracking attendance: Y Inc. moved from a time-clock system to one where supervisors visually confirmed employees' presence at their designated worksites at the start and end of the shift.

Company policy dictated that actual work was to commence precisely at the official start time at the employee's worksite. Activities such as changing into work clothes and donning safety protection gear were to be completed before this official start time. Similarly, changing out of work clothes and other post-work routines were to be performed after the official end time.

These pre-work activities were not merely suggestions. Failure to wear the required work clothes and safety gear could lead to disciplinary action, refusal of permission to work, or a negative impact on performance evaluations, which in turn could affect wages. Specific groups of employees had additional mandated pre-start tasks:

- Shipyard construction workers were required by Y Inc. to pick up auxiliary materials and consumable supplies from storage areas before the official morning and afternoon start times.

- Foundry workers were required by their superiors to sprinkle water several times a month before the morning start time to suppress dust.

X et al. argued that the time spent on these and other related activities should be considered "working hours" under the LSA, for which they were entitled to (overtime) compensation. The disputed activities included:

- Walking time from the shipyard entry gate, via the changing rooms, to their respective worksites, and the return journey.

- Time spent in the changing rooms donning and doffing work clothes, safety gear, and tools.

- Time for personal clean-up after work, such as washing hands, face, or bathing.

- Time spent on the mandated pre-start activities like picking up supplies and sprinkling water.

The Nagasaki District Court and the Fukuoka High Court partially agreed with the employees. They found that the time spent donning work clothes and safety gear and then moving from the changing rooms to the preparatory exercise area, the time for pre-start supply pick-up and water sprinkling, and the time after the official end of work for moving from the worksite to changing rooms and doffing work clothes and gear, did constitute LSA working hours. Y Inc. appealed the High Court's decision regarding the parts it lost.

The Supreme Court's 2000 Definition of "Working Hours"

The Supreme Court dismissed Y Inc.'s appeal, upholding the core findings of the lower courts regarding the compensability of these preparatory and finishing times. In doing so, it laid out a clear definition and framework for determining LSA working hours:

- The "Direction and Command" Standard (判旨I):

The Court definitively stated that "working hours" under Article 32 of the LSA refer to "time during which the worker is placed under the employer's direction and command" (使用者の指揮命令下に置かれている時間 - shiki meirei ka ni okareteiru jikan).

Whether a particular period of time qualifies as LSA working hours is to be determined objectively by evaluating if the worker's actions can be assessed as being under the employer's direction and command. Crucially, this determination is not to be decided by the stipulations of labor contracts, work rules, or collective labor agreements. This established the "objective theory," specifically the "direction and command theory," as the prevailing standard, ensuring that LSA protections could not be easily contracted out. - Preparatory and Finishing Activities as Working Hours (判旨II):

The Court further elaborated on how this standard applies to activities performed before or after core tasks: "When a worker is obligated by the employer, or is effectively compelled (余儀なくされた - yoginaku sareta), to perform preparatory activities for their assigned duties, etc., within the business premises, even if these activities are designated under the rules to be performed outside of scheduled working hours, such activities, barring special circumstances, are to be evaluated as being under the employer's direction and command. The time spent on such activities, as long as it is socially recognized as necessary for the work, constitutes LSA working hours." - Application to the Mitsubishi Case (判旨III):

Applying these principles, the Supreme Court found:The Supreme Court affirmed the High Court's judgment that the time X et al. spent on these specific activities was "socially recognized as necessary" and thus constituted LSA working hours.- Y Inc. had obligated its employees, X et al., to wear specific work clothes and safety/protective gear to perform their actual work. It also required that the donning and doffing of this gear take place at designated changing rooms or rest areas within the shipyard premises. Therefore, the Court concluded that the time spent donning this gear and the subsequent travel from the changing rooms to the preparatory exercise area (where applicable) could be objectively evaluated as being under Y Inc.'s direction and command.

- Similarly, the mandated pre-start tasks of picking up supplies and, for foundry workers, sprinkling water, were also activities conducted under Y Inc.'s direction and command.

- Furthermore, the Court held that even after the completion of their "actual work" at the scheduled end time, the employees remained under Y Inc.'s direction and command until they had finished doffing their work clothes and protective gear at the designated changing facilities.

Understanding the "Direction and Command" Standard

The Mitsubishi Nagasaki Shipyard ruling was a landmark because it provided the Supreme Court's first clear and comprehensive articulation of the LSA working time concept. By adopting the "direction and command" standard as an objective test, the Court significantly clarified that an employer's actual control or constraint over an employee's time and actions is decisive, rather than what might be written in employment agreements or company policies. If an employer requires certain activities, makes them unavoidable for the performance of the main job, or enforces them with disciplinary consequences, the time spent on such activities is likely to be considered working time if it occurs under the employer's purview (e.g., on company premises) and is integral to the work process.

This standard effectively incorporates an element of compulsion or employer-imposed obligation. Academic discussion has explored how this "direction and command theory" relates to other nuanced theories, such as those that explicitly integrate the "work nature" (業務性 - gyōmusei) of an activity or propose a two-factor analysis (employer direction and work content). Some commentators suggest that the Supreme Court's formulation in the Mitsubishi case, by focusing on activities "obligated or effectively compelled" by the employer, substantially incorporates the "work nature" element, thereby aligning in practice with these other influential theories. However, the official case officer commentary (chosakan kaisetsu) on the Mitsubishi ruling suggested that under a stricter "Limited Direction and Command Theory" (which more heavily emphasizes the activity being akin to core work), simply changing clothes might not qualify as working time, indicating that some theoretical distinctions and their practical implications might remain.

Implications for Employers

The Mitsubishi Nagasaki Shipyard case has had lasting implications for how employers in Japan must account for working time:

- Mandated Activities are Key: Any activities that an employer requires, mandates, or makes practically unavoidable for the proper performance of an employee's main duties are likely to be considered working hours, even if they are preparatory (pre-shift) or concluding (post-shift) in nature. This includes tasks like putting on company-mandated uniforms or safety equipment at the workplace, attending compulsory pre-shift meetings, or performing essential clean-up related to the job.

- Work Rules Cannot Override LSA: Simply stating in work rules or employment contracts that certain preparatory or finishing times are not working hours, or are to be performed "off the clock," will be ineffective if the objective "direction and command" test determines that employees are, in fact, under the employer's control and performing necessary, obligated activities during those times.

- Careful Assessment Required: Employers need to meticulously assess all activities that employees are required or practically compelled to perform in relation to their jobs. This includes considering where these activities occur (e.g., on company premises), whether they are essential for the work, and what sanctions (explicit or implicit) exist for non-performance.

- "Socially Necessary" Time: The Court also noted the time must be "socially recognized as necessary." This implies that an unreasonable amount of time spent on such activities, even if mandated, might not be fully counted.

Broader Context and Future Considerations

The Mitsubishi case primarily addressed "non-core activity time" directly associated with the workday. However, the fundamental "direction and command" principle it established is also informative for analyzing other types of potentially disputed time, such as "inactive time" (e.g., on-call waiting periods, standby time), which was more directly addressed in a subsequent Supreme Court case (the Ooboshi Building Management case).

The legal definition of working time continues to face challenges with the evolution of work styles. The rise of remote work, flexible hours, platform-based labor, and the increasing blurriness between work life and personal life may test the traditional understanding of "direction and command," which often involved clear temporal and spatial constraints. The core purposes of LSA working time regulations—protecting worker health and ensuring employees have adequate personal time for family, social, and cultural activities—remain paramount. As work transforms, there is ongoing discussion about whether the emphasis in defining working hours might need to shift further, perhaps incorporating a broader understanding of "work nature" or "job-relatedness" to adequately capture modern employment realities while upholding the LSA's protective goals. Some theories, like the "Complementary Two-Factor Theory" (considering employer direction and work content together), attempt to provide a framework responsive to these changes. However, the concept of "direction and command" is foundational to distinguishing employment contracts from other forms of work, suggesting that its evolution, rather than abandonment, will be key to navigating future labor law challenges.

Conclusion

The Mitsubishi Heavy Industries Nagasaki Shipyard Supreme Court decision was a watershed moment in Japanese labor law. It firmly established the "direction and command" standard as the objective test for determining what constitutes "working hours" under the Labor Standards Act. This ruling has had a significant and lasting impact, particularly by clarifying that preparatory and finishing activities, when mandated or effectively compelled by the employer and performed on its premises as a necessary part of the work process, must be treated and compensated as working time. While new forms of work continue to pose challenges to traditional definitions, the core principle of objective assessment based on employer control remains a critical guidepost for ensuring fair labor practices in Japan.