Beyond the Car Doors: A 2007 Japanese Supreme Court Ruling on Passenger Injury Insurance and Post-Accident Egress

Judgment Date: May 29, 2007

Court: Supreme Court, Third Petty Bench

Case Name: Insurance Claim Case

Case Number: Heisei 18 (Ju) No. 2053 of 2006

Introduction: The Perils Following an Initial Crash

Passenger Injury Insurance (搭乗者傷害保険 - tōjōsha shōgai hoken) is a vital part of many automobile insurance policies in Japan. It is designed to provide compensation if an insured person is injured or killed as a result of an accident. Typically, for coverage to apply, the policy requires that the injury or death must be caused by an "accident arising from the operation" (運行に起因する事故 - unkō ni kiin suru jiko) of the insured vehicle, and often specifies that the insured person must be "riding in" (搭乗中の者 - tōjō-chū no mono) the vehicle at the time.

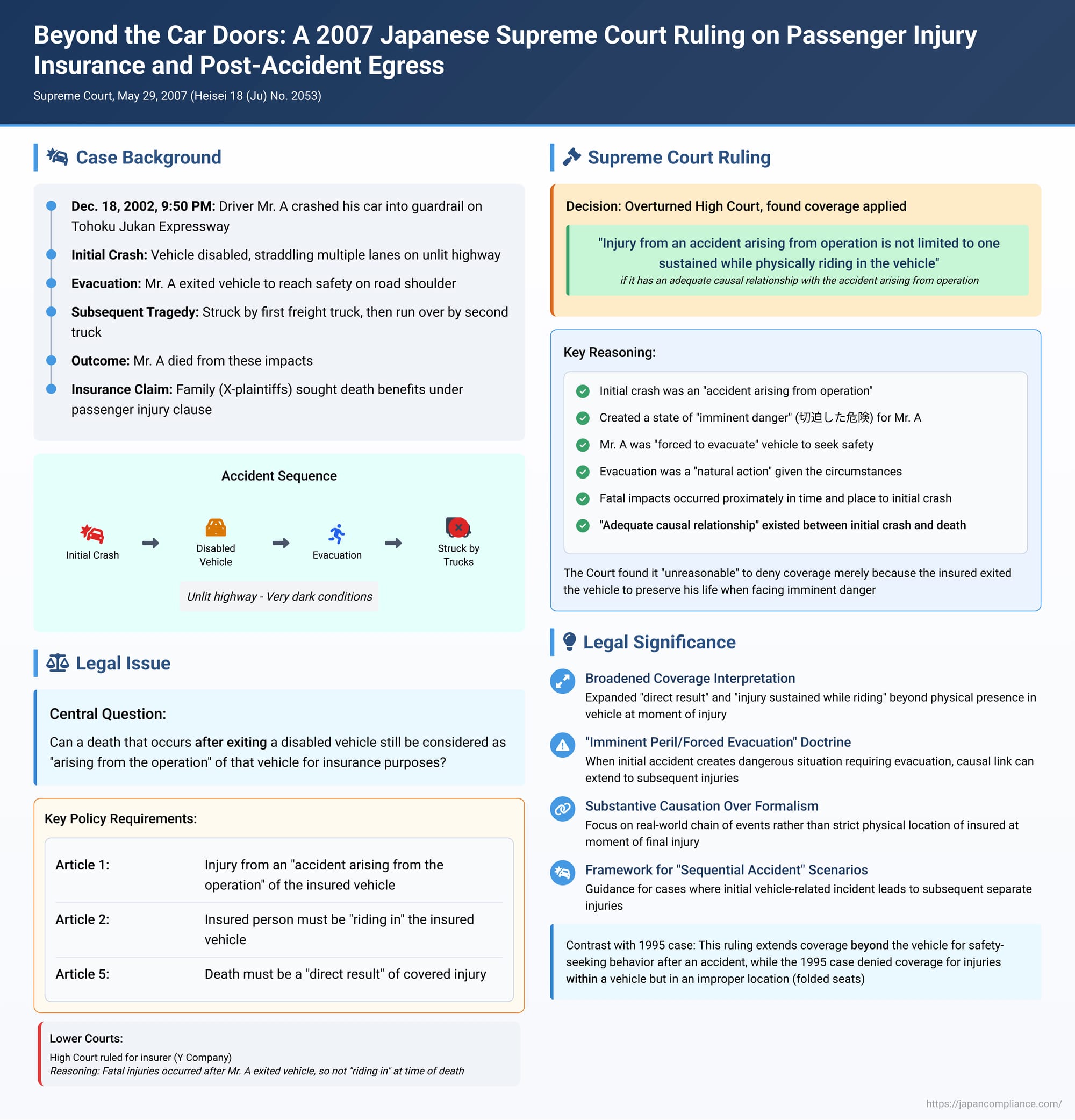

But what happens in a scenario where an initial accident – say, a self-caused crash – disables the insured vehicle on a dangerous, unlit highway? If the driver then exits the vehicle in a desperate attempt to reach safety, only to be tragically struck and killed by subsequent passing traffic, does this death still qualify as a "direct result" of an "accident arising from the operation" of the insured vehicle? Is the critical causal link maintained even though the fatal impact occurred outside the car, after the driver had already alighted? This complex and poignant question, testing the boundaries of causation and the scope of "injury sustained while riding," was addressed by the Supreme Court of Japan in a significant 2007 decision.

The Tragic Sequence of Events on a Dark Highway

The case involved a driver, Mr. A. On the night of December 18, 2002, around 9:50 PM, Mr. A was driving his car (referred to as "the subject vehicle") on the Tohoku Jukan Expressway, a major highway. For reasons that were not definitively established, he lost control of his vehicle and crashed it into a guardrail along the central median. This initial collision (referred to as "the subject self-caused accident") caused significant damage to his car, rendering it disabled and undriveable. The vehicle came to a stop straddling both the driving lane and the passing lane of the expressway. Critically, the accident occurred in a section of the highway that had no streetlights and was, therefore, very dark.

Recognizing the extreme and immediate danger of remaining inside his stationary, disabled vehicle in the middle of an unlit, high-speed expressway at night, Mr. A made a rapid decision. He immediately got out of his car and began to run across the active driving lane, heading towards the relative safety of the road shoulder on the left side.

Just as he reached the vicinity of the shoulder, a large freight truck, attempting to pass between Mr. A's disabled car and the road shoulder, either struck him directly or brushed him with sufficient force to cause him to fall to the ground. Immediately thereafter, a second large freight truck, which had been following the first one, ran over Mr. A. He was killed as a result of these impacts.

Mr. A's family (the X-plaintiffs, comprising his wife and children) subsequently filed a claim for death benefits under the Passenger Injury Clause of the automobile insurance policy that covered Mr. A's car. This policy had been taken out by Mr. A's employer, B Company, with Y Insurance Company (formerly Sompo Japan).

The Policy Wording and the Insurer's Defense

The relevant Passenger Injury Clause in the insurance policy stipulated several conditions for payment:

- Article 1: The insurer (Y Company) would pay insurance benefits if an "insured person" suffered bodily injury (which included gas poisoning) as a result of a "sudden, fortuitous, and external accident" that was, specifically, an "accident arising from the operation" of the insured vehicle.

- Article 2: An "insured person" was defined, for the purposes of this clause, as a person "riding in" the insured vehicle's proper passenger-carrying device or within the passenger compartment where such a device was located (excluding any areas partitioned off and inaccessible from the main passenger area).

- Article 5: The insurer would pay the full death benefit amount (in this case, 10 million yen per person) to the insured person's statutory heirs if the insured person suffered an injury as described in Article 1 and, "as a direct result thereof" (その直接の結果として - sono chokusetsu no kekka toshite), died within 180 days of the date of the accident.

Y Insurance Company denied the family's claim. Its primary argument was that Mr. A's death did not meet these policy conditions. It contended that Mr. A was not significantly injured, if at all, in the initial self-caused accident itself (the collision with the guardrail). His fatal injuries, the insurer argued, were caused by subsequent, separate accidents – namely, being struck and then run over by the two passing trucks. Crucially, these fatal impacts occurred after Mr. A had exited the insured vehicle and was therefore no longer "riding in" it as required by Article 2. Consequently, Y Insurance Company asserted, his death was not a "direct result" of an injury sustained from an "accident arising from the operation" of the insured vehicle while he was an insured passenger in the manner contemplated by the policy.

Lower Courts' Conflicting Rulings

The case saw differing outcomes in the lower courts:

- Court of First Instance (Sendai District Court, Ogawara Branch): This court ruled in favor of Mr. A's family (the X-plaintiffs), finding that the death was covered by the Passenger Injury Clause and ordering Y Insurance Company to pay the benefits.

- Appellate Court (Sendai High Court): On appeal by Y Insurance Company, the High Court reversed the first instance decision and ruled in favor of the insurer, denying the family's claim. The High Court's reasoning was largely aligned with the insurer's arguments. It found that there was no proof Mr. A had suffered any significant injury in the initial self-caused accident while he was inside the vehicle. Even if he had sustained some minor injury then, his subsequent death from being struck and run over by the trucks (after he had, in the High Court's view, voluntarily exited the car) was not a "direct result" of any injury sustained in that initial operating accident.

Mr. A's family then appealed this adverse appellate ruling to the Supreme Court of Japan.

The Supreme Court's Decision (May 29, 2007): Causation Extended Beyond the Confines of the Vehicle

The Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench, overturned the Sendai High Court's decision. It ruled in favor of Mr. A's family, holding that Y Insurance Company was indeed liable to pay the death benefits under the Passenger Injury Clause. The Supreme Court's reasoning focused on a broader, more substantive interpretation of causation and the scope of the policy's coverage in such perilous, sequential accident scenarios:

Focus on the Initial "Accident Arising From Operation"

The Supreme Court began by affirming two preliminary points:

- Mr. A, as the driver of the insured vehicle, clearly qualified as an "insured person" under the terms of the policy.

- The initial "self-caused accident" – Mr. A losing control of his car and crashing it into the guardrail, causing it to become disabled on the highway – unequivocally constituted an "accident arising from the operation" of the insured vehicle, as required by Article 1 of the policy.

The Concept of "Imminent Danger" and "Forced Evacuation"

The crux of the Supreme Court's decision lay in its assessment of the situation created by this initial operating accident:

- The Court emphasized the specific circumstances: Mr. A's car was disabled, straddling two lanes of a high-speed expressway, at night, in an unlit area.

- This situation, the Supreme Court found, placed Mr. A in a state of "imminent danger" (切迫した危険 - seppaku shita kiken). If he had remained inside his disabled and dangerously positioned vehicle, he faced a very high risk of suffering severe bodily harm or death from potential collisions with subsequent, unsuspecting vehicles.

- Consequently, the Court concluded, Mr. A was effectively "forced to evacuate" (車外に避難せざるを得ない状況に置かれた - shagai ni hinan sezaru o enai jōkyō ni okareta) the vehicle in order to seek safety. His act of exiting the car and attempting to reach the road shoulder was not merely a casual or entirely voluntary decision disconnected from the initial accident; rather, it was a necessary and direct response to the perilous and life-threatening situation that the initial operating accident had created.

Establishing an "Adequate Causal Relationship" (相当因果関係 - Sōtō Inga Kankei)

Building on this finding of "forced evacuation" from "imminent danger," the Supreme Court then addressed the causal link between the initial accident and Mr. A's subsequent death:

- The Court determined that Mr. A's actions following the initial crash – exiting the vehicle, running across a lane of traffic towards the shoulder, and then being tragically struck and run over by the passing trucks – were, given the dire circumstances, a "natural action" (極めて自然なもの - kiwamete shizen na mono) for someone facing such imminent danger.

- The fatal impacts occurred proximately in both time and place to the initial self-caused accident that had necessitated his evacuation.

- The Court stated that it was "not expectable that Mr. A could have acted differently" in that life-threatening situation. He was compelled to take the evasive action he did.

- Therefore, the Supreme Court concluded that there was an "adequate causal relationship" between the initial "accident arising from operation" (the self-caused crash that disabled his car in a dangerous position) and Mr. A's eventual death by being struck and run over by the subsequent trucks.

- Based on this strong causal link, the Court found it reasonable to interpret that Mr. A was injured (ultimately fatally) as a result of the initial self-caused operating accident, because that accident set in motion an unbroken and foreseeable chain of events that directly led to his death.

Reinterpreting "Injury Sustained While Riding In" for the Purpose of Coverage

The Supreme Court directly confronted Y Insurance Company's argument that coverage should be denied because Mr. A's fatal injuries were physically sustained outside the vehicle and because he may not have been significantly injured while he was physically inside the car during the initial impact with the guardrail.

- The Court stated that to deny coverage solely on this basis would be to "ignore the adequate causal relationship" that it had found to exist between the initial operating accident and Mr. A's death. Such a denial, the Court held, would "not be appropriate."

- The Supreme Court further bolstered its reasoning by pointing out the inherent "unreasonableness" of a coverage rule that would lead to the following distinction: if a person remains inside a dangerously disabled vehicle in a situation of imminent peril and is then further injured or killed by a subsequent impact (e.g., another car crashing into the disabled one), they would presumably be covered by passenger injury insurance. However, if that same person, facing the exact same imminent danger, makes a reasonable attempt to exit the vehicle to preserve their life and is then injured or killed just outside it as a direct consequence of that perilous situation, they would be denied coverage. The Court found such a distinction to be illogical and unfair.

The New Interpretive Rule Established by the Supreme Court

Based on this comprehensive analysis, the Supreme Court articulated a key interpretive principle for such "sequential accident" scenarios:

"Under the subject Passenger Injury Clause, an injury to an insured person caused by an accident arising from the operation of the insured vehicle is not limited to one sustained by the insured person while [physically] riding in the insured vehicle, as long as it [the injury] has an adequate causal relationship with the accident arising from operation."

Analysis and Key Implications

This 2007 Supreme Court of Japan decision significantly clarified and arguably broadened the interpretation of key phrases like "direct result" and "injury sustained while riding in" as they apply to Passenger Injury Insurance coverage.

1. Broadening the Scope of "Direct Result" and "Injury Sustained While Riding":

The judgment's most profound impact is its establishment that the injury which leads to a covered outcome (such as death or disability) under a Passenger Injury Insurance clause does not strictly have to occur while the insured person is physically inside the insured vehicle at the precise moment that injury is sustained. Coverage can extend to injuries sustained outside the vehicle, provided there is a strong and unbroken chain of causation (an "adequate causal relationship") linking those external injuries back to an initial "accident arising from the operation" of that vehicle.

2. The Significance of the "Imminent Peril" or "Forced Evacuation" Doctrine:

The Supreme Court's emphasis on Mr. A having been placed in a situation of "imminent danger" by the initial operating accident, which in turn "forced him to evacuate" the vehicle, is crucial. This reasoning suggests that the causal link between the initial operating accident and subsequent external injuries can be maintained if the insured's act of leaving the vehicle is not viewed as a purely voluntary, independent, or disconnected act. Instead, if exiting the vehicle is a direct, necessary, and reasonable response to a perilous situation created by that initial operating accident, the chain of causation can remain intact for insurance coverage purposes. This approach bears resemblance to "rescue" or "emergency action" doctrines that are sometimes seen in tort law, where actions taken to avert a greater harm created by an initial wrong are still considered consequences of that initial wrong.

3. Prioritizing Substantive Causation Over Formal Location of Injury:

The Supreme Court, in this decision, clearly prioritized a substantive assessment of the chain of causation over a strictly formalistic interpretation of where the fatal injury physically occurred (i.e., inside versus outside the vehicle). If the sequence of events, including the insured's actions in response to a vehicle-related peril, flows foreseeably and naturally from an initial covered "accident arising from operation," then insurance coverage can follow that chain of events.

4. Consistency with the Protective Aims of Passenger Injury Insurance and Avoidance of Unreasonable Outcomes:

The Court's reasoning, particularly its comment about the unreasonableness of denying coverage to someone who exits a dangerously disabled car in an emergency (while potentially covering someone who remains inside and suffers further harm), reflects a clear concern for achieving sensible and fair outcomes that are aligned with the fundamental protective purpose of passenger injury insurance. It seeks to avoid creating arbitrary distinctions in coverage that do not reflect the realities of dangerous post-accident situations.

5. Providing Important Guidance for "Sequential Accident" Scenarios:

This case offers vital guidance for insurers, policyholders, and legal practitioners when dealing with "sequential accident" scenarios. These are situations where an initial incident directly related to the vehicle's operation leads to a second, distinct incident that ultimately causes or exacerbates the insured's injury or leads to their death. The key determinant for coverage in such cases will be the strength and nature of the causal link ("adequate causal relationship") between the first (covered operating) event and the ultimate injury or death.

6. Impact on Insurers' Assessment of Complex Claims:

Following this ruling, insurers, when faced with claims where the final injury or death occurs outside the insured vehicle after an initial operating accident, must now carefully consider the specific circumstances that led the insured to exit the vehicle. They need to assess whether that act of exiting was a compelled and reasonable response to a significant danger created by the initial accident itself.

7. Distinguishing from Cases Involving Improper Location Within the Vehicle:

As legal commentary points out, it is useful to contrast this 2007 Supreme Court decision with an earlier one from 1995 (discussed in the user's previous file, h38.pdf). In that 1995 case, passenger injury coverage was denied because the passenger, at the time of the accident, was found to be riding in a part of the vehicle (a folded-down rear seat area being used for cargo) that was not deemed to be a "proper passenger-carrying place" as required by the policy. That earlier case turned on the initial location within the vehicle being improper for passenger carriage from the outset. The 2007 case, however, deals with a situation where the insured driver (Mr. A) was properly "riding in" and operating the vehicle when the initial "accident arising from operation" occurred. The subsequent fatal injury, though sustained outside the vehicle, was linked back by the Supreme Court to that initial covered event through the chain of compelled evacuation from imminent peril.

Conclusion

The May 29, 2007, Supreme Court of Japan decision significantly clarified and expanded the understanding of coverage under Passenger Injury Insurance clauses for injuries or deaths that occur in a sequence of events initiated by an "accident arising from the operation" of the insured vehicle.

It established the important principle that such coverage is not strictly limited to injuries that are physically sustained while the insured person is inside the vehicle at the exact moment of that injury. If an initial "accident arising from operation" places an insured person in a situation of imminent peril, thereby compelling them to evacuate the vehicle as a reasonable measure to ensure their safety, and they are subsequently injured or killed as a direct and foreseeable consequence of that perilous situation and their reasonable attempts to escape it, such injuries or death can be deemed to be "a direct result" of the initial operating accident and thus fall within the scope of coverage. This is provided that an "adequate causal relationship" can be established between the initial operating accident and the ultimate harm.

This ruling emphasizes a substantive and purposive approach to the interpretation of insurance policy language. It encourages a focus on the real-world chain of events set in motion by a covered risk, rather than on overly formalistic limitations based on the precise physical location of the insured at the moment of final injury. The decision ensures that insurance coverage can respond reasonably and fairly to the realities of dangerous post-accident environments, particularly when an insured individual is forced to take action to preserve their own safety in the face of a hazard created by the operation of their vehicle.