Beyond the Call of Duty: The State's Obligation to Protect Its Servants – A 1975 Japanese Supreme Court Landmark

Date of Judgment: February 25, 1975

Case: Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench, Case No. 383 (o) of 1973 (Damages Claim Case)

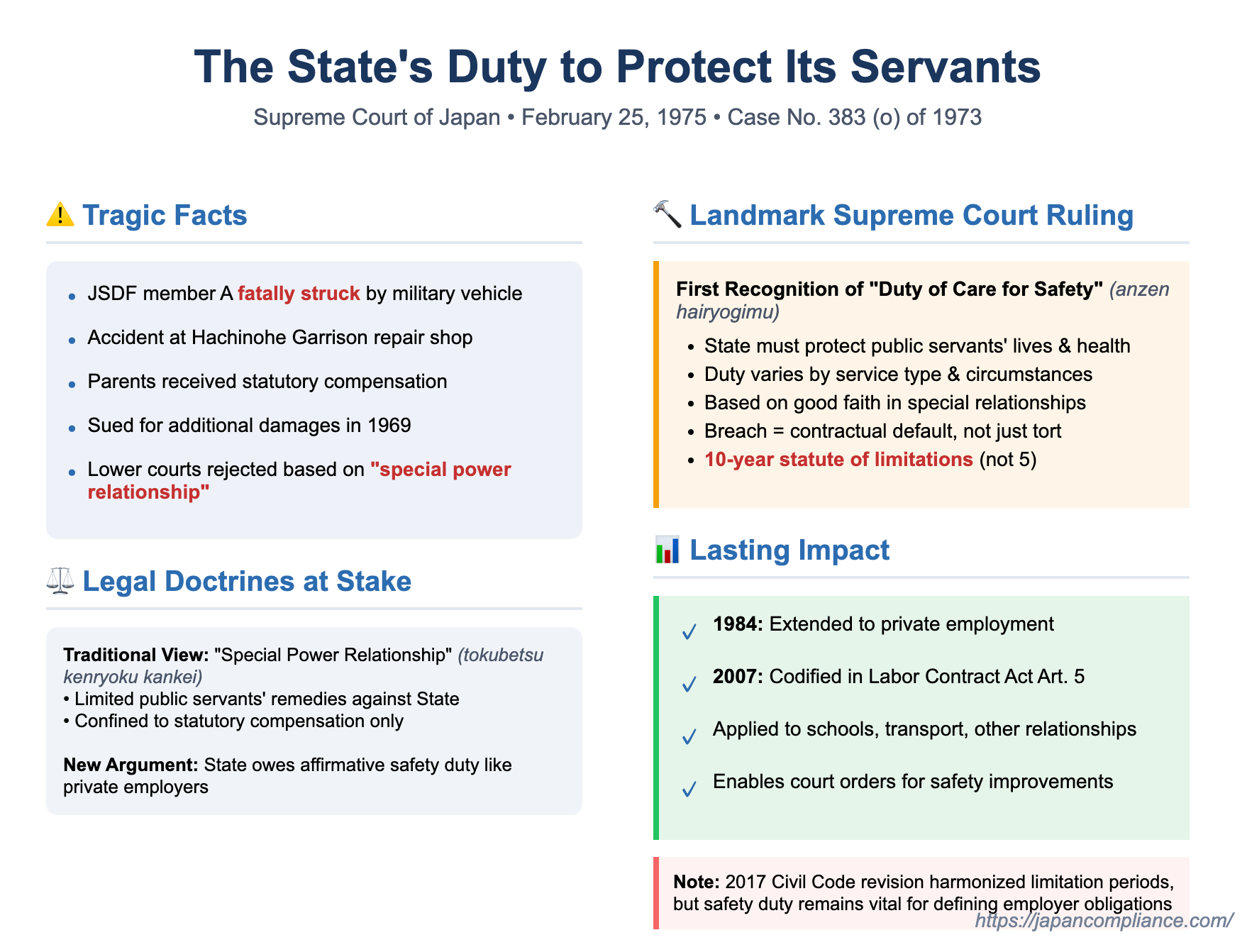

The relationship between a state and its public servants has often been viewed through a unique legal lens. In Japan, traditionally, the concept of a "special power relationship" (tokubetsu kenryoku kankei) implied a degree of heightened state authority and, at times, limited recourse for public servants harmed in the line of duty beyond statutory compensation schemes. However, a groundbreaking 1975 decision by the Supreme Court of Japan marked a significant shift, establishing that the State owes its employees a positive "duty of care for safety" (anzen hairyogimu), a concept that has since profoundly influenced Japanese employment and contract law.

A Tragic Accident in the Line of Duty: Facts of the Case

The case arose from the death of A, a member of the Japan Self-Defense Forces (JSDF). On July 13, 1965, while engaged in vehicle maintenance tasks at the JSDF Hachinohe Garrison's 9th Ordnance Unit vehicle repair shop, A was fatally struck in the head by the rear wheel of a large military vehicle being operated by another JSDF member, B. A died instantly.

A's parents, X1 and X2 (the plaintiffs and appellants), were informed of their son's death the following day and subsequently received statutory workers' compensation benefits (specifically, National Public Servant Disaster Compensation) around July 17, 1965. Some time later, X1 and X2 became aware that they might have grounds to seek further damages from the State (Y, the defendant and respondent). On October 6, 1969, they filed a lawsuit against the State, initially basing their claim on Article 3 of the Automobile Liability Security Act (自賠法 - jibaishōhō), seeking compensation for A's lost future earnings and solatium for their suffering.

The first instance court dismissed X1 and X2's claim. It found that their damages claim under the Automobile Liability Security Act was barred by the statute of limitations, as too much time had passed since the accident.

In their appeal to the High Court, X1 and X2 introduced an additional, crucial legal argument. They contended that the State, as A's employer, bore a fundamental duty to ensure that A's life was not exposed to undue danger during his service. This duty, they argued, included maintaining a safe working environment in terms of both physical conditions (material environment) and personnel deployment (human environment). They asserted that the State had negligently breached this duty, and as a result, was liable for damages based on contractual default. However, the High Court also dismissed their appeal. It reasoned that because A was serving the State under the framework of a "special power relationship," the State did not bear liability for damages based on a breach of such a safety duty (i.e., a contractual default theory). X1 and X2 then appealed this decision to the Supreme Court.

The Legal Landscape: "Special Power Relationship" vs. Emerging Safety Duties

The High Court's reliance on the "special power relationship" (tokubetsu kenryoku kankei) doctrine reflected a traditional view in Japanese administrative law. This doctrine historically posited that public servants were in a relationship of heightened submission to state authority, which could limit their rights and remedies against the State, particularly for work-related injuries, often confining them to statutory compensation schemes rather than general civil damages. The appellants' argument, however, pushed for a recognition of a positive, affirmative duty on the part of the State, akin to that owed by a private employer, to ensure the safety of its personnel, the breach of which would give rise to a claim separate from tort liability.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Recognition of the "Duty of Care for Safety"

The Supreme Court, in its judgment of February 25, 1975, reversed the High Court's decision and remanded the case for further proceedings. This judgment was a watershed moment, as it was the first time Japan's highest court explicitly recognized that the State owes a "duty of care for safety" (anzen hairyogimu) to its public servants.

The Court's key pronouncements were:

- The State's Broader Obligations: The Supreme Court declared that the State's obligations towards its public servants are not confined merely to the payment of salaries. It held that "the State, in the installation and management of places, facilities, or equipment that it should establish for the performance of public duties, or in the management of public duties performed by public servants under the direction of the State or their superiors, bears a duty to take care to protect the lives and health of public servants from danger (hereinafter referred to as 'duty of care for safety')."

- Content and Context of the Duty: The Court acknowledged that the specific content of this safety duty would naturally vary depending on several factors, including the type of public service, the official's rank and position, and the concrete circumstances in which the duty is called into question. In the case of JSDF members, for instance, the nature of the duty could differ significantly depending on whether the service was being performed during routine work, training exercises, defense operations, public security operations, or disaster relief deployments. However, the Court firmly rejected the notion that the State owes no such duty to public servants in any circumstance, apart from its general duties under tort law to protect the lives and health of private citizens.

- Rationale for Recognizing the Duty: The Supreme Court provided a compelling rationale for this duty:

- Good Faith in Special Social Relationships: Such a duty of care for safety should be generally recognized as an ancillary obligation arising from the principle of good faith and trust between parties who have entered into a special social contact based on a legal relationship. There is no logical basis to treat the relationship between the State and its public servants differently in this regard.

- Enabling Faithful Service: For public servants to perform their duties diligently, faithfully, and with peace of mind, it is essential that the State acknowledges and fulfills this duty of care for their safety.

- Presupposition of Statutory Compensation Systems: The existing statutory disaster compensation systems for public servants (such as the National Public Servant Disaster Compensation Act and provisions in the Defense Agency Personnel Remuneration Act) are themselves understood to operate on the premise that the State already bears such a duty of care for safety. These compensation schemes are designed to address public service-related injuries and deaths that may occur even if the State has fulfilled its safety duties.

- Nature of the Claim for Breach: By establishing this duty, a breach by the State could give rise to a claim for damages based on contractual default (債務不履行 - saimu furikō), distinct from a claim in tort.

- Statute of Limitations for Breach of Safety Duty: This was a crucial aspect of the ruling. The Supreme Court held that the statute of limitations for a damages claim against the State arising from a breach of this duty of care for safety is 10 years, pursuant to Article 167, paragraph 1, of the old Civil Code (the general prescription period for contractual claims). It explicitly rejected the application of the shorter 5-year period stipulated in Article 30 of the Public Accounts Act (会計法 - kaikeihō) for general monetary claims by or against the State. The Court reasoned that the 5-year period under the Public Accounts Act was primarily for administrative convenience in settling routine financial matters and did not apply to damages claims for personal injury or death resulting from a breach of the safety duty. Such claims, aimed at fair compensation for harm, are analogous in purpose and nature to private law damages claims and should not be subjected to a shorter administrative limitation period.

- Error of the High Court: The Supreme Court concluded that the High Court had erred in law by dismissing the plaintiffs' claim based solely on the "special power relationship" doctrine, without properly considering the State's duty of care for safety and the potential breach thereof.

Unpacking the "Duty of Care for Safety"

The anzen hairyogimu doctrine, as established by this 1975 judgment, has several key characteristics:

- A Contractual or Relational Obligation: It arises as an ancillary or implied duty from the underlying legal relationship between the State (or employer) and the public servant (or employee). Its breach gives rise to liability based on contractual default principles.

- Content Determined Case-by-Case: The specific actions required to fulfill this duty are not fixed but depend heavily on the context. For example, in an employment setting, this might include duties to maintain a safe physical work environment, ensure proper training and supervision, implement appropriate safety protocols, and comply with relevant health and safety legislation. In cases of occupational diseases or overwork leading to illness or death, the duty encompasses taking measures to prevent such harm and to avoid its aggravation.

- Distinction from Tort Liability (Historically Crucial for Limitations): One of the most significant practical consequences of recognizing this duty as contractual was, historically, the applicable statute of limitations. Tort claims in Japan (under Article 724 of the old Civil Code) were subject to a relatively short 3-year limitation period from the time the victim (or their heirs) became aware of the damage and the identity of the person liable. In contrast, claims based on contractual default, including breach of the safety duty, benefited from the general 10-year limitation period under Article 167, paragraph 1, of the old Civil Code. This often made the safety duty claim a more viable option for victims, especially when awareness of the legal basis for a claim was delayed.

It is important to note, however, that the 2017 revisions to the Japanese Civil Code (effective 2020) have significantly harmonized the statute of limitations for damages claims involving loss of life or bodily injury. Both contractual and tort claims in such cases are now subject to longer and more aligned limitation periods (see current Civil Code Articles 167 and 724-2). This has somewhat diminished the strategic importance of the safety duty claim solely for the purpose of accessing a longer limitation period.

Development and Expansion of the Doctrine

The principle of anzen hairyogimu articulated in the 1975 JSDF case was not confined to the relationship between the State and public servants.

- Private Employment: The Supreme Court explicitly extended this duty to private employment contracts in a landmark decision on April 10, 1984 (Minshu Vol. 38, No. 6, p. 557).

- Other Relationships: Lower courts have subsequently recognized similar duties of care in various other relational contexts, such as between educational institutions and students, and between transport operators and passengers.

- Codification: The concept received statutory recognition with the enactment of the Labor Contract Act in 2007, Article 5 of which explicitly states: "An employer shall, in an employment contract, pay necessary consideration for the worker to be able to work safely by ensuring the safety of his/her life, body, etc.".

Current Relevance and Interaction with Tort Law

Even with the harmonization of limitation periods for personal injury and death claims, the concept of a contract-based duty of care for safety remains relevant in Japanese law.

- Defining Contractual Obligations: It continues to inform the scope of obligations implicitly arising from specific relationships, particularly employment.

- Potential for Specific Performance: One area where the contractual nature of the safety duty might still offer distinct advantages over a pure tort claim is the possibility of seeking specific performance—that is, a court order compelling an employer or the State to take specific measures to improve safety or rectify dangerous conditions. While tort law primarily provides for damages, and injunctive relief in tort can be complex, a contractual duty might offer a more direct basis for demanding proactive safety measures. However, this area is also subject to ongoing legal debate regarding the interplay with tort-based injunctions.

- Theoretical Debates: There is ongoing scholarly discussion about whether the duties imposed under the anzen hairyogimu doctrine are truly distinct from the duties of care that would be imposed by general tort law in similar relational contexts (e.g., through the concepts of foreseeable harm or duties arising from a relationship of control or dependence). Some argue that tort law, properly applied, could achieve similar protective outcomes, while others maintain that contractual duties can sometimes be more specific or extensive.

A 1983 Supreme Court decision (Minshu Vol. 37, No. 4, p. 477) somewhat limited the scope of the State's safety duty in a case where a JSDF member was injured due to the negligence of a fellow JSDF member driving a vehicle. The Court held that the State's duty was primarily to ensure a safe material and human environment and did not extend to guaranteeing that every individual performing duties (like driving) would perfectly adhere to all general duties of care (such as traffic laws), which has drawn criticism for potentially narrowing the State's responsibility for the actions of its employees acting as "performance assistants".

Concluding Thoughts

The 1975 Supreme Court decision recognizing the State's "duty of care for safety" towards its public servants was a seminal development in Japanese jurisprudence. It marked a significant departure from older, more restrictive doctrines that limited the State's liability for harm suffered by its personnel in the line of duty. By establishing this duty as a positive obligation rooted in good faith and inherent in the employment-like relationship, the Court opened a crucial avenue for redress based on contractual principles, most notably offering a more favorable statute of limitations at the time. While subsequent legal reforms have harmonized limitation periods for personal injury and death claims, the anzen hairyogimu doctrine remains a vital concept, underpinning employer responsibilities for workplace safety in both public and private sectors, and continuing to shape discussions about the scope of duties owed in various relational contracts. It stands as a testament to the law's capacity to evolve in recognizing and enforcing fundamental protections for individuals even within traditionally hierarchical relationships.