Beyond the Breaking Point: Japan's Supreme Court on Chronic Overwork and Work-Related Illness (July 17, 2000)

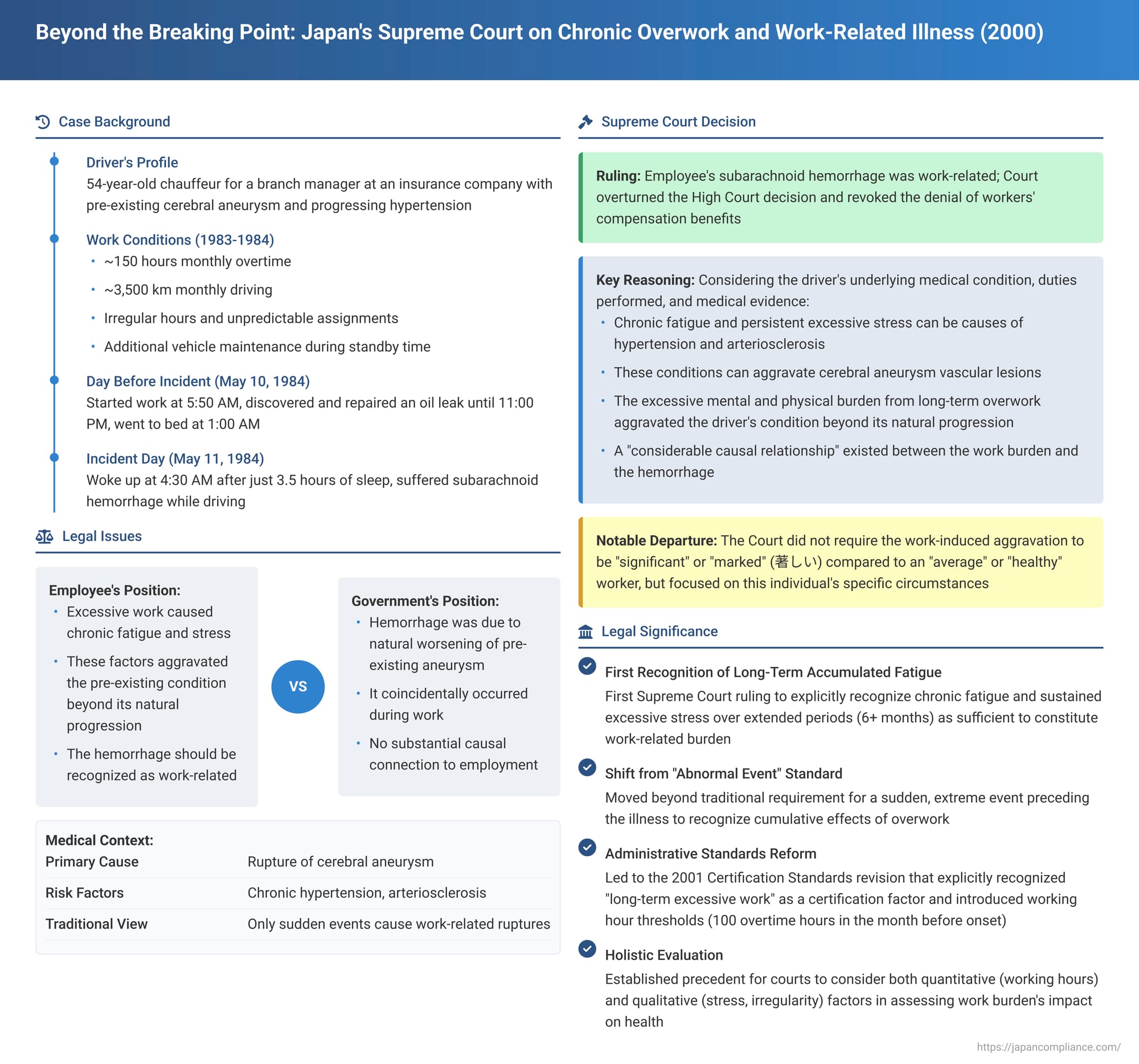

On July 17, 2000, the First Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan delivered a landmark judgment in a workers' compensation case involving a company driver who suffered a subarachnoid hemorrhage. This case, often referred to by commentators as the "Tokio Marine Yokohama Branch Driver Case" (though anonymized here), is pivotal for its recognition of long-term accumulated fatigue and sustained excessive stress as crucial factors in determining whether a serious cerebrovascular event can be classified as a "work-related illness" (業務上の疾病 - gyōmujō no shippei) under Japan's Labor Standards Act (LSA) and workers' compensation laws.

A Driver's Grueling Schedule: The Path to Collapse

The plaintiff, X, was employed as a dedicated driver for the branch manager of the Yokohama branch of Insurance Company I. X's responsibilities were extensive and demanding:

- Core Duties: X's primary role involved chauffeuring the branch manager for commutes, visits to other branch offices, client calls, and attendance at business-related entertainment functions at restaurants and golf courses. X also frequently drove other senior staff members and clients of the branch.

- Additional Tasks: Beyond driving, X was responsible for the upkeep of the vehicle, which included cleaning, washing, waxing, and performing minor repairs. These tasks were often carried out during standby periods or after returning the car to the garage.

- Irregular and Unpredictable Hours: X's daily driving schedule was frequently assigned at very short notice, requiring constant alertness and readiness even during standby times.

- Escalating Workload: Following the appointment of a new branch manager in July 1981, X's driving distances significantly increased, and work hours routinely stretched from early morning until late at night.

- Statistical Overview (January 1983 – May 11, 1984): During this period, X's average monthly overtime was approximately 150 hours, and the average monthly driving distance was around 3,500 kilometers.

- Intensification (December 1983 onwards): From December 1983, X's average daily overtime, which included night work, exceeded seven hours, and monthly driving distances remained exceptionally high.

- Events Preceding the Illness (April-May 1984):

- In April 1984, X's average daily overtime continued to be over seven hours, and the average daily driving distance (around 192 km) was the highest it had been since December 1983. During this month, X experienced periods of ill health due to assignments involving long-distance, long-hour driving with overnight stays. One particularly strenuous trip from April 13-14 involved driving 248 km on the first day and 347 km on the second, with an overnight stay where X reportedly got no sleep due to a roommate's snoring, leading to a decline in X's physical condition.

- Between May 1 and May 10, 1984, despite having six intermittent holidays in late April and early May, X had two days where work ended after midnight and two days where driving exceeded 260 kilometers.

- On May 10, 1984 (the day before the incident), X started work at 5:50 AM. Although the driving distance for the day was relatively short at 76 km, X spent standby time washing and waxing the car. After returning to the garage around 7:30 PM, X discovered an engine oil leak while cleaning the vehicle around 7:50 PM and worked on repairing it until approximately 11:00 PM. X finally went to bed around 1:00 AM on May 11.

- The Day of Collapse (May 11, 1984): After only about three and a half hours of sleep, X woke up around 4:30 AM, went to the garage shortly before 5:00 AM, and completed pre-run vehicle checks. Soon after leaving the garage to pick up the branch manager, X felt unwell while driving and suffered a subarachnoid hemorrhage.

Plaintiff X's Health Profile

- X (54 years old at the time of the incident) was considered highly likely to have had a pre-existing condition that could lead to a subarachnoid hemorrhage, specifically a cerebral aneurysm (脳動脈りゅう - nō dōmyaku ryū).

- X also had progressing hypertension (high blood pressure), which is a known risk factor for subarachnoid hemorrhage. However, health check-ups in October 1981 and October 1982 indicated that X's blood pressure was in the borderline normal/high range and not considered severe enough to necessitate medical treatment at that time.

- X had no personal habits (such as drinking or smoking) recognized as detrimental to health.

- From around 1983, X's physical appearance had reportedly deteriorated; X often looked pale, had bloodshot eyes, appeared irritable, and frequently complained of insufficient sleep, despite having a naturally stoic personality.

Medical Context of Subarachnoid Hemorrhage

The judgment and commentary provide some medical background:

- Subarachnoid hemorrhage is often caused by the rupture of a cerebral aneurysm. While traditionally thought to be congenital, some views suggest aneurysms can also develop later in life; the origin of X's potential aneurysm was unknown.

- The direct causal link between the development of cerebral aneurysms and hypertension is not fully established.

- However, vascular lesions associated with cerebral aneurysms are believed to be aggravated by chronic hypertension and arteriosclerosis (hardening of the arteries). Chronic hypertension is generally cited as a risk factor for subarachnoid hemorrhage.

- Aneurysms typically rupture when their walls, thinned and enlarged by sustained chronic high blood pressure, reach a critical point and are subjected to a transient surge in blood pressure. Such surges are often linked to everyday physical activities like defecation or bending forward, rather than solely to generally high blood pressure or mental stress.

- While chronic fatigue and prolonged excessive stress are not considered direct causes of subarachnoid hemorrhage itself, they can be one of the causes of chronic hypertension and arteriosclerosis, which in turn aggravate aneurysms.

The Legal Battle for Compensation

Following the subarachnoid hemorrhage, X applied for work absence compensation benefits under Japan's Workers' Accident Compensation Insurance Act. Defendant Y, the Director of the Yokohama South Labor Standards Inspection Office, denied the application, concluding that the illness was not work-related. X then sued to have this non-payment decision revoked.

- First Instance (Yokohama District Court): The District Court ruled in favor of Plaintiff X. It acknowledged the likely presence of a pre-existing cerebral aneurysm as a contributing factor but found that X's excessively demanding work had imposed a significant physical and mental burden. This burden, the court concluded, had aggravated X's underlying condition beyond its natural course of progression, ultimately leading to the hemorrhage. Thus, the illness was deemed work-related.

- Appeal (Tokyo High Court): The High Court overturned the District Court's decision, ruling in favor of Defendant Y. It determined that the subarachnoid hemorrhage was primarily due to a cerebral aneurysm that had worsened naturally with age and coincidentally ruptured while X happened to be engaged in driving duties. Therefore, it was not considered a work-related illness.

Plaintiff X appealed this adverse ruling to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Decisive Intervention: Recognizing the Impact of Chronic Overwork

The Supreme Court overturned the High Court's judgment and effectively reinstated the first instance court's decision, thereby recognizing X's subarachnoid hemorrhage as a work-related illness.

The Court's reasoning was as follows:

"Considering X's above-described underlying medical condition and its extent, the content, manner, and circumstances of the duties X was engaged in before the onset of this subarachnoid hemorrhage, and additionally, that cerebral aneurysm vascular lesions are considered to be aggravated by chronic hypertension and arteriosclerosis, and that chronic fatigue and the persistence of excessive stress can be one of the causes of chronic hypertension and arteriosclerosis, it is difficult to view X's said underlying condition as having worsened through its natural course by the time of onset to such an extent that any transient rise in blood pressure would immediately cause a rupture".

"In this case, where no other definite aggravating factors can be found, it is reasonable to conclude that the excessive mental and physical burden from the duties X performed before the onset aggravated X's said underlying condition beyond its natural progression, leading to the said onset, and a considerable causal relationship can be affirmed between them".

"Therefore, the subarachnoid hemorrhage that X developed" qualifies as a work-related illness under the LSA Enforcement Regulations, Annexed Table 1-2, then Item 9 (now Item 11), as an "other disease clearly resulting from employment".

Unpacking "Work-Related Illness": The Evolution of Standards

This Supreme Court decision is particularly significant for its approach to determining "work causation" (業務起因性 - gyōmu kigen-sei) in cases of cerebrovascular and cardiovascular diseases, which often involve pre-existing conditions.

- The Challenge of Causation: Such diseases are typically multifactorial, influenced by underlying health issues, aging, lifestyle, and work. Establishing a clear link to employment can be complex.

- Evolving Administrative Certification Standards (通達 - tsūtatsu): The criteria used by Labor Standards Inspection Offices to certify such illnesses as work-related have evolved over time:

- An early standard (Showa 36, 1961) primarily recognized work causation if an "abnormal event" (e.g., a sudden, extreme shock or exertion at work) immediately preceded the illness. Simple accumulated fatigue was generally not considered a sufficient work-related burden under this standard.

- Influenced by court decisions that began to recognize chronic overwork as a significant factor (e.g., the 1970 Kokuritsu Kyoto Hospital Case), administrative standards were gradually relaxed. A Showa 62 (1987) circular started to allow for the consideration of short-term (within one week prior to onset) work burdens even without a single "abnormal event".

- By the time of this Supreme Court judgment, further revisions (Heisei 7, 1995, and Heisei 8, 1996) had broadened the criteria to include not only "abnormal events" but also situations where work was "particularly heavy compared to daily duties." This involved evaluating work immediately before onset or within the preceding week, and if work in the last week was significantly heavier, earlier periods could also be considered. However, the commentary notes that the specific role of long-term accumulated fatigue was still not explicitly and clearly defined in these standards.

- Significance of the Supreme Court's Judgment:

- While this judgment was a case-specific ruling rather than one laying down a new general legal framework, its impact was substantial.

- Crucially, it was the first Supreme Court decision to explicitly recognize that chronic fatigue and the sustained presence of excessive stress over an extended period (in this case, at least six months of heavy workload were considered) could constitute a sufficient work-related burden to aggravate a pre-existing condition beyond its natural progression and cause a serious illness like a subarachnoid hemorrhage.

- Notably, the Court did not require the work-induced aggravation to be "significant" or "marked" (著しい - ichijirushii), a term sometimes used in such contexts, nor did it explicitly compare X's workload to that of a hypothetical "average" or "healthy" worker. It focused on X's individual circumstances and the impact of the prolonged, heavy duties on X's specific underlying health conditions.

Post-Judgment Developments: Refining the Standards

This Supreme Court ruling played a key role in prompting further revisions to the official administrative guidelines for certifying cerebrovascular and cardiovascular diseases as work-related.

- The Heisei 13 (2001) Certification Standards, issued following this judgment, explicitly incorporated "long-term excessive work" as a key factor. These standards now recognize that an illness can be work-related if caused by:

- An abnormal event.

- Short-term excessive work (close to the onset).

- Long-term excessive work (typically evaluating the six months prior to onset) leading to significant accumulated fatigue.

- The 2001 standards also detailed factors for assessing the intensity of long-term work, including not just working hours but also irregularity of勤務 (work schedule/shifts), length of time an employee is bound to the workplace (拘束時間 - kōsoku jikan), frequency of business trips, shift work/night work, adverse working environments (temperature, noise, time zone changes), and duties involving constant mental tension.

- Specific working hour thresholds were introduced as guidelines: e.g., overtime of approximately 100 hours in the month before onset, or an average of approximately 80 hours of overtime per month for the two to six months preceding onset, would be considered strong indicators of a link between work and the illness. The "reference worker" for comparison was defined as a healthy person of similar age and experience, or even someone with a pre-existing condition who could nonetheless perform daily duties without hindrance.

- Recent Trends and Further Revisions (Reiwa 3, 2021): Court cases reviewing non-payment decisions since the 2001 standards have often cited these standards but have also shown flexibility, sometimes finding work causation even when strict overtime hour thresholds were not met, by giving weight to qualitative burdens like stress or irregular work. Conversely, some cases denied claims despite long hours if other factors were not compelling. Recognizing these trends and aiming for more appropriate certifications, the standards were revised again in 2021. The new standards maintain the 2001 framework but further clarify the need for a comprehensive evaluation of both working hours and other workload factors when assessing long-term excessive work.

Conclusion: Acknowledging the Toll of Sustained Overwork

The Supreme Court's 2000 judgment in the Insurance Company I Yokohama Branch Driver Case marked a critical step forward in the legal recognition of the health impacts of chronic overwork in Japan. By affirming that prolonged, excessive mental and physical job demands can aggravate pre-existing vulnerabilities beyond their natural course to cause life-threatening conditions, the Court underscored that "work-related illness" encompasses not only acute incidents but also the cumulative toll of sustained occupational stress and fatigue. This decision has significantly influenced administrative standards and judicial practice, fostering a more comprehensive understanding of how modern working conditions can contribute to serious health problems, and reinforcing the employer's responsibility to manage workloads to protect employee health.