Beyond the Boardroom: Directors' Duty to Supervise and Liability to Third Parties in Japan

Case: Action for Damages

Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench, Judgment of May 22, 1973

Case Number: (O) No. 673 of 1971

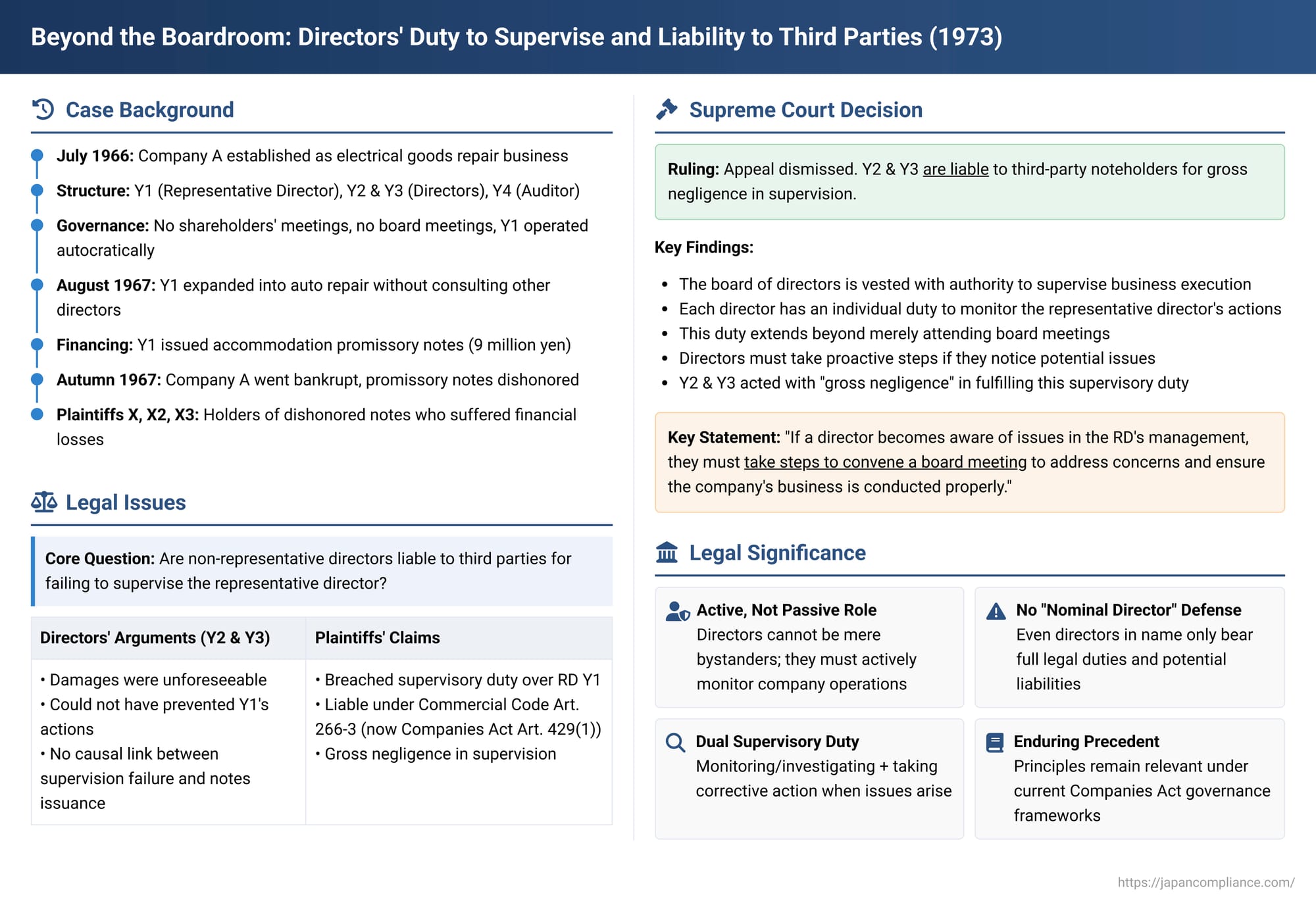

In the corporate structure, while the representative director (RD) is typically the face and primary actor of the company, the board of directors as a whole holds the ultimate responsibility for overseeing the company's business. This oversight function is not merely a passive formality; it entails an active duty for each director to monitor the company's operations and the conduct of its executives. A significant Supreme Court decision on May 22, 1973, underscored the depth of this supervisory duty, particularly for non-representative directors, and affirmed their potential personal liability to third parties if a grossly negligent failure in this duty leads to financial harm.

A Company's Collapse and Dishonored Notes: Facts of the Case

The case involved Company A, an electrical goods repair business established in July 1966. Its governance structure and operational realities were, however, far from conventional:

- Y1 served as the Representative Director.

- Y2 and Y3 (the appellants in this Supreme Court case) were also directors.

- Y4 held the position of statutory auditor.

Despite this formal structure, Company A's corporate governance was profoundly dysfunctional:

- It had never held an inaugural general shareholders' meeting, nor any subsequent shareholders' meetings.

- No formal board of directors' meetings had ever been convened.

- The company's business was effectively run by RD Y1 in an autocratic manner. Y1 was also the controlling shareholder.

- Proper accounting books were largely non-existent, and the statutory auditor, Y4, had not conducted any audits of the company's affairs.

Around August 1967, RD Y1, without consulting his fellow directors (Y2 and Y3), decided to expand Company A's business operations into the automobile repair sector. To raise funds for this new venture, Y1 caused Company A to issue a series of accommodation promissory notes (notes issued to lend the company's credit to another party, rather than for a direct underlying commercial transaction of the company) totaling 9 million yen, payable to an individual named B. However, Y1 was reportedly deceived by B and failed to secure the intended financing. Company A was thus saddled with the liability for these promissory notes without receiving any corresponding benefit. This ill-fated venture quickly led to Company A's collapse; it went bankrupt in the autumn of 1967.

The plaintiffs, X, X2, and X3, were holders of some of these dishonored promissory notes. Due to Company A's bankruptcy, they were unable to obtain payment on the notes and consequently suffered financial losses equivalent to the face value of the notes they held.

Seeking recourse, the plaintiffs filed a lawsuit against the individuals involved in Company A's management: RD Y1, directors Y2 and Y3, and auditor Y4. Their claim was based on the provisions of the then-Commercial Code Article 266-3 (the predecessor to Article 429, Paragraph 1 of the current Companies Act), which deals with the liability of directors (and other officers) to third parties.

- Against RD Y1, the claim was for breach of his duties as representative director.

- Against directors Y2 and Y3, the claim was specifically for breaching their supervisory duty over RD Y1's business execution.

- Against auditor Y4, the claim was for neglecting his audit duties.

The Lower Courts: Finding Directors Y2 & Y3 Negligent in Supervision

The court of first instance (Niigata District Court, Nagaoka Branch) found all four defendants – RD Y1, directors Y2 and Y3, and auditor Y4 – liable to the plaintiffs.

On appeal, the Tokyo High Court affirmed the liability of RD Y1 and directors Y2 and Y3. However, it overturned the decision regarding auditor Y4, dismissing the claim against him. Directors Y2 and Y3, dissatisfied with the High Court's finding of their liability, appealed to the Supreme Court. Their main argument was that the damages suffered by the plaintiffs were unforeseeable by them and that they could not have prevented RD Y1's actions. They also contended that there was no sufficient causal link between their alleged failure in supervision and the specific issuance of the bad promissory notes by Y1 that led to the plaintiffs' losses.

The Supreme Court's Affirmation: Supervisory Duty is Broad and Proactive

The Supreme Court dismissed the appeal of directors Y2 and Y3, thereby upholding their liability to the third-party noteholders.

Reasoning of the Apex Court: Directors Cannot Be Passive Bystanders

The Supreme Court's reasoning focused on the nature and scope of the supervisory duty owed by all directors, including those not serving as representative directors:

- The Board's Fundamental Supervisory Role: The Court began by affirming that the board of directors in a stock company is vested with the authority and responsibility to supervise the execution of the company's business. This is a core tenet of corporate governance.

- Individual Director's Supervisory Duty to the Company: Flowing from the board's collective responsibility, each individual director, as a member of that board, owes a duty to the company. This duty is not limited to merely monitoring and deliberating upon matters that are formally presented to the board at its meetings. Instead, directors have a broader obligation to generally monitor the business execution conducted by the representative director.

- A Proactive Duty to Intervene: This supervisory duty is not passive. If a director becomes aware of issues or potential misconduct in the RD's management of the company, they have a responsibility to take action. This includes, if necessary, taking steps to convene a board meeting themselves, or formally requesting that a board meeting be convened, to address the concerns and ensure, through the collective action of the board, that the company's business is conducted properly and lawfully.

- Gross Negligence of Directors Y2 and Y3: The Supreme Court then stated that, based on the facts as lawfully established by the High Court, the finding that directors Y2 and Y3 had acted with "gross negligence" (重大な過失 - jūdai na kashitsu) in the performance of this supervisory duty, and that this gross negligence caused the plaintiffs to suffer the damages claimed, was justifiable and could be affirmed.

In essence, the Supreme Court found that Y2 and Y3 could not absolve themselves of responsibility by claiming ignorance or powerlessness in the face of RD Y1's autocratic management, especially given the complete absence of normal corporate governance procedures like board meetings. Their failure to insist on proper governance or to monitor Y1's actions constituted a serious lapse in their duties.

Analysis and Implications: Defining Directors' Oversight Responsibilities

This 1973 Supreme Court judgment is a crucial authority in Japanese corporate law, particularly for its articulation of the supervisory duty of non-representative directors and their potential liability to third parties under what is now Article 429, Paragraph 1 of the Companies Act.

- The Director's Supervisory Duty (監視義務 - kanshi gimu):

This case firmly establishes that being a director is not a passive role. Even directors who are not involved in the day-to-day running of the company (non-executive or "ordinary" directors) have an affirmative duty to oversee the conduct of those who are, primarily the representative director(s).

This duty derives from the board's overall statutory responsibility to make decisions on business execution and to supervise the performance of duties by directors (as per Article 362, Paragraph 2, Item 2 of the current Companies Act).

The Supreme Court's emphasis that this duty extends beyond matters formally tabled at board meetings is critical. It implies that directors must maintain a general awareness of the company's affairs and cannot simply turn a blind eye to potential problems or misconduct by the RD. The duty includes a proactive element: if they identify concerns, they are expected to take steps to address them, primarily by ensuring the board collectively exercises its oversight. This might involve demanding information, insisting on board meetings, or, in extreme cases, other interventions. - The Irrelevance of Being a "Nominal" Director:

The facts of this case – a company where no formal board meetings were ever held and the RD acted autocratically – are typical of many small or family-owned businesses where directorships can sometimes be "nominal" (名目取締役 - meimoku torishimariyaku), with individuals appointed as directors without any real expectation of active involvement. However, Japanese company law generally does not excuse such nominal directors from their legal duties and potential liabilities. A subsequent Supreme Court decision in 1980 explicitly confirmed that even individuals who agree to become directors merely in name still bear the legal responsibilities of a director, including the duty of supervision. The fact that a company has a history of lax governance or fails to hold proper board meetings does not diminish this underlying duty. - Content of the Supervisory Duty:

The supervisory duty can be broken down into two main components:- Duty to Monitor and Investigate: Directors are expected to keep themselves generally informed about the company's business and financial condition. If circumstances arise that cast doubt on the propriety or legality of the RD's actions, they have a duty to make inquiries and investigate further. In smaller companies where directors might be closer to the daily operations or have easier access to information, the expectation to detect issues might be higher. For outside directors in large, complex organizations, proving a breach of this duty for failing to uncover a well-concealed fraud might be more difficult, unless there were clear "red flags" that should have alerted them.

- Duty to Take Corrective Action: If monitoring or investigation reveals misconduct or serious problems, directors have a duty to take appropriate steps to rectify the situation. The primary mechanism for this is action through the board of directors, such as formally admonishing the RD, curtailing their powers, or, as a last resort, dismissing them from the position of RD (a power of the board under Article 362, Paragraph 2, Item 3 of the Companies Act). In situations where there is an imminent risk of significant harm to the company, directors may also have a duty to notify shareholders or the company's statutory auditor(s) so that those parties can consider exercising their own powers, such as seeking an injunction to stop illegal acts by directors (under Articles 360 or 385 of the Companies Act).

- Standard of Fault: "Gross Negligence":

Under Article 429, Paragraph 1, directors are liable to third parties if their breach of duty to the company was committed with "bad faith or gross negligence." This case demonstrates that a complete failure by ordinary directors to establish any semblance of oversight over a dominant RD, especially in a company with no functioning board process or internal controls, can indeed be found to constitute gross negligence.

Historically, courts were sometimes perceived as being somewhat lenient in finding gross negligence for supervisory failures, particularly in cases involving nominal directors in small, family-run companies. This leniency might have stemmed from a recognition of the practical realities in such enterprises, where the legal minimum of three directors (under the old Commercial Code for companies with a board) often led to the appointment of family members or junior employees who were not genuinely expected to exercise independent oversight. However, this Supreme Court case clearly affirmed that the legal duty exists and a severe dereliction can lead to liability. - Relevance under the Current Companies Act:

The principles laid down in this judgment remain highly relevant under the current Companies Act. While the Act offers more flexibility in corporate structures (e.g., allowing for companies with only one or two directors if no board is established under Article 326), if a company does choose to have a board of directors (which still requires a minimum of three directors under Article 331, Paragraph 5), the supervisory duties of each board member, as articulated by the Supreme Court, persist. In non-board companies, where each director may have rights to execute business and represent the company, a mutual duty of oversight would still be an integral part of their general duty of care to the company.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's May 22, 1973, decision serves as a crucial reminder that the role of a company director in Japan, even a non-representative director, is not a passive or honorary one. Directors have a substantive and proactive duty to supervise the company's business execution, particularly the actions of the representative director. This oversight obligation extends beyond merely attending and voting at board meetings; it requires general vigilance and a willingness to intervene through the board mechanism if necessary to ensure proper and lawful conduct of the company's affairs. A grossly negligent failure in this supervisory duty that leads to harm to third parties can result in the personal liability of those directors to the injured third parties. This case powerfully illustrates that directors cannot simply abdicate their responsibilities, even in the challenging environment of a small or informally run company dominated by a single individual.