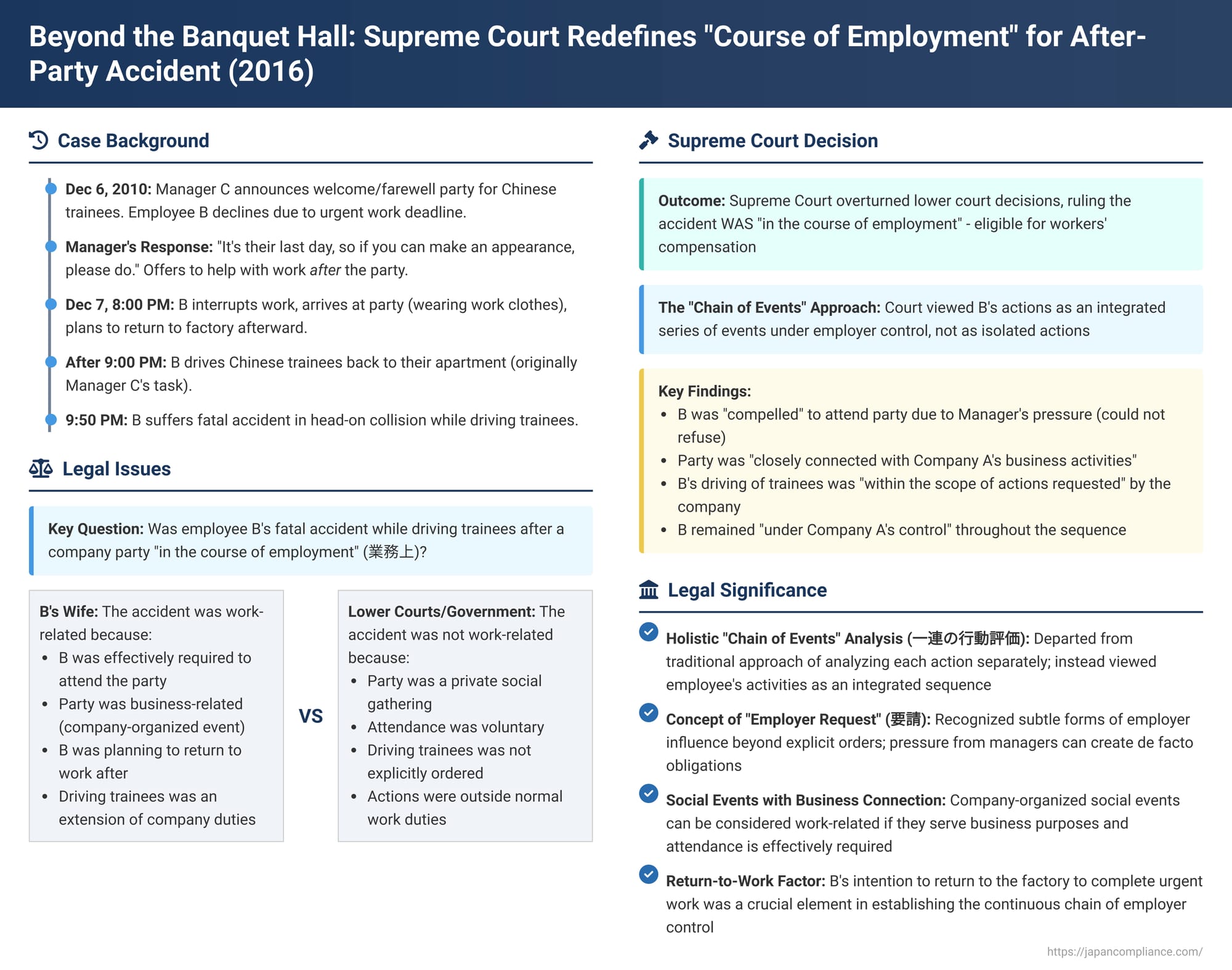

Beyond the Banquet Hall: Supreme Court Redefines "Course of Employment" for After-Party Accident (July 8, 2016)

On July 8, 2016, the Second Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan delivered a significant ruling in a workers' compensation case, often referred to by commentators as the "Teikuro Kyushu Case". This decision revisited the criteria for determining whether an accident occurs "in the course of employment" (業務上 - gyōmujō), particularly in scenarios involving company-organized social events and an employee's subsequent travel. The Court's adoption of a "chain of events" perspective, rather than analyzing each action in isolation, marks an important development in how such cases may be assessed.

The Fateful Evening: A Work Interruption, a Company Party, and a Tragic Accident

The case concerned Employee B, who worked in sales planning for Company A and was on secondment from its Parent Company. Company A was a small firm with seven employees, including B. Due to the frequent absence of Company A's official president (who also held a senior role at the Parent Company), Manager C, Company A's Production Department head, effectively acted as the company's president.

The sequence of events leading to B's fatal accident was as follows:

- The Party Invitation and Work Deadline: On December 6, 2010, Manager C announced plans for a welcome and farewell party to be held the following evening (December 7) for five Chinese trainees hosted by Company A. These trainees were from the Parent Company's subsidiary in China. All Company A employees were invited. Employee B initially declined the invitation, explaining that an important sales strategy document (the Document) was due for submission to President D on December 8 and required completion.

- Manager C's Persuasion: Upon hearing B's reason for declining, Manager C responded, "It's their last day (for some of the trainees), so if you can make an appearance, please do". Manager C further stated that if the Document was not finished by the time of the party, C would personally assist B in completing it after the party concluded. No extension to the Document's deadline was offered.

- The Party and B's Participation: The party commenced around 6:30 PM on December 7 at a local restaurant (the Restaurant) without waiting for B, who was still at the Factory working on the Document. All other Company A employees and the five trainees attended. Manager C had arranged to use a company car to transport the trainees from their apartment (the Apartment) to the Restaurant and had planned to drive them back after the event.

After some time, B temporarily suspended work on the Document, and still wearing work clothes, drove a company car (the Vehicle) to the Restaurant, arriving around 8:00 PM, approximately 30 minutes before the party's scheduled end time. Upon arrival, B informed Company A's general affairs manager of an intention to return to the Factory after the party to continue working on the Document. The general affairs manager reportedly replied, "Eat your fill and then head straight back". B did not consume any alcohol at the party, despite being offered. - Post-Party Arrangements and the Accident: The party concluded after 9:00 PM, and its cost was covered by Company A as a welfare expense. Employee B then undertook the task of driving the trainees, some of whom were intoxicated, back to the Apartment, intending to proceed to the Factory thereafter to resume work on the Document. While driving the trainees in the Vehicle towards the Apartment, B was involved in a head-on collision with a large truck traveling in the oncoming lane. B suffered fatal head trauma in the accident, which occurred around 9:50 PM. It was noted that both the Factory and the Apartment were located south of the Restaurant, and the distance between the Factory and the Apartment was approximately 2 kilometers.

B's wife, Plaintiff X, subsequently applied for survivors' compensation benefits and funeral expenses under Japan's Workers' Accident Compensation Insurance Act. The local Labor Standards Inspection Office Director denied these claims, ruling that B's death was not work-related. Plaintiff X then initiated legal proceedings against Y (the State) seeking the revocation of this non-payment decision.

Lower Courts: Party and Driving Deemed Private Acts

Both the Tokyo District Court (first instance) and the Tokyo High Court (on appeal) dismissed Plaintiff X's claim. These courts characterized the welcome/farewell party as a private gathering. They concluded that B's decision to attend the party mid-way through, and the subsequent act of voluntarily driving the trainees, were not actions performed under the control of Company A. Therefore, the death was not considered to be in the course of employment. Plaintiff X then appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Reversal: A Holistic "Chain of Events" Analysis

The Supreme Court overturned the lower courts' decisions and revoked the non-payment determination, ultimately ruling that B's death was work-related.

I. The "Under Employer Control" Principle

The Court began by reaffirming the established legal principle for determining work-related disasters under the Workers' Accident Compensation Insurance Act: "For a worker's injury, illness, disability, or death (hereinafter 'disaster') to be eligible for insurance benefits for a work-related disaster... it must be due to causes 'in the course of employment.' One of the requirements for this is that the disaster occurred while the worker was under the control of the employer based on the labor contract". This is often referred to as the "work performance nature" (業務遂行性 - gyōmu suikōsei) requirement.

II. Applying the Principle to B's Circumstances: The "Chain of Events"

The Supreme Court then meticulously analyzed the specific facts, focusing on the sequence of events leading to the accident:

- Compelled Attendance and Return to Work: The Court found that B's decision to interrupt work on the critical Document, attend the party, and then return to the Factory was not purely voluntary. Manager C, acting as Company A's de facto president, had strongly indicated a desire for B to attend the party, even after B cited the urgent work deadline. Crucially, no extension was offered for the Document; instead, Manager C proposed to help B complete it after the party. The Supreme Court reasoned: "Thus, B was placed in a situation where B could not refuse to attend the party due to Manager C's above-mentioned intentions, and as a result, was compelled to return to the Factory to resume the said work after the party ended. From Company A's perspective, this can be said to be a request for B to undertake this series of actions in the course of B's duties".

- Party's Connection to Business Activities: The Court determined that the welcome/farewell party was not merely a private social event. It was "part of an event planned by Company A to achieve training objectives" and, by fostering camaraderie between the Chinese trainees and Company A's employees, it served to "contribute to the strengthening of relations between Company A, the Parent Company, and the said Chinese subsidiary". Therefore, the party was "conducted in close connection with Company A's business activities".

- Driving Trainees as Part of the Requested Actions: Employee B's act of driving the trainees to their Apartment (a task originally planned to be done by Manager C) was also viewed within this continuous chain of events. The Court noted that the route from the Restaurant to the Apartment did not significantly deviate from B's route back to the Factory to resume work. Therefore, B driving the trainees was considered "within the scope of the series of actions requested by Company A".

III. Overall Assessment: B Remained Under Employer Control

Synthesizing these elements, the Supreme Court concluded: "B was placed in a situation by Company A where B could not refuse to attend the party, which was closely related to its business activities. B temporarily interrupted work at the Factory to participate mid-way and, upon the party's conclusion, was in the process of driving the Vehicle to return to the Factory to resume work, and concurrently, was driving the trainees to their Apartment on behalf of Manager C when the accident occurred".

"Therefore, even considering that the party was held off-site from the workplace, alcohol was served (though not consumed by B), and driving the trainees to their Apartment was not based on an explicit instruction from Manager C or others, B should be considered to have still been under Company A's control at the time of the accident".

The Court also affirmed that a "considerable causal relationship" existed between B's driving actions and the fatal accident.

Deeper Significance: The "Chain of Events" and "Employer Request"

This Supreme Court decision is noteworthy not for laying down broad new legal doctrines but for its specific method of factual analysis in a complex "work performance nature" case.

- Holistic Evaluation (「一連の行動」評価 - ichiren no kōdō hyōka): The most striking aspect of the judgment is its departure from the approach of the lower courts and, often, administrative practice, which tends to dissect an employee's actions into discrete segments and evaluate the work-relatedness of each part separately. The Supreme Court, instead, adopted what the commentary calls a "holistic evaluation of a series of events" (一連事情一括評価方式 - ichiren jijō ikkatsu hyōka hōshiki). It viewed B's actions—interrupting urgent work, attending the party under managerial pressure, and then driving the trainees while en route back to resume work—as an integrated "series of actions". This approach allowed the Court to see the connection between these actions and the underlying business purpose and employer influence.

- The Nuance of "Request" (「要請」- yōsei): The judgment repeatedly uses the term "requested" (要請された - yōsei sareta) to describe Company A's influence over B's actions. The commentary suggests this wording was likely chosen carefully. Attending a social party, even one with business undertones, is not typically a task an employer can formally "order" or "instruct" an employee to do in the same way as core job duties. "Request" captures the strong managerial expectation and inducement that effectively left B with little choice but to comply, particularly given Manager C's de facto presidential role and offer to assist with the urgent work after the party.

Scope, Challenges, and Implications

While the Supreme Court's approach provides a more flexible and substance-oriented framework for assessing such cases, it also presents challenges.

- Defining "Request" and "Chain of Events": The criteria of an employer "request" and what constitutes an unbroken "chain of events" under employer control are somewhat general. Future application will require careful development to ensure consistent and fair outcomes in workers' compensation certifications.

- The "Return to Resume Work" Factor: The commentary emphasizes that B's intent to return to the Factory to resume an interrupted core work task was a crucial element in this case. The ruling's scope (射程 - shatei) might therefore be limited and may not necessarily extend to situations where an employee is, for example, involved in an accident while traveling directly home after a company social event. Such a scenario might fall under commuting accident provisions, if at all, rather than a work-related disaster during the course of employment.

- Administrative Practice vs. Judicial Precedent: This decision, particularly its "chain of events" evaluation method, represents a departure from the more segmented analysis often used in initial administrative determinations of workers' compensation claims. It signals a willingness by the judiciary to look more holistically at the context surrounding accidents connected to work-related activities.

Conclusion: A More Integrated View of Work-Relatedness

The Supreme Court's ruling in the Company A (Teikuro Kyushu) case offers a nuanced perspective on determining whether an accident occurs "in the course of employment." By focusing on the entire "chain of events" and the substantive nature of the employer's "request" or inducement, the Court found that an employee, even while attending an off-site social function and undertaking related travel, could remain under the employer's control. This was especially so when the social event was closely tied to business objectives and the employee's participation was effectively compelled, leading to an interruption of, and an intention to return to, core work duties. The decision emphasizes that a formalistic separation of actions might obscure the underlying reality of employer control and business connection, paving the way for a more integrated and substantive assessment in complex workers' compensation cases.