Beyond the Balance Sheet: Japanese Supreme Court Redefines 'Bad Debt Loss' in Landmark Jusen Crisis Case

Date of Judgment: December 24, 2004

Case Name: Corporate Tax Reassessment Invalidation Lawsuit (平成14年(行ヒ)第147号)

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench

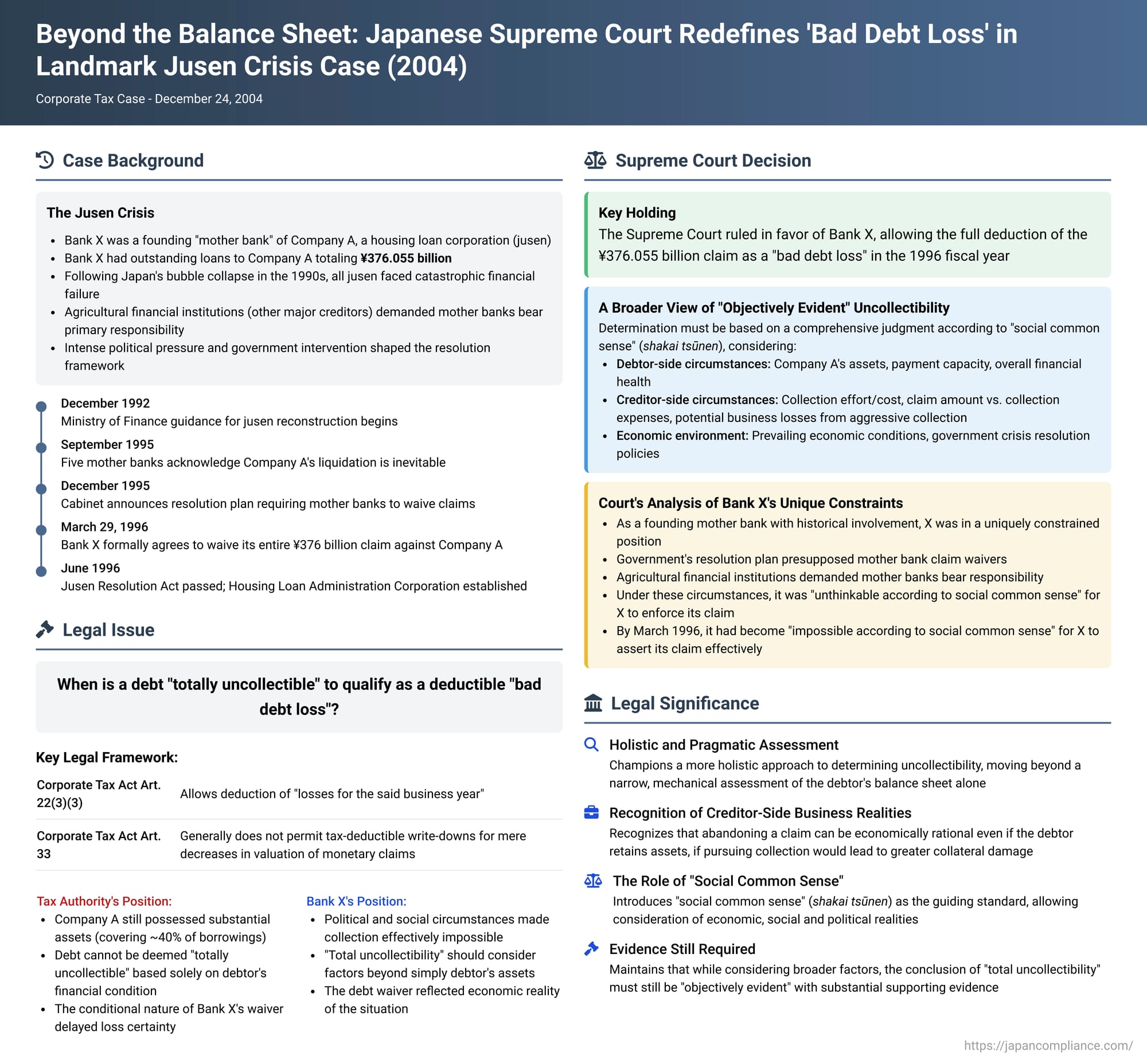

In a highly significant judgment delivered on December 24, 2004, arising from the tumultuous collapse of Japan's jusen (housing loan corporations) in the 1990s, the Supreme Court of Japan provided a critical reinterpretation of what constitutes a deductible "bad debt loss" (貸倒損失 - kashidaore sonshitsu) for corporate income tax purposes. The case, often referred to as the "Kogin case" or "IBJ (Industrial Bank of Japan) case" due to the appellant bank's predecessor, centered on whether a bank could claim a massive loan waiver to a failing jusen as a bad debt loss, and crucially, how the "total uncollectibility" of such a debt should be assessed. The Court's decision marked a shift towards a more comprehensive and pragmatic approach, considering not only the debtor's financial state but also the creditor's circumstances and the broader socio-economic environment.

The Jusen Quagmire: A Bank's Costly Dilemma

The appellant was Bank X (the successor to the original creditor bank, referred to as B-Bank in the judgment text), a major Japanese financial institution. The debtor was Company A, one of several jusen—specialized housing loan corporations that had financed aggressive real estate lending during Japan's "bubble economy" of the late 1980s and subsequently faced catastrophic failure in the early 1990s.

Key facts setting the stage for the legal dispute include:

- Bank X's Deep Involvement: X was a founding "mother bank" (botai ginko) of Company A, playing a significant role in its establishment, management, and funding. X had outstanding loans to A totaling a staggering ¥376.055 billion ("the subject claim").

- The Jusen Crisis and Government Intervention: Following the collapse of the bubble economy, the financial health of all jusen, including A, deteriorated rapidly. By December 1992, the Ministry of Finance was guiding the jusen towards reconstruction plans involving interest rate concessions from lending institutions. Agricultural financial institutions (major non-mother bank creditors of the jusen) initially resisted these plans but agreed to cooperate on the condition that the mother banks take primary responsibility for the reconstruction and that their own principal repayments would be secured.

- Failed Reconstruction and Liquidation Policy: Despite these efforts, the real estate market continued its decline, and by September 1995, A's five mother banks, including X, acknowledged that A's liquidation was inevitable. This led to intense negotiations and public debate over the extent of the mother banks' financial responsibility for the massive losses.

- Pressure for Mother Banks to Bear Losses: Agricultural financial institutions, in particular, strongly argued for "complete mother bank responsibility," meaning mother banks should cover not only their own losses but also ensure the agricultural institutions' loan principals were repaid. Bank X, while accepting some responsibility (termed "modified mother bank responsibility," essentially agreeing to waive its own claims), resisted covering losses beyond that, citing limitations under company law. The Ministry of Finance had previously given assurances to the agricultural institutions that their interests would be protected, placing mother banks like X in a difficult position.

- Government Resolution Plan: In December 1995, the Japanese Cabinet announced a formal plan to address the jusen crisis, involving the establishment of a resolution entity (later the Housing Loan Administration Corporation) and the injection of public funds. This plan implicitly and then explicitly confirmed that mother banks would be expected to waive their entire claims against the failing jusen. Subsequent legislation, the Jusen Resolution Act, was passed in June 1996 to implement this.

- Bank X's Claim Waiver and Tax Deduction: Faced with insufficient bad debt reserves and anticipating enormous losses, and also needing to offset these losses against taxable income, Bank X actively sold appreciated stocks between November 1995 and March 1996, generating significant capital gains. On March 29, 1996, within its fiscal year ending March 31, 1996 ("the subject fiscal year"), X formally agreed with Company A to waive its entire ¥376 billion claim. This waiver was subject to a resolutive condition: it would become void if A's business transfer to the resolution entity and its legal dissolution were not completed by December 31, 1996 (these events did occur by September 1996 ). X then deducted the full amount of this waived claim as a bad debt loss in its corporate tax return for the subject fiscal year.

- Tax Office Denial: The tax authorities (Y) denied this deduction, leading to a significant tax reassessment and penalties, which X (as successor to B-Bank) challenged in court.

The Legal Sticking Point: When is a Debt "Totally Uncollectible"?

The core legal issue revolved around the interpretation of Article 22, paragraph 3, item 3 of the Corporate Tax Act, which allows for the deduction of "losses for the said business year". For monetary claims, such a loss is typically recognized when the debt becomes a "bad debt".

It is generally accepted in Japanese tax law that for a bad debt loss to be deductible, the entire amount of the monetary claim must be uncollectible. This is partly because Article 33 of the Corporate Tax Act generally does not permit tax-deductible write-downs for mere decreases in the valuation of monetary claims (unlike some other assets); a full write-off requires demonstrating uncollectibility.

The High Court, in ruling against X, had focused primarily on Company A's objective financial condition as of March 1996. It found that A still possessed substantial assets (estimated to cover about 40% of its total borrowings), and therefore, X's claim could not be deemed "totally uncollectible" from A's perspective alone at that time. The High Court also considered the conditional nature of X's waiver as a factor that might delay the certainty of the loss.

The Supreme Court's Broader View of "Objectively Evident" Uncollectibility

The Supreme Court overturned the High Court's decision and ruled in favor of Bank X, permitting the deduction of the bad debt loss in the subject fiscal year. The Court agreed that "total uncollectibility" of the full claim was a prerequisite for the deduction and that this uncollectibility must be "objectively evident" (kyakkanteki ni akiraka).

However, the Supreme Court significantly expanded the lens through which "objectively evident" total uncollectibility should be assessed. It held that this determination must be made based on a comprehensive judgment according to "social common sense" (shakai tsūnen), taking into account not only the debtor's situation but also a range of other pertinent factors.

The Court laid out the following comprehensive set of considerations:

- Debtor-side circumstances: The debtor's (Company A's) asset situation, payment capacity, and overall financial health.

- Creditor-side circumstances: The effort and cost required for the creditor (Bank X) to attempt collection, a comparison of the claim amount versus potential collection expenses, and potential broader business losses that the creditor might suffer from pursuing aggressive collection (e.g., damage to reputation, conflict with other significant creditors or stakeholders).

- Economic environment and other relevant factors: The prevailing economic conditions, and specific contextual elements like the government's crisis resolution policies.

Applying this broader framework to the facts of X's claim against A, the Supreme Court reasoned:

- X's Constrained Position: As a founding mother bank with deep historical involvement in A, and having previously benefited from certain repayment priorities in earlier failed reconstruction plans for A, X was in a uniquely constrained position. The agricultural financial institutions, which were also major creditors of A and significant institutional investors in X's own bank debentures, were adamant that mother banks bear the brunt of the jusen losses.

- Political and Social Unfeasibility of Collection: Given the government's publicly announced resolution plan (which presupposed mother bank claim waivers and prioritized non-mother bank claims to a certain extent), the strong stance of the agricultural co-ops, and the immense public and political pressure surrounding the jusen crisis, it was "unthinkable according to social common sense" for X to attempt to enforce its claim against A on an equal loss-sharing basis with (or certainly ahead of) the agricultural institutions by March 1996. Such an attempt would have invited severe social criticism and risked substantial business repercussions for X.

- Economic Reality of A's Assets: Under the government's resolution plan, A's estimated recoverable assets were insufficient to cover the claims of non-mother financial institutions in full, let alone any portion of X's claim. Had A been forced into a standard bankruptcy proceeding instead, the recovery prospects would likely have been even worse given the depressed real estate market at the time.

- Conclusion on Uncollectibility: Therefore, the Supreme Court concluded that by the end of March 1996, it had become "impossible according to social common sense" for X to assert its claim against A effectively. Considering A's asset situation within this inescapable broader context, the total uncollectibility of X's ¥376 billion claim was "objectively evident" as of that date. The fact that X's waiver was subject to a resolutive condition (which was ultimately met) did not alter this assessment of objective uncollectibility at that specific point in time.

Implications of the "Social Common Sense" Standard

The Supreme Court's decision in the Kogin case has had lasting implications for the understanding of bad debt losses in Japanese tax law:

- Holistic and Pragmatic Assessment: The ruling champions a more holistic and pragmatic approach to determining uncollectibility, moving beyond a narrow, mechanical assessment of the debtor's balance sheet alone. It acknowledges that the true economic collectibility of a debt can be profoundly affected by the creditor's specific circumstances and the overarching environment.

- Recognition of Creditor-Side Business Realities: The decision gives significant weight to the business realities faced by the creditor. It recognizes that a decision to abandon a claim can be an economically rational and objectively justifiable business judgment, even if the debtor is not entirely devoid of assets, if pursuing the claim would lead to greater collateral damage or is practically unfeasible due to external pressures.

- The Role of "Social Common Sense" (Shakai Tsūnen): The introduction of "social common sense" as the guiding standard implies a case-by-case evaluation by the courts, allowing for flexibility in considering a wide array of relevant facts and circumstances. It seeks to align tax treatment with reasonable business behavior in extraordinary situations.

- Importance of Objective Evidence: While broadening the scope of relevant factors to include creditor-side considerations (which might seem subjective), the Supreme Court maintained the requirement that the conclusion of "total uncollectibility" must still be "objectively evident". This means that all factors, including the creditor's circumstances and the environmental pressures, must be substantiated by objective evidence, not merely based on the taxpayer's subjective beliefs or undocumented fears. The High Court had reportedly hesitated to broadly consider creditor-side factors due to concerns about potential taxpayer manipulation of loss timing; the Supreme Court's approach suggests that the need for objective evidence can mitigate this concern.

- Timing of Loss Recognition: The judgment implicitly reinforces the principle that a bad debt loss should be recognized for tax purposes in the specific business year when its total uncollectibility becomes objectively evident. Taxpayers do not have unfettered discretion to choose the timing of such deductions for profit manipulation purposes.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 2004 judgment in the Kogin jusen case represents a landmark in Japanese corporate tax law concerning bad debt losses. It established a more comprehensive and context-sensitive framework for assessing the "total uncollectibility" of a debt, mandating consideration of not only the debtor's financial status but also the creditor's unique business circumstances and the prevailing economic, social, and even political environment. By anchoring this multifaceted assessment in the standard of "social common sense" and the requirement for "objectively evident" proof, the Court sought to balance the need for a realistic approach to business losses with the imperative of preventing arbitrary or manipulative tax deductions. This ruling continues to be a vital reference for businesses navigating the complexities of debt recovery and loss recognition in challenging circumstances.