Beyond Repair: Japan's Supreme Court on Rebuilding Costs for Severely Defective New Homes

Judgment Date: September 24, 2002

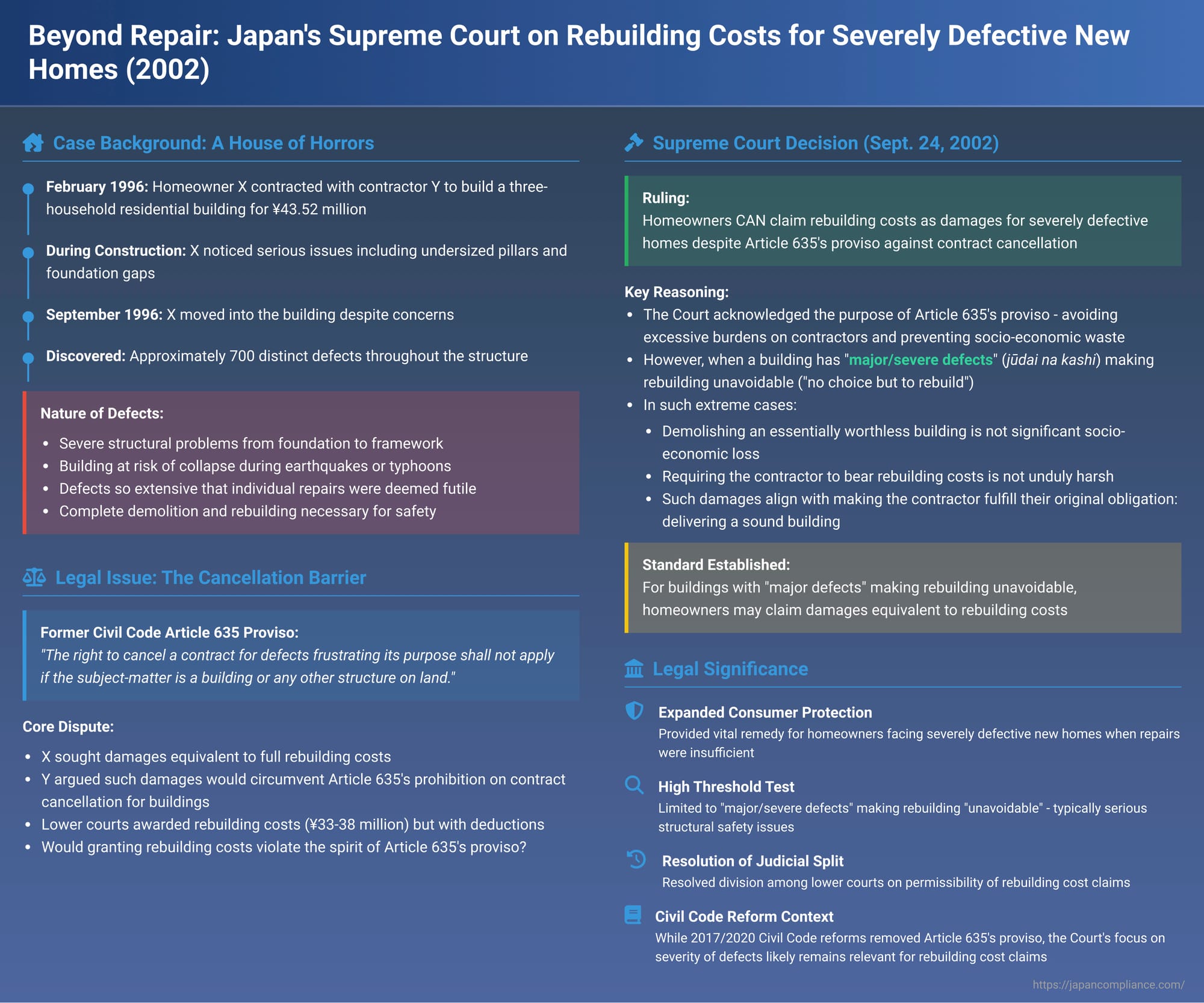

Imagine the distress of moving into a newly constructed home, only to discover that it is riddled with so many severe defects that mere repairs are insufficient, and the entire structure needs to be demolished and rebuilt. This nightmare scenario was the subject of a landmark Japanese Supreme Court decision on September 24, 2002 (Heisei 14 (Ju) No. 605). The case centered on whether a homeowner, X, could claim damages from the construction contractor, Y, equivalent to the full cost of rebuilding the house, particularly in light of a provision in Japan's former Civil Code that restricted the right to cancel contracts for defective buildings.

A Homeowner's Ordeal: A Litany of Defects

In February 1996, X (the plaintiff homeowner) entered into a contract with Y (the defendant contractor) for the construction of a three-household residential building ("the Building"). The agreed price was approximately ¥43.52 million, with a scheduled completion and handover date of August 31, 1996.

Problems emerged even during the construction phase. X observed issues such as the use of undersized pillars and significant gaps in the foundation, prompting repeated requests for rectification. Despite these concerns, X moved into the Building on September 28, 1996. It soon became apparent that the Building suffered from an extremely large number of defects—the first instance court noted around 700 distinct issues.

Crucially, these were not minor cosmetic flaws. The defects were systemic and severe, affecting the entire structural integrity of the Building, from the foundation and sills to the pillars and overall framework. The courts found that these defects critically compromised the Building's safety and durability to such an extent that individual, piecemeal repairs would be futile. The structure was deemed to be at risk of collapse from events like earthquakes or typhoons. The only viable solution was to completely demolish the existing defective structure and rebuild it from scratch.

The Legal Conundrum: Contract Cancellation vs. Damages for Rebuilding Under the Former Civil Code

The primary legal hurdle in this case was a specific provision in Japan's Civil Code as it stood before the major reforms of 2017 (which came into effect in 2020). Article 635 of the former Civil Code dealt with a client's right to cancel a contract for completed work if there were defects in the work that frustrated the purpose of the contract. However, a critical proviso to this article stated: "this shall not apply if the subject-matter of the contract is a building or any other structure on land."

The rationale behind this proviso was to prevent what was seen as potentially excessive hardship for contractors and significant socio-economic waste. If a contract for a completed building could be easily cancelled for defects, the contractor might be forced to demolish a structure that, despite its flaws, might still possess some utility or value. This was generally understood as a mandatory provision, strictly limiting the remedy of contract cancellation for defective buildings.

Y, the contractor, argued that X's claim for damages equivalent to the full cost of rebuilding the house was, in substance, an attempt to achieve the same outcome as contract cancellation. Therefore, Y contended, allowing such a damage claim would contravene the spirit and purpose of the Article 635 proviso.

The lower courts, however, had sided with X on the necessity of rebuilding. The Yokohama District Court (Odawara Branch) found that the defects were so extensive that individual repairs were impossible and rebuilding was necessary. It awarded X approximately ¥33.28 million in damages (after deducting unpaid portions of the original contract price). The Tokyo High Court affirmed the necessity of rebuilding and assessed the rebuilding cost at ¥38.302 million. However, the High Court controversially deducted ¥6 million from this amount, deeming it the "benefit" X had received from living in the (albeit defective) Building for a period. After also deducting the unpaid contract price, it awarded X damages of approximately ¥25.58 million. Y appealed to the Supreme Court, specifically challenging the permissibility of awarding rebuilding costs as damages.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Ruling: Rebuilding Costs as Legitimate Damages

The Supreme Court dismissed Y's appeal, thereby upholding X's right to claim damages equivalent to the cost of rebuilding the severely defective house. The Court's reasoning carefully distinguished this type of damage claim from the contract cancellation prohibited by the former Article 635 proviso:

- Acknowledging the Purpose of the Proviso: The Supreme Court began by acknowledging the traditional rationale behind the Article 635 proviso: to avoid imposing excessive burdens on contractors and preventing the socio-economic loss that would result from demolishing a potentially still valuable or usable, albeit defective, structure.

- Distinguishing Severely Defective Buildings: The Court then drew a critical distinction. The situation is different, it argued, when a contractor constructs a building with "major/severe defects" (重大な瑕疵 - jūdai na kashi) to such an extent that there is realistically "no choice but to rebuild it" (建て替えるほかはない場合 - tatekaeru hoka wa nai baai). In such extreme cases:

- Demolishing such a fundamentally flawed, unsafe, and essentially worthless building does not constitute a significant socio-economic loss. The premise of the proviso – protecting a structure with residual utility – does not apply.

- Requiring the contractor to bear the cost of rebuilding is not an unduly "harsh" or "excessive" burden. Instead, it is a means of holding the contractor accountable for their failure to fulfill their primary contractual obligation: to deliver a sound, non-defective building. Awarding damages equivalent to rebuilding costs, in this context, aligns with the principle of making the contractor liable for damages that effectively achieve the performance promised under the contract.

- Conclusion on the Proviso: Based on this distinction, the Supreme Court concluded that allowing a homeowner to claim damages equivalent to the cost of rebuilding a building with such severe and fundamental defects does not contravene the spirit or purpose of the former Civil Code Article 635 proviso.

- General Rule Established: The Court thus established a clear rule: if the object of a construction contract (a building) suffers from major defects that are so severe as to make its rebuilding unavoidable, the client (homeowner) is entitled to claim damages from the contractor equivalent to the cost of such rebuilding.

Analyzing the Decision and Its Context

This 2002 Supreme Court ruling was a landmark decision in Japanese construction law and consumer protection:

- Addressing the "Defective Housing" Problem: It provided a significant remedy for homeowners victimized by shoddy construction practices where simple repairs would be inadequate. It acknowledged that in some cases, nothing short of a complete rebuild can rectify the contractor's failure.

- Defining "Major Defects" and "Necessity to Rebuild": The standard set by the Court is high. The right to claim rebuilding costs is not for minor or easily repairable defects. The judgment consistently refers to "major/severe defects" and situations where one "has no choice but to rebuild." Legal commentary has since debated whether this "necessity" is limited to physical impossibility of repair or could extend to situations of economic impossibility (e.g., where the cost of repairs would far exceed the cost of rebuilding). The Supreme Court's language in this case strongly implies a focus on fundamental structural failures that render the building unsafe or unfit for its intended purpose.

- Interaction with Contract Cancellation Rules (Under Former Law): The Court cleverly allowed a remedy that achieved a similar economic outcome to contract cancellation (i.e., the client effectively gets a new, non-defective building at the contractor's expense) without directly contravening the statutory prohibition on formally cancelling the contract for a land structure. It did so by framing the rebuilding cost as a measure of damages for breach of the contractor's performance obligation (or warranty against defects).

- Resolving Pre-existing Legal Uncertainty: Prior to this ruling, lower courts in Japan had been divided on whether to allow claims for rebuilding costs. Some denied such claims, viewing them as a backdoor to contract cancellation or as leading to unjust enrichment for the homeowner (who would receive a brand-new building). Others had allowed them, particularly where defects were extreme. The Supreme Court's decision provided much-needed clarity and authoritative guidance.

The Impact of the 2017 Civil Code Reforms (Effective April 2020)

It is crucial to understand this Supreme Court judgment in its historical legal context, as Japan's Civil Code underwent major revisions in 2017, which came into force in April 2020. These reforms significantly changed the legal framework for contractual liability, including defect warranties in construction contracts:

- Abolition of Former Article 635 and Related Defect Warranty Provisions: The specific articles of the former Civil Code dealing with a contractor's warranty against defects (瑕疵担保責任 - kashi tanpo sekinin), including Article 634 (client's rights to demand repair or damages) and Article 635 (client's right to cancel, and its proviso for land structures), were deleted.

- Governance by General Non-Performance Rules: Liability for defects in construction contracts is now primarily governed by the general Civil Code rules pertaining to non-performance of contractual obligations (債務不履行 - saimu furikō). This means the client's remedies are now aligned with general contract law, including the right to demand completion of performance (which can include repair of defects), claim a price reduction if performance is incomplete or defective, claim damages, and, importantly, cancel the contract if the non-performance is material (subject to general contract cancellation rules in Civil Code Arts. 541, 542, etc.).

- No More Specific Statutory Bar on Cancelling Building Contracts for Defects: The most direct change relevant to this Supreme Court case is that the specific prohibition in the former Article 635 proviso against cancelling contracts for defective land structures no longer exists in the new Civil Code. This means that, in principle, contract cancellation is now a legally available remedy for homeowners even if the defective work is a completed building, provided the general conditions for contract cancellation (e.g., material breach, failure to cure after demand) are met.

Continuing Relevance of the Supreme Court's Underlying Rationale?

While the direct statutory conflict (claiming rebuilding costs vs. the bar on cancellation) that the 2002 Supreme Court judgment navigated has been removed by the Civil Code reforms, the underlying principles discussed by the Court may still hold relevance. The Court's emphasis on the severity of defects ("major defects," "no choice but to rebuild") as a precondition for such a drastic remedy as awarding full rebuilding costs, and its considerations of socio-economic loss and undue hardship on the contractor, are fundamental equitable concerns.

Under the new Civil Code, while cancellation is theoretically possible, courts will still need to determine the appropriateness of specific remedies. Demanding the complete rebuilding of a structure (whether as a claim for damages to fund it, or as a form of specific performance to rectify non-conforming work) is an extreme remedy. It is likely that courts will continue to require a very high threshold of severity and irrepairability of defects – similar to the "major defects necessitating rebuilding" standard articulated in this 2002 Supreme Court judgment – before granting such extensive relief, even under the revised legal framework. The concerns about avoiding disproportionate burdens and socio-economic waste remain valid considerations in shaping the application of general contract remedies to specific construction defect scenarios.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's September 2002 decision was a landmark ruling under Japan's former Civil Code, providing crucial protection for homeowners faced with newly constructed dwellings suffering from severe, irreparable defects. By affirming the right to claim damages equivalent to the cost of rebuilding, the Court ensured that clients were not left without an adequate remedy simply because the defective item was a building. While the specific statutory landscape has since changed with the 2017 Civil Code reforms, which removed the old bar on cancelling building contracts for defects, the judgment's underlying emphasis on the substantiality of the defects and the pursuit of a fair and practical outcome for the aggrieved party continues to resonate and may well inform how courts approach similar cases under the new legal regime.