Beyond Marriage and Engagement: A 2004 Japanese Supreme Court Ruling on the Breakup of "Partnership Relationships" and Liability

Date of Judgment: November 18, 2004

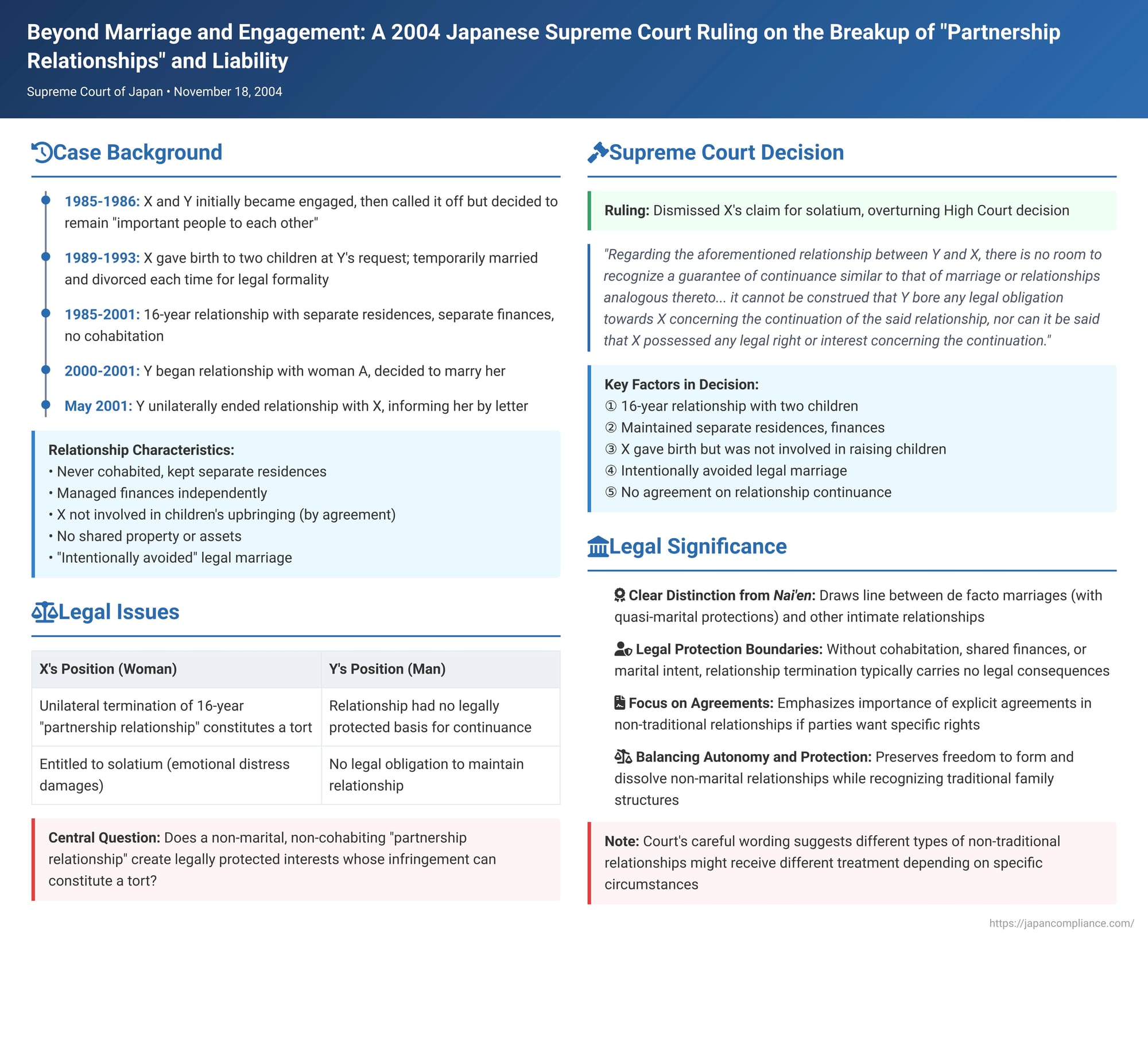

Japanese family law has well-established principles for dealing with the dissolution of formal marriages (legal unions registered under the Civil Code) and, to a significant extent, nai'en (内縁) or de facto marital relationships, which are often treated as quasi-marriages. But what happens when a long-term, intimate relationship between a man and a woman does not fit neatly into either of these categories? If the parties consciously chose not to marry or cohabit in a traditional sense, yet maintained a significant, long-standing connection that included having children, can one party claim damages for emotional distress if the other unilaterally ends this "partnership relationship"? The Supreme Court of Japan confronted this novel question in a decision on November 18, 2004 (Heisei 15 (Ju) No. 1943).

The Facts: A Long-Term Relationship Outside Traditional Bounds

The case involved a woman, X, and a man, Y. Their relationship began in November 1985. A month later, they became engaged, but this formal engagement was dissolved by March of the following year (1986). At that time, they sent a joint letter to acquaintances stating that while their engagement was off, "there is no change in the fact that we are important people to each other, and therefore... we have decided to deepen our friendly relations as special individuals to one another."

Following this, X and Y continued their relationship for approximately 16 years, until May 2001. During this extended period:

- They maintained separate residences and never cohabited in the traditional sense of sharing a household.

- They managed their finances independently and had no jointly owned property.

- At Y's request, X gave birth to two children: a daughter in June 1989 and a son in February 1993.

- By prior agreement between X and Y, X was not involved in the upbringing of the children. The daughter was raised by Y's mother, and the son, after initially being with Y, was placed in an institutional facility. X received considerable sums from Y or his family to cover childbirth expenses on both occasions.

- At the time of each child's birth, X and Y would temporarily register a legal marriage, only to register a divorce by agreement shortly thereafter. This was done, according to the findings, out of consideration to prevent the children from suffering legal disadvantages (e.g., by ensuring they were born as legitimate children within a registered marriage). Critically, the Court found that after the formal engagement was dissolved in March 1986, there was never a mutual intent between X and Y to enter into a legal marriage as defined by the Civil Code; rather, they intentionally avoided it.

- During their long relationship, they sometimes collaborated on work matters and occasionally traveled together.

- There was no evidence of any agreement between X and Y that one party could not unilaterally end the relationship or marry someone else without the other's consent.

Around 2000, Y began a relationship with another woman, A, who was a part-time employee at his workplace. By April 30, 2001, Y and A had decided to marry. On May 2, 2001, Y met X at a train station, handed her a letter stating that he could no longer continue their relationship as before, informed her of his intention to marry another woman, and thus unilaterally ended his relationship with X. Y and A registered their marriage on July 18, 2001, and in March 2002, Y took custody of his son (previously in the institution) to raise him with A.

X subsequently sued Y for solatium (damages for emotional distress), arguing that Y's sudden and unilateral termination of their long-standing "partnership relationship" constituted a tort.

The Lower Courts' Differing Views

The first instance court dismissed X's claim.

The appellate court (High Court), however, took a different view and ordered Y to pay X 1 million yen in solatium. The High Court acknowledged that X and Y's relationship was one where its maintenance was "entrusted solely to the free will of both parties" and was "not accompanied by legal binding force," suggesting that its dissolution might not typically give rise to damages. However, it emphasized that X and Y had maintained their relationship for about 16 years, had two children, sometimes cooperated in work, and traveled together, thus maintaining a status as "special individuals" to each other. The High Court found that Y's sudden, unilateral termination of this relationship, without particular discussion with X, "unilaterally betrayed X's expectation of the relationship's continuation and cannot be deemed reasonable". This betrayal of expectation was deemed tortious. Y then appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Decision: No Legally Protected Interest in Continuation

The Supreme Court reversed the High Court's decision in favor of Y (the man), and reinstated the first instance judgment dismissing X's claim for solatium.

The Court's Reasoning:

The Supreme Court meticulously reviewed the factual elements of X and Y's relationship:

- Duration and Connection (Point ① in judgment): The relationship spanned approximately 16 years, they had two children, and sometimes cooperated in work and traveled together.

- Lack of Cohabitation and Financial Independence (Point ②): Throughout this period, they maintained separate residences, never cohabited, managed their finances independently, and had no shared property.

- Child-Rearing Arrangement (Point ③): X gave birth to two children at Y's request, but by prior agreement based on X's wish to be free from child-rearing responsibilities, X had no involvement in raising the children. X received substantial payments from Y's side for childbirth expenses.

- Intentional Avoidance of Legal Marriage (Point ④): Although they temporarily registered marriages at the time of the children's births (followed by swift divorces) for the children's legal benefit, there was no mutual intent to enter into a genuine, ongoing legal marriage after their initial engagement was dissolved in 1986. In fact, they "intentionally avoided" legal marriage.

- No Agreement on Relationship Continuance (Point ⑤): There was no evidence of any agreement, explicit or implicit, that one party could not unilaterally end the relationship or marry someone else.

Based on these comprehensive findings, the Supreme Court concluded:

"Considering these various points, regarding the aforementioned relationship between Y and X, there is no room to recognize a guarantee of continuance similar to that of marriage or relationships analogous thereto. Moreover, it cannot be construed that Y bore any legal obligation towards X concerning the continuation of the said relationship, nor can it be said that X possessed any legal right or interest concerning the continuation of the said relationship."

Therefore, even though Y's sudden and unilateral termination of this long-standing relationship might have caused X emotional distress, the Court held: "Y's aforementioned act cannot be evaluated as a tortious act giving rise to a claim for solatium."

The Significance of the Ruling: Defining the Boundaries of Legal Protection for Non-Marital Relationships

This 2004 Supreme Court decision is highly significant for its exploration of the legal status and protection (or lack thereof) afforded to intimate relationships that do not fit the traditional molds of either formal marriage or nai'en (de facto marriage, which often implies cohabitation and an intent to marry or live as spouses).

- Distinction from Nai'en (Quasi-Marriage): Traditional nai'en jurisprudence in Japan has extended many protections analogous to legal marriage to couples who cohabit and share a life with the mutual understanding that they are, in substance, husband and wife, even without formal registration. A key element often considered is the "intent to marry" or at least an "intent to conduct a communal marital life." This Supreme Court decision explicitly found that X and Y's relationship lacked these characteristics—they intentionally avoided marriage and did not cohabit or share finances. Therefore, the protections typically afforded to nai'en relationships (such as damages for unjust repudiation, often based on an analogy to breaking a marriage engagement or as a tort infringing the quasi-marital protected interest) were not applicable here.

- No General "Right to Relationship Continuance" in This Context: The Court found no legal basis for X to have a protected expectation that this specific type of "special individual" relationship would continue indefinitely or could not be unilaterally terminated by Y without legal consequence, especially since there was no agreement to that effect. The relationship was, as the High Court initially noted, one whose maintenance was "entrusted solely to the free will of both parties."

- Focus on Legal Obligations, Not Just Emotional Expectations: While the High Court had found Y's conduct in ending the relationship to be "not reasonable" because it "unilaterally betrayed X's expectation of the relationship's continuation," the Supreme Court focused on whether Y had breached any legal duty owed to X or infringed upon any legally protected right or interest of X. Finding none in this specific "partnership" context, it could not affirm tort liability.

- Potential for a "Dual Model" of Protection? The PDF commentary accompanying this case suggests that while the Supreme Court denied relief in this specific instance, its careful wording—"regarding the aforementioned relationship between Y and X..."—might leave open the possibility that other types of non-marital, non-nai'en "partnership relationships" could, under different factual circumstances, involve legally cognizable rights or interests whose infringement might give rise to a claim. This has led to academic discussion about a potential "dual model of relief" where traditional nai'en receives quasi-marital protection, and other intimate relationships might (or might not) find protection under general tort or contract principles depending on their specific attributes and any explicit agreements.

Academic Perspectives and Ongoing Debate

The legal treatment of diverse, non-traditional intimate relationships remains a developing area of law globally and in Japan.

- Arguments for Broader Protection: Some scholars, emphasizing the increasing diversity of lifestyles and family forms, argue for greater legal recognition and protection for various types of committed partnerships that fall outside legal marriage. From this perspective, the High Court's focus on Y's "unreasonable" method of termination and X's betrayed expectations might be seen as a step towards recognizing some level of good faith or fair dealing even in the dissolution of such non-standard relationships. The Supreme Court's rejection of this in X's specific case highlights the high bar for establishing a legally protected interest in the continuation of such a relationship.

- Concerns about Judicial Overreach: Conversely, other scholars express caution about courts too readily imposing legal obligations or recognizing protected interests in purely private, consensual relationships where the parties have explicitly or implicitly chosen to remain outside the legal framework of marriage. They argue that judicial intervention in the termination of such relationships, absent clear agreements or recognized legal statuses like nai'en, could constitute an overreach into personal autonomy and the freedom to form and dissolve relationships.

- Importance of Specific Agreements: This case underscores the importance of clear agreements between parties in non-traditional relationships if they wish to establish specific rights or obligations concerning the relationship's duration or the consequences of its termination. The Supreme Court noted the absence of any agreement that Y could not leave the relationship or marry another.

Conclusion: Autonomy and Risk in Relationships Outside Legal Marriage

The Supreme Court's 2004 decision in this case provides a stark reminder of the legal distinctions between formally registered marriages, recognized de facto marriages (nai'en), and other forms of intimate adult partnerships. Where parties consciously choose to structure their relationship outside the bounds of legal marriage and traditional cohabiting de facto marriage, and do so without specific agreements regarding the continuation or termination of their bond, the Court was unwilling to find a legally protected interest in the relationship's indefinite continuance that would give rise to tort liability for unilateral termination.

The judgment emphasizes that while the emotional impact of ending a long-term, significant relationship can be profound, legal liability for such an ending typically requires the infringement of a recognized legal right or interest. In this particular "partnership relationship," characterized by separate living, financial independence, an explicit disavowal of marital intent after an initial engagement, and no agreement on exclusivity or permanence, the Court found no such legally protectable interest in its continuation that was violated by Y's decision to end it and marry another. The case highlights the legal autonomy afforded to individuals in structuring their personal lives but also the potential lack of legal recourse when such intentionally non-marital relationships are unilaterally ended, absent other specific wrongful conduct.