Beyond "Equality of Arms": How a 1989 Japanese Ruling Refined Self-Defense

Decision Date: November 13, 1989

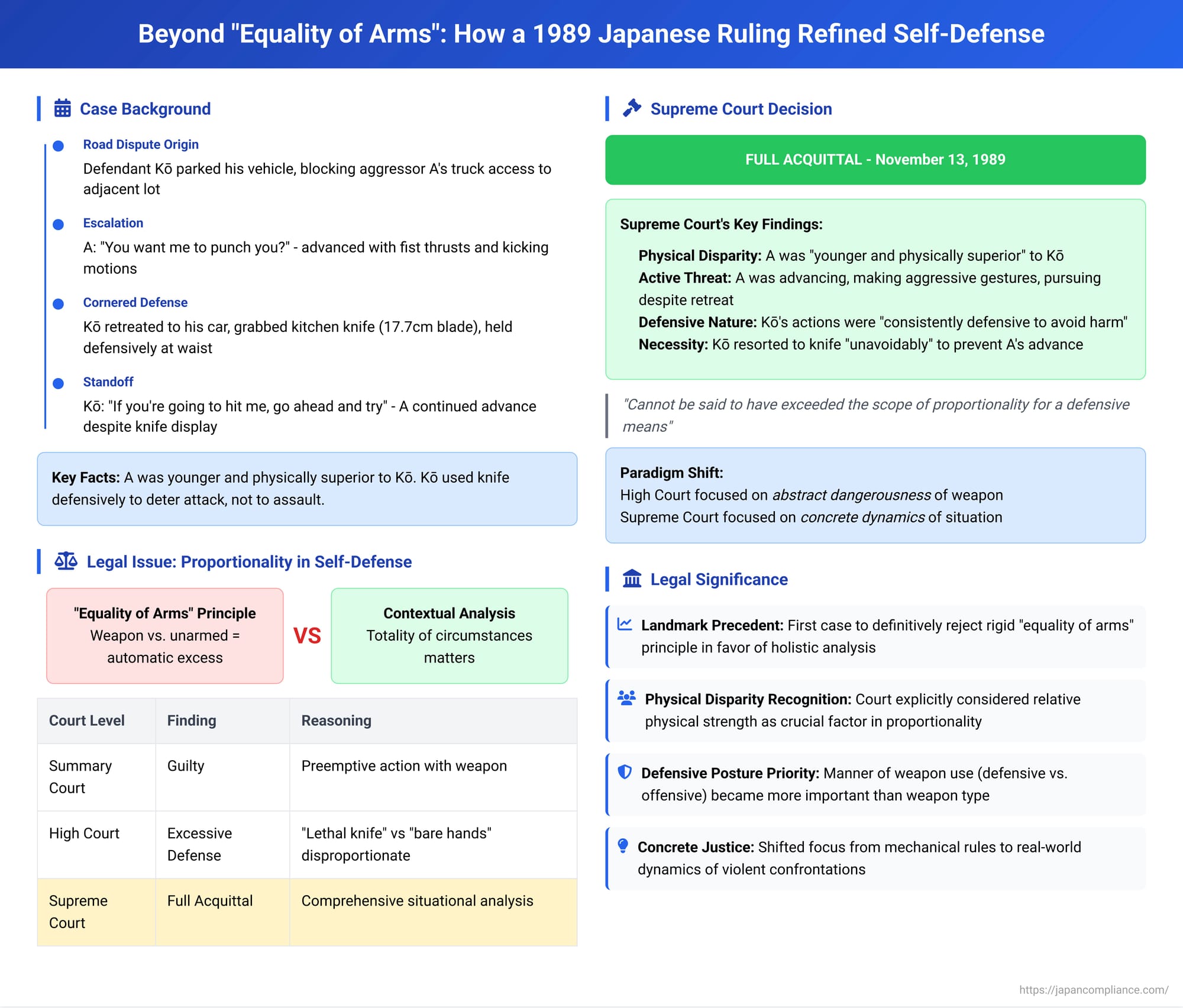

The law of self-defense is built on a simple premise: a person is justified in using force to repel an unlawful attack. Yet, applying this principle is anything but simple. One of the most difficult questions courts face is that of proportionality: How much force is too much? For decades, a kind of informal shorthand often guided this analysis—the "principle of equality of arms," which suggests that meeting a fist with a fist is acceptable, but meeting a fist with a knife is not. This seemingly straightforward rule, however, can lead to unjust outcomes that ignore the realities of a violent confrontation.

On November 13, 1989, the Supreme Court of Japan issued a landmark decision in a case that perfectly illustrated the flaws of this rigid approach. The case involved a roadside dispute where a man, facing an aggressive, physically superior assailant, defended himself with a kitchen knife. In a rare move, the Supreme Court not only overturned the lower court's finding of excessive self-defense but issued a full acquittal, establishing a new, more nuanced, and context-sensitive standard for judging the proportionality of a defensive act.

The Factual Background: A Roadside Confrontation

The incident began with a mundane trigger: a dispute over a parked car. The defendant, Kō, had parked his light cargo vehicle on the road. The aggressor, A, a 39-year-old man, became enraged because Kō's vehicle was making it difficult for him to drive his truck into an adjacent lot. A began shouting at Kō. When Kō told him to "watch your language," A escalated the confrontation.

A advanced on Kō, making overt threats. He shouted, "You want me to punch you?", thrust his fist forward, and made kicking motions as he closed the distance. Kō, feeling scared, began to back away toward his own car, but A pursued him, cornering him at his vehicle.

At that moment, Kō remembered that he had a kitchen knife (a nakiri bōchō with a 17.7 cm blade), which he normally used for peeling fruit, inside his car. Believing he needed to intimidate A to escape harm, he reached into his car, grabbed the knife, and held it in his right hand near his waist. Now armed, Kō faced A, who was about three meters away, and said, "If you're going to hit me, go ahead and try."

Unfazed, A took two or three steps closer, replying, "If you're going to stab me, go ahead and try." Kō then said, "You want to get cut?" For this act of displaying the knife and issuing a verbal threat, Kō was charged with intimidation by displaying a dangerous weapon and with illegally carrying a bladed weapon.

The Lower Courts' Rulings: A Finding of Excessive Defense

The lower courts struggled with how to apply the law of self-defense to these facts.

- The Summary Court: The first-instance court rejected the self-defense claim altogether and found Kō guilty. It reasoned that Kō had taken a "preemptive action" with the knife in response to Kō's own taunt ("go ahead and try"), against an attacker who was, at the end of the day, unarmed.

- The High Court: The appellate court took a more nuanced position. It found that Kō was acting in response to an imminent and unjust attack from A and that he did have the intent to defend himself. However, the High Court concluded that his actions were excessive. It ruled that confronting an attacker who was "merely bare-handed and making punching or kicking motions" with a "lethal vegetable knife" was an act that "exceeded the scope of proportionality for a defensive means." The High Court found him guilty on the basis of excessive self-defense, which still carries a criminal penalty, albeit a potentially reduced one.

Kō appealed this finding of excessiveness to the Supreme Court, arguing that his actions were a fully justified act of self-defense.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Decision: A Full Acquittal

In a decision that marked a significant turning point in Japanese self-defense law, the Supreme Court overturned the High Court's ruling and, in a rare step, issued a full acquittal on its own authority.

The Court agreed with the High Court on two initial points: there was an imminent and unjust attack by A, and Kō acted with the intent to defend himself. The disagreement was squarely on the issue of proportionality. The Supreme Court declared that the High Court had "erred in its interpretation and application" of the statutory requirement that a defensive act must be one "done out of necessity" (yamu o ezu ni shita kōi).

The Court rejected the High Court's simplistic "weapon vs. no weapon" calculus. Instead, it engaged in a holistic and highly context-specific analysis of the situation, highlighting several key facts:

- The Physical Disparity: The Court explicitly noted that the aggressor, A, was "younger and physically superior" to the defendant, Kō. This imbalance of power was a critical part of the context.

- The Nature of the Threat: A was not merely standing still; he was actively advancing, making aggressive gestures, and verbally threatening an assault. He continued to pursue Kō even as Kō was backing away.

- The Defensive Nature of the Act: The Court emphasized that Kō's actions were "consistently defensive in order to avoid harm from A." He did not attack with the knife. He held it at his waist in a defensive posture and used words to try to de-escalate the situation and deter the aggressor. The Court concluded that Kō had resorted to taking the knife "unavoidably" to prevent A's advance and escape harm.

Based on this comprehensive view, the Supreme Court concluded that Kō's actions "cannot be said to have exceeded the scope of proportionality for a defensive means." His act was deemed a justifiable act of self-defense, and he was found not guilty of all charges.

A Deeper Dive: Moving Beyond the "Equality of Arms"

This 1989 decision is celebrated by legal scholars for moving Japanese self-defense law beyond the rigid and often unfair "principle of equality of arms" (buki taitō no gensoku). For years, many lower courts had relied on this informal rule, which tended to find any use of a weapon against an unarmed attacker to be automatically excessive. The High Court's decision in this very case was a classic example of that mechanical thinking.

The Supreme Court's ruling signaled a definitive shift away from this abstract formalism and toward a more concrete, reality-based assessment. The key difference in approach was this:

- The High Court focused on the abstract dangerousness of the weapon. It saw a "lethal knife" versus "bare hands" and concluded the act was excessive.

- The Supreme Court focused on the concrete dynamics of the situation. It saw a physically inferior person, cornered and retreating from a relentless and larger aggressor, using the presence of a weapon not to attack, but to defensively create space and deter an imminent assault.

This holistic analysis gives true meaning to the statutory requirement that a defensive act be "done out of necessity." The necessity of an action cannot be judged in a vacuum; it depends entirely on the specific circumstances faced by the defender at that moment. The Supreme Court's careful consideration of the physical disparity between the two men, the aggressor's persistent advance, and the defender's purely defensive posture were all crucial to finding that his actions were, in fact, necessary and appropriate.

Conclusion: From Mechanical Rules to Concrete Justice

The 1989 Supreme Court decision is a landmark ruling that fundamentally reshaped the understanding of proportionality in Japanese self-defense law. It powerfully rejected the simplistic "equality of arms" principle, instructing courts to instead conduct a nuanced and comprehensive evaluation of the totality of the circumstances. The ruling established that using a weapon against an unarmed attacker is not automatically excessive. The legality of the defensive act depends on a concrete assessment of factors like the relative physical strength of the parties, the nature and persistence of the threat, and the manner in which the defensive tool was actually used. By acquitting the defendant, the Supreme Court sent a clear message that the law of self-defense must be flexible enough to account for the real-world dynamics of violent confrontations, prioritizing concrete justice over adherence to a rigid, mechanical rule.