Beyond Direct Employment: Prime Contractor's Safety Duty to Subcontractor's Workers – The Subcontractor S / Prime Contractor P Construction Site Case (December 18, 1980)

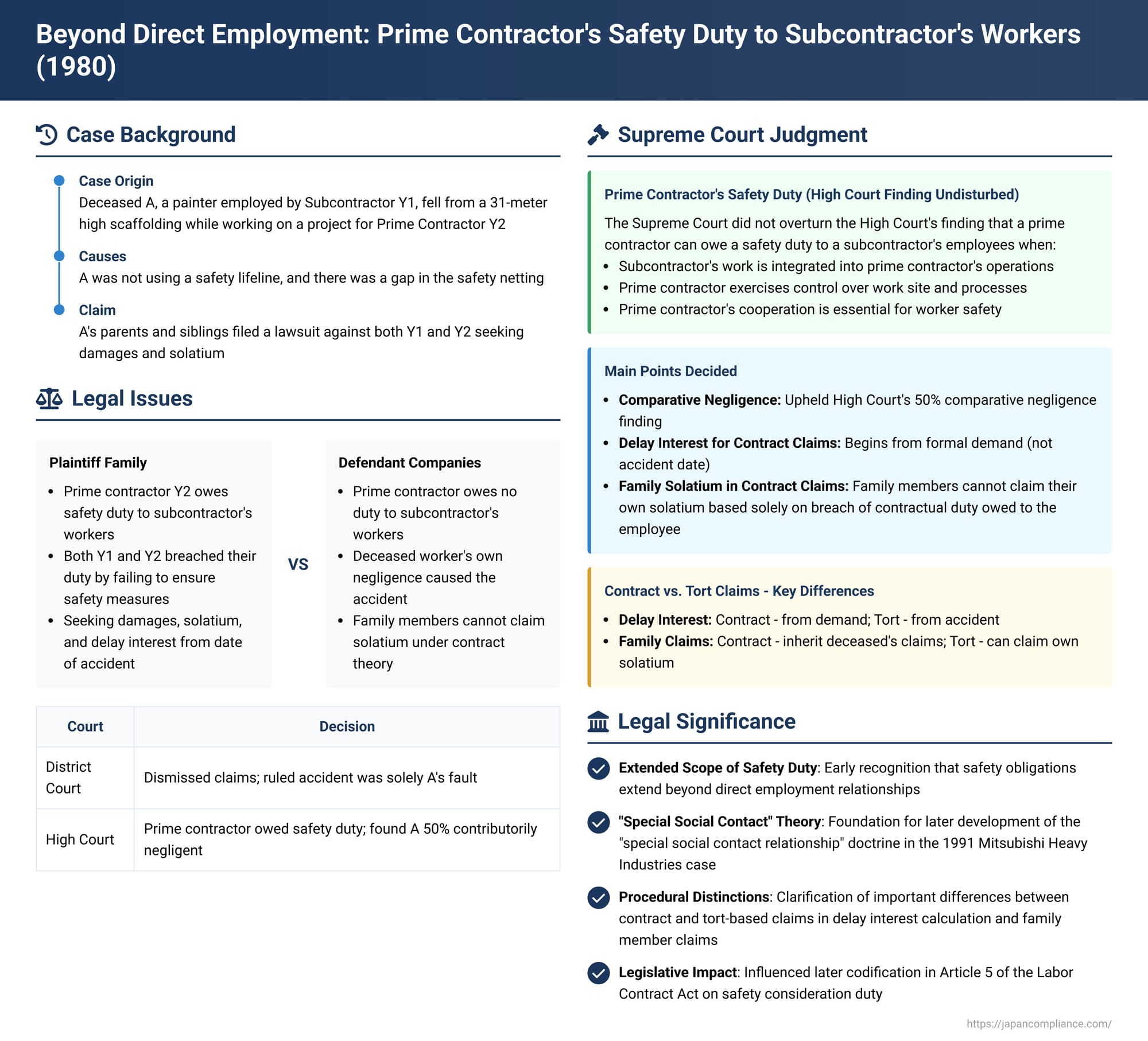

On December 18, 1980, the First Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan delivered a judgment in a damages claim case. While the Supreme Court's primary focus in this appeal was on aspects of comparative negligence and the calculation of damages, the case stands as a significant early marker in the evolving jurisprudence concerning the safety obligations of prime contractors towards the employees of their subcontractors on construction sites and other multi-layered work environments.

A Tragic Fall and the Question of Responsibility

The case arose from a fatal accident involving Deceased A, a painter employed by Company Y1 (the subcontractor). Company Y1 had been subcontracted by Company Y2 (the prime contractor) to perform steel frame painting work as part of a larger converter plant construction project that Company Y2 had undertaken for a client, Company B.

While working on this project, Deceased A was engaged in painting activities on scaffolding situated 31 meters above the ground. Tragically, A fell from this height and died. Investigations revealed that at the time of the accident, A was not using a safety lifeline, and there was a gap present in the safety netting (養生網 - yōjōmō), which contributed to the fall.

Following A's death, A's parents (Plaintiffs X1 and X2) and younger siblings (Plaintiffs X3-X7) filed a lawsuit against both Company Y1 (A's direct employer) and Company Y2 (the prime contractor). They sought compensation for damages, including A's lost future earnings (calculated at 7,781,901 yen), solatium for the parents (1.25 million yen each) and siblings (300,000 yen each), and delay interest on these amounts accruing from the day after the accident. The claims were based on an alleged breach of a "safety assurance duty" (安全保証義務 - anzen hoshō gimu, considered synonymous with the more commonly termed "safety consideration duty," 安全配慮義務 - anzen hairyō gimu) under the employment contract, as well as on tort law.

The Lower Courts' Journey: Defining the Scope of Safety Duties

- First Instance (Fukuoka District Court, Kokura Branch): The trial court acknowledged that Company Y1, as the direct employer, owed a contractual safety duty to Deceased A. It also recognized that Company Y2, the prime contractor, owed a similar safety duty to A arising from the subcontracting agreement with Company Y1. However, the court ultimately dismissed the plaintiffs' claims. It inferred that Deceased A, despite having received safety training, had personally detached the safety lifeline and opened the safety netting, possibly to receive paint supplies, and concluded that A's death was solely attributable to A's own negligence. Consequently, it denied any breach of safety duty or tort liability on the part of either Company Y1 or Company Y2.

- Appeal (Fukuoka High Court): The High Court took a significantly different stance, particularly regarding the prime contractor's responsibility.

- Prime Contractor's Duty of Care: The High Court established that a prime contractor could indeed owe a duty of care, equivalent in content to an employer's contractual safety duty, to a subcontractor's employee, even in the absence of a direct employment contract between them. It laid out several conditions for such a duty to arise:

- The subcontractor's employee, despite formal employment only with the subcontractor, effectively receives the work location, equipment, and tools from the prime contractor.

- The worker is subject to the direct command and supervision of the prime contractor.

- The subcontractor's operation is organizationally and practically integrated to such an extent that it functions like a department of the prime contractor.

- Both the prime contractor and the subcontractor jointly manage safety at the worksite.

- The prime contractor's cooperation, direction, and supervision are indispensable for ensuring the safety of the subcontractor's employees.

- An economic and social relationship exists between the prime contractor and the subcontractor's worker that is comparable to a direct employer-employee relationship.

- Application to Company Y2: Applying these criteria, the High Court found that Company Y2 managed the overall progress of Company Y1's subcontracted work, was fully aware of the project's status, and was in a position to issue instructions and commands regarding both the work itself and safety measures. Therefore, the High Court affirmed that Company Y2 owed a safety duty to Deceased A.

- Breach of Duty and Comparative Negligence: The High Court concluded that both Company Y1 and Company Y2 had breached their respective safety duties. For instance, they could have taken measures to prevent the unauthorized opening of safety nets, and it could not be definitively established that Deceased A was the one who had opened the netting. However, the High Court also found Deceased A to be 50% contributorily negligent. Its reasoning was that, even if there was an opening in the safety net, an experienced painter like A, exercising ordinary caution, would not typically fall from such a height.

The High Court thus awarded damages but reduced them by 50% due to A's comparative negligence.

- Prime Contractor's Duty of Care: The High Court established that a prime contractor could indeed owe a duty of care, equivalent in content to an employer's contractual safety duty, to a subcontractor's employee, even in the absence of a direct employment contract between them. It laid out several conditions for such a duty to arise:

A's parents (Plaintiffs X1 and X2) appealed this High Court decision to the Supreme Court, specifically challenging the 50% finding of comparative negligence, the principles applied to the commencement date for delay interest, and issues surrounding their own claims for solatium.

The Supreme Court's Adjudication: Focus on Damages and Procedural Aspects

The Supreme Court partially dismissed the appeal and partially quashed and self-adjudicated certain aspects. The prime contractor's (Company Y2's) fundamental duty of care towards the subcontractor's employee (Deceased A), as established by the High Court, was not a direct point of contention in this final appeal and thus was not overturned by the Supreme Court. The Supreme Court's judgment primarily focused on:

- Comparative Negligence: The Supreme Court upheld the High Court's finding that Deceased A was at least 50% at fault for the occurrence of the damages. The Court deemed this assessment by the High Court to be justifiable and found no error in it.

- Delay Interest for Breach of Contractual Duty: The Supreme Court clarified the starting point for delay interest when damages arise from a breach of a contractual (or quasi-contractual) safety duty. It stated: "A damage compensation obligation arising from a breach of contract is an obligation for which no due date is fixed. According to Article 412, Paragraph 3 of the Civil Code, the obligor falls into delay only when they receive a demand for performance from the obligee".

- The Court determined that the plaintiffs' successful claim (as upheld by the High Court, albeit reduced) was based on the breach of the "safety assurance duty"—a contractual or quasi-contractual obligation—rather than on tort.

- In this case, the formal demand for performance regarding this contractual breach claim was made when the plaintiffs' legal counsel submitted a preparatory document to the court asserting this specific claim on November 26, Showa 48 (1973).

- Therefore, the Supreme Court ruled that delay interest should accrue from the day after this demand, i.e., November 27, 1973, and not from the day immediately following the accident as would be typical in a tort claim. The High Court had only awarded delay interest from a later date (January 21, Showa 51, or 1976) and had incorrectly failed to award it for the period between November 27, 1973, and January 20, 1976, on the principal sum it had determined was due after the 50% reduction. The Supreme Court recalculated this specific portion of delay interest and ordered its payment.

- Solatium for Family Members (Parents) in Contractual Breach Claims: The Supreme Court addressed the parents' claim for their own, distinct solatium due to the emotional suffering caused by A's death. It stated: "It is difficult to construe that the surviving family members X1 and X2 acquire a right to claim their own solatium due to a breach of obligations under an employment contract or a legal relationship equivalent thereto".

- This means that while the parents, as heirs, could inherit Deceased A's own claim for damages (including A's own pain and suffering before death and lost future earnings), they could not lodge a separate, personal claim for their own emotional distress based solely on the breach of the contractual safety duty owed by Company Y1 or Company Y2 to Deceased A. The High Court had awarded some solatium to the parents; the Supreme Court found the amount ultimately justifiable but clarified that the legal basis for such an award to family members themselves does not directly stem from the contractual breach owed to the employee. (Such independent claims by family members for their own suffering are more typically recognized under tort law, e.g., Civil Code Article 711).

Unpacking the Prime Contractor's Safety Duty of Care

Although the existence of Company Y2's (the prime contractor's) safety duty towards Deceased A was not the central point of dispute before the Supreme Court in this particular appeal, the High Court's detailed reasoning for recognizing such a duty was left undisturbed and reflects an important stream of judicial thought.

- The "Special Social Contact Relationship": The legal basis for extending a safety duty of care to non-direct employees, like a subcontractor's worker, was more explicitly articulated by the Supreme Court in a later key case, the Mitsubishi Heavy Industries Kobe Shipyard Case (judgment of April 11, 1991). In that case, the Court held that if a subcontractor's employee works at the prime contractor's premises, uses the prime contractor's facilities and tools, is de facto under the prime contractor's command and supervision, and performs work virtually identical to that of the prime contractor's own direct employees, a "special social contact relationship" (特別な社会的接触の関係 - tokubetsu na shakaiteki sesshoku no kankei) is formed. This relationship, based on the principle of good faith, imposes a safety consideration duty on the prime contractor towards the subcontractor's employee. The conditions laid out by the Fukuoka High Court in the Oishi/Kajima case align closely with this concept. This "special social contact relationship theory" has become the dominant view in subsequent case law and among legal scholars.

- Statutory Codification: Today, Article 5 of Japan's Labor Contract Act explicitly codifies the employer's safety consideration duty as an inherent obligation arising from the employment contract. For complex work relationships involving multiple tiers of contractors, an analogous application of this statutory provision is generally considered appropriate to determine the safety duties of parties like prime contractors who exercise significant control over the work environment and processes.

- Comparing Legal Bases for Claims (Tort vs. Contract):

- Historically, tort law was the primary basis for seeking damages in industrial accidents. However, influenced by developments in medical malpractice litigation, claims based on breach of a contractual safety duty of care became more prevalent, a trend solidified by the Supreme Court in cases like the Self-Defense Forces Hachinohe Vehicle Maintenance Plant Case (judgment of February 25, 1975).

- While there was some debate about whether a contractual claim offered advantages over a tort claim (e.g., in terms of burden of proof or the scope of duty), most significant differences have diminished over time. For instance, amendments to the Civil Code (effective April 1, 2020) have largely harmonized the statute of limitations for tort claims with those for contract claims (generally 5 years from knowledge of the damage and tortfeasor).

- However, as this Oishi/Kajima judgment clearly demonstrates, distinctions remain critical in areas like:

- Accrual of Delay Interest: For contractual breaches, interest starts from the day after a formal demand for payment by the creditor. For torts, it typically starts from the date of the tortious act (e.g., the accident date).

- Family Members' Independent Solatium Claims: Such claims are generally not recognized under a breach of contract theory (where the contract is with the deceased employee) but can be pursued under tort law.

Conclusion: Expanding the Net of Safety Responsibility

The Oishi Painting/Kajima Construction case, particularly through the High Court's reasoning which the Supreme Court did not disturb on this point, was an early and important step in recognizing that prime contractors can bear a direct safety responsibility for the well-being of their subcontractors' employees under conditions of significant integration and control. While the Supreme Court's specific rulings in this appeal focused on refining the calculation of damages and the distinct consequences of pursuing claims under contract versus tort theories, the case as a whole contributed to the broader legal understanding that safety duties can extend beyond the confines of direct employment contracts. It underscores the principle that parties exercising substantial control over a worksite and work processes may also carry a corresponding duty to ensure the safety of all workers present, a concept further developed in subsequent jurisprudence and now partially reflected in statutory law.