Beyond Design Patents: Protecting Product Shapes in Japan via Copyright and Unfair Competition Law

TL;DR

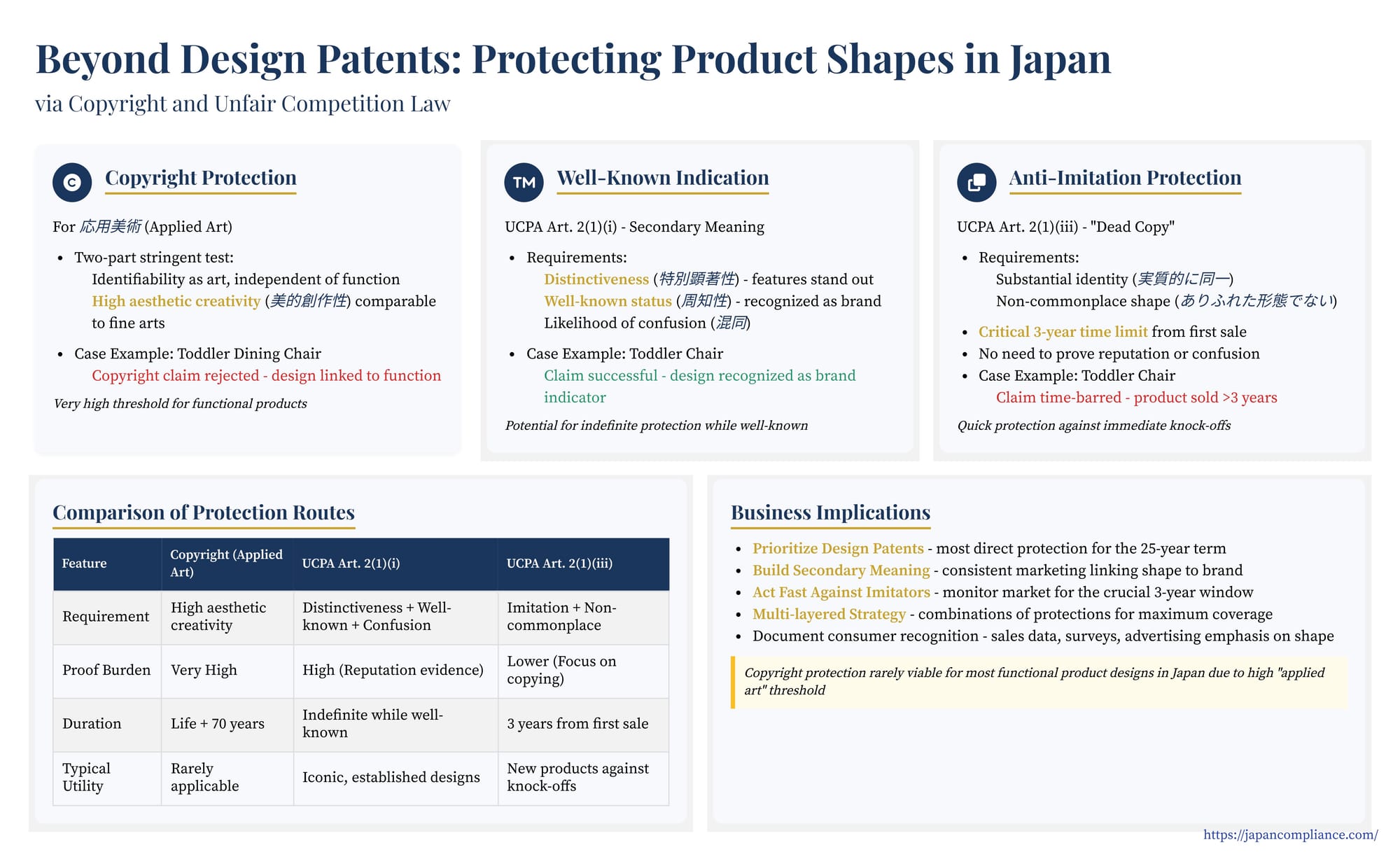

- After a design patent expires—or was never filed—Japan offers two fallback routes: (i) rare “applied-art” copyright and (ii) unfair-competition claims (well-known trade dress or anti-dead-copy).

- Copyright demands a high level of artistic creativity separable from function; very few industrial designs qualify.

- The toddler-chair IPHC decision shows UCPA Article 2(1)(i) (well-known indication) can succeed if the shape has gained source-identifying fame; Article 2(1)(iii) can stop dead copies but only within 3 years of launch.

- Businesses should combine design patents with branding that ties distinctive, non-functional shapes to the company before imitations appear.

Table of Contents

- Copyright Protection for Product Designs: The High Bar of “Applied Art”

- Unfair Competition Prevention Act (UCPA): Alternative Routes

- Comparing the Protection Routes

- Implications for Businesses

- Conclusion

Securing intellectual property rights for innovative product designs is crucial for maintaining a competitive edge. In Japan, design patents (意匠権, ishōken) under the Design Act offer the primary route for protecting the novel aesthetic appearance of industrial products for a fixed term (currently 25 years from filing). However, what happens when design patent protection expires, or wasn't obtained? Can the distinctive shape or configuration of a product still be protected? Japan's Copyright Act (著作権法, Chosakuken-hō) and Unfair Competition Prevention Act (不正競争防止法, Fusei Kyōsō Bōshi Hō - UCPA) offer potential alternative avenues, but each comes with specific requirements and limitations, as illustrated by a recent high-profile case involving a well-known children's chair.

Copyright Protection for Product Designs: The High Bar of "Applied Art"

Japan's Copyright Act primarily protects creative works like literature, music, and fine arts. Industrial designs, being functional articles, generally fall outside its scope to avoid granting excessively long monopolies (life of the author plus 70 years) on potentially useful shapes.

However, a narrow exception exists for "works of applied art" (応用美術, ōyō bijutsu). A functional product's design can receive copyright protection if it meets a stringent, two-part test established by Japanese courts:

- Identifiability as Art: It must possess aesthetic features capable of being appreciated as art independently.

- High Artistic Level/Aesthetic Creativity: These aesthetic features must reach a high level of artistic expression or "aesthetic creativity" (美的創作性, biteki sōsakusei) comparable to that found in fine arts (e.g., painting, sculpture).

Crucially, the aesthetic creativity must be separable from the product's function. If the design choices, however unique or attractive, are primarily dictated by functional requirements or efficiency, copyright protection is generally denied. Merely being a novel or pleasing design for a useful object is insufficient.

Case Example: The Toddler Dining Chair

The challenge of meeting this standard was highlighted in a recent Intellectual Property High Court decision (May 31, 2023, Reiwa 4 (Ne) 10075). The case involved a highly recognizable and commercially successful toddler dining chair known for its distinctive features, including A-shaped side frames enabling adjustable seat and footrest plates within an L-shaped overall structure.

The plaintiff argued the chair's design qualified as a work of applied art deserving copyright protection. The IP High Court, however, rejected this claim. While acknowledging the chair's distinctive appearance and market success, the court found its core design elements were intrinsically linked to its functions: stability, adjustability to a growing child, and providing safe support. The court concluded that the design did not exhibit the high degree of purely aesthetic creativity, separable from function, required to elevate it to the level of a copyrighted work of applied art under Japanese law. It viewed the design as an excellent functional solution rather than primarily an artistic expression.

This ruling reaffirms the extremely high threshold for copyright protection for industrial designs in Japan.

Unfair Competition Prevention Act (UCPA): Alternative Routes

While copyright proved unavailable in the chair case, the UCPA offered alternative grounds for protection, focusing on preventing unfair market practices rather than rewarding artistic creativity. The UCPA provides several relevant avenues:

1. Protection as a Well-Known Indication of Source (UCPA Art. 2(1)(i))

- Concept: This provision prohibits acts causing confusion with another's goods or business by using an "indication of goods or business" (shōhin tō hyōji) that is well-known (shūchi, 周知) among consumers or traders. While often applying to names or logos, a product's distinctive configuration (shōhin keitai, 商品形態) can qualify as a shōhin tō hyōji if it has acquired secondary meaning – meaning consumers recognize the shape itself as identifying the source (brand) of the product. This is akin to trade dress protection.

- Requirements: To succeed under this provision, the plaintiff must prove:

- Distinctiveness (Tokubetsu Kenchosei, 特別顕著性): The configuration possesses features that objectively make it stand out from functionally similar products. Purely functional features cannot serve as source indicators.

- Well-Known Status (Shūchisei, 周知性): The configuration has become widely recognized among the relevant consuming public or trade circles as indicating the plaintiff's specific brand. Evidence like long-term exclusive use, extensive advertising highlighting the shape, high sales figures, media coverage, and consumer surveys are typically required.

- Likelihood of Confusion (Kondō, 混同): The defendant's use of a similar configuration is likely to cause consumers to mistakenly believe the defendant's product originates from, is associated with, or is sponsored by the plaintiff.

- Case Example (Toddler Chair): In contrast to the copyright claim, the plaintiff succeeded under this provision. The IP High Court found that the chair's specific combination of features (A-shaped frames, overall structure, adjustable plates) was indeed distinctive and, based on extensive evidence of long market presence (decades), widespread advertising, numerous awards, and consumer recognition, had achieved well-known status as an indicator of the plaintiff's brand. The court concluded that the defendant's similar chair created a likelihood of consumer confusion regarding the source. This allowed the court to grant an injunction against the defendant's sales based on UCPA Art. 2(1)(i).

2. Protection Against Imitation of Product Configuration (UCPA Art. 2(1)(iii))

- Concept: This provision specifically targets the act of selling, importing, or manufacturing products that imitate (mohō, 模倣) the configuration of another party's product (essentially, creating a "dead copy"). It aims to prevent free-riding on the design efforts invested by the original creator.

- Requirements:

- Substantial Identity: The defendant's product configuration must be substantially identical ("dead copy" - 実質的に同一, jisshitsuteki ni dōitsu) to the plaintiff's product configuration. Minor differences are ignored if the overall impression is one of imitation.

- Originality (Non-Commonplace): The plaintiff's configuration must not be commonplace (arifureta keitai, ありふれた形態) in Japan at the time it was created. Purely functional shapes dictated solely by technical necessity are also excluded.

- No Need for Reputation/Confusion: Unlike Art. 2(1)(i), this claim does not require proof that the plaintiff's configuration is well-known or that there is a likelihood of consumer confusion. It focuses solely on the act of copying a non-commonplace design.

- Crucial Time Limit: Protection under Art. 2(1)(iii) is strictly limited to three years from the date the plaintiff's product incorporating the configuration was first sold in Japan (UCPA Art. 19(1)(v)(a)).

- Case Example (Toddler Chair): The court factually determined that the defendant's chair did imitate the plaintiff's configuration under the definition in Art. 2(1)(iii). However, because the plaintiff's chair had been sold in Japan for far longer than three years, the claim based on this specific provision was time-barred by the statute of limitations and therefore dismissed, despite the finding of imitation.

Comparing the Protection Routes

| Feature | Copyright (Applied Art) | UCPA Art. 2(1)(i) (Well-Known Indication) | UCPA Art. 2(1)(iii) (Imitation) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Requirement | High aesthetic creativity, separable from function | Distinctiveness + Well-Known Status (Source ID) + Likelihood of Confusion | Substantial Imitation + Non-Commonplace Shape |

| Proof Burden | Very High Standard | High (Requires evidence of reputation) | Lower (Focus on copying, not reputation) |

| Duration | Life of author + 70 years | Potentially indefinite (while well-known) | 3 years from first sale in Japan |

| Typical Utility | Rarely applicable to functional products | Established, iconic designs | New product designs against immediate knock-offs |

Implications for Businesses

- Prioritize Design Patents: For novel industrial designs, obtaining a Japanese design patent remains the most direct and reliable form of protection for its term.

- Build Secondary Meaning for Long-Term Protection: If aiming for protection beyond the design patent term (or if a patent wasn't secured), focus on building strong consumer recognition linking the product's distinctive, non-functional visual elements to your brand. This requires consistent marketing, promotion highlighting the shape, and potentially gathering evidence like sales data and consumer surveys for a potential UCPA claim under Art. 2(1)(i).

- Act Fast Against Imitators: The strict three-year time limit under UCPA Art. 2(1)(iii) necessitates swift action. Monitor the market closely after launching new products in Japan and be prepared to act quickly against direct copies.

- Copyright is Unlikely for Functional Designs: While not impossible, relying on copyright law to protect the shape of most functional products in Japan is a high-risk strategy due to the demanding "applied art" standard.

Conclusion

Protecting the unique shape or configuration of a product in Japan offers multiple legal avenues, each with distinct requirements and limitations. While copyright protection is rarely granted for functional items, the Unfair Competition Prevention Act provides viable alternatives. Establishing a product shape as a well-known source identifier (UCPA Art. 2(1)(i)) can offer robust, long-term protection against confusingly similar products, as demonstrated in the toddler chair case, but requires significant investment in building brand recognition tied to the shape. For newer designs, the anti-imitation provision (UCPA Art. 2(1)(iii)) offers a valuable, albeit time-limited, tool against direct knock-offs. Businesses seeking comprehensive protection for their product designs in Japan should employ a strategic approach, prioritizing design patents while actively building brand association with unique configurations and being prepared to enforce their rights swiftly under the UCPA when necessary.

- Protecting Product Configuration in Japan: Using the UCPA to Safeguard Trade Dress

- False IP Takedowns on Japanese E-Commerce Platforms: UCPA Liability & Risk-Control Guide

- Who Owns AI-Generated Works in Japan? Copyright, Authorship & Article 2 Criteria Explained

- JPO Design & Trade-Dress Examination Guidelines (Japanese PDF)