Beyond Day-to-Day Business: Court-Appointed Agents and Shareholder Meetings in Japan

Case: Action for Cancellation of a Shareholders' Meeting Resolution

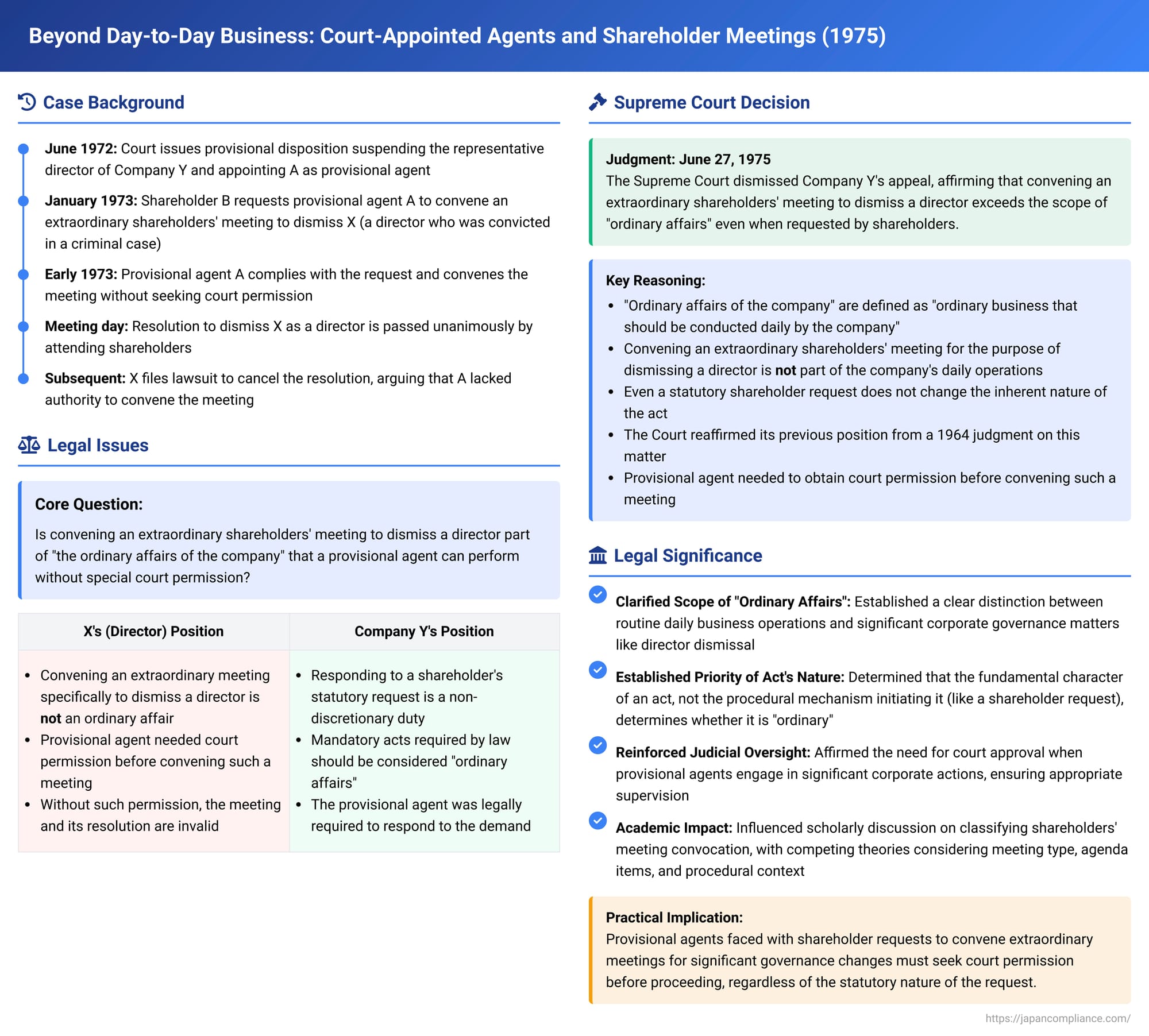

Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench, Judgment of June 27, 1975

Case Number: (O) No. 157 of 1975

When a company's representative director is suspended from their duties due to internal disputes and ongoing litigation, a court may appoint a provisional agent (shokumu daikōsha) to step in and manage the company's affairs. This agent, however, typically operates under a critical restriction: without specific court permission, their authority is limited to the "ordinary affairs of the company" (kaisha no jōmu). A pivotal Supreme Court decision on June 27, 1975, delved into what constitutes "ordinary affairs," particularly when the agent is asked to convene an extraordinary shareholders' meeting for the weighty purpose of dismissing a director, even if such a meeting is requested by shareholders exercising their statutory rights.

Conflict, Conviction, and Convocation: Facts of the Case

The case involved Company Y, a taxi business experiencing internal strife among its officers. This conflict led to a court issuing a provisional disposition in June 1972 under the then-Commercial Code (Article 270, Paragraph 1). This order suspended the duties of Company Y's incumbent representative director and appointed an individual, A, as the provisional agent tasked with performing the representative director's functions.

Further complicating matters, X, who was both a shareholder and a director of Company Y, was convicted in a criminal case. Following this conviction, in January 1973, another shareholder of Company Y, B, formally requested the provisional agent A to convene an extraordinary shareholders' meeting. The specific agenda for this proposed meeting was the dismissal of X from his position as a director of Company Y. This request was made pursuant to a provision in the then-Commercial Code (Article 237, similar to Article 297 of the current Companies Act) that allowed shareholders to demand the convocation of a meeting.

Provisional agent A complied with shareholder B's request. A issued convocation notices to all of Company Y's shareholders for an extraordinary shareholders' meeting, which was subsequently held. At this meeting, a resolution to dismiss X as a director was passed with the unanimous consent of all shareholders present.

The Legal Challenge: The Agent's Authority and "Ordinary Affairs"

X challenged his dismissal by filing a lawsuit to cancel the shareholders' meeting resolution. His core argument was that the act of convening an extraordinary shareholders' meeting, especially one for the purpose of dismissing a director, fell outside the scope of "the ordinary affairs of the company". This phrase was used in the then-Commercial Code Article 271, Paragraph 1 (a provision substantially similar to Article 352, Paragraph 1 of the current Companies Act), which limited a provisional agent's authority to such ordinary affairs unless they obtained court permission for acts beyond that scope.

X contended that since provisional agent A had not sought or obtained the necessary court permission to convene this extraordinary meeting for director dismissal, the convocation procedure itself was illegal. This illegality, X argued, rendered the subsequent dismissal resolution voidable and liable to be cancelled.

Both the court of first instance and the appellate court agreed with X's arguments and ruled in his favor, ordering the cancellation of the dismissal resolution.

The Company's Defense: A Non-Discretionary Duty?

Company Y appealed to the Supreme Court. Its main argument was that the distinction between "ordinary" and "non-ordinary" affairs should hinge on whether the act in question is mandated by law or the company's articles of incorporation. Company Y asserted that when minority shareholders exercise their statutory right to demand the convocation of an extraordinary shareholders' meeting, the representative director (or, by extension, a provisional agent acting in that capacity) is generally obligated to convene the meeting. There is little to no room for discretion in such a scenario.

Therefore, Company Y argued, the act of convening the meeting in response to shareholder B's request should be considered an "ordinary affair," even if its purpose was the dismissal of a director. Consequently, no special court permission should have been required for A to call the meeting.

The Supreme Court's Stance: Dismissal is Not "Ordinary Business"

The Supreme Court dismissed Company Y's appeal, thereby upholding the lower courts' decisions in favor of X.

Reasoning of the Apex Court: Nature of the Act Prevails

The Supreme Court's reasoning was clear and grounded in its prior jurisprudence:

- The Court explicitly reaffirmed its stance from a previous case (a Supreme Court, First Petty Bench judgment of May 21, 1964, concerning a limited company), stating that convening an extraordinary shareholders' meeting for the specific purpose of dismissing a director is to be considered an act "not belonging to the ordinary affairs of the company" (会社ノ常務ニ属セザル行為).

- This principle holds true even when the convocation of such an extraordinary meeting is based on a request from minority shareholders exercising their statutory rights.

- The Court defined "ordinary affairs of the company" (kaisha no jōmu) as "ordinary business that should be conducted daily by the said company". It found that convening an extraordinary meeting specifically to dismiss a director does not fit this description of daily, usual business operations.

- Crucially, the Court stated that the inherent nature of the act of convocation itself (i.e., calling an EGM for director dismissal) is not altered merely because it was initiated by a minority shareholder's request. It remains an act outside the company's everyday, ordinary course of business.

Therefore, because provisional agent A had convened the meeting for a non-ordinary purpose without obtaining the requisite court permission, the convocation was flawed, and the resolution dismissing X was rightly cancelled.

Analysis and Implications: Defining the Boundaries of Agent Authority

This 1975 Supreme Court judgment is a significant interpretation of the powers of court-appointed provisional agents, particularly representative director's provisional agents, and it continues to hold relevance under the current Companies Act.

- Role and Powers of a Director's Provisional Agent (shokumu daikōsha):

When a director's (especially a representative director's) ability to perform their duties is compromised due to ongoing legal disputes (such as lawsuits challenging their appointment or seeking their dismissal), a court can appoint a provisional agent. This is a provisional remedy, now primarily governed by Article 23, Paragraph 2 of the Civil Provisional Remedies Act, designed to ensure the company can continue to function while its leadership is in question.

The agent's powers are explicitly limited by statute (now Companies Act Article 352, Paragraph 1, which is substantively similar to the former Commercial Code Article 271 cited in the case). Unless the court order appointing them states otherwise, or unless they subsequently obtain specific court permission, they are restricted to acts within "the ordinary affairs of the company". - Defining "Ordinary Affairs of the Company":

The Supreme Court's definition in this case – "ordinary business that should be conducted daily by the said company" – aligns with the general understanding that the provisional agent's role is primarily that of a caretaker. Their main task is to maintain the company's operational status quo and preserve its assets until the underlying legal dispute concerning the directorship is resolved.

There is broad academic consensus that routine operational activities, such as purchasing necessary raw materials or selling finished products in line with the company's usual business, fall under "ordinary affairs". Conversely, significant, transformative actions like issuing new shares, major business transfers, or amending the articles of incorporation are generally considered non-ordinary and would require court permission for an agent to undertake. - Is Convening a Shareholders' Meeting an "Ordinary Affair"?

This specific question has been a subject of considerable academic discussion, with various viewpoints emerging:The 1975 Supreme Court judgment, by emphasizing both the "extraordinary" nature of the meeting and its specific purpose of "director dismissal," appears to align most closely with either view (a) or a version of view (d) where a non-routine and significant agenda item like director dismissal renders the convocation itself non-ordinary.- (a) Distinction between Meeting Types: Some argue that convening regular or annual general meetings (which handle routine matters like approving annual accounts) might be considered ordinary, but convening extraordinary general meetings (EGMs), especially for contentious issues, is not. The Supreme Court's 1964 decision, referenced in the 1975 judgment, which found that convening an EGM in a limited company was not an ordinary affair, lends support to this view.

- (b) Convening vs. Executing: Another view suggested that the act of convening any meeting might always be ordinary, but the agent would need permission to execute any resolutions passed if the subject matter of those resolutions was non-ordinary. This view has been criticized as impractical, as it diminishes the purpose of convening the meeting if its outcomes cannot be implemented.

- (c) Always Non-Ordinary: A stricter view posits that convening any shareholders' meeting is always a non-ordinary affair, primarily because the decision to convene a meeting (in a company with a board) is a statutory power of the board of directors, involving deliberation and decision-making that goes beyond mere routine administration.

- (d) Agenda-Dependent: A more nuanced approach suggests that whether convening a meeting is ordinary depends on the agenda of that meeting. If the proposed agenda items themselves fall within the company's ordinary affairs, then convening the meeting for such purposes might also be considered ordinary.

- Impact of a Minority Shareholder's Request:

Company Y's argument that the shareholder request transformed the agent's act into a non-discretionary, and therefore ordinary, duty was a key point. Under the Companies Act (Article 297), shareholders meeting certain criteria can demand that the directors convene a shareholders' meeting. If the directors fail to do so, the shareholders can seek court permission to convene the meeting themselves.

The Supreme Court, however, found this argument unpersuasive. It held that even if a shareholder request creates an obligation for the representative director (or the agent) to act, it does not change the fundamental nature of the act of convening an EGM for director dismissal. The process of convocation, even if initiated by shareholders, still notionally involves consideration by the company's decision-making bodies (for which the agent acts) and is not merely a mechanical response. For instance, the board (or the agent acting in that capacity) might need to prepare reference documents for the shareholders' meeting, including its own opinion or reasons for a proposal, which implies a level of deliberation beyond routine tasks. - Practical Steps for the Provisional Agent:

Given this ruling, a representative director's provisional agent faced with a shareholder request to convene an EGM for a non-ordinary purpose like director dismissal must seek court permission. This permission would likely be required not only for the act of sending out convocation notices but also for any necessary preceding steps, such as participating in (or making on behalf of the board) the formal decision to convene the meeting with such an agenda.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's June 27, 1975, decision provides a clear and enduring principle: convening an extraordinary shareholders' meeting for the significant purpose of dismissing a director is not considered part of "the ordinary affairs of the company." Consequently, a representative director's provisional agent must obtain court permission before undertaking such an action, even if the meeting is requested by minority shareholders exercising their statutory rights. This ruling reinforces the understanding that provisional agents are primarily caretakers appointed to manage a company's routine operations during a period of leadership uncertainty. Actions that could fundamentally alter the company's governance structure or resolve contentious internal disputes, such as dismissing a director, fall outside this everyday scope and require judicial oversight to ensure they are handled appropriately and within the bounds of the agent's limited authority.